Picture a course that would double as a home for the finest women golfers in the world, a state-of-the-art facility that would be to the LPGA Tour what TPC Sawgrass is to the PGA Tour.

Like Sawgrass, it would be open to the public for a high-end fee. It would also host a marquee annual event, a Players Championship, of sorts, that would showcase the talents of top female players in ways never seen before, because, for the first time, every inch of the grounds would be designed specifically with their games in mind.

Sound good?

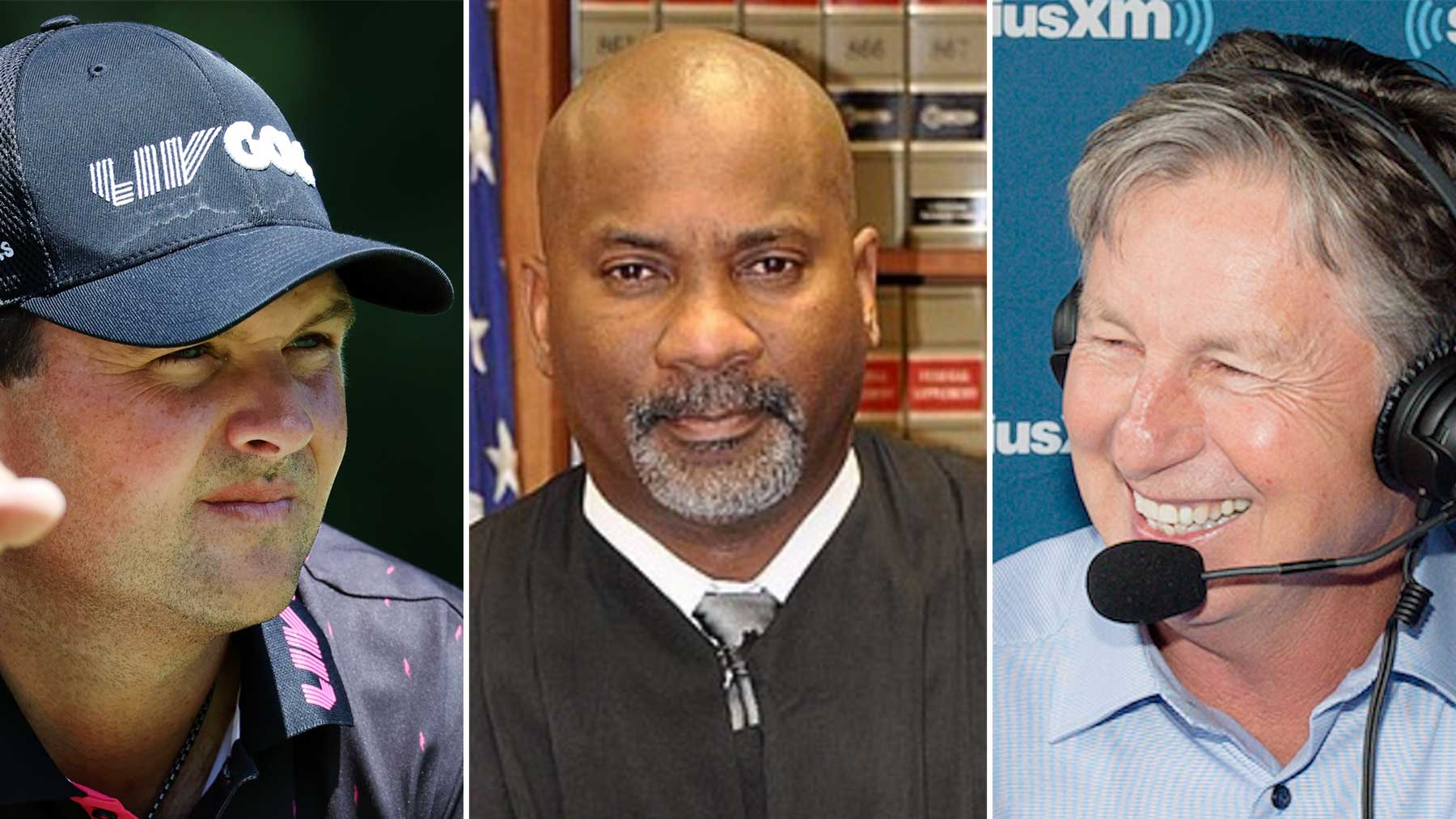

It does to Brandel Chamblee.

So much so, the Tour pro-turned broadcaster-turned-course architect tells GOLF.com, that he has set in motion plans for precisely such a place. The location, he says, would be Harlingen, Texas, a growing area in the southern tip of the state, just over the Mexico border.

Chamblee says that city officials in Harlingen are on board with the idea. He says he has also discussed the project with LPGA commissioner Mollie Marcoux Samaan, and that she sounded “excited” by it.

An LPGA representative told GOLF.com that it was “too early to share a response.”

Though the concept has yet to take full shape, Chamblee says that construction could begin within the next six months and be completed within the next two years. The design would be a collaboration between Chamblee and the Mexican-born architect Agustín Pizá, Chamblee’s partner in a newly formed design firm.

Chamblee and Pizá have already been hired for another project in Harlingen, the redesign of a course called Treasure Hills Golf Club. Chamblee says that the women’s course would be financed by the same real estate firm behind Treasure Hills, and that it would sit on a neighboring parcel, within the same development.

“We are still in the early stages of defining shot values and specifics,” Piza says. “But we guarantee, [the course] will offer a carousel of emotions for the best women golfers in the world.”

Having worked on more than 50 projects on three continents, Pizá says that he had long been aware that most courses gave low priority to the women’s game, but that he’d “never made a real analysis of it” until he listened closely to Chamblee.

For the better part of a decade, in print, on air and in the Twittersphere, Chamblee has been vocal on the issue, calling out what he regards as problematic designs and setups for women.

In nearly every respect — hole length, fairway width, rough height, bunker depth, and on — he believes the venues are poorly suited to their purpose. Far from bringing out the best in women’s games, they often place women at a disadvantage.

As far back as 2012, Chamblee put a fine point on this perspective in a GOLF Magazine column that compared scoring averages on the LPGA and PGA tours; season after season, he wrote, with a litany of stats as backup, those scores were higher for the women. In Chamblee’s view, the discrepancy had nothing to do with ability (the women were every bit as skilled as their male counterparts; they just weren’t as strong) and everything to do with the courses they were playing.

Walk a golf course with designer Gil Hanse and you’ll see the game differentlyBy: Michael Bamberger

This imbalance had ripple effects, Chamblee argued, producing higher scores but also lower ratings.

“In a world of short attention spans and ever-decreasing space in the newspapers, all sports compete with one another for an audience,” he wrote. “Scoreboards should bleed red to garner the most interest and the LPGA has applied a tourniquet in the way of courses that are set up too hard.”

In the 10 years since that piece appeared, what has changed in Chamblee’s eyes is pretty much nothing. The women still post higher average scores than the men while playing courses too long for their games. Current LPGA setups average around 6,400 yards. Extrapolating from shot data, Chamblee says, that yardage should be closer to 6,100.

Distance alone, though, is not the only issue. The crux of the problem, Chamblee says, is that courses are designed for men from the start, with after-thought adjustments to accommodate women. Pushing the tees forward is a standard tactic. But, Chamblee says, that’s not a real solution. If anything, it sets off a negative chain reaction, creating layouts with awkward landing areas, odd angles into greens, hazards placed in spots that dim strategic options. You get the gist.

Every aspect of the design would pull from available performance data, such as average driving distances, shot trajectories and dispersion patterns.

The cumulative effect is to prevent women from going lower while robbing them of chances to dazzle crowds with their shot-making skills and derring-do. It’s tough to look heroic on a lay-up par-5, or to make a ball dance around the cup when you’re hitting your approach with a hybrid and not a wedge, as elite women players are so often required to do.

As a recent illustration of this theme, Chamblee points to the 2021 Augusta National Women’s Amateur, not an LPGA event but still an elite competition. On the 18th hole of the final day, two of the top three finishers, Karen Fredgaard and eventual winner Tsubasa Kajitani, found the first fairway bunker on the left off the tee. Fredgaard caught the lip on her approach and failed to reach the green, while Kajitani didn’t even try to get on in regulation. She laid up.

Contrast that with an iconic moment from the Masters.

“Most of us have little trouble conjuring the memory of Sandy Lyle flipping a 7-iron from that same bunker to 10 feet and making birdie to win the green jacket,” Chamblee says. “Is that because Sandy Lyle is more skilled than the best women players in the world? No. It’s because he’s stronger and can get the ball up higher and faster with a more lofted club.”

The course Chamblee envisions would, in essence, aim to level the playing field. Though he and Pizá have yet to draft a detailed blueprint, Chamblee says that he can picture the concept clearly. From the tournament tees, the course would stretch roughly 6,200 yards, with room for lengthening in the future (like the men’s game, the women’s game is ever evolving). Every aspect of the design would pull from available performance data, such as average driving distances, shot trajectories and dispersion patterns.

If Brandel Chamblee were PGA Tour Commissioner, he’d change this rule firstBy: Dylan Dethier

“That means bunkers at appropriate yardages, appropriate width across the fairways, appropriate height of rough, and so forth,” Chamblee says. “We want approaches that allow the women to get the ball out on the green and spinning, providing the same excitement that the men provide.”

Among the goals would be to offer risk-rewards that he says are often missing in current LPGA setups, with drivable par-4s and reachable par-5s generating similar thrills to those produced by electrifying holes such as the 12th at Sawgrass and the 13th at Augusta.

Not that the course would be for women only. Its dimensions, Chamblee says, would also be well-suited to recreational male players, most of whom hit the ball no farther (and often shorter) than top women players. He wants a busy tee sheet for year-round public play.

Chamblee is aware that some critics may accuse him and Pizá of the architectural equivalent of “mansplaining” — just a couple of guys imposing their view of how things ought to be. But women, Chamblee says, will be involved in the project, too. One of Pizá’s longtime design partners is a woman named Avril Ortiz. She’ll have input. Chamblee says that a former LPGA star and World Golf Hall of Famer has also agreed to be involved, but that it’s too early to divulge her name.

Though courses for women have been built before, including a short-lived nine-holer at Shinnecock Hills that opened for play in 1893, male-female collaborations have been scarce outside of the husband-wife tandem of Pete and Alice Dye. One of the rare examples in the modern era is Amy Alcott’s involvement with Gil Hanse and Jim Wagner on the widely acclaimed Olympic Course in Rio de Janeiro, host site for the men’s and women’s competition in the 2016 Summer Games.

“This is the age of consideration, and it certainly feels like a time for women’s golf.” Amy Alcott

Alcott says that Chamblee is spot-on with his analyses, and that broader social and cultural shifts have made the moment ripe for change.

“This is the age of consideration, and it certainly feels like a time for women’s golf,” Alcott says. “It’s an idea I’ve been trying to get out there — that if you just throw tees out there and call them women’s tees, your course is going to be poorer for it. But beyond that, think about it from a marketing standpoint, and the ways that courses, especially resorts, are missing out.”

The Texas project, should it come to pass, would not be Chamblee and Pizá’s first crack at a course for women. Their maiden collaboration, called “The Butterfly Effect,” now underway in Desertica, Mexico, is a 24-hole resort layout composed of four six-hole loops, one of which has been designed specifically for women.

“We’re getting some good experience,” Chamblee says.

Chamblee hopes that the Texas course will inspire top women players to relocate to Harlingen, in the same way that many members of the PGA Tour have gravitated to the area around Ponte Vedra, Fla. He wants to attract emergent talent, too. To that end, Chamblee says that he envisions an elite junior golf school on the site, a kind of national academy, akin to what exists for girls in Sweden and South Korea.

He and Pizá are dreaming big.

Some things still need to fall in place for all this to happen. But Chamblee is bullish on the prospects, and, he says, he and Pizá intend to move forward with the design whether or not the LPGA gets behind it.

Beyond that, he adds, “We will continue to push for an LPGA event there indefinitely.”

A better fit for women, better late than never.

“The whole idea is to make a positive contribution to the women’s game,” Chamblee says. “I think this would be a good start in that direction.”