Ed note: On Thursday and Friday, and again today and tomorrow, Bamberger Briefly appears in memory of, and in tribute to, Charlie Sifford, often described as golf’s Jackie Robinson and a former winner of the Travelers Championship, nee the Greater Hartford Open. Thursday’s subject was Jim Thorpe. Friday’s was black touring caddies.

***

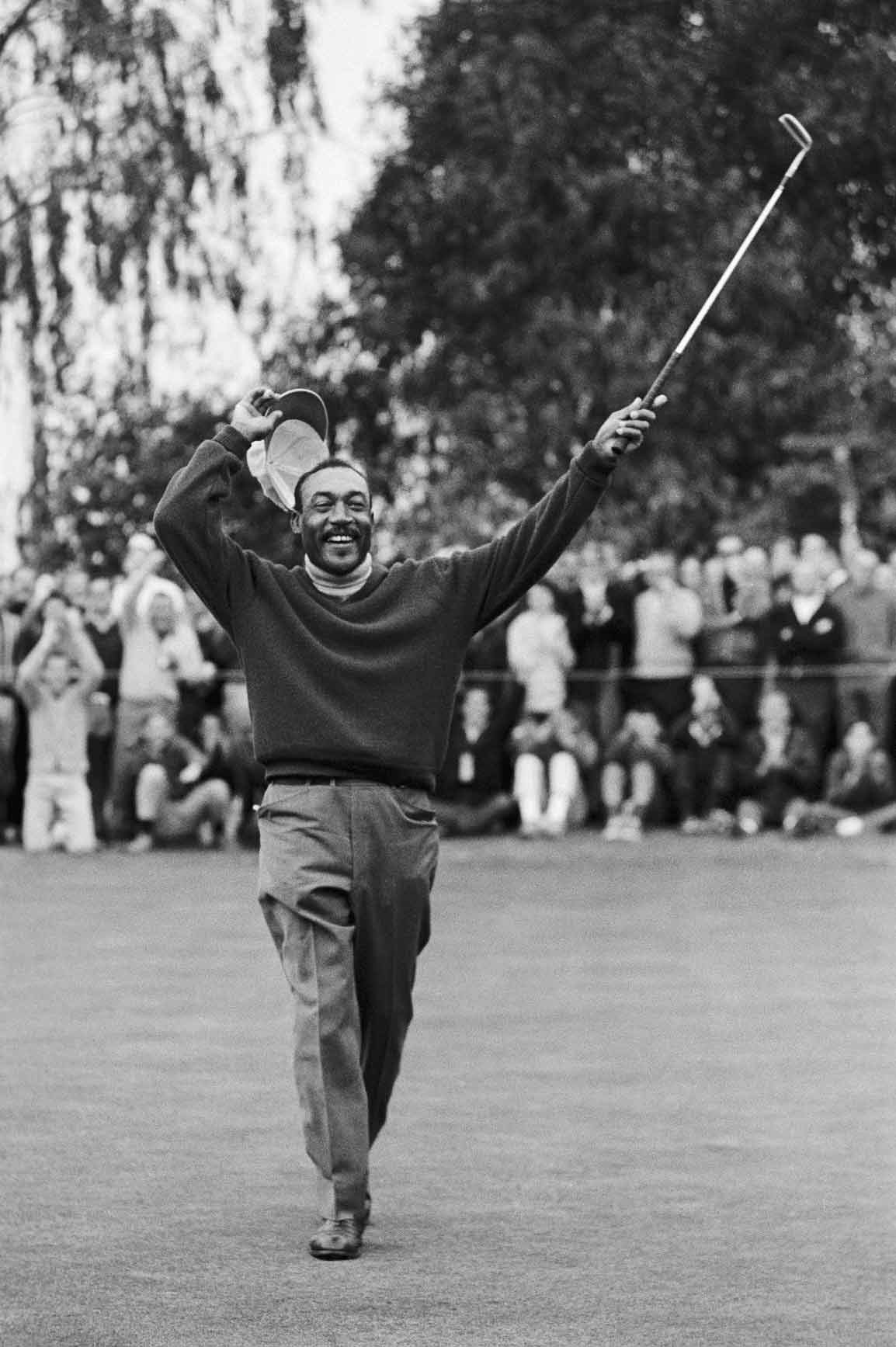

In 1964, Pete Brown became the first African-American winner of a PGA Tour event, to use two phrases that didn’t exist then. Brown’s win at the Waco Turner Open (named for an Oklahoma oilman) got Brown in the following stop, the Colonial National Invitation. Various newspaper stories noted that Brown would be the first black player to play in the Colonial and one wire story described him as a “29-year-old Mississippi-born Negro.” (Language changes as we do.) One newspaper story noted that Brown traveled the circuit with another black golfer, Charlie Sifford.

Three years later, Sifford, at age 45, won a much bigger event, the 1967 Greater Hartford Open. That win didn’t get him an invitation to the Masters. Neither did his win in the 1969 L.A. Open. Brown’s win in the 1970 San Diego Open didn’t get him an invitation, either.

Black touring caddies from a generation ago had insights you won’t find in a yardage bookBy: Michael Bamberger

You can imagine Pete and Charlie on the road together. It was surely work, just finding motels and restaurants and service stations that would welcome them. Sifford was 13 years older than Brown, and was as gruff as Brown was gentle. They traveled together to save money — and because there was safety in numbers.

I never met Charlie Sifford but I did spend part of one memorable day with Pete Brown and his wife, Margaret, in their home on the outskirts of Augusta. This was in 2014. Mr. Brown was confined to a bed but able to talk, haltingly, despite his many strokes. Mrs. Brown was vibrant, spectacularly so. In the photos from Pete’s win in ’71 she looks like a movie star, as the singer Andy Williams, the tournament host, hovers nearby.

Mrs. Brown showed me scrapbooks and in them was a letter from Tiger Woods, noting a contribution to help with Pete’s medical expenses. The sum was modest but her appreciation was immeasurable. The house itself was modest but the story behind it was also extraordinary. It was owned by Jim Dent, the successful touring pro from Augusta, who caddied at Augusta National as a kid when it had an all-black caddie yard. He invited the Browns to live in it.

It goes without saying he collected no rent. When Dent got on Tour in the 1970s, Pete Brown took him under his wing just as Sifford once showed Brown how to get around. Paying it forward would be a trite way to describe these relationships. They were looking out for each other. When Pete Brown died, two weeks after the 2015 Masters, there weren’t many write-ups.

Scott Michaux in The Augusta Chronicle was one notable exception. He had interviewed Pete Brown a number of times. “Charlie had a rough time,” Brown once told Michaux. “They harassed him a lot. I got about half of it because I came along right after him. So we were together most of the time. So whatever he got, I got, but it got better later. When he was alone by himself, I don’t know how he made it through that.”

If Jim Thorpe isn’t the most popular man in golf, he’s in the conversationBy: Michael Bamberger

“Pete was a helluva guy,” Dent told Michaux. “If he had 20 cents, he’d give you 15 cents and keep five cents he needed. So you can’t do nothing but love a guy like that like a brother.”

Charlie Woods, Tiger’s son, is named for Charlie Sifford. In between Charlie Sifford and Tiger Woods there was Pete Brown and Jim Thorpe and Calvin Peete and Lee Elder, among other pathfinders. Next week, the Tour goes to Detroit. Joe Louis, the iconic heavyweight boxer, was a god in the black golf community in Detroit. A god at Rackham Golf Course, a muni there. You can’t tell the story of American golf without these men.

Michael Bamberger may be reached at Michael_Bamberger@Golf.com