Start by locating Mamaroneck on a map: leafy New York suburb, just north of Manhattan, and home to Winged Foot Golf Club, host of the 2020 U.S. Open. Now push outward in expanding circles, up into Connecticut, east onto Long Island, across the Hudson River into New Jersey. The geographic territory you’ve traced, with a radius of roughly 100 miles, contains a couple dozen Top 100 courses, a greater concentration of such designs than you’ll find in any patch of the planet of comparable size.

This unmatched constellation includes works by Donald Ross, Charles Blair Macdonald, Seth Raynor and William Flynn, among other giants of golf ’s Golden Age. But for quantity of layouts within this cluster, one architect outstrips all the rest. He is the author of Winged Foot’s East and West courses and the undisputed titan of the tristate area: A.W. Tillinghast.

And the northeast was not his only stomping ground. Between 1911, when he cut the ribbon on his first course, Shawnee Country Club, in Pennsylvania, and 1936, when he completed Bethpage Black, his triumphant swan song on Long Island, Tillinghast is credited with contributions to upward of 260 courses across the country and into Canada, though Tillinghast biographer Philip Young says that his subject actually had a hand in many more. Prized at the time, his prolific output has only gained prestige. If you take away the Masters, held every year on the same Alister Mackenzie design, Tillinghast tracks have staged more modern-day majors than those of any other course designer after Ross.

As an architect, Tillinghast contained multitudes; some observers argue that a defining feature of his courses is the lack of a defining feature. As a personality, he was hard to pin down, too. Born into wealth in Philadelphia, Tillinghast walked in aristocratic circles but fancied himself a man of the people and lived up to that image as a vocal advocate for public-access golf. At times a tweedy figure of Victorian reserve, Tillinghast cut a raffish society profile. He was a gambler and a gadabout, drawn to high-living and high-proof libations. As hard as he could drink, he worked even harder, the artistry of his projects often matched by their ambition. Outsize in his character and his career, Tillinghast is tough to capture in a single snapshot. But with the national championship returning for the sixth time to his most acclaimed layout, Winged Foot West, it’s worth fleshing out a sketch of him. A look at five other notable Tillinghast projects within striking range of Winged Foot offers different angles on the man and the imprint he left behind.

Go Big or Go Home

Baltusrol Golf Club SPRINGFIELD, N.J.

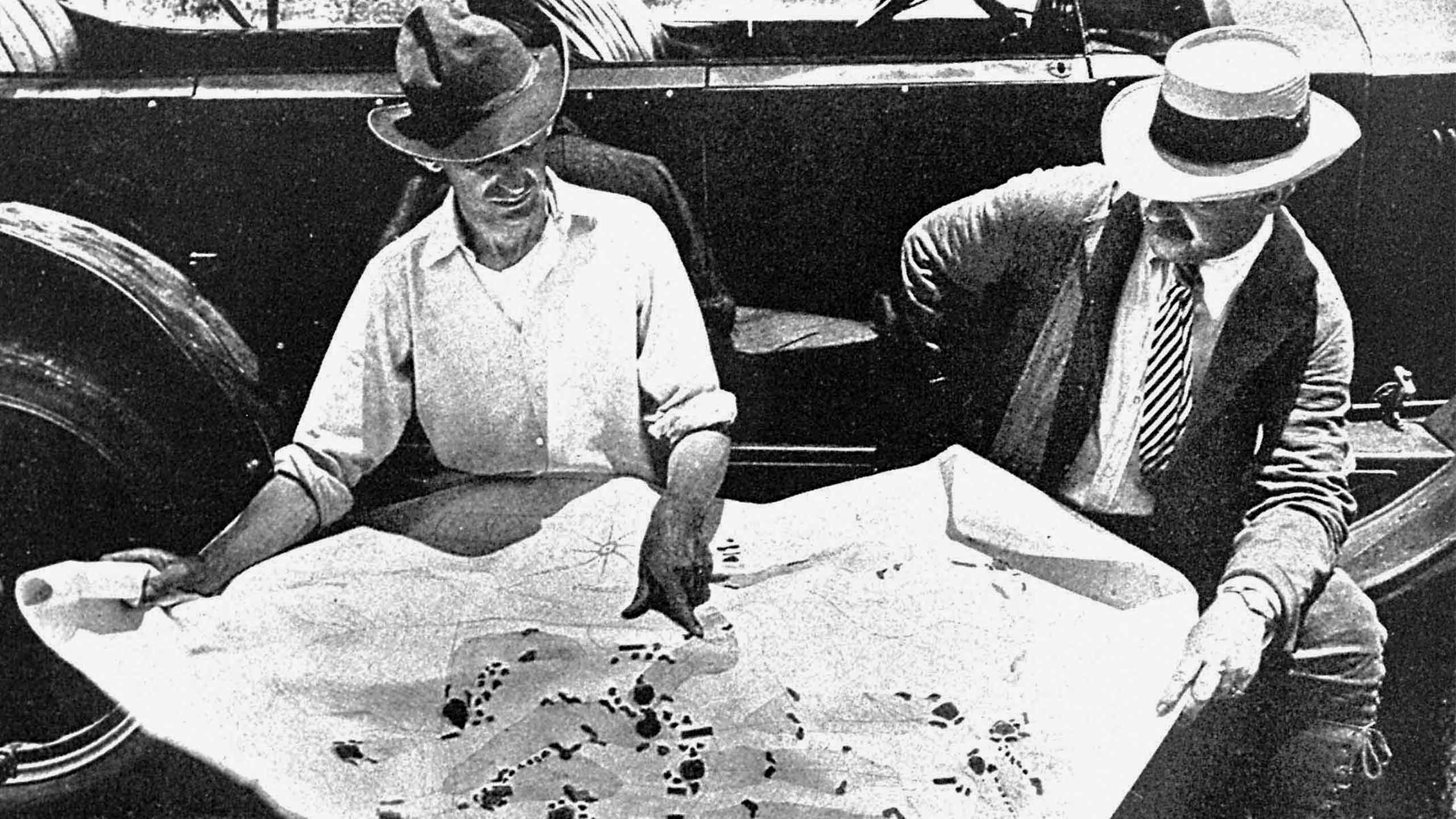

In 1918, when Tillinghast signed on to work with the club, Baltusrol already had a golf course—a two-time U.S. Open host, no less. And Tillinghast, an accomplished player in his own right, was well acquainted with it; it was where he lost to eventual champion Chandler Egan at the 1904 U.S. Amateur. Now the club wanted its 18 reworked. Tillinghast pushed for something bolder: Scrap the one course and build two in its place. In its scale and price tag, it was as audacious a proposal as the game had seen. But as a salesman and a showman, Tillinghast possessed “P.T. Barnum–like powers of persuasion,” says biographer Young. “If he really wanted to convince you of something, he could.” Baltusrol bit. It was later said that Tillinghast was the first architect ever to be given an unlimited budget. But that claim had the whiff of urban legend. And it was not the case at Baltusrol. In fact, he was given $100,000, which he blew through on his way to spending nearly twice that much to produce the club’s Upper and Lower courses. It was a grand achievement, and Tillinghast referred to it in grandiose terms: He took to calling himself the “creator” of Baltusrol. No doubt the work bolstered his renown. Among those who noticed were members of the New York Athletic Club, who had their own ambitious project in mind. They were looking for an architect to build 36 holes at a Westchester County club they would call Winged Foot.

Breaking the Mold

Somerset Hills Country Club BERNARDSVILLE, N.J.

Like Charles Blair Macdonald, Tillinghast spent formative time in Scotland. But unlike his fellow American designer, he did not return from the British Isles bent on reproducing what he’d seen. Where Macdonald was the king of architectural homage—Road holes, Cape holes, Punchbowls and the like—Tillinghast mostly turned his back on tributes. Though he did have a penchant for repeating certain features (he proudly claimed to be the father of the “double-dogleg”), those signature touches were his own. More traditional templates held little interest for him—unless, he said, the land cried out for them. Somerset Hills was a rarity, a site where Tillinghast heard that call. The course, which consists of two contrasting nines—the front side meadowy, the backside wooded—has been hailed as a museum piece for its striking display of templates. On the par-4 13th hole, a Principal’s Nose bunker—a nod to St. Andrews—sticks its sandy schnoz out of the fairway, roughly 60 yards in front of a Biarritz green. The 16th, a midrange par 3 with a sloping green guarded by a deep bunker, evokes, for some, an Eden hole. (Others dispute this.) Most notable is the long par-3 2nd, which plays over a valley to a green that tilts down and away from its daunting front-right point of entrance. It’s a Redan, and many say it surpasses the original at North Berwick. In Tillinghast’s hands, it wasn’t imitation; it was emulation at its most inspired.

Playing the Trifecta

Ridgewood Country Club PARAMUS, N.J.

In one of many magazine articles he authored, Tillinghast described the ideal setting for a golf course as sandy, contoured seaside land. Yet unlike Mackenzie, Ross and others of his era, he was never given a world-beating coastal site. That he made hay farther inland, often coaxing greatness from mundane locales—Winged Foot is widely seen as a prime example of an A-plus course on C-plus terrain—stands as one of many testaments to Tillinghast’s genius. Another of his talents was rising to the challenge of his clients’ demands. In the case of Ridgewood, the mandate he was given was a first of its kind: Not only did the club want three separate nines—a rarity in itself—it wanted three nines of equal caliber, without a red-headed stepchild in the bunch, all slated to open at the same time. On top of that, because the trio was meant for mix and matching, each nine had to work back to the clubhouse. “That’s six holes starting or ending from essentially the same point,” Young says. “The difficulty of the entire project is astounding.” It had never been done, but Tillinghast did it, working up, down and along the property’s wooded ridge, spreading artistry evenly around the grounds. The balance he achieved is punctuated by the fact that when big-time tournaments like the Barclays are held at Ridgewood today, the East, Center and West courses each contributes anywhere from five to seven holes.

A Study in Contrasts

Quaker Ridge Golf Club SCARSDALE, N.Y.

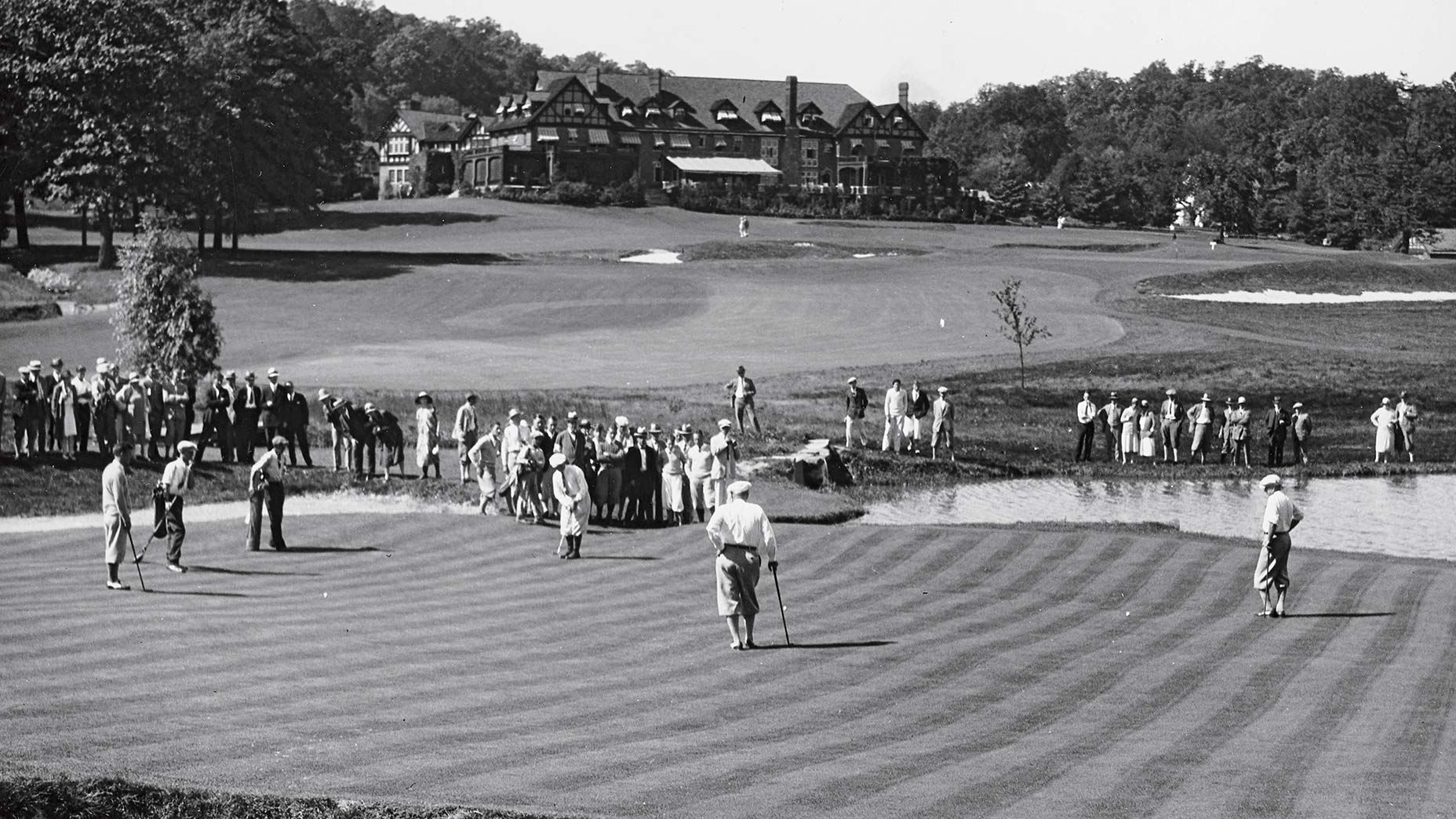

For a succinct, spot-on assessment of another of Tillinghast’s major works, take a spin through time to the 1974 U.S. Open at Winged Foot, where Jack Nicklaus was asked if he believed that the host site was the finest layout in the world. “That may be,” Nicklaus replied. “But there is quite a golf course down the street.” Across the street, more like it, no more than a short par-4 away. First opened for play in 1918, Quaker Ridge was overhauled by Tillinghast seven years later, so its vintage is similar to Winged Foot’s and its parentage is the same. But as with many siblings, the two properties have vastly different traits.

At Winged Foot, where Tillinghast was given a flat expanse and asked to build a beast, the architect obliged by building some of the world’s most fearsome greens, rising from the fairways, bold, defiant. Quaker Ridge, by contrast, has much calmer putting surfaces but the land itself is far more lilting. A former Quaker Ridge head professional was fond of saying that at Winged Foot you made bogey from the fairway—you have to be deadeye with your approaches—where at Quaker you made bogey from the tee. On this more rollicking terrain, Tillinghast deferred to the contours as he found them. His light touch reflected his conviction that you shouldn’t try to manufacture nature when nature had already done a fine job on its own.

Power to the People

Bethpage Black FARMINGDALE, N.Y.

Golf courses as “mankillers.” Credit Tillinghast with that coinage and that concept, which he fleshed out in an article of the same name. The original “mankiller,” he wrote, was Pine Valley, his pal George Crump’s acclaimed layout in New Jersey. It could break you physically with its shot-making demands, even as it shattered your heart with its beauty. Tillinghast dreamed of spawning such a creature.

In the mid-’30s, at Bethpage State Park on Long Island, he got his chance. All the better, as he saw it, the Black Course was a man-killer for the Everyman. Monied by birth—his father owned a successful rubber goods company—Tillinghast was keen on extending the game’s reach beyond the wealthy. That most of his commissions were for private courses was more reflective of the era than of his leanings.

In his writings and other pronouncements, the high-living course designer proved himself a champion of golf for all. Bethpage married his abilities and his interests. The job required a massive effort on par with his ample ambitions: He was hired to build three courses, the Black, Red and Blue, and overhaul a fourth, which became known as the Green. According to Philip Young, never has a single architect had a hand in so many courses at one site at one time. Of the bunch, the Black Course was Tillinghast’s baby, and a brawny one at that. He took special pride that it was also a muni, a fitting closing act in an astounding career, a man-killer destined to endure.

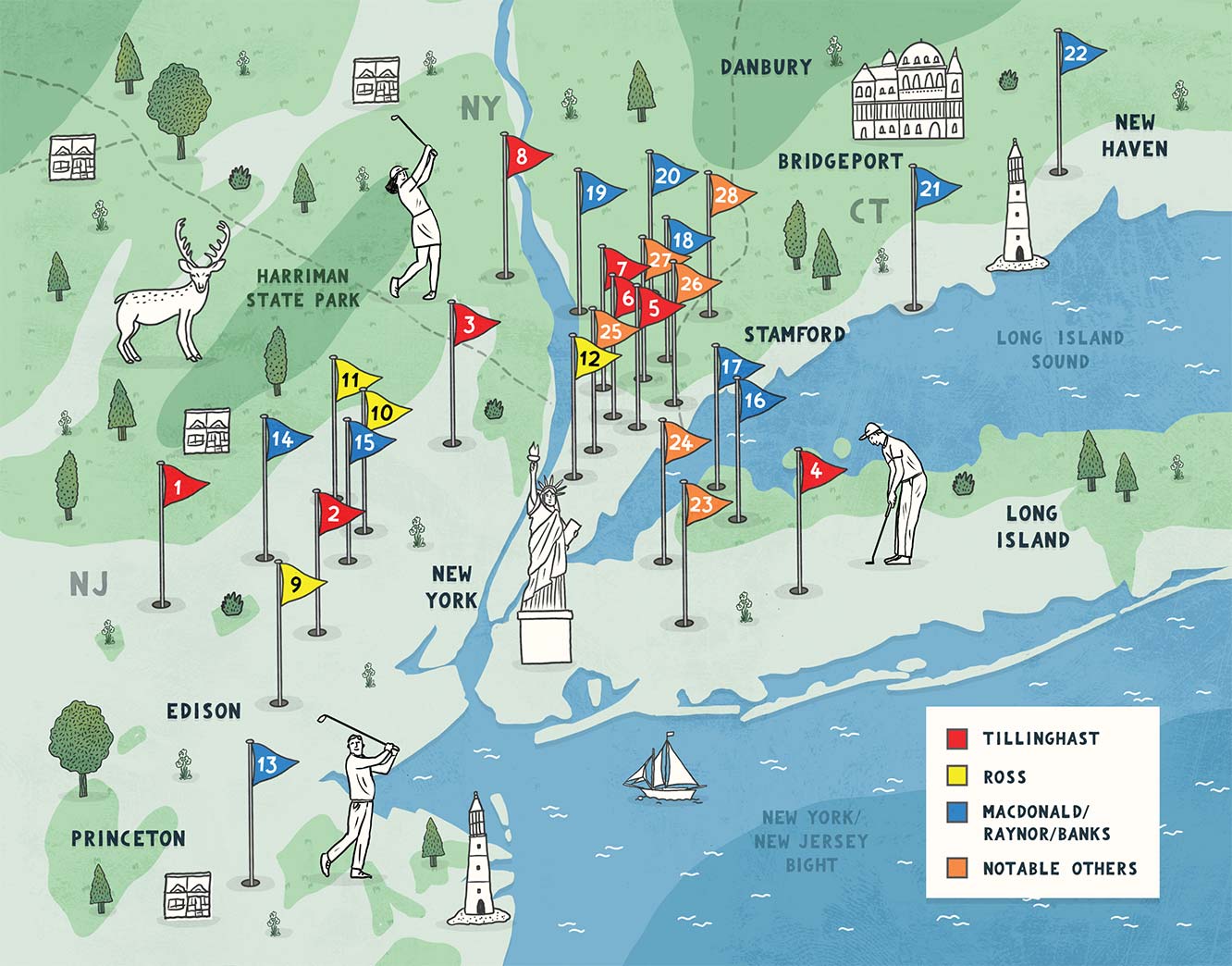

Flag Hunting

Tillinghast, Ross and Macdonald and his disciples went wild in the tristate (NY, NJ, CT), creating, arguably, the most astonishing cluster of marquee courses in the world — and this map doesn’t even include the titans on the tip of Long Island: Shinny, National, et al. Hit a drive from any highway here and it might find a Top 100 fairway. *map key below*

A.W. Tillinghast

1. SOMERSET HILLS CC Bernardsville, N.J.

2. BALTUSROL GC Springfield, N.J.

3. RIDGEWOOD CC Paramus, N.J.

4. BETHPAGE BLACK Farmingdale, N.Y.

5. WINGED FOOT GC Mamaroneck, N.Y.

6. QUAKER RIDGE GC Scarsdale, N.Y.

7. FENWAY GC Scarsdale, N.Y.

8. PARAMOUNT CC New City, N.Y.

Donald Ross

9. PLAINFIELD CC Edison, N.J.

10. MONTCLAIR CC Montclair, N.J.

11. MOUNTAIN RIDGE CC West Caldwell, N.J.

12. SIWANOY CC Bronxville, N.Y.

C.B. Macdonald, Seth Raynor and/or Charles Banks

13. FORSGATE CC Monroe Township, N.J.

14. MORRIS COUNTY GC Morristown, N.J.

15. ESSEX COUNTY CC West Orange, N.J.

16. PIPING ROCK CLUB Locust Valley, N.Y.

17. CREEK CLUB Locust Valley, N.Y.

18. BLIND BROOK CLUB Purchase, N.Y.

19. SLEEPY HOLLOW CC Scarboroughon-Hudson, N.Y.

20. WHIPPOORWILL CLUB Armonk, N.Y.

21. CC OF FAIRFIELD Fairfield, CT

22. YALE GOLF COURSE New Haven, CT

Notable Others

23. GARDEN CITY GC Garden City, N.Y. (Devereux Emmet/ Walter Travis)

24. DEEPDALE CC Manhasset, N.Y. (Dick Wilson)

25. WYKAGYL CC New Rochelle, N.Y. (Tillinghast/Ross/ Lawrence Van Etten)

26. WESTCHESTER CC Harrison, N.Y. (Walter Travis)

27. CENTURY CC Purchase, N.Y. (C.H. Alison)

28. THE STANWICH CLUB Greenwich, CT (William and David Gordon)

Editor’s Picks

Bethpage Black vs. The Fool: How I tried to devour (yet another) high-handicap hacker

This under-the-radar Tillinghast design is perfect for course architecture nerds

What it takes to win a U.S. Open at Winged Foot, according to two players who have done it