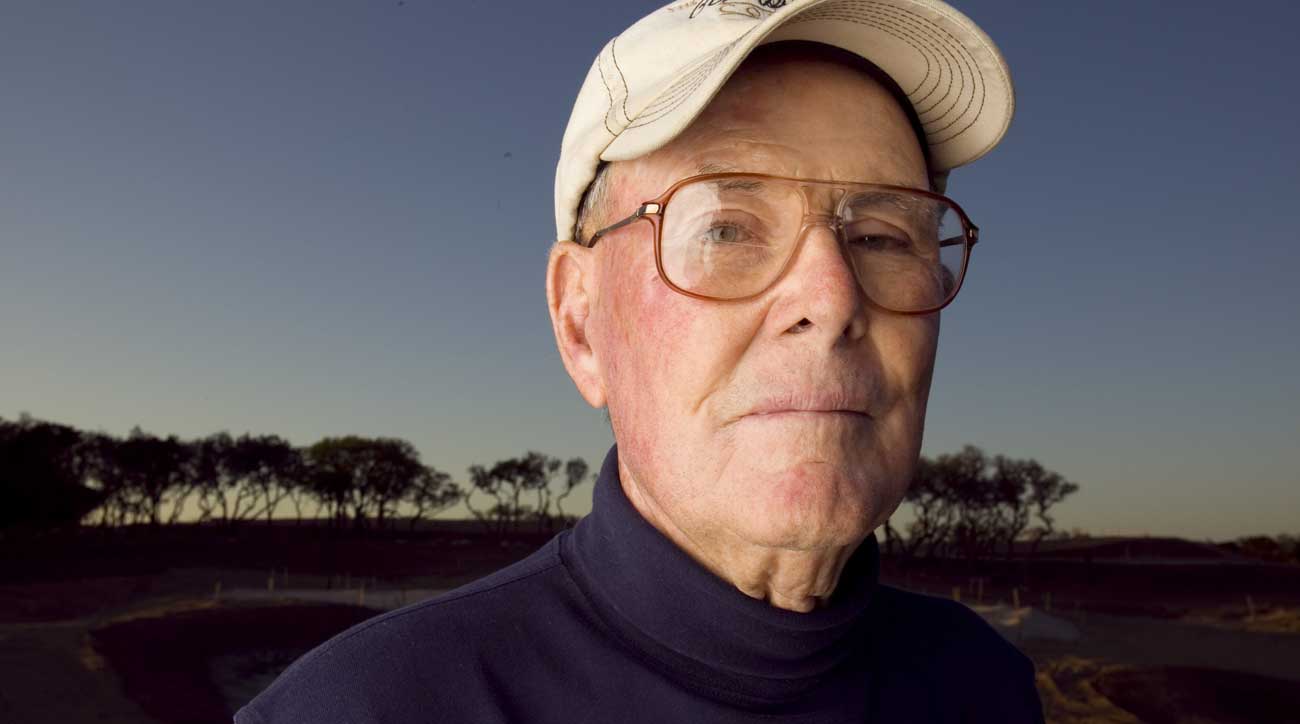

If you’re into golf-course architecture — and who among us is not? — this won’t be news: this Gil Hanse is everywhere. Last year’s U.S. Open at Winged Foot? Resto’ by Hanse. This year’s U.S. Open (women’s edition) at Olympic? Another Hanse joint. Southern Hills, where the 2022 PGA will be played, and The Country Club, site of the 2022 U.S. Open? G. Hanse, G. Hanse. The Yale course redo? The Merion East nip-and-tuck? The Pinehurst No. 4 reinvention? Yada. Yada. Yada.

So you can imagine our collective surprise when we, a handful of a Redan-o-philes, learned, during an on-site Ryder Cup walk with Hanse as our shepherd, that the man was making his first trip to Whistling Straits, the must-see American golf resort, pricey and spectacular. Oceanside golf in Wisconsin, even if the body of water along its shore is technically a mere lake. Redan, you may know, is a term of war and also a term of golf-course architecture. It’s a meaty word though I can’t say I’ve ever really understood it. The word came up more than once, as we walked the course.

What is a Redan hole, plus how identifying one can help your gameBy: Desi Isaacson

“Never been here before,” Hanse said. “But I did play with Pete once, at Hilton Head. He carried his own bag, played fast and played great.” Hanse’s Pete was the late Pete Dye, who built Whistling Straits, the Harbour Town Golf Links (aka Hilton Head) and loads of other courses. In manner, Hanse (reserved) and Dye (outrageous) were opposites. As architects, ditto. But Hanse’s reverence for Dye, over the course of our walk, became obvious.

One member of our group, a style writer and golf blogger named Michael Williams, was wearing a golf hat of his own design with one word stenciled across its brim: redan. The first letter was lower case and there was a period after the n — and those things made all the difference.

Also in the group was a slender young gent named Ben Boskovich, an editor at Esquire, the stylish magazine that coined the phrase “Man at his Best.” Boskovich was wearing a hat bearing the name Aimé Leon Dore. You know, the New York-based street-meets-club fashion brand. OK, yes: I looked it up. But I can tell you something about Jos. A Bank fall collection.

To keep the theme going here, Hanse was wearing a Southern Hills baseball cap, various Peter Millar golf duds and, on his wrist, a heavy Rolex. That was not a coincidence. Our little walk was organized by Rolex.

When I first met Hanse, nearly 30 years ago, he was wearing dungarees and L.L. Bean boots and he came off a bulldozer to say hello. Today, Hanse and his work colleagues use a name that descends, in its way, from Man at this Best: Caveman Construction. It’s the push-the-dirt side of Hanse Golf Design.

“Wearing a Rolex and a golf hat at the same time, it’s a nice sweet spot,” Boskovich told me later, when I asked him to size-up Hanse’s style sensibilities. “It speaks to where the game of golf is right now. I’ve golfed with guys wearing jeans shorts, and I’ve golfed with guys dressed like Tour pros. We all love the game.”

It’s always neat, getting a fresh perspective on anything, and that was one. Golf needs more players in jean shorts, and more people who use golf as a verb. As for the hoodie in golf, that’s not even a question anymore. You likely saw the American players wearing them at Whistling Straits. Wearing, not rocking. Please. That’s so 1996. Collin Morikawa wasn’t even born.

I first met Hanse in 1992, when he was starting out in the biz and working for Tom Doak. Doak, when he was starting out, worked for Dye. There’s a lot of that in golf-course architecture, a lot of Mungo begat Old Tom and Old Tom begat D. Ross and D. Ross begat — just about everybody.

Six degrees, golf-style.

And as Gil Hanse once golfed with Dye, Dye golfed (take it up with my editor) with Donald Ross. And as Dye made a study of the great Scottish courses, Hanse did the same. In passing, Hanse talked about Dye’s use of railroad ties, a common way to hold up bunker walls in the Motherland, and easy to find over there. The wooden ties were lying about, detritus from the railway lines in coastal Scotland. A lot of trucks once roamed the Straits course, in its embryonic stages. At Whistling Straits, the railroad ties were trucked in. Hanse’s thing is to use, as best he can, what Mother Nature provides him. Dye’s thing was something else.

Pete Dye was an ageless wonder, and there will never be another course designer like himBy: Michael Bamberger

Hanse told us something I should have known but didn’t: When Dye and Herb Kohler, the plumbing-fixtures magnate and golf nut, started talking about a golf course on the shore of Lake Michigan in rural central Wisconsin, the entire tract was dead-flat farmland. All known evidence of that origin story is gone. Hanse talked about a small mountain Dye built at the end of the Whistling Straits property, beyond the 5th hole, to block out the view of the neighboring flatlands and farmland. That made an impression on Boskovich, both what Dye did and Hanse’s description of it. Boskovich’s interpretation of it made an impression on me.

“When Dye put that mound there, it was his way of saying, ‘You’re on the course now, and you don’t want to be anywhere else.’” That comment made me think of Augusta National as a golfing oasis. For a lucky few, you get beyond chaotic Washington Road, past the club’s imposing wall, and then you’re in a golfing dreamscape.

The Old Course, come to think of it, is like that, too, but in a different way. You start in town. You leave town. You finish in town.

There are many ways, to the heart of golf. They’re all good. Still, there’s a reason why the Grand Slam events are almost never played on courses lined with homes. There’s not a single home on the Straits course. Golf is, among other things, a form of escape.

If you think of Whistling Straits as an American version of Scottish linksland, you likely have transported yourself to the West Coast of Scotland, where the land heaves, and not the East, where it does not. Hanse said that Whistling Straits might look like a true links course, but it doesn’t play like one. The ball doesn’t roll out. It doesn’t tumble. Hanse, tall and measured, was standing on a manmade hill, looking at a manmade course, Lake Michigan shimmering (literally) beyond it.

Hanse imagined a course that he might have built there, a course with a much lower profile. No towering anything. Hanse is a minimalist. Dye was a maximalist. The old Scottish architects often talked about the hand of God at work on the great courses. Dye was an archetype American course designer, as Hanse described him. A golf-course builder, really. Hanse said he considered himself a builder, too, but his aesthetic is totally different.

Hanse said that Whistling Straits might look like a true links course, but it doesn’t play like one.

As we walked the course Hanse chatted about this and that. He started out as a history major in college (he went to the University of Denver) and switched to landscape architecture. But history is always tugging at him. He said that, in his experience, Merion and Yale had the best archival materials about their courses, and he goes back to them again and again. He cited Ben Crenshaw and Geoff Ogilvy as two elite players who were world-class in their knowledge of golf-course design, and golf-course history. The two go hand-in-hand, to a point.

Dye died last year, and this year was some tribute to him. Justin Thomas won the Players at TPC Sawgrass, a Dye course. Phil Mickelson won the PGA Championship at Kiawah, a Dye course. Stewart Cink won at Hilton Head. The U.S. won the Ryder Cup at Whistling Straits. Next year will be a good one for Hanse, if you’re talking about main-stage golf. Of course, there’s way more to golf than that. Dye’s landmark courses are ones you might play once in your life. That’s not where Hanse goes.

“Listening to Gil, you could hear how the architects want to innovate, they compete with each other, and that’s good for the game,” Boskovich told me. “They’re artists. They’re innovators. That’s why not all golf courses look the same.” An excellent insight and observation.

The walk was about 90 minutes or so, and then lunch was served. You can imagine the scene: red wine or white, your choice. Tom Watson, holding court. Before going in, Hanse, his wife, Tracey, alongside him, looked at a large electronic leaderboard. “We’re up in three, down in one,” he said. The U.S. win was coming.

Kohler wanted a destination golf course and he hired Dye to build him one. They got what they wanted. The Ryder Cup was at Whistling Straits. Gil Hanse was taking it in.

Michael Bamberger welcomes your comments at Michael.Bamberger@golf.com.