He had played tennis for most of his adult life, but as the years wore on and the classic sore elbow started to set in, the late Washington, D.C., developer and philanthropist Robert H. Smith began dabbling in golf. One summer that included a memorable trip to Scotland and his first exposure to links golf. When Smith returned to his 500-acre Heronwood estate in Northern Virginia, the game was very much on his mind.

Smith, who died in 2009 at age 81, decided at first to put in a natural grass putting green not far from the main house. Then he had three regulation holes built in 2003, “just to see how he liked it,” according to Ben Rogers, Heronwood’s long-time farm manager who still oversees the care and maintenance of the entire property.

“We built six more holes in 2005, added three more in 2006 and then got final approval from the county (Fauquier) to do the last six holes and make it 18,” Rogers said. “When Mr. Smith first said he was thinking about a golf course, I thought he was joking. One day he looked at me and said, ‘I think I’m going to do it. What do you know about building a golf course?’ I told him absolutely nothing. Then he said, ‘That’s okay, we’ll learn it together.’”

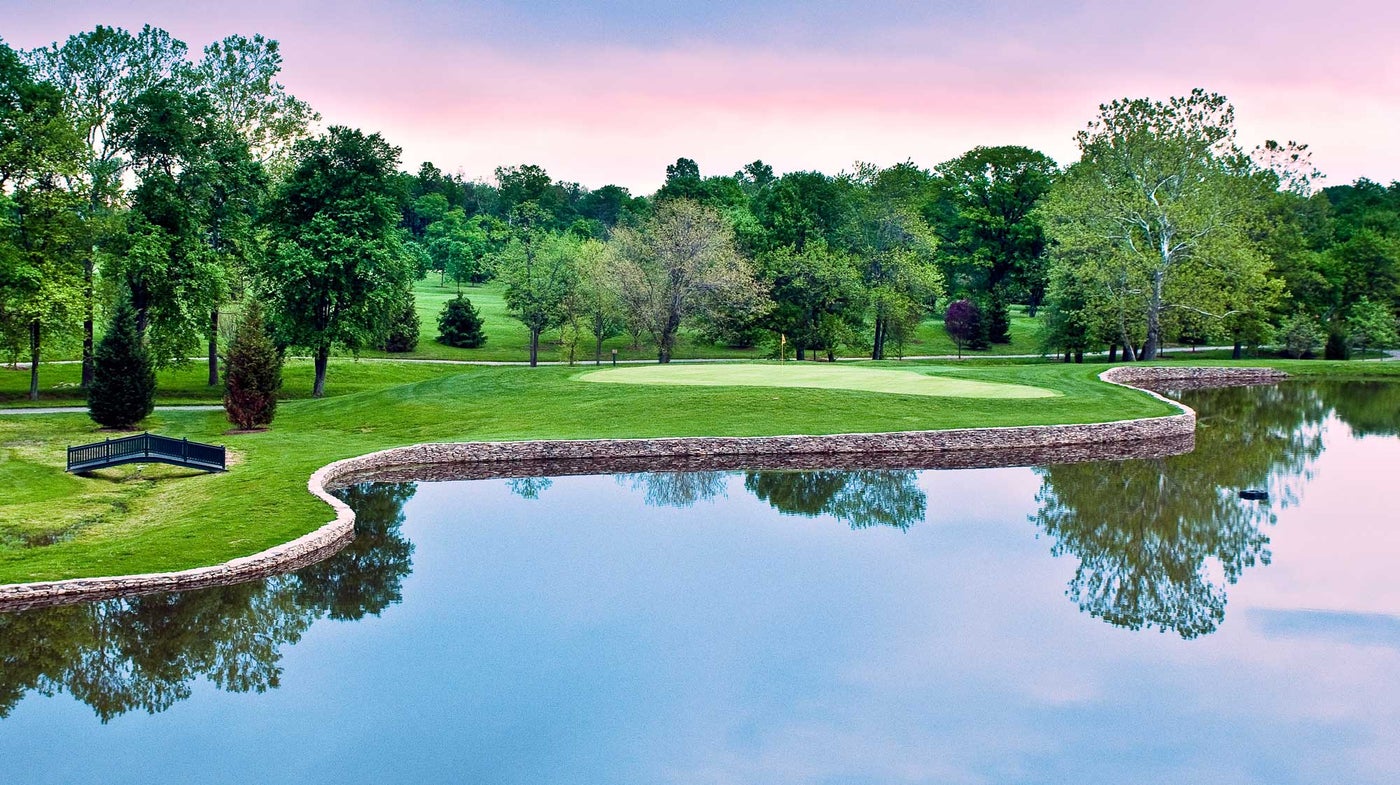

The entire course was completed in 2007, laid out over a 130-acre swath of land that had once served as cornfields and pastures for the estate’s considerable horse and cattle population. Now, 13 years later, it remains one of the most private golf courses in America, if not the world.

To build it, Smith retained the services of the Washington area golf architectural firm of Ault, Clark & Associates. The company has designed, built or renovated hundreds of courses around the country, including Congressional Country Club, Kingsmill in Williamsburg and several TPC venues owned by the PGA Tour. Brian Ault, the son of company founder Ed Ault, handled the design and oversaw the construction, with plenty of input from the owner.

Rogers estimated that no more than 25 golfers have played the full 18-hole Heronwood course since it was completed. The 6,300-yard par-71 venue — which easily could be expanded — includes four sets of Bermuda grass tees on each hole. Fairways also are Bermuda, and the expansive greens are all bentgrass.

As a long-time golf writer, I’ve been fortunate enough to have played some of the world’s most storied courses, including Augusta National, Pebble Beach and St. Andrews. And yet, for many years, one course on my bucket list had remained elusive.

That would be the late Mr. Smith’s Heronwood, located in the tiny, tony town of Upperville, Va., once immortalized in a John Updike poem. It’s an hour west of the Nation’s Capital in Virginia horse country, but merely five miles from my own front door. It’s also less than a mile from the estate of the late philanthropists Paul and Bunny Mellon on Rokeby Road, one of the most gorgeous thoroughfares in all of Virginia.

This past May, Smith’s widow, Clarice Smith, allowed me to play this truly pristine gem. A highly regarded octogenarian artist whose works grace countless homes, galleries and museums, she often played with her husband, and continued swinging away until last fall until a knee injury sidelined her.

The course is plenty challenging, despite fairways that are fairly wide and mostly flat. There are several dog legs and the rough is thick and long enough to punish errant shots and cause balls to occasionally disappear. Water comes into play on a number of holes, with expansive bunkers protecting every green and plenty of places on the undulating putting surfaces to locate tricky pin placements.

Each of the dozen ponds features spraying fountains turned on only when someone is playing. Life preservers are strategically positioned close to every pond, just in case someone falls in.

The entire farm, including a classic Revival-style manor house, three other houses and several apartments, is now up for sale at a price of $19.5 million, recently reduced from its original $24.5 million price tag. The hope is that whoever purchases Heronwood will keep and maintain the course just as it is, and limit play to their own guests, just as the Smiths have always done.

Robert Smith was best known as the major developer of an area known as Crystal City, in Virginia, just across the Potomac from Washington and a driver and wedge from Reagan Airport. When Smith died, his company was the single largest property owner in the Washington region.

Smith took over his father’s businesses, the Charles E. Smith companies, in 1967 and ran them for many years with his brother-in-law, Robert P. Kogod. Together they transformed the family-owned construction firm into a multifaceted real estate empire, building office complexes and apartment houses and eventually becoming Washington’s largest commercial real estate landlords.

Smith and his wife also gave back in a big way. They’ve donated hundreds of millions of dollars and pieces from their precious art collections to universities, museums and historic landmarks. He was the single largest donor to his alma mater, the University of Maryland, which named its business school after him in 1998. The school’s performing arts center is named for Clarice Smith.

He told me one of the nicest things about owning a golf course was that you could hit a bad shot and just drop another ball down.

In the early years of golf at Heronwood, the Smiths both walked their course when they played, towing hand carts.

“Then they got those self-propelled hand carts, and finally they bought two real golf carts,” Rogers said. “He’d come out on a Thursday and usually play three or four times on the weekend, and sometimes it was just the two of them. Occasionally they’d have a guest. The most people we ever had on the course at one time was probably four.”

When I played Heronwood in mid-May, Rogers said I had been the only golfer on the course in the first four-and-a-half months of 2020.

Smith was a decent player, probably a 15- to 18-handicapper. Rogers said the owner recorded two holes-in-one on his course and “took the game pretty seriously. But he also told me one of the nicest things about owning a golf course was that you could hit a bad shot and just drop another ball down and hit it again. You’re sure not going to hold anyone up.”

A full-time course superintendent remains on the payroll, 29-year-old Tyler Day. He’s a Virginia Tech graduate who had been an assistant superintendent at several local courses until he came to Heronwood in 2017 for what he called “an opportunity that sounded too good to be true.”

“It’s a little different not having many people actually playing the course you’re taking care of,” Day said. “I got along great with the members at the other places I worked, and I miss that kind of communication. The good part here is you can get things done pretty quickly. There’s no foot or cart traffic, so you obviously can keep the course and the greens in better shape. I like to see people play and enjoy it and I take pride in what we’ve done. That definitely keeps me satisfied.”

Day said he’s never played the course himself other than a bit of chipping or putting, and that’s fine with him.

“Working here is a career thing for me,” he said. “It’s just a special opportunity to take part in something so unique and so exclusive.”

It’s a little different not having many people actually playing the course you’re taking care of.

How long it will stay that way remains to be seen, what with the entire 500 acres on the market.

Because the property is in conservation easement, it could never be developed by a single owner as a gated golf community with houses all around the course. But it can be carved into 100-acre parcels that would allow each buyer to build a home and even add a few tenant houses on their individual properties.

Several potential buyers have come out and looked around, and a few have even played the course. One possible sales scenario would be for a small syndicate to buy the estate, keep the course, live on the property and perhaps turn the facility into a small, very private membership club.

There’s a gorgeous 10,000-square foot horse barn on a hill overlooking the course, and it could easily be converted into a functioning clubhouse. There’s no formal practice range, but Rogers said Smith often took a shag bag over to the farm’s well-manicured polo field to work on his game.

The current “clubhouse” is a small shed that includes a refrigerator with cold drinks and few kitchen cupboards for snacks and dishes. There’s no cart barn. The two carts fit snugly together in another 12-foot x 20-foot shed that also houses several extra sets of clubs.

Rogers does not know the original cost, but estimated a similar course these days would probably be in the $8 to $10 million range, “which is conservative.” The upkeep now ranges between $500,000 and $600,000 a year, and superintendent Day has a staff of four.

“The hope is that whoever buys it will keep the farm and the golf course as is,” Rogers said. “Keep the staff and run it like it’s been run the past 35 years. The sale includes all the equipment and the full staff is available to the owners, me included on a consulting basis.”

The hope is that whoever buys it will keep the farm and the golf course as is. Keep the staff and run it like it’s been run the past 35 years.

The course’s scenery is stunning, with the Blue Ridge Mountains visible in the distance. Smith had 2,000 now mostly mature trees from a nearby nursery planted all around, and a full-time farm arborist helps maintain them. To ensure Mrs. Smith would never have a problem locating her tee box, a tall Japanese maple was placed only a few yards from the front driving area on every hole.

For any golfer, it’s a living, breathing fantasyland. The day I played, I spotted several foursomes of deer dashing down the fairway. Foxes, the occasional bear, and all manner of bird species have been seen on the property. A gorgeous gurgling mini-waterfall cascades about 60 yards from the 17th green, and with all those ponds, it’s a fisherman’s paradise, too.

As a single in a cart, it took me only two hours to play 18 holes, including more than a few mulligans. There were a couple of pars, a near chip-in birdie at the 6th hole and a twisting 25-footer for bogey at No. 17.

A return visit to Heronwood will remain on my bucket list. After all, I now have a bit of course knowledge in my back pocket. Plus, it’s hard to beat the six-minute commute home.

Leonard Shapiro covered golf for The Washington Post for 20 years and is a former president and current board member of the Golf Writers Association of America.