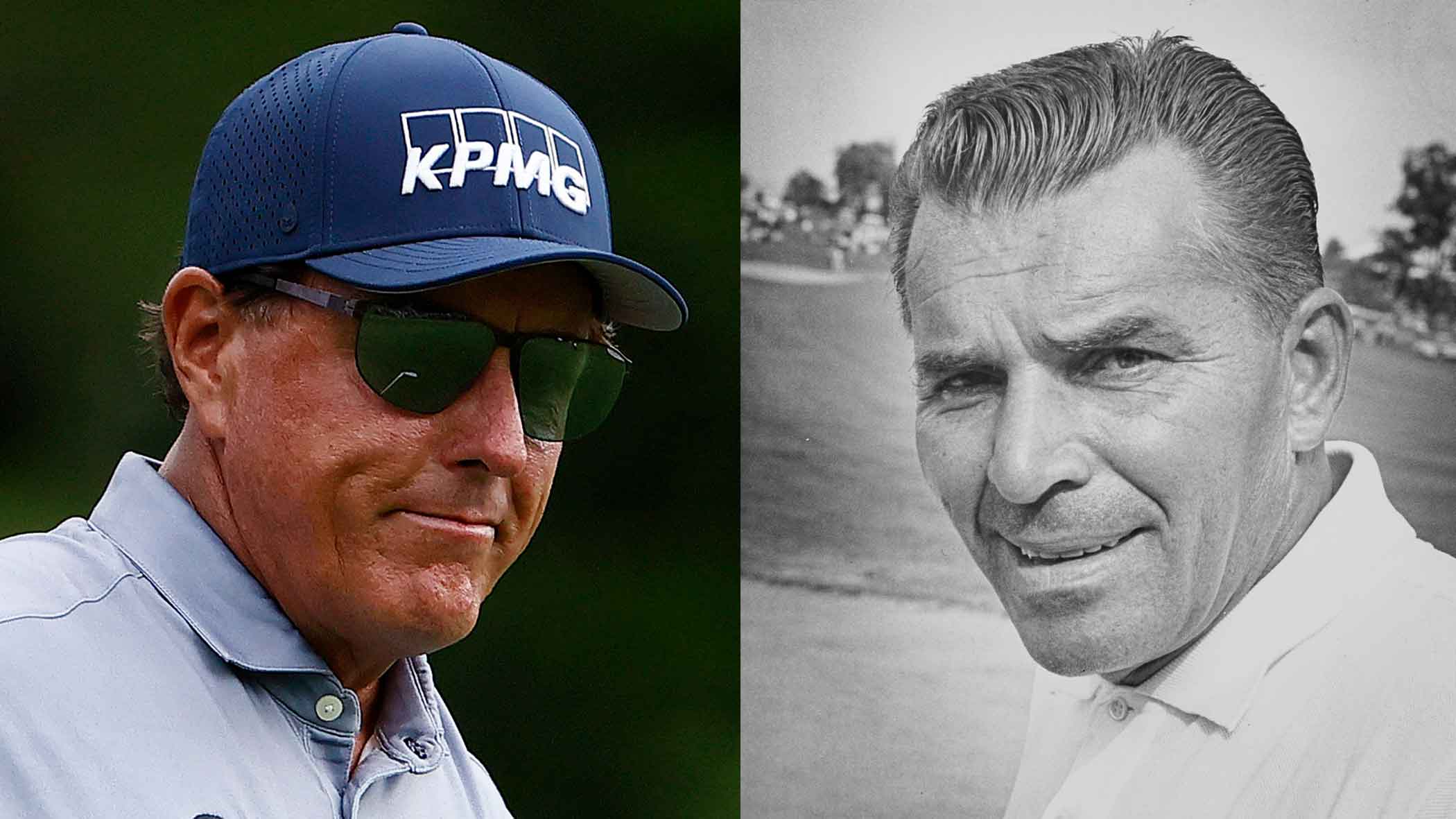

When Phil Mickelson broke Julius Boros’ 53-year-old record, Boros’ son was watching

When Phil Mickelson won the PGA at 50, he beat Julius Boros' mark by two years.

getty images

Julius Boros and his wife, Armen, had seven children, and one of them, Guy, played the PGA Tour for years. In fact, Guy shot 63 at Colonial the day before his father died, in 1994. Julius Boros, you probably know, was the oldest player to win a major, until Phil Mickelson won the PGA last month. Boros was 48. Mickelson was 50. Guy knows and gets what Jack Nicklaus has been saying for years about Tiger Woods and his pursuit of Nicklaus’ record of 18 major titles: I’m not rooting for him to break it, but if he does, I tip my hat to him.

Asked recently what it was like to watch Mickelson play on Sunday at Kiawah at the PGA, with his dad’s title as OPTWAM on the line, Guy Boros said, “It’s happened before. Tom Watson at Turnberry, when he should have won.” The 2009 British Open, when Watson was 59. “For me, it’s pretty similar to what Jack says,” Boros said. “It was nice to have my father’s name in circulation.”

Julius Boros’ record, as the oldest player to have won a major, held up for 53 years. He turned pro at 29 and was an amazing talent. In the 1950s and ’60s, he played in 19 U.S. Opens and had top-10 finishes in 11 of them. In 1973, at the U.S. Open at Oakmont, Boros had a top-10 finish at age 53. Mickelson turns 51 on Wednesday. If he can win the U.S. Open on Father’s Day at Torrey Pines, his current record for OPTWAM will have expired after all of five weeks. Things are so fast these days. But both he and Boros were good for eons.

Boros won two U.S. Opens, in 1952, at Northwood, in Dallas, and in 1963, at The Country Club, in Brookline, Mass. The next time the U.S. Open was played at The Country Club, in 1988, it was spruced-up for the occasion by Rees Jones, the golf-course architect and the son of a famous golf-course architect, Robert Trent Jones. The senior Jones designed and owned Coral Ridge Country Club, in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., where the Boros family lived for a half-century, right off the 9th green.

Lexi Thompson’s maternal grandfather delivered milk to that house — and also, now and again, ice-cream sandwiches, as Guy Boros remembers fondly. Rees Jones used to have a move that the instructor Jimmy Ballard taught, where your shoulders rock away from the ball in the first part of the takeaway. Curtis Strange made that Ballard move all through his professional career. Julius Boros tried to get Rees to make more of a shoulder turn and do less rocking. Strange won that U.S. Open at The Country Club in 1988. He also won in 1989, at Oak Hill, in Rochester, N.Y., where Trent Jones Sr., 100 or more years ago, fell for the game, as a caddie and golfer, on that city’s fabled courses. Rees Jones once played in the Pebble Beach pro-am tournament with Guy Boros. Guy Boros and Rees Jones will both tell you the same thing: Golfers love meeting U.S. Open champions, and they love playing U.S. Open courses.

Yes, that was a long, strange trip to the end of the preceding paragraph, but golf itself is a long, strange trip.

Guy Boros remembers riding in a convertible, not yet four and sitting on his father’s lap, somewhere in South Florida, at a small parade in his father’s honor after the 1968 PGA Championship. Julius Boros finished a shot ahead of Arnold Palmer and Bob Charles. Palmer never won a PGA Championship. Guy Boros remembers hearing that the ABC broadcast of that PGA Championship always showed his father from below the brim of his cap — the network didn’t want to show the Amana hat he was wearing. Boros was one of the first players, along with Bob Goalby, to wear the Amana hat. Free appliances, that was the main draw. The times they have changed.

Rees Jones has a photograph from the 1950 U.S. Open at Merion, which he attended with his father, that features Ben Hogan in the foreground, and young Rees behind him. Nobody wore a hat with any sort of brand name on it. Can you imagine Hogan as a walking advertisement?

Rees Jones did a total makeover of the South Course at Torrey Pines, a muni if ever there was one, some years before the first U.S. Open there, in 2008. He made the course harder, longer and more telegenic.

(A disclosure: I’m proud to call Rees a friend. Years ago, he came to a golfy dinner at our home, told stories during the dessert course, and later, in an unnecessary and handwritten thank-you note, said, “and I didn’t mind singing for my supper.”)

Monday night, on Golf Channel, I heard an insightful analysis of the South Course from Justin Leonard, who knew the Torrey Pines course before and after its renovations. It was detailed and minute and surely true. But you could also say, to get down to its essence, that the South Course at Torrey Pines was a big, public oceanfront course before Rees Jones first set foot there in 1999, and it remains so today. That’s the magic of Torrey: It’s an oceanside public course, and the weather there often is beautiful.

Jones has also done a major renovation at Coral Ridge, where Guy Boros logged a lot of rounds as a kid. Coral Ridge is not elite, uptight country-club golf. You could say it’s a version of the American dream. Safe, comfortable — well-ordered. It’s a place to learn golf, play golf, swim, eat, play cards, play tennis, socialize.

“The similarity between the two,” Rees told me recently, “is that they’re both gathering places. At Coral Ridge, or at Torrey Pines, you’ll have people who are there five or six or seven days a week. They eat there, they have a drink, they play. They see their friends. The golf course is their community. It’s a central part of their life.”

Golfers love meeting U.S. Open champions, and they love playing U.S. Open courses.

Rees Jones grew up in the game at Montclair Country Club, in New Jersey. Yogi Berra was there every day. He’d play, eat lunch, play cards, take a shower, go home to Carmen and dinner. Yogi made the money. Carmen invested it. The Yankees used to have a GM named George Weiss. Weiss had a wife named Hazel. Hazel used to say, “I married him for better or worse, but not for lunch.” Golf has been good for many marriages. This week, Rees’ wife, Susan, will join him at Torrey Pines.

They’ll be watching in person. Guy Boros will be watching on TV, from South Florida. Everybody will be curious to see what Phil Mickelson does on the course he first played as a kid. Mickelson, to be absurdly gentle about it, has not been a vocal fan of Rees’ renovation work. That’s OK. It’s a free country. Tiger seems to be just fine with it. Rees is rooting for Phil. How cool would that be, to see Phil win this week?

As for Guy Boros, he couldn’t have been cheering for Phil as Mickelson marched on home at Kiawah last month, but Boros was fine with the result in the end. His father’s record held up for a long time. Rees’ renovation work at Torrey will likely do the same. They’re both second-generation golf people. They know how the game is played.

Michael Bamberger welcomes your comments at Michael.Bamberger@GOLF.com.