How hard is it to win a USGA event at Winged Foot? Check this: On his 72nd hole played in the 1984 U.S. Open at Mamaroneck, N.Y.’s finest, Greg Norman holed a par putt from the Hutchinson River Parkway. When he signed for his 69, his 72-hole total of 276 was four less than par. In the years, hours and minutes prior to Norman’s bomb, not one of the 943 players who preceded him in USGA stroke-play competition at either of Winged Foot’s courses had finished with an under-par aggregate regulation score. In other words, no player in the 1929 U.S. Open, 1954 U.S. Women’s Open, 1959 U.S. Open, 1972 U.S. Women’s Open, 1974 U.S Open or 1980 U.S. Senior Open had beaten par. For the sake of comparison, in the six U.S. Opens played at Oakmont between 1927 and 1983, par had been bettered in four (1953, 1962, 1973, 1983).

Moments after Norman finished, Fuzzy Zoeller also parred the 18th at Winged Foot West to tie Norman. In the Monday playoff, Norman shot 75 (+5) and Zoeller carded 67. If you throw in the 156 players who vied for the 2006 U.S. Open, none of whom recorded an under-par total, it means that, strictly speaking, Zoeller is alone among 1,103 players to have competed in a USGA stroke-play event at Winged Foot and utterly and completely finished under par.

In short, playing a USGA championship setup at Winged Foot is like sitting in a tub full of fire ants for four days — even if you come out on top, the bite marks are still visible. Here’s a list of the legends who have survived Mercury’s poison.

Bobby Jones, 1929 U.S. Open

WEST COURSE, 294, +6, PLAYOFF WITH AL ESPINOSA

You can still make a solid case that Jones is the GOAT. He won four U.S. Opens and three British Opens over the course of eight tournament seasons (1923–1930), a torrid stretch neither Jack Nicklaus nor Tiger Woods could match in later years. And he lost a playoff for the 1925 U.S. Open to (Groundskeeper) Willie Macfarlane after calling a penalty on himself in the first round. In ’29, Jones very nearly pulled a Mickelson 77 years before Lefty did. Jones was six strokes clear of Espinosa with only six holes to play. As he stood in a greenside bunker at the final hole, Jones “was on the verge of the worst catastrophe any U.S. Open had ever known,” wrote Grantland Rice, and faced an up-and-down from a bunker just to tie Espinosa. According to eyewitness Rice, the putt was 12 to 14 feet and had “at least a foot and a half” of “dip or break in the green that had to be judged.” Jones made the putt and won the 36-hole playoff the next day by a margin of 23 strokes. Espinosa took home the winner’s check for $1,000 — not the last time a non-winner outearned a champ at Winged Foot. The following year, Jones “stormed the impregnable quadrilateral.”

Dick Chapman, 1940 U.S. Amateur

WEST COURSE, 11 & 9 VS. W.B. McCULLOUGH

Two dimes and a nickel would have gotten you a souvenir program, the cover illustration of which featured the Winged Foot clubhouse atop a globe showing the Americas and the logo of Ripley’s Believe It or Not! Warrington McCullough probably felt as if the clubhouse had plopped down on him rather than landing on Canada after losing 11&9 to Chapman in the 36-hole final. But Ol’ W.B. was no chump — he beat four Walker Cup players (two of whom were recent past winners of the U.S. Amateur) to reach the final match against fellow gentlemen golfer Chapman, a Winged Foot member. Chapman was a typical bon vivant with the exception of his intense interest in swing mechanics. “The affluent Chapman studied his hobby as if it were his profession,” wrote Time magazine upon his death in 1978, also referring to him as “the Ben Hogan of amateur golf.” According to one legend, so evident was Chapman’s obsession that Hogan shared The Secret with him years before it was revealed in Life magazine. Chapman really did know his way around the divot factory — he won the 1951 British Amateur, the ’58 North and South, a Canadian Amateur, a pair of French Ams and one Italian Amateur. Chapman also played in 19 Masters Tournaments (an amateur record co-held with Charlie Coe, whom he dispatched in the final of the ’51 British Amateur), making the cut in 13 (11th in 1954 was his best finish), and, in 1954 at Baltusrol, he made the fifth hole in one in U.S. Open history. Also, if you ever played an event that used the Chapman format, it was developed by our boy, Dick.

Betsy Rawls, 1957 U.S. Women’s Open

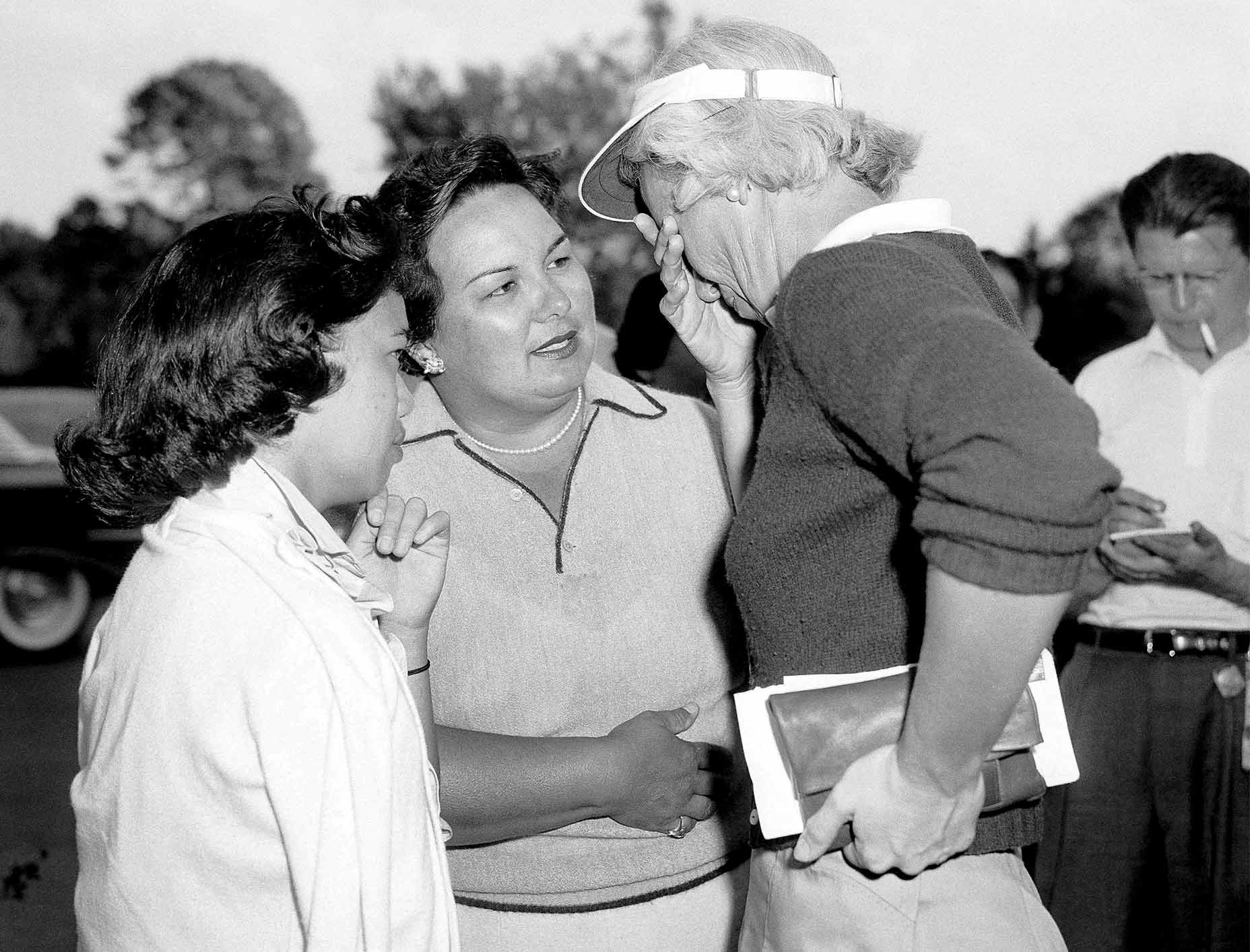

EAST COURSE, 299, +7, BEAT JACKIE PUNG ON A TECHNICALITY

If you look at the U.S. Women’s Open trophy, you won’t see Jackie Pung’s name, but she won the tournament in 1957. In the final round, Pung did something no other player did that week — she broke par, with a round of 72. Then she did something only one other player did that week — she signed a technically inaccurate scorecard, handing the title to Betsy Rawls (who had finished one shot back). Despite their cards reflecting correct total scores, Pung and her fellow competitor Betty Jameson both recorded the incorrect score for each other at the 4th hole, and neither caught the glitch during review. Unlike Roberto De Vicenzo, who infamously missed out on a playoff at the 1968 Masters when he did something similar, Pung would have been the outright champion. Covering the event for Sports Illustrated, Herbert Warren Wind candidly explained why even golf law is sometimes an ass. “The shocking news… filled everyone with a personal sense of impotent anger and with compassion for the victim of so important a ruling based on so insignificant a technicality. Had the disqualification been waived, the rules of golf would not have been weakened, and the spirit of golf more honestly served.” The outcome was a double bummer for Pung, who had come close to winning the Open in 1953, before losing a playoff to Rawls. Upon realizing she’d lost out, Pung fled the club grounds with her young daughter — only to return shortly later for the trophy presentation to Rawls. When it came time for Pung to speak, she said, “Winning the Open is the greatest thing in golf. I have come close before. This time I thought I’d won, but I didn’t. Golf is played by rules and I broke a rule. I’ve learned a lesson, and I have two broad shoulders…” While Pung would assuredly have rather had the trophy, she proved such a good sport through the ordeal that Winged Foot members and USGA officials passed the hat and collected $3,000 for her — $1,200 more than Rawls’ winner’s check. In 1998, Winged Foot members invited Pung to join them in celebrating the club’s 75th anniversary — she was born the same year the club was founded (1921). Pung accepted and walked the East Course one evening, quietly replaying every stroke from her round of 72 in 1957.

Billy Casper, 1959 U.S. Open

WEST COURSE, 282, +2

If you love watching a fella get up and down, this was the tournament for you. Over the course of his career, Casper racked up 51 PGA Tour wins, including two U.S. Opens and a PGA Championship. Clearly, he could swing that thing — but you wouldn’t have known it were you at Winged Foot for the ’59 Open. According to Dan Jenkins, “It’s doubtful any golfer ever played more poorly from tee to green and still managed to win a major championship.” Over 72 holes, Casper was in 21 bunkers and missed nearly a third of the fairways from the tee. In the final round alone (during which Jenkins wrote “he looked like he was shooting 91”), Casper drove it into the rough nine times, found sand seven times and recorded only six GIR. (He carded 74.) If you’re unfamiliar with Casper, you may have deduced by now that he was magic with the putter (in his case, a mallet-head used with a “pop” stroke that was common at that time) — and he was: He putted only 114 times over 72 holes.

Susie Berning, 1972 U.S. Women’s Open

EAST COURSE, 299, +11

“Mrs. Berning Recaptures U.S. Open Golf Crown” was a headline in The New York Times indicating the paper of record wasn’t quite in step with the burgeoning women’s rights movement of the day (not to mention the same story referring to Berning as a “30-year-old matron”). Berning was a big-game player — she won three U.S. Women’s Opens and a Western Open when that ranked as a major. She won 11 total events in her career, establishing a record not entirely different from Hale Irwin and his three U.S. Open, 20-win total on the PGA Tour. After a 79 in the first round at Winged Foot East, it seemed unlikely Berning would win her second Open that week, but the scores ran high across the board — a foreshadowing of Opens to come at the club. Among three players who finished one shot behind Berning was Judy Rankin, marking her best ever shot at winning the Open.

Hale Irwin, 1974 U.S. Open

WEST COURSE, 287, +7

After two rounds, Irwin was tied for the lead at +3 with Arnold Palmer, Raymond Floyd and Gary Player, three players who, by Irwin’s own admission, probably didn’t know who he was. The ’74 Open remains Exhibit A in what happens when the USGA is overzealous with course setup, living in infamy even today as the “Massacre at Winged Foot.” Many players felt that with rough higher than Snoop Dogg and greens harder than a frozen Snickers the USGA was exacting revenge for Johnny Miller’s closing 63 at Oakmont the previous year. The guys in ties denied it — but either way, the quips were better than the golf. Tom Watson held the lead going into Sunday’s final round, and Irwin snatched it from him by holing a longish birdie at the 9th hole to get to +5. As the ball went in, Irwin jogged briskly away from the hole — an early version of his high-fiving-fan runs 16 years later when he won his third U.S. Open. For the week, only Irwin and Forrest Fezler (+9) recorded scores of less than +10. When Jack Nicklaus, who finished T-10 at +14, was asked to describe the course setup, he said, “The last 18 holes are very difficult.”

Roberto De Vicenzo, 1980 U.S. Senior Open

EAST COURSE, 285, +1

“What a stupid I am,” the Argentine De Vicenzo said after a misfire in the scorer’s tent cost him his chance to win the ’68 Masters. For both De Vicenzo and Jackie Pung, it was perhaps a bit of karmic justice from the universe that he won at Winged Foot East in the inaugural U.S. Senior Open. Players had to be at least 55 for the first Senior Prom — the age was dropped to 50 the following year. It’s a shame American golf fans only remember De Vicenzo for the scorecard debacle — he won the 1967 British Open, six PGA Tour events, nine European Tour events, 131 Argentina Tour events and 62 other assorted Opens and such in South America. So determined was he to be known as a world-class player that in 1949 he traveled from Argentina to the British Open on a cargo ship — a 17-day journey. He died just 10 weeks after Pung did, in 2017, at 94.

Fuzzy Zoeller, 1984 U.S. Open

WEST COURSE, 276, –4, PLAYOFF WITH GREG NORMAN

For a fleeting moment after Norman made his bomb at the 18th on Sunday, Zoeller, who was standing in the fairway watching, thought the putt was for birdie. He hadn’t seen the Shark’s approach shot, which had landed in the spectator stands. Zoeller waved his dirty white bag towel in mock surrender before a USGA official told him Norman had merely made a miracle par. The towel bit made for great TV. Zoeller dusted Norman easily in the playoff, the first of what seemed a million major heartbreaks for the Aussie superstar. From a historical perspective, perhaps the most significant outcome was that in consecutive Opens at Winged Foot, Forrest Fezler and Fuzzy Zoeller finished second and first.

Davis Love III, 1997 PGA Championship

WEST COURSE, 269, –11

Every event of global golf significance at Winged Foot has been a USGA event with the exception of this one. Love’s victory was short on drama but long on emotion. Over the years there have been a handful of PGA Championship course setups that were borderline USGA-grade sadistic, but this wasn’t one of them. That doesn’t take away from the fact that Love posted 66 in three of his four rounds, including Sunday. He also separated from the field in Secretariat-type fashion, with only two players staying within 10 strokes of him. The drama came at the end of a rainy day, when a massive and persistent rainbow emerged to frame the scene as Love walked toward the final green with his brother Mark on the bag and he holed a last birdie. It was a popular sentiment of those watching on TV and in attendance to think of it as a spiritual nod from Love’s father, the widely beloved Davis Love Jr., a long-time PGA member, Tour player and highly regarded teacher who died in a plane accident in 1988. Fun fact: This was the last major won by any player using a persimmon driver.

Ryan Moore, 2004 U.S. Amateur

WEST COURSE, 2 UP OVER LUKE LIST

Moore birdied the final four in the 36-hole final to close a come-from-behind win, and become the first player to win the U.S. Am and Amateur Public Links in the same year. And brother, what a year — Moore also won the NCAA individual championship and the Western Amateur. Winged Foot West bulked up to 7,266 yards for the final — the first time the venerable track went over 7K for a championship and officially two yards longer than it played two years later for the Open.

Geoff Ogilvy, 2006 U.S. Open

WEST COURSE, 285, +5

There is much more on this horror show elsewhere in this issue, but in short: Ogilvy chipped in for par on the 17th and made a sexy up-and-down at 18, while Phil Mickelson and Colin Montgomerie both really bollixed things up and finished second at the U.S. Open for the 800th time in both their careers. Fun fact: Ogilvy became the second player to win the Open with a first name that ended in twin consonants. Scott Simpson, 1987, was first and, intriguingly, Webb Simpson was third in that exclusive club in 2012. Lloyd Mangrum, Open winner class of ’46, is the only alum whose first name starts with twin consonants.