In July 2020, in southwest Ohio, a recent high school graduate named Patrick Rukundo received a phone call with an unexpected offer. It came from the golf coach at a local college. The coach was dangling a scholarship, a golden deal to join the team that fall.

As a standout student from a humble background, Patrick wasted little time accepting. All the paperwork was signed. Everything was set, with one exception.

It was now on Patrick to learn the game.

“I knew the word ‘golf’ and I had heard of Tiger Woods,” he says. “But I had never seen a golf course or watched any golf. I had to look at videos to see how it was done.”

Golf takes those who play it on improbable journeys. But few paths are more unlikely than the one Patrick took to picking up a club. The seventh of nine children, he was born and raised in a refugee camp in Rwanda, in eastern Africa, where his parents settled after fleeing civil war in their native Congo. Patrick’s childhood home was a low-slung hovel, with no electricity or running water.

“We didn’t have a lot, but we were happy,” he says.

In 2016, when he was 16, his family earned asylum and moved to Baltimore. Patrick knew three languages, but not English. To ease the transition, he dropped back a year in high school, enrolling with his younger brother as a freshman.

The other way he acclimated was through sports.

A natural athlete, Patrick had grown up playing soccer. He soon became a stalwart on his school’s starting 11. He was making friends and fitting in. His family, though, was barely getting by, with his father working in waste management and his mother employed at a meat-packing plant. In 2018, seeking lower costs and safer streets, they moved again, this time to Ohio.

At Dunbar High School, in Dayton, Patrick stayed productive in the classroom and beyond. In Baltimore, he had tried his hand at volleyball and tennis. Now he tried his feet at football, kicking field goals and extra points.

“I was too scared to be the punter,” he says.

He also took up track. But soccer, as he saw it, was his best ticket to a college education, if only Dunbar’s soccer team drew more attention.

“We weren’t very good, so nobody really noticed,” Patrick says.

At graduation, Patrick had a straight-A transcript and scholarship offers from several colleges in Ohio and Indiana. But they weren’t full rides and not all the schools were close to home. Both factors were deal-breakers.

“I was taking my time, trying to make a good choice,” Patrick says.

That’s when his phone rang. It was William Ware, the newly minted golf coach at Wilberforce University, just down the road, the country’s oldest private, historically Black university.

The Wilberforce golf program had a story of its own. Founded in the 1950s, it was robust for its day. But over the decades, it had faltered, then folded. In 2015, the school had brought it back, but the revived team was only a team in the loosest sense, with a fill-in coach and a roster populated by student-athletes from other sports. In 2018, the program was suspended by its own conference for being short on players — a low point that doubled as a wake-up call.

Patrick’s phone rang. It was William Ware, the newly minted golf coach at Wilberforce University.

“We realized that we were missing a huge opportunity with golf,” says Derek Williams, who came aboard that same year as the school’s athletic director. “We had a big alumni base that loved the game, and it was something that could provide a lot of young people with a path to college. It was time we went all in.”

The job of recruiting fell to Ware, a former track star at Dunbar (and, later, the University of Cincinnati) who didn’t take up golf until he was in his mid-20s, when he was introduced to it through his career in banking. Ware was almost 40 now, and though he’d gotten good enough to give lessons on the side at a local public course, he had no experience with the task at hand: starting a college team from scratch.

The big reboot kicked off in the summer of 2020. With just months to spare before the season, Ware worked his contacts, trying to drum up names. Among the calls he made was to his former Dunbar track coach, Sydney Booker, who was still in that role at the school. Booker mentioned Patrick as a primo candidate, a diligent kid with excellent hand-eye and an even better head.

“So, Coach William contacts me and tells me he can give me a scholarship,” Patrick says. “And I thought, OK, maybe golf is now my sport.”

Wilberforce University takes its name from the 18th-century abolitionist William Wilberforce, whose notable quotes include this line: “We are too young to realize that certain things are impossible…So we will do them, anyway.”

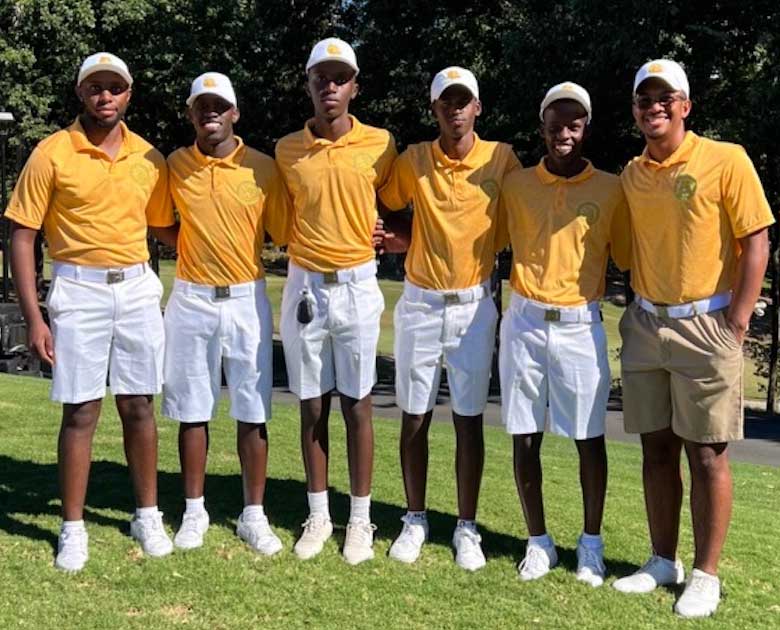

This could have been the motto of the fledgling program. Ware’s team had no uniforms, no practice grounds, no home course. But at least it had the minimum allotment of players, four altogether. That was partly thanks to Patrick, who had helped Ware round up more recruits.

The three others who signed on were Yves Yuyishime (Patrick’s younger brother); Emmanuel Nshimiyimana (who’d grown up with Patrick in the refugee camp) and Ngabo Rubibi, who was also from east Africa. He and Patrick had met a few months before.

When they first convened as a group on campus, no member of the team had ever struck a shot that counted toward a score.

This was not a squad fit for competition. Nor was their coach in any mood to rush. Covid was raging. Travel was restricted. For the first six months, the only trips the players made were to a nearby practice center, the Bairs Den, whose owner, Brian Bairs, gave the team discounted range balls.

The learning curve was grinding. At the outset, Patrick concedes, he didn’t find it fun.

“I had a soccer stance with my hands separated on the club, and I kept missing the ball because I was trying to kill it,” he says. “One day, I would think that I had figured something out, but then the next day I was hitting it two inches again.”

The game meted out its punishments, but Patrick persevered, making progress — and not only on the course.

By spring, though, his fundamentals had improved. So had his options. Ware had arranged access for the team at two local courses: Beavercreek Golf Club and Miami Valley Golf Club, the latter a private Donald Ross design that played host to the 1957 PGA Championship.

Getting out for real provided Patrick fresh perspective.

“Hitting shots on a course is more beautiful and interesting,” he says. “You can see the challenge and the work you need to do. It gave me a different vision of golf.”

Another full year passed before Wilberforce competed in its first official tournament, in a meeting of teams from historically Black colleges. It was the spring of 2022, at Summer Grove Golf Club, in Georgia. Patrick played one round and shot 126, his opening drive a topper that helped set the tone.

“Those first holes were unbelievable because I was playing a zigzag game, left to right to left, and taking three putts or more,” he says. “Everything wasn’t working. Maybe it was the pressure. But I also know my swing was bad.”

More tournaments followed, and you can probably guess: The game meted out its punishments, but Patrick persevered, making progress — and not only on the course. He was building confidence, broadening horizons. He and his teammates attended the Memorial, at Muirfield Village, to watch the world’s best players. Michael Jordan invited them to visit his private club in Florida, and the Wilberforce crew took him up on the offer.

“An amazing trip,” says Patrick, though he missed out on the chance to meet His Airness himself.

In Patrick’s final round of the spring season, he putted out on 18 for a 99, the first player on the team to break 100. Then summer arrived, and, with it, another opportunity. Patrick had an offer from the United States Golf Association.

One of golf’s big problems is it hasn’t often looked much like the world around it. It’s still a long way off. But there’s a growing effort to make things right. In the fall of 2020, shortly after Wilberforce rekindled its program, the PGA Tour gifted the school with $100,000. Equipment makers provided clubs. Internships started taking shape.

In 2021, Patrick and his teammates all landed paid posts with the Miami Valley Golf Association, handling a range of data-driven office jobs. Patrick stood out to the point that the USGA upped the ante, granting him a P.J. Boatwright Jr. internship for the summer of 2022. Since its birth in 1991, the Boatwright program has invested more than $32 million to help prepare young people for careers in golf. In 2022 alone, $1.7 million went toward more than 125 internships at the governing body’s Allied Golf Associations across the country.

In his Boatwright role, Patrick moved beyond the office to more interactive aspects of the industry. He helped with handicapping and tournament setups, cut his teeth in marketing and communications, pitched in on junior programs.

“Patrick is an example of the power of positive thinking and moving forward,” says Steve Jurick, executive director of the Miami Valley Golf Association. “He’ll do whatever is asked of him. He takes on everything 100 percent. He is a role model and essential to the story of what our game should look like in the years ahead.”

A life in golf doesn’t sound half-bad to Patrick, but he hasn’t settled on a career. He’s a college junior now, with all his costs covered (when the school saw his grades, it offered Patrick a full academic ride, so the golf scholarship could go to someone else), majoring in electrical engineering, a field he regards as a gratifying bookend to his upbringing.

“When you grow up somewhere that you don’t have electricity, it is good to think of helping bring power to some people,” he says. “In that way, maybe I can give back to the world.”

Meanwhile, he’s still working on his game, in a program that keeps improving. In the first tournament of this fall’s season, Patrick shot an 86, only to be bested by a teammate, who signed for a 79. Since its threadbare start in 2020, the Wilberforce roster has swelled to seven players, two of whom took up the game in high school.

Experience matters. Not much in golf happens overnight. Building a college program is a Catch-22: It takes resources to attract talent, and the other way around. As coach, William Ware has adopted the long view.

“At first, it was tough to get anyone to come to Wilberforce,” he says. “I had no golfers. I had no facility. I didn’t have a lot that I could offer.” Enough momentum has since swelled behind him that the school now has a fledgling women’s golf program, too.

“My vision is be competitive enough where the best golfers in Ohio want to come play for us,” Ware says.

This past week, Wilberforce men’s squad wrapped up its 2022 campaign, at the Mid-South Conference Fall Classic, in Kentucky. On the scorecard, it wasn’t Patrick’s finest showing. He shot in the low-90s. But numbers are no measure of what really matters.

“Maybe it’s because where I grew up, but when I’m playing golf, I’m trying to do my best but it’s not everything I’m thinking,” Patrick says. “I know I’m going to hit some bad shots, and that’s OK. At the end of the day, that doesn’t tell people who you are.”