This content was first published in Golf Journal, a quarterly print publication exclusively for USGA Members. To be among the first to receive Golf Journal and to learn how you can ensure a strong future for the game, become a USGA Member today.

***

“A great many players are averse to using forward tees…but it seems a great deal more enjoyment could be had if golfers used the tee that really suited their game.”

“If the distance gotten with the ball continues to increase, it will be necessary to go to 7,500- and even 8,000-yard courses, and more yards means more money for the golfer to shell out.”

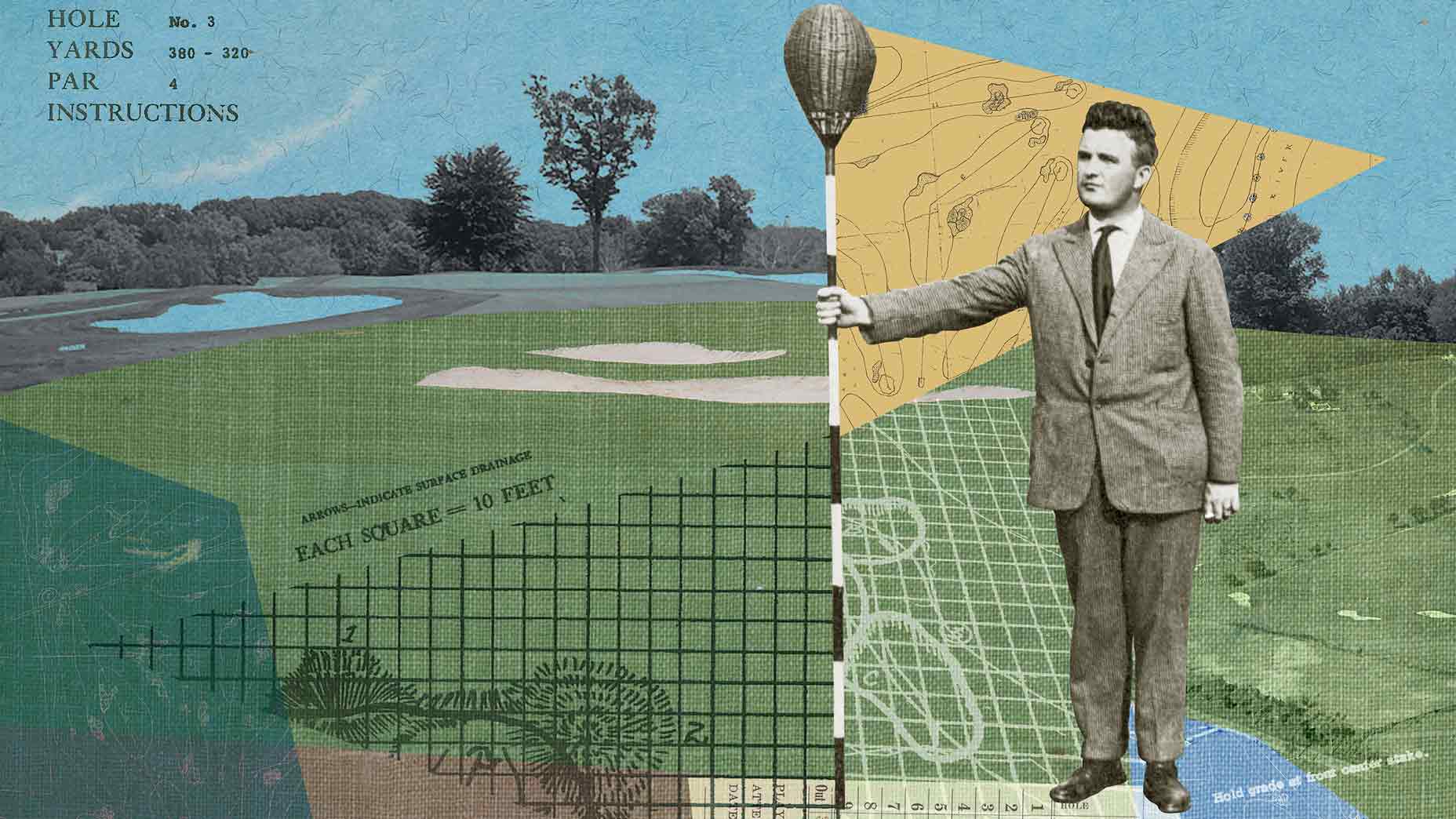

The course architect quoted here is undoubtedly a steward of the game, judging by his commentary on the golf ball and the importance of playing from the proper tees. Now consider that those writings appeared in the USGA’s Green Section Record nearly a century ago, penned by William Flynn in 1927.

Flynn is among the most accomplished — and least celebrated — architects of the game’s Golden Age in the United States. Donald Ross, Charles Blair Macdonald, A.W. Tillinghast and Alister MacKenzie all spring quickly to mind when one considers the classic designs of the 1920s and 1930s; although that quartet was talented and prolific, Flynn’s courses match or exceed their USGA championship pedigrees.

Flynn, a Boston native who went on to become a member of the so-called Philadelphia School of Design (which also included Tillinghast, George C. Thomas Jr., George Crump and Hugh Wilson), will earn another notch in his USGA resume in late May, when Lancaster (Pa.) Country Club hosts the U.S. Women’s Open for the second time in nine years. And why not? The 2015 edition of the championship at Lancaster produced a stirring back-nine charge by winner In Gee Chun and shattered championship attendance marks.

Whether or not the massive crowds carry over to this year, one long-standing effect of Chun’s unexpected victory is the close relationship she has forged with the club — a foundation in her name provides college scholarships to caddies and family members of club staff, thanks in large part to several return trips by Chun for fundraising events.

The course that Chun and 155 fellow competitors take on will feature fewer trees but a dozen more bunkers than in 2015, thanks to continued restoration efforts by architects Ron Forse and Jim Nagle.

“Lancaster is a magnificent golf course with fantastic putting green complexes,” said John Bodenhamer, the chief championships officer for the USGA. “If you were to put this course near New York City or Boston, it would get a lot more attention. Flynn’s courses such as Lancaster stand the test of time; it’s a shotmaker’s course, and that never goes out of style.”

Courses that Flynn designed or had a hand in producing are solidly among the game’s cathedrals: Merion, Pine Valley, Shinnecock Hills, The Country Club, Cherry Hills. Others are perhaps less known, but the USGA keeps returning to places such as The Cascades Course at The Homestead in Hot Springs, Va., for the enduring qualities that Bodenhamer cites. The Cascades will host two USGA championships, its ninth and 10th, in the next five years.

How the USGA is helping golf courses save almost $2 billion annuallyBy: Matt Pringle

“For Flynn and architects of his time, strategy was paramount,” Bodenhamer said. “It wasn’t about being brutally long, or placing bunkers so you had to drive it into a 25-yard corridor; it was about giving you choices. His use of short grass around the greens and the way he placed greens on the land is brilliant. You can miss your target by just a little bit and you’re running 20 or 30 yards away from the putting surface.”

Bodenhamer cites the par-4 8th hole at Shinnecock Hills, a renowned Flynn design on Long Island that will host its fifth U.S. Open in 2026, as a prime example of his strategy.

“When we played there in 2018, that fairway was 65 yards, the second-widest in U.S. Open history,” Bodenhamer said. “But if you hit your tee shot on the right side of the fairway and the hole is on the right side of the green, you can’t get within 40 feet of the hole. You’ve got to think about the angles and moving the ball a certain way, and Lancaster has a lot of that as well.”

Flynn outpaced most designers of his era in his knowledge of agronomy and course maintenance, having worked for several years helping to build both courses at Merion Golf Club in Ardmore, Pa., starting in 1912. Flynn went on to lead that construction effort and provide design input to Wilson, the architect of the East Course, which has hosted a record 19 USGA events, two more than The Country Club and Oakmont Country Club.

“Flynn worked on the East Course from 1912 to 1934,” said Wayne Morrison, the author of a massive Flynn biography. “A lot of that was with Hugh Wilson, but after Wilson died in 1925, Flynn and his associate, Howard Toomey, continued to work on and make changes to the East Course in preparation for multiple USGA championships.”

Lancaster Country Club was founded in 1900, but by 1919, golf’s popularity required that its nine-hole course be updated and expanded to 18 holes. The club more than doubled its acreage from 60 acres to 126, and it hired Flynn to improve upon its offerings. Flynn’s 1917 design of nearby Country Club of Harrisburg and his experience at Merion likely won him the job. The hiring committee noted that Flynn was “the best man in the country on constructing greens.”

Flynn worked for 10 months at Lancaster at a rate of $44.92 per month, and he continued to serve as its consulting architect for the rest of his life. The cost for the new nine holes and the remodeling of the existing nine in 1920 came out to just over $61,000.

Because of Lancaster’s proximity to Flynn’s home base in Philadelphia, he visited the course many times, starting with his original efforts there in 1920 (at age 29), and continuing until his death in 1944.

“Lancaster is an interesting Flynn case study, because he worked on it for so long,” Morrison said. “With the acquisition of new land, and the continued evolution of the golf ball and clubs, he kept bringing it up to date. Not to mention that, while Ross was working on upwards of 20 or more courses in a year, Flynn was doing two or three a year. He spent a lot more time on-site and got to know the property.”

One aspect of Flynn designs that has helped keep them relevant decades after their debuts is that several of them are par 70s.

Tiger Woods honored with USGA’s most prestigious awardBy: Kevin Cunningham

“If you look at Flynn’s portfolio and his influences, many of those courses have only two par 5s: Merion, Pine Valley, Huntington Valley, Shinnecock,” Morrison noted. “It follows an interesting pattern, and I think it’s one of the reasons that these courses hold up in terms of championship scoring. Perhaps he considered two par 5s enough, combined with various long and short par 4s where someone who can execute all the shot shapes and trajectories would have an advantage. It takes luck out of the equation.”

Flynn’s background in turfgrass research and course construction at Merion included developing test plots for new seeds and maintenance practices. This approach was noted by “Joe Bunker,” likely the nom de plume of Tillinghast, in a 1916 Philadelphia Inquirer article about Merion: “Its greenkeeper William S. Flynn … directs a big workforce, and they have a system perfected whereby they can tell just how much it costs per hour to water or cut a green, dig a pit, construct a mound or cut the fairway or rough.”

There are about 50 Flynn courses still in existence out of more than 70 that he designed, a far cry from the roughly 400 attributed to Ross, or the more than 250 credited to Tillinghast. Flynn is venerated for his course routings, which no doubt benefited from his time spent on the ground. As Flynn described his process, “It quite frequently happens that the architect will select perhaps 30 or 40 different green sites on a property when his ultimate job is to secure only 18.”

Morrison described Flynn as a quick study, citing his aptitude in producing a highly regarded layout for the Cascades Course at The Homestead over the course of one day in 1923, after several of his contemporaries had struggled and failed to come up with a suitable routing.

The routing at Lancaster is among Flynn’s finest, and he updated it with four new holes (Nos. 3-6) in the 1940s after the club purchased land across the Conestoga River. The river comes into play most notably for the U.S. Women’s Open on No. 7, where players must decide how much of the water to attempt to cross with their tee shot on the par-5 hole that played at 482 yards in 2015.

Morrison describes the 346-yard, par-4 4th hole as one of the iconic holes in American golf. “There are few holes like it,” he said. “The creek plays down the right side of the low-lying fairway, and then you’re faced with an uphill approach over the water to a shallow, raised green that parallels the fairway.”

Other noteworthy holes include the demanding uphill finishing par 4s on each side – the 421-yard ninth and the 437-yard 18th, both of which yielded barely more than 20 birdies for the entire week in 2015. The most daunting stretch in 2015 was Nos. 8-12, which played as five of the six toughest holes for the week. One respite came on the par-4 16th hole on Sunday, when the tee was moved up to 235 yards from the hole for Round 4. That led to players attempting to drive the green and three eagles being logged, including one by Amy Yang, who finished one stroke behind Chun.

Bodenhamer is most looking forward to the action on the downhill, par-3 12th hole, which played 169 yards in 2015.

“It’s a magical hole, and I think it could be where the Open is won or lost,” he said. “You have to be so precise, to a small, severe green. There will be a lot of 8-irons and 9-irons, and if you put too much spin on it, your ball can go back into the creek. You can make anything from birdie to triple bogey in the blink of an eye.”

Shannon Rouillard, the USGA’s championship director of the U.S. Women’s Open since 2017, who helped with course setup in 2015, agrees.

“The par 3s stand out at Lancaster,” Rouillard said. “There’s so much movement to these greens; they’re going to test players in a variety of ways. Add in par 4s like No. 4, and it’s going to provide a complete test of golf.”

Mix in some of the atmosphere from 2015 that produced crowd roars that LPGA veteran Morgan Pressel said gave her chills, and the elements are there for another special week in Pennsylvania Dutch Country.

“Lancaster wasn’t very familiar to the golf community in 2015, but it’s a tough, classic course,” Rouillard said. “And I’ve said it many times since 2015, the surrounding community provided the kind of support that the U.S. Women’s Open should have every year.”

Ron Driscoll is the USGA’s senior manager of content and Golf Journal senior editor.