MAMARONECK, N.Y. — The hardest thing in golf, when you’re trying to win your first major, is getting to the house. You might play your bottom off for 54 holes or 63 or 71, but to win you have to finish and finishing is difficult. As Jordan Spieth once said so tellingly, “Thoughts creep in.”

We all remember that Sunday at Augusta in 2011, when Rory McIlroy got out of bed with a four-shot lead and shot 80. Some of us remember Tom Watson’s 79, Sunday at Winged Foot in the 1974 Open, when he was the third-round leader by a shot. Most guys blow a major before they win one.

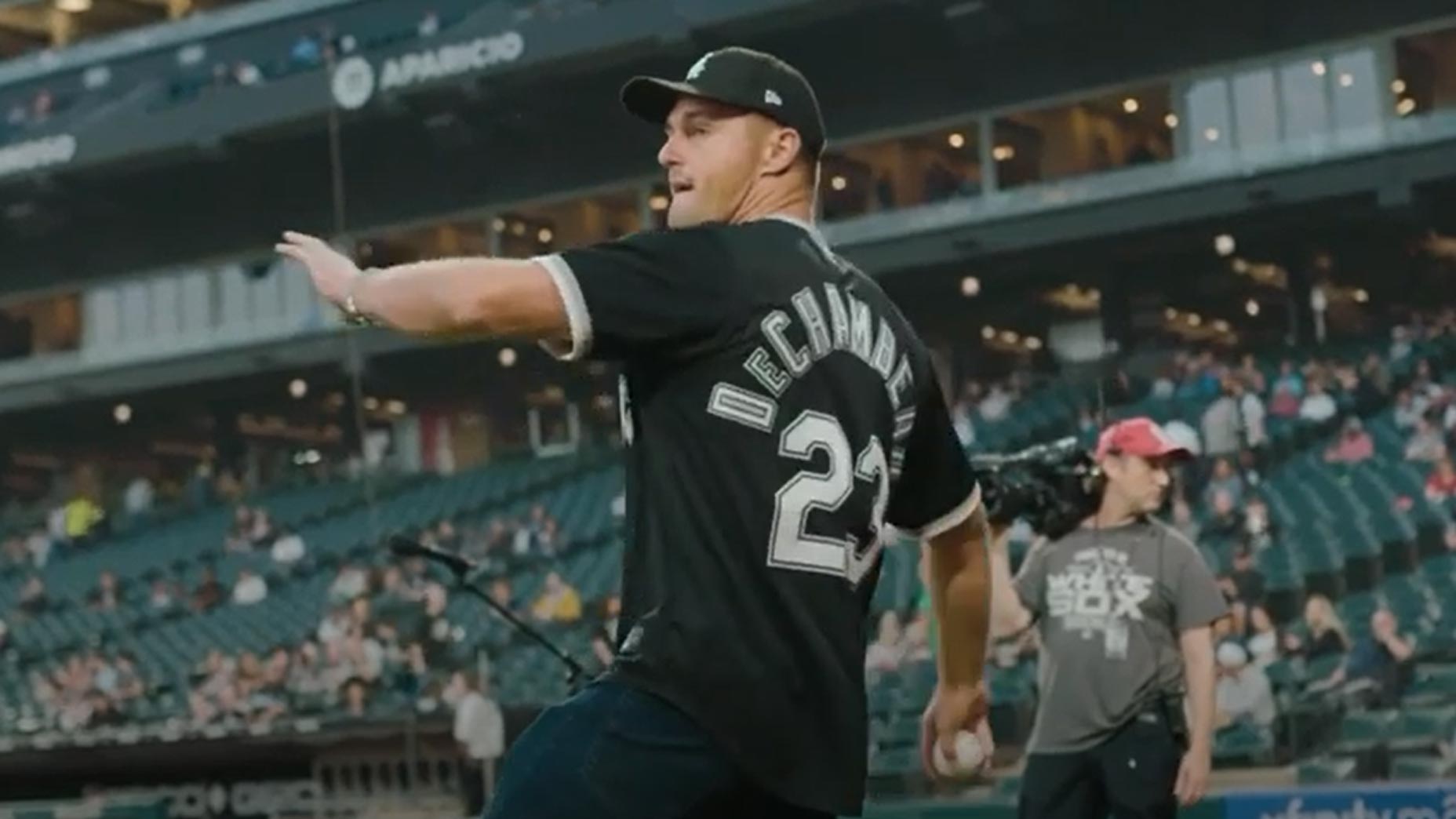

Enter Bryson DeChambeau: Truly contending for the first time in a major, he was in complete control. Of himself.

Do you love his swing as you do Rory’s and Watson’s? Likely not.

Are you fascinated by his life story, as you are Tiger’s? Unlikely.

Would you trade body types with him as you might with Dustin Johnson? Probably not.

DeChambeau, your new U.S. Open champion, does not care, and why should he? Think about the mental strength that requires, to do everything your own way, different from every other card-carrying member of the PGA Tour, and not care what anyone thinks or says.

That’s why this guy opened (69 and 68), middled (70) and, most spectacularly, closed (67!). He won by six. That’s not supposed to happen, in this post-Tiger age of parity.

DeChambeau’s Sunday 67, a flawless three-under card on the West Course at Winged Foot, one of the hardest courses in the world, came on a Sunday when the stroke average was 74.9. It deserves to go down as one the best closing rounds in any major in the modern era.

For purposes of this discussion, we’ll begin the modern era on the last day of the 1948 U.S. Open at Riviera, when Ben Hogan, one of DeChambeau’s heroes, shot a final-round 68 and won the first of his four U.S. Opens. (Hogan was an original. Also a bantamweight and a smoker.) DeChambeau’s 67 is right up there with Jerry Pate’s closing 68 at the 1976 U.S. Open. Pate, like DeChambeau, won both the U.S. Amateur and the U.S. Open. Others in the modern era who have done the same are Arnold, Jack, Gene Littler and Tiger. (Hogan, by the way, never really got Palmer’s whole bash-and-find thing. They both survived.) DeChambeau, who is 27, will wind up in the World Golf Hall of Fame with those gents. He has seven wins. Let’s see what the next 20 years bring. He could win more tournaments. He could win another major. Collin Morikawa could, too.

He won by six. That’s not supposed to happen, in this post-Tiger age of parity.

DeChambeau plans to gain 15 or so more pounds between now and the Masters, in mid-November. (Morikawa won’t.) He might have a driver there that is three inches longer than his current model. He’s not making changes because he’s looking for something to do. He’s redefining how to think about his game, much as Hogan did. It’s no wonder that Phil Mickelson says that DeChambeau is the most interesting thinker in golf.

Everybody likes praise, but DeChambeau, you can tell, does not turn to others for affirmation. He’s never shown that he really cares what anyone else thinks. (Let’s bring in Brooks Koepka for some play-by-play.) Hence, B.A.D.’s tree-trunk putter grip, his single-length irons, his robotic straight-armed putting stroke. Hence, his Hogan cap (who else is wearing one?), his 8 p.m. alone-in-the-dark driving-range session Saturday night, his two-minute analysis to pull a club on the short par-3 13th. About 210 yards on Sunday and, when all the math was done, a 7-iron for him.

The man — along with his family and “team” — is on his own private Idaho. Life is good there.

In his isolation chamber on Sunday, DeChambeau didn’t really trail Matthew Wolff by two at the start, and he didn’t really take a one-shot lead at the 5th hole, as they played in the day’s final twosome. He was, as per usual, doing his own thing. He knew if he did his thing, the universe would unfold, as it should. Dude’s 230 pounds of pure Zen.

By Nov. 12, at the first round of the Masters, there will be more of the same. Can he drive it into the creek that fronts the green on the par-5 13th hole there? We shall see.

This was the first U.S. Open played without spectators, except for a few strays that were able to find their way to the course under one guise or another. (The press pass!) You might wonder whether that was an advantage for DeChambeau, to play in relative silence. It was not. He’s always playing in relative silence, except for that voice, his own, in his head.

DeChambeau always plays in relative silence, except for that voice, his own, in his head.

You can draw a straight line from Hogan to Nicklaus to Watson to Faldo to Woods to McIlroy to Koepka. You might be tempted to say that John Daly was an outlier, but he wasn’t. Daly in 1991 was, as a swinger of the golf club, a direct descendant of Nicklaus. Rory is a direct descendant of Tiger. But what about DeChambeau? He blends a long-drive contestant’s mentality with Hogan’s ability to truly understand his own swing and Karsten Solheim’s ability to think about the game’s equipment in a novel way. Maybe you’ve been slow to come around on him. You can’t not be impressed by what he did here over four days.

McIlroy, when asked about the guy and his game, said, “The guy — I think [he’s] brilliant. He’s taken advantage of where the game is at the minute. With the way he approaches it, with the arm-lock putting — with everything. I’m not saying that’s right or wrong. He’s just taking advantage of what we have right now.”

And tomorrow will be different.

This is not a criticism: DeChambeau may be too young to really understand what he just did. Tiger, at 27, was like that. He wasn’t when he won the Masters last year, at age 43. This game of golf, especially alongside this thing called life, has a way of growing up all who play it for keeps. DeChambeau is not married. He does not have children. Like Justin Thomas and Matthew Wolff and Collin Morikawa and Viktor Hovland, he’s in a period in his life where he can devote himself to one main thing: getting better at golf. Tiger remembers what that was like. It won’t last forever. Even Hogan found that out.

The winner of this 120th U.S. Open, and its $2.25 million first-place prize, was asked what kind of mental strength he takes, from doing things his own way.

“It’s a lot of validation through science,” he said. “If I hit a 40-footer and it says 10.1 miles per hour on the device, I know that I’ve executed it correctly. If I see the ball go two feet past that 40-foot mark, I know it’s perfect. I know I’ve done everything I can in my brain to make my perception reality. I’m trying to make my perception of what I feel and what I think and turn it into proper reality.”

Maybe you stumbled on the use of the word proper. Or on something else.

The beauty of Bryson’s answer is that it makes sense — to him.

Michael Bamberger welcomes your comments at Michael_Bamberger@GOLF.com.