It’s a gorgeous, ocean-warmed morning in December at the Bald Eagle Golf Club in Point Roberts, Wash. Birds are chirping. The sun is shining. And superintendent Rick Hoole is cutting greens on the back nine. After his final pass on the 14th he stops, admires his perfect cut lines and moves on to the next green. There is no need to dismount his mower and put the flagstick back in the cup, because no golfers will play today. No golfers played yesterday, either. In fact, no golfers have played for seven months. And, sadly, as it stands, no golfers will play for months to come.

Unlike many bursting-at-the-seams facilities in the golf world, Bald Eagle is eerily quiet. A ghost course. Other than a few volunteers who occasionally come out to pull a few weeds or sit on a rough mower, Hoole has the place to himself. His entire crew has been laid off. The clubhouse is locked. The flagsticks and tee markers have been put in storage. It’s been that way ever since Covid-19 hit back in March.

We have a grocery store. A couple of gas stations. One bar that closes early. And that’s about it. Oh, and we used to have a real golf course with flagsticks.

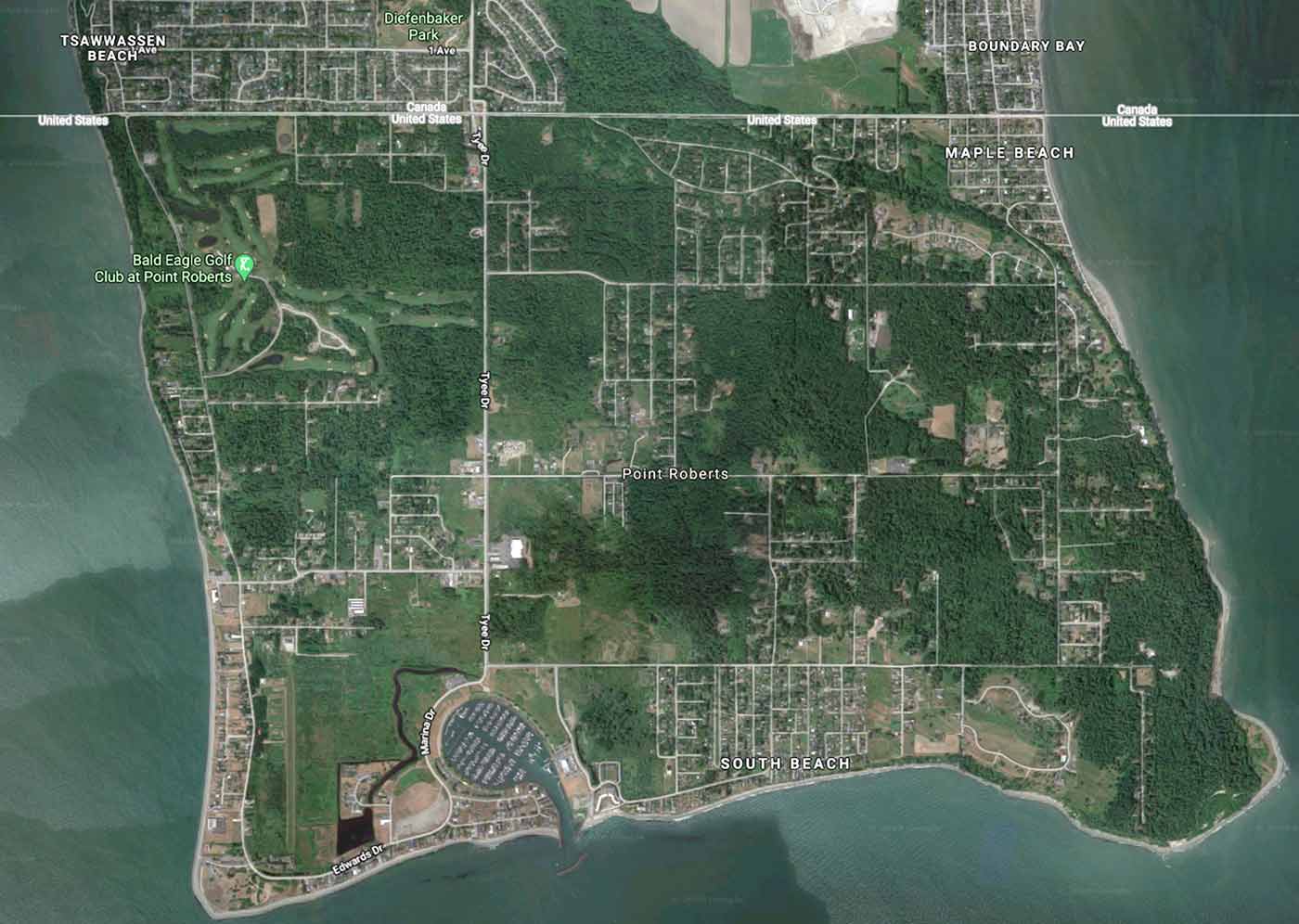

The golfers, stuck on the other side of the border in Canada, can’t get to Point Roberts. Nor can U.S. citizens who reside in “greater” Washington State. The only way for them to drive to Point Roberts is by traveling 25 miles through Canada. And, because the border closed to non-essential travel, this is an impossibility. So Hoole is simply on a “maintain to keep the course alive” mandate; the bare minimum of maintenance standards to ensure the course isn’t entirely reclaimed by moss and mushrooms, ferns and fir.

“It’s like we’re inmates in a 4.7-square-mile prison,” says Hoole, somewhat tongue-in-cheek.

The history of Point Roberts — and why this little parcel of land at the southern tip of the Tsawwassen Peninsula belongs to the United States (and not Canada) — goes back to the Oregon Treaty, which was signed in 1846. In simple terms, this agreement between the United States and Great Britain (Canada was not yet a country) stated that everything south of the 49th parallel would belong to the United States. And, because Point Roberts lies south of the 49th, presto, you have U.S. Territory. Technically, from a geopolitical standpoint, Point Roberts is termed a “pene-enclave,” which is essentially territory of one country that can only be accessed via another country.

Yet Bald Eagle, the only course on the peninsula, isn’t some run-of-the-mill design. Built by Canadian architect Wayne Carleton, Bald Eagle is one of the best courses in the Pacific Northwest. From the tips, it’s an at-sea-level 6,868-yard test with plenty of ponds and wetlands that come into play. With isolated corridors that meander through towering cedar and fir — as well as beautiful shaping and bunkering — it’s everything you’d expect from a first-rate West Coast course. And it’s only 30 minutes from downtown Vancouver, all for regular rates between $32-$42. Well worth the drive. If only you wouldn’t get turned back at the border.

Needless to say, the situation at Bald Eagle, which is a year-round facility, is unique, a rather bleak anomaly in golfdom: a course, due to its strange geographic location, rendered unreachable, shut off from its clientele.

“Ninety-nine percent of our customers are from Canada,” says Kyle German, the general manager and head professional at the course, a dual citizen who is “stuck” on the Canadian side in the Greater Vancouver area. “So there really was no other option but to close the course. We’re hoping the situation changes soon but it looks like we are still weeks, if not months, away from re-opening. Until then, we’re just trying to keep the course somewhat ready for the day when we do open again. There’s not much else we can do. I haven’t been to work since they closed the border in March.”

Interestingly, this isn’t the first time the course has been closed for an extended period. The current ownership group, a small team from Canada, purchased the course in 2017. At that point, it had been shuttered for a year by the previous owners who basically ran out of money.

“When the current owners took over, the course was a disaster,” German says. “Only one green was salvageable. Everything else had to be refurbished and sodded. The bunkers were totally redone. Of course, this time around, the closure is for an entirely different reason. But we certainly know what the course looks like when it’s completely abandoned. And we don’t want to see that again.”

It is possible to leave the peninsula, if you have to, whether it be for medical reasons or other essential purposes. There’s now a weekly ferry that goes to Bellingham, Wash., which residents use for appointments or essentials.

“As far as what’s here, not much,” says Hoole, who lives near the course. “We have a grocery store. A couple of gas stations. One bar that closes early. And that’s about it.”

“Oh,” he adds with a smirk, “and we used to have a real golf course with flagsticks.”

However, the majority of the residents who call Point Roberts home — approximately 1,300 of them — actually want to stay put and hunker down for the long haul. They have not had one single case of Covid-19, a feat that has drawn international attention. In fact, Point Roberts has been dubbed the safest place in America. Naturally, the residents want to keep it that way.

Sadly, for Hoole, it means the golf course can be a rather lonely place these days.

“There are pros and cons to all of this,” he says. “To be completely honest, not having the constant pressure of maintaining a championship-caliber golf course at a tournament-ready standard is a relief. I don’t have to start my day at 4 in the morning. I start at 9. Ask any superintendent, that’s unheard of. And, of course, certain things, like the bunkers, flower beds, low-traffic areas, and so on, I basically don’t have to worry about. Correction, the entire course is currently a low-traffic area. But you know what I mean.”

The current closure agreement is set to expire on June 21. Until then, Hoole will keep mowing, maintaining and hoping.

“I really miss my crew,” he says. “I miss the interaction and the camaraderie. I miss the energy of having people here. And, of course, I miss seeing the flags flickering in the breeze.”

Andrew Penner is a freelance writer and photographer based in Calgary, Alberta. You can follow him on Instagram here: @andrewpennerphotography.