Money Game: Why a patron-less Masters is so financially significant for Augusta locals

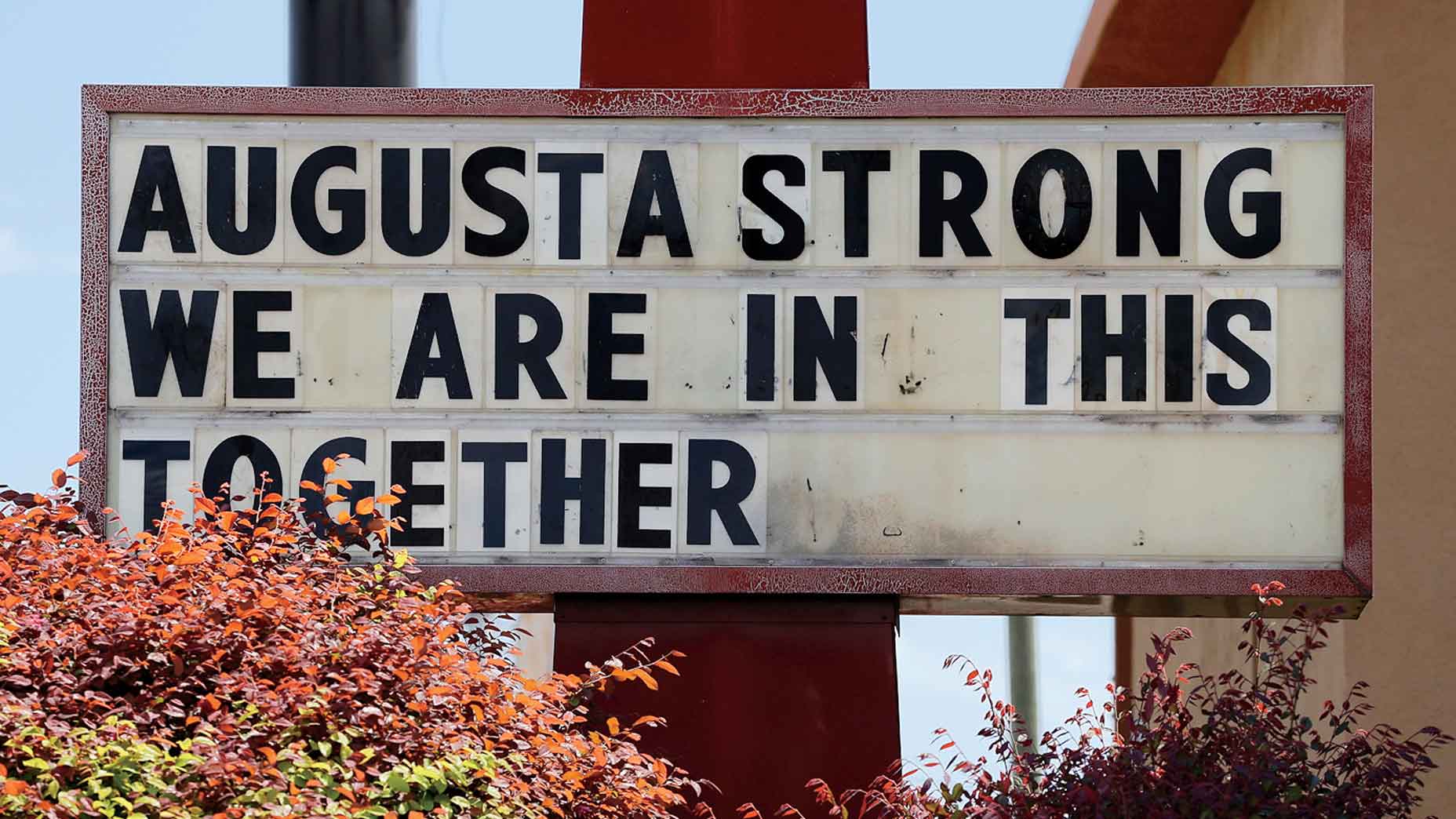

Covid-related closures in March 2020 inspired a message of solidarity from Augusta’s rarely empty TBonz Steakhouse.

Getty Images

The Reverend Doctor Joe Bowden hasn’t missed a week at the Masters in 56 years, from practice rounds on Monday to the trophy presentation on Sunday. And “Doc” — as the unofficial physician to the Masters staff and the starter for the “appreciation day” tournament that closes Augusta National in May is known — had no plans to miss number 57.

But this year, because of the coronavirus, he and his son Tripp, a one-time caddie at Augusta National who often accompanies him, and tens of thousands of other patrons will have to forgo the annual tradition of golf, pimento-cheese sandwiches and sublimely lubricated nights. What’s arguably more devastating is the financial setback the city of Augusta will experience.

“It’s hard to find an individual, group or business [in this town] that’s not impacted by the tournament,” Doc says.

In this pandemic year, the absence of galleries at PGA Tour stops hasn’t significantly altered our TV viewing experience, but it has taken a toll on host cities. It’s certain that even a destination as bustling as San Francisco took a hit with this year’s patron-less PGA Championship at Harding Park.

The Masters is a different economic engine altogether. It brings the world to Georgia’s second-largest city, one with a population of just 200,000, which ranks it well outside the top 100 cities in the U.S. In other words, a big-time tournament matters more to a place like Augusta — to the tune of an estimated $150 million in revenue for that one week alone. For business owners, the Masters delivers a once-a-year cash infusion that carries many of them through the following 11 and a half months.

Local golf courses — even private and resort ones as far away as Reynolds Plantation, some 80 miles west — bank lots of money by opening up their tee sheets to out-of-towners and charging up to $1,500 per foursome. Some clubs clear $500,000 or more during Masters week. Hotels, Ubers and taxis — the latter of which are permitted by the city to radically hike prices when Masters patrons come to town — are always packed. As are the bars and package stores. “Holy mackerel,” Doc says, “there’s a lot of alcohol consumed that week.”

Customarily, a restaurant like Calvert’s — opened in 1976, the same year Ray Floyd won his only green jacket — serves up more hand-cut steaks Masters week than at any other time of the year. In fact, business is five times that of an ordinary week. But Craig Calvert, who has owned the Augusta institution for 40 years, is dialing back expectations.

“This year, who knows?” he says. He just hopes Fuzzy Zoeller still visits, as he does every year. (Back in the day, Calvert’s was also Arnold Palmer’s post-Champions Dinner hangout.)

It’s not just Augusta’s chamber of commerce that’ll be rocked. Residents will feel it, too. Renting out their homes to Masters patrons or deep-pocketed corporate entities can mean enough cash to cover the cost of a new car or a dozen mortgage payments. No one would mistake the modest ranches and older homes on the other side of Washington Road, across from the main entrance to Augusta, for luxe manses. But by Masters standards they’re considered affordable at a rental fee of up to $50,000 per week. That pales in comparison to the $150,000 some homeowners get on the Hill, the posh western part of the city where Augusta State is located. Last year, that 150gs is what the cousin of a caddie friend pulled in for a seven-day use of his family’s estate.

“It’s common knowledge what people rent their homes for, but people don’t want to talk about it,” he says. “The town is small. It’s a hush-hush thing.”

The payday is nice, for sure, but so are the improvements corporate renters sometimes leave behind. Tripp Bowden, who wrote the memoir Freddie & Me, about Augusta’s legendary caddie master Freddie Bennett, and who has rented out his own home a half dozen times, recalls the story of friends who turned over their digs to ESPN. When they returned, they found new 56-inch flat-screen TVs mounted on the walls of every bedroom. Then there’s the good fortune of other friends who hosted executives from Electrolux and returned post-Masters week to new appliances throughout the house.

“It’s like it’s not even real,” Tripp says. “It’s like Fantasy Island.”

What the housing rentals bring in in total — at least for official state tax purposes — is hard to say. There are thousands of formal listings offered through the Masters Housing Bureau, which manages the rental process but takes a cut of the proceeds. And probably just as many gray market deals are made on the side.

One of the biggest takeaways from this oddball year will be a hard-won lesson in financial planning. Doc Bowden says he has more than a few friends who’ve already spent the rental deposit put down on their homes — typically half of the full fee.

“When you have the bird in the hand, you might say, ‘Mama, let’s buy us a new car,’” Doc chuckles. “Oops!”

One thing we can bank on: The 2020 Masters will take place. And we will all be watching.