When the Augusta National Women’s Amateur was announced in 2018, the larger sports world seemed split between two reactions: “That’s awesome!” and “Finally!” The tournament’s very staging was significant, not just because the title course was rolling out the green carpet but also because it had taken them so long to do so.

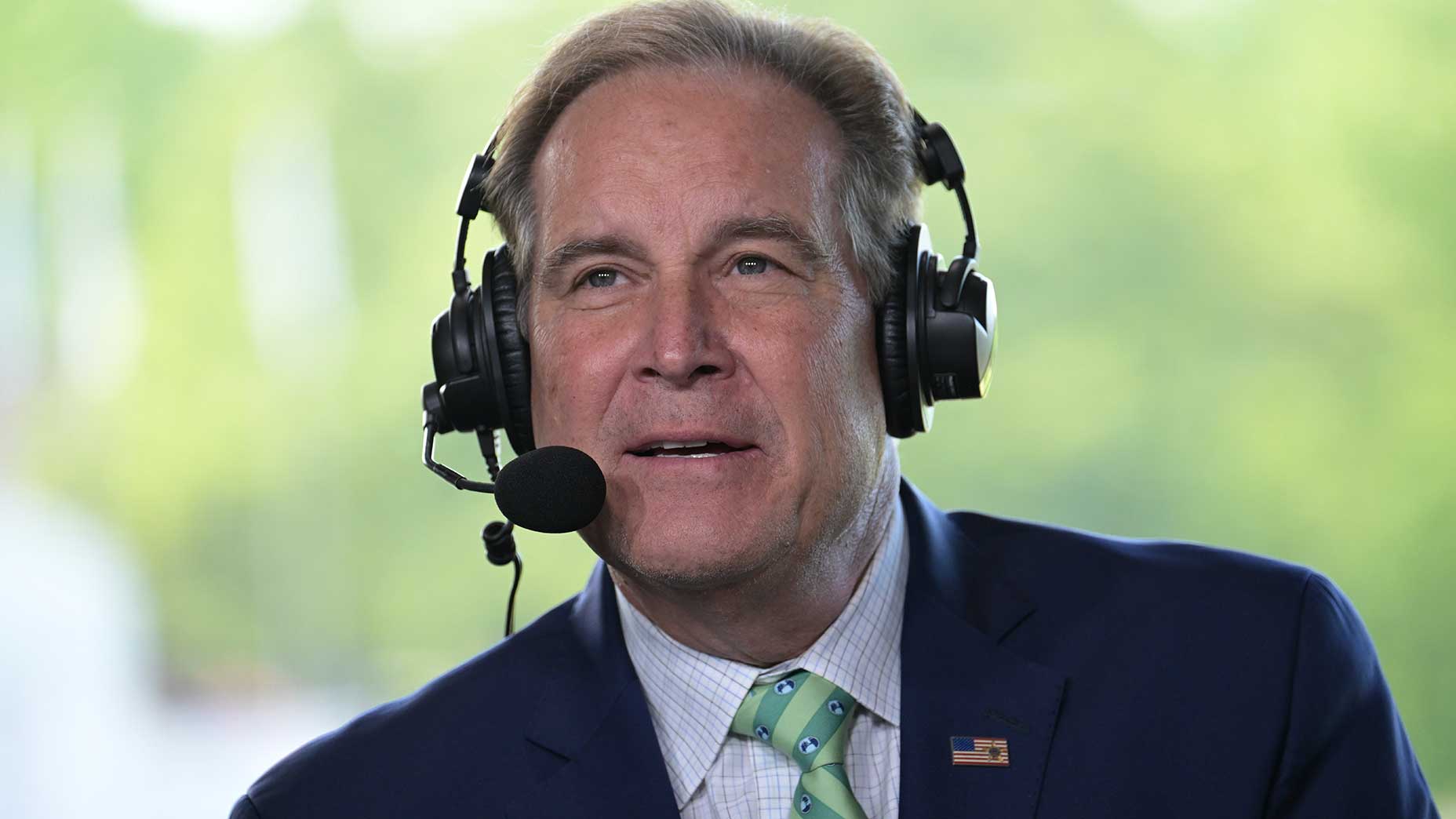

Against that backdrop, the ANWA has frequently been discussed in the context of Augusta National’s history and reputation; namely the times the club has been the battleground for fights over gender inequality. There was Martha Burk’s 2003 protest about the club’s lack of female members, Chairman Hootie Johnson’s rebuttal that a female member would not be admitted “at the point of a bayonet,” Augusta’s eventual admission of Condoleeza Rice and Darla Moore in 2012 and so on. A women’s tournament was a long time coming.

Perhaps, as it turns out, longer than the general public might think. The idea of women playing golf at Augusta National is hardly a 21st-century conception. Rather, it was part of the original plan.

THE ORIGINAL VISION

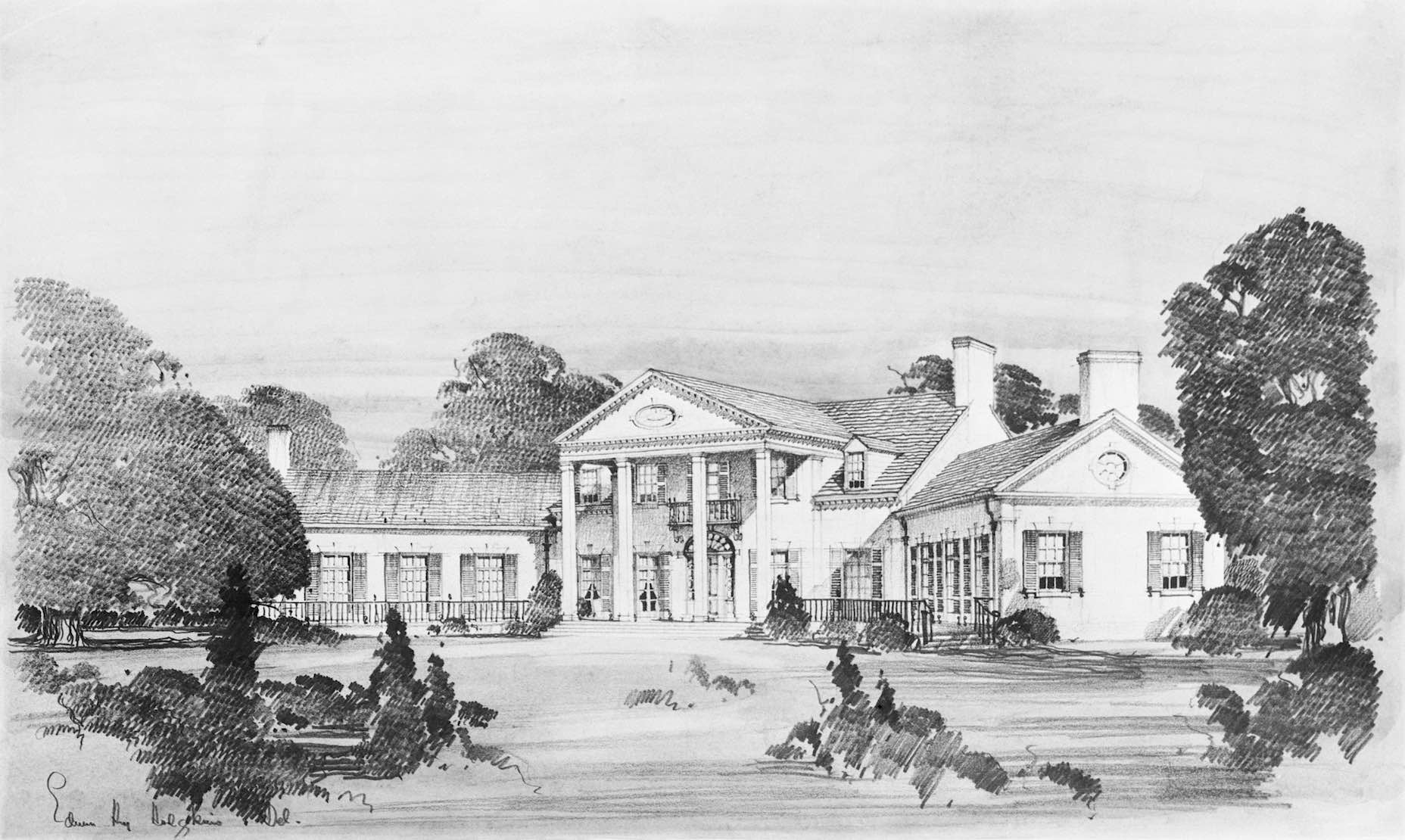

In 1931, when Grand Slam winner Bobby Jones and New York City stockbroker Clifford Roberts founded Augusta National, they envisioned a massive, national club. David Owen lays this out in his book on Augusta, The Making of the Masters: They planned to sign up 1,800 members, whose dues would help fund the MacKenzie-designed “championship course.”

Surely, Roberts figured, the attraction of the generation’s greatest golfer would be enough to entice interest from around the country. Jones, who spent most of his days as a lawyer in Atlanta, wanted a quiet place to play. According to Owen, the pair modeled their development after Marion Hollins’ work at Pasatiempo, down to hiring the same landscape architecture firm, the Olmsted Bros., to sketch out plans.

The vision was ambitious. Money from committed members would cover the course as well as tennis courts, squash courts, an 18-hole short course and a riding path. They’d revamp the clubhouse. They’d construct a hotel. Members would build houses around the perimeter.

Oh, and they’d design a ladies course, too.

THE LADIES’ COURSE

What does it mean to be a “ladies’ course?” More to the point, what did it mean in 1930?

As it turns out, by the time Alister MacKenzie was sketching out the routing for Augusta National, there was already a decades-old tradition of courses built for women. In Scotland, England and Ireland, ladies’ courses were built to complement their “championship” counterparts. These courses came in different shapes and sizes but they were generally short, clever and playable — though their specific characteristics varied widely, ranging from elaborate putting courses to 18-hole layouts that test players to this day.

The oldest ladies’ course was most likely developed at Scottish club North Berwick in 1867. (It still exists, now called the “Children’s Course.) Just south of St. Andrews, James Braid designed Lundin Ladies, a 2300-yard par-34 that featured Stonehenge-style stones on its second hole and retains its female-only membership to this day (men can play as guests). At Sunningdale Heath, Harry Colt built a 3700-yard par-60 that visitors can still play (at a bargain price, too!).

Other ladies’ courses followed, like those at Perth, Dunbar and Troon. Carnoustie added one too, something resembling a modern par-3 course. Formby Ladies Club, which boasts 350 members and features its own clubhouse, equipment and business plan, earned this description from Links Magazine just three years ago:

“The ladies’ course is encircled by the big course. It’s short but notoriously challenging: a man competing in a senior tournament once said, ‘You told me it was 5,300 yards long. You didn’t tell me it was one yard wide.’”

Around the same time at the opening at North Berwick, St. Andrews installed its giant putting green, “The Himalayas,” so that the wives of R&A members could pre-occupy themselves while their husbands played golf. Thus the The Ladies Putting Club of St. Andrews was born.

More than a century later, I’m hardly in a position to say whether these ladies’ courses were second-tier signs of female relegation or standalone sites of female empowerment. But the women who walked their fairways no doubt advanced the prospects of women in the game, in an era where influential golfers like Lord Moncrieff were saying things like this, per the Women’s Golf Journal:

“Not because we doubt a lady’s power to make a longer drive but because that cannot well be done without raising the club above the shoulder,” Moncrieff wrote. “Now we do not presume to dictate but we must observe that the posture and gestures requisite for a full swing are not particularly graceful when the player is clad in female dress.”

AUGUSTA’S LADIES’ COURSE

At Augusta National, the ladies’ course — like the championship course — would certainly have taken cues from its U.K. equivalents. But it’s also likely that this ladies’ course would have had American influence. That’s because it would have been overseen by Marion Hollins, who had won the Women’s Amateur, helped found Cypress Point Club and was the chief visionary for Women’s National Golf & Tennis Club in Glen Head, N.Y. The latter was a Long Island club (where men were welcome to play as guests, but only women could become members) developed as a female equivalent to The Creek Club down the road. Under Hollins’ watchful eye, a ladies’ club would hardly have been an afterthought.

Nor would the course have been the first of its kind on U.S. soil. Up the coast, Shinnecock Hills had been the first U.S. golf club to admit women as members (it did so from the outset). And in 1893, Shinny opened a ladies course of its own. In 1895, one of its female members won the Women’s Amateur. In 1900, the club hosted the Women’s Am. There was certainly precedent for prioritizing female involvement in the game.

Where would Augusta’s ladies course have fallen on this spectrum? It’s hard to say. Owen wrote this for the New Yorker: “As soon as their new club’s membership had passed a thousand, Jones and Roberts decided, they would build a second course, which, like Hollins’s Women’s National, would be geared specifically to women.” That implies a commitment to the second course as a respected standalone entity.

But because the club never threatened 1,000 members in its recruitment, we never got to see it. And while MacKenzie did release plans for an 18-hole, 2460-yard short course (with holes ranging from 60 to 190 yards) plans for the separate ladies’ course were never finalized. They were certainly never completed.

THE REALITY

Jones and Roberts picked a tough time to launch a golf course with a national membership. Rather than the 1,800 members they’d been planning to enroll, the pair signed up just 76 — in four years. According to Owens, the $350 initiation fee and $60 annual dues were too big an ask, despite tens of thousands of solicitations.

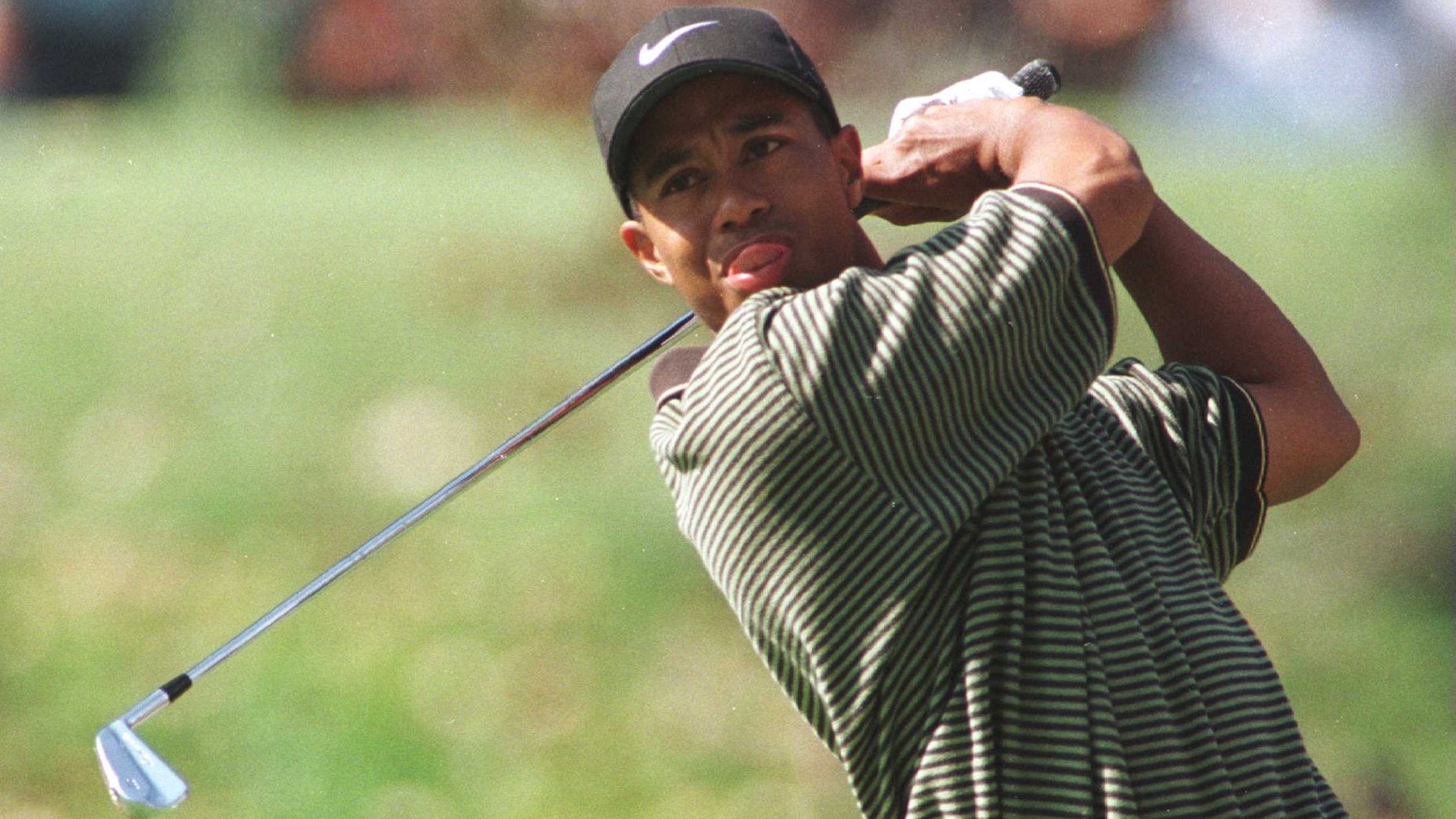

Augusta had hoped to attract the 1934 U.S. Open; that soon proved unlikely. Instead, Jones came out of retirement to lure a strong field to join him as player-host at the Augusta National Invitational, the tournament that would eventually become the Masters. Seventy-two players accepted their invitation the first year. Sixty-five showed for the second playing. Then 52, 46 and 42 the following three years. It was hardly an overnight success.

In other words, the original vision and the eventual success of the Masters could not have had less in common. MacKenzie died three months before Augusta’s first Invitational; he never received full payment for his work on the course nor did he live to see Augusta in its final form. Instead of the $100,000 clubhouse makeover, the club made do with the existing house, already the better part of a century old.

Needless to say, zero additional holes were built. Not MacKenzie’s 18-hole pitch ’n’ putt. Not Jones’ dream of a 90-yard 19th hole (between No. 18 green and the clubhouse). And not the ladies course.

It wasn’t until after World War II that Augusta National solidified its finances. In 1958, the course opened its nine-hole par-3 course. It was built on some of the same foundational principles as original Scottish ladies’ courses, but it was built with the all-male membership in mind. Women could play at Augusta National as guests, after all, but you’d be hard-pressed to say that any part of the club truly belonged to them.

THE REVERSAL

Augusta National was originally conceived as essentially a high-end Georgia residential community. These days, there’s not a person alive who could build a house on property.

But that’s hardly the only bit of the golf world that’s been flipped on its head as time has passed. Among the most interesting changes is in architectural preference: The types of courses once considered “ladies courses” are in vogue now more than ever. The biggest golf resorts in the world each have alternatives to full-length championship golf. Pinehurst has the Cradle. Pebble Beach just redid Peter Hay. Bandon Dunes has the 13-hole Preserve. Cabot Links has the Nest. Sand Valley has the Sandbox.

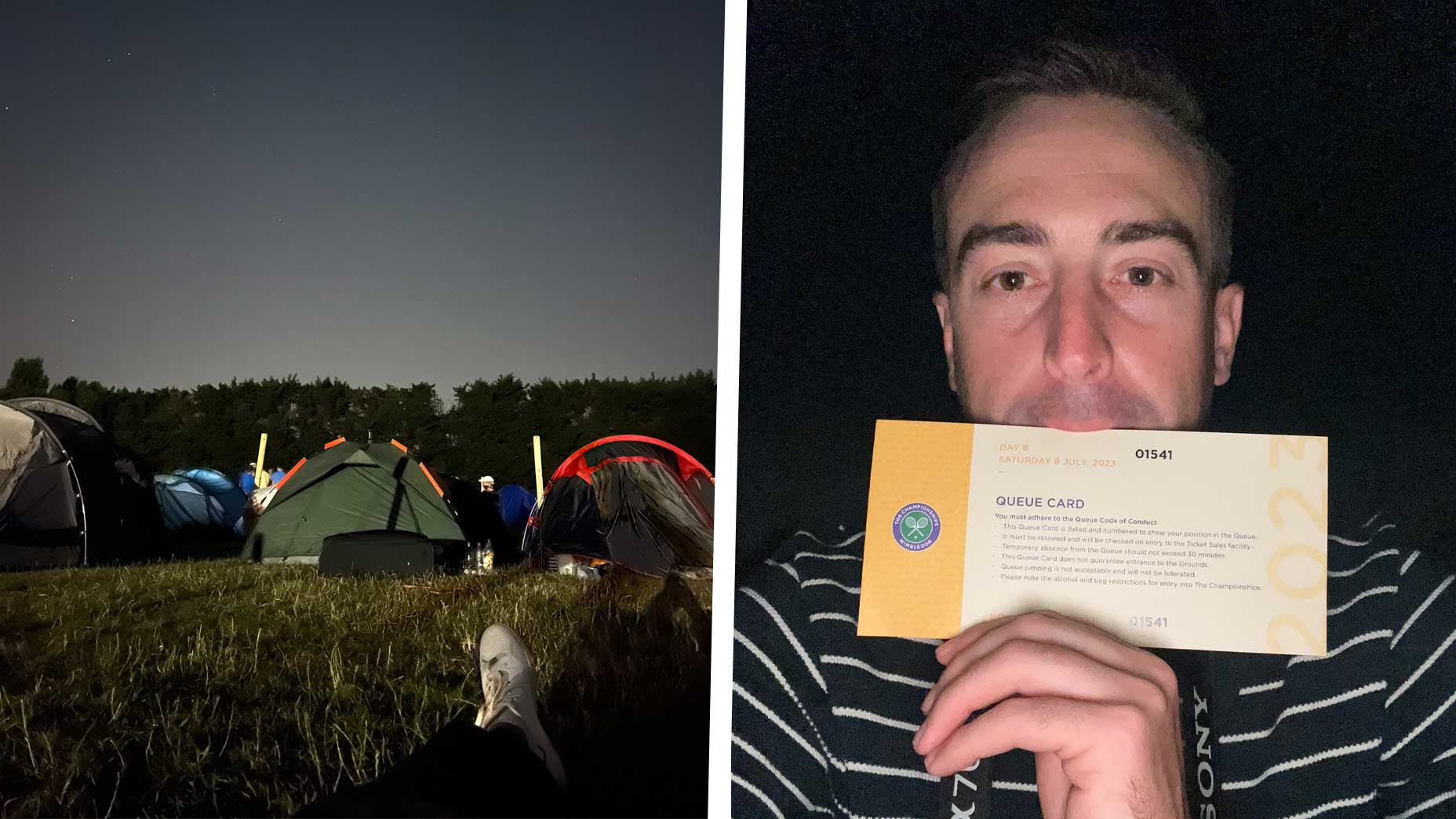

Putting courses are all the rage, too, modeled after the Himalayas at St. Andrews. Think Thistle Dhu at Pinehurst, The Punchbowl at Bandon, Drumlin at Erin Hills, Cascade at Gamble Sands or Driftwood at Sea Island. The Ladies Putting Club has become the envy of the modern golfing world. Golf need not be pure brawn.

It’s some small sign of progress, then, that these courses are built and marketed without gender in mind. Indeed, they’re trumpeted as essential features of any golf getaway, on this site and others. This weekend, countless buddies on countless trips will make their way around fun-sized courses.

Meanwhile, the rest of us will be at home, watching the best female amateurs take on Augusta National’s championship course, jealous of their skill — and of their access to the most famous course in all of golf.