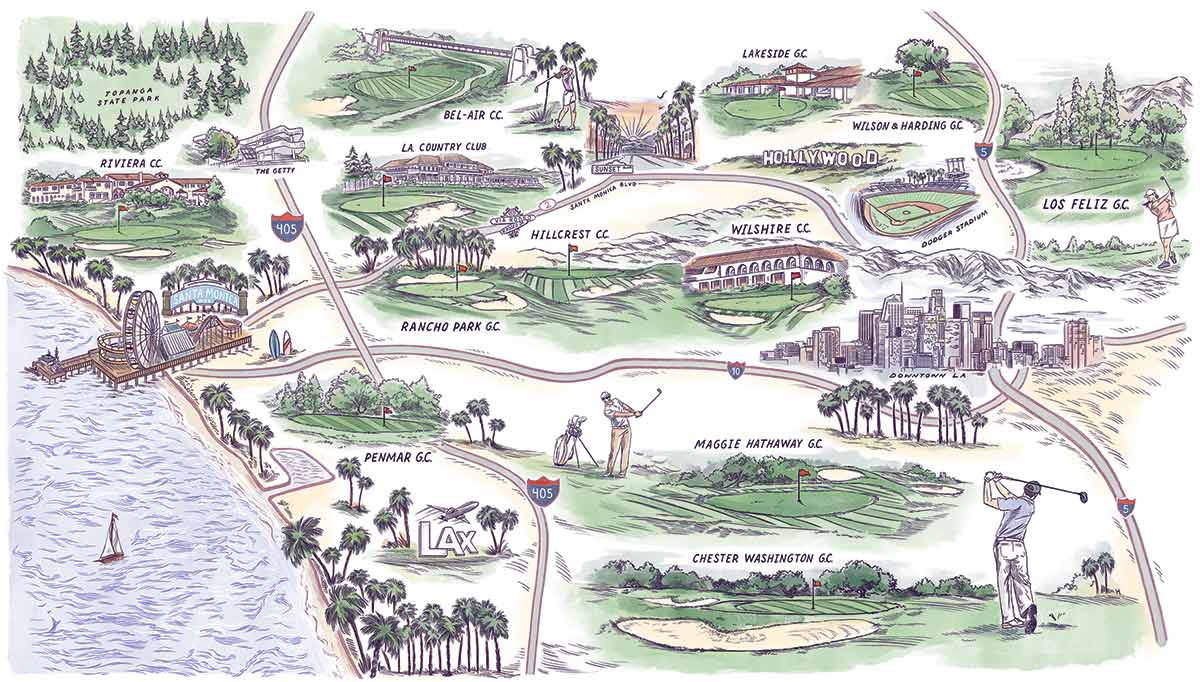

Lights, camera, action! Why U.S. Open-host Los Angeles just may be the golfiest place in America

Los Angeles Country Club, host of the 2023 U.S. Open.

CHANNING BENJAMIN

Like so much in this city, it can bedazzle, the sparkle of its courses matched by the star power of those who play them.

L.A. golf is Riviera, gilded Golden Age design, Tiger-hosted Tour stop, home course to Larry David and Adam Sandler. It is Jason Bateman and Chris O’Donnell clinking post-round cocktails with Dennis Quaid on the sun-splashed veranda of Bel-Air Country Club.

L.A. golf is Justin Timberlake, Jack Nicholson, Joe Pesci. It is Brentwood and Hillcrest, Lakeside and Sherwood. It is Will Ferrell hosting a hit-and-giggle at Wilshire Country Club, and also Mark Wahlberg, Ferrell’s fellow Wilshire member, sprinting through 18 in less time than it takes to screen one of his films.

You get the picture: blockbuster stuff. But like any big production, it is more than the names on its marquee. In its diversity and scale, the L.A. golf scene is unmatched in the country, populated by a rich assortment of public tracks and practice grounds, many as pedigreed as they are unpretentious and crowded with an only-in-L.A. ensemble cast. You come across them as you scroll down through the credits, pausing to appreciate the characters and courses in a spectacle as sprawling as the city itself.

“What can I f—ing say? I’m not a country club guy!”

That cigarette-thickened voice belongs to Ron del Barrio, an affable, foulmouthed, semi-cultish figure who, at 57, has a well-earned reputation as golf guru to the stars and pretty much anyone who comes within his reach. On this breezy April afternoon, he is lounging in the café at Weddington Golf & Tennis, a green stitch in the sprawl of Studio City, a quick skip from the Jaws shark tours at Universal Studios and two blocks from the house where he was raised. As a boy growing up in the 1970s, del Barrio loved most sports but thought that golf was stupid.

“It was Bing Crosby white guys — tweedy, stuffy,” he says. “Same people who played squash with Biff and Ted.”

He looked at it that way until his late teens, when he joined the fire department and discovered that his older colleagues liked the game. Wanting to be like them, he picked up golf himself. A few turns of the calendar and a bunch of lessons later, del Barrio was ready to start teaching others. At Weddington, a public access facility with a short course and a range that was nowhere near as nose-up as its name suggested, he found the perfect spot to hang a shingle. Its fake-turf hitting areas were come one, come all. Bob Hope and Dean Martin ranked among the regulars. Ditto studio execs and business tycoons. But blue-collar types also abounded, and del Barrio felt so welcome that he didn’t bother trying to hide his tattoos.

One evening, Smokey Robinson showed up to bang a bucket. Keen to win him as a student, del Barrio snagged a stall behind the Motown legend and pulled a sly one.

“I had these cap gun caps you could lick and stick onto anything,” del Barrio says. “So, I stick them on a few golf balls and start hitting. Bam, bam, bam! Smokey was blown away by my power.”

Instead of asking for a lesson, though, Robinson offered to sponsor del Barrio on the Palm Springs mini tours. That deal lasted for a few years, and Robinson was willing to keep it up for longer. But, knowing that the living was destined to be lean, del Barrio cut bait and returned to Weddington. That was in the early ’80s. He’s been there ever since, building a client base that ranges from Will Smith, Sly Stallone and Kevin Costner to the plumber’s apprentice down the street.

From his fixed position on the far end of the range, del Barrio has watched the L.A. golf scene morph around him — the Tiger youth movement giving way to the viral trends of the Instagram age. The loosening of dress codes. The relaxation of calcified customs, urged on further by waves of Covid converts. Those currents are awash in the game throughout the country. But nowhere are they stronger than in a city famously obsessed with staying young. Del Barrio detects it nearly every place he turns. The fashion influences from skate and surf and punk. The cultural shift toward casual-cool.

“I’m so glad I’ve been around long enough to see this new narrative in golf,” del Barrio says. He gestures around him. A twenty-something golfer is walking by in board shorts. Outside, on the practice green, the actor Judd Hirsh is stroking putts.

“And I think the older guys around here are into the new narrative too,” del Barrio continues. “They’re dressing younger. They’re trying to be with it. Even the old country club stiffs are happy about the changes. A lot of them have come up to me and said, ‘You know, I never wanted to be that uptight guy in the first place. It just felt like I had to act that way.’”

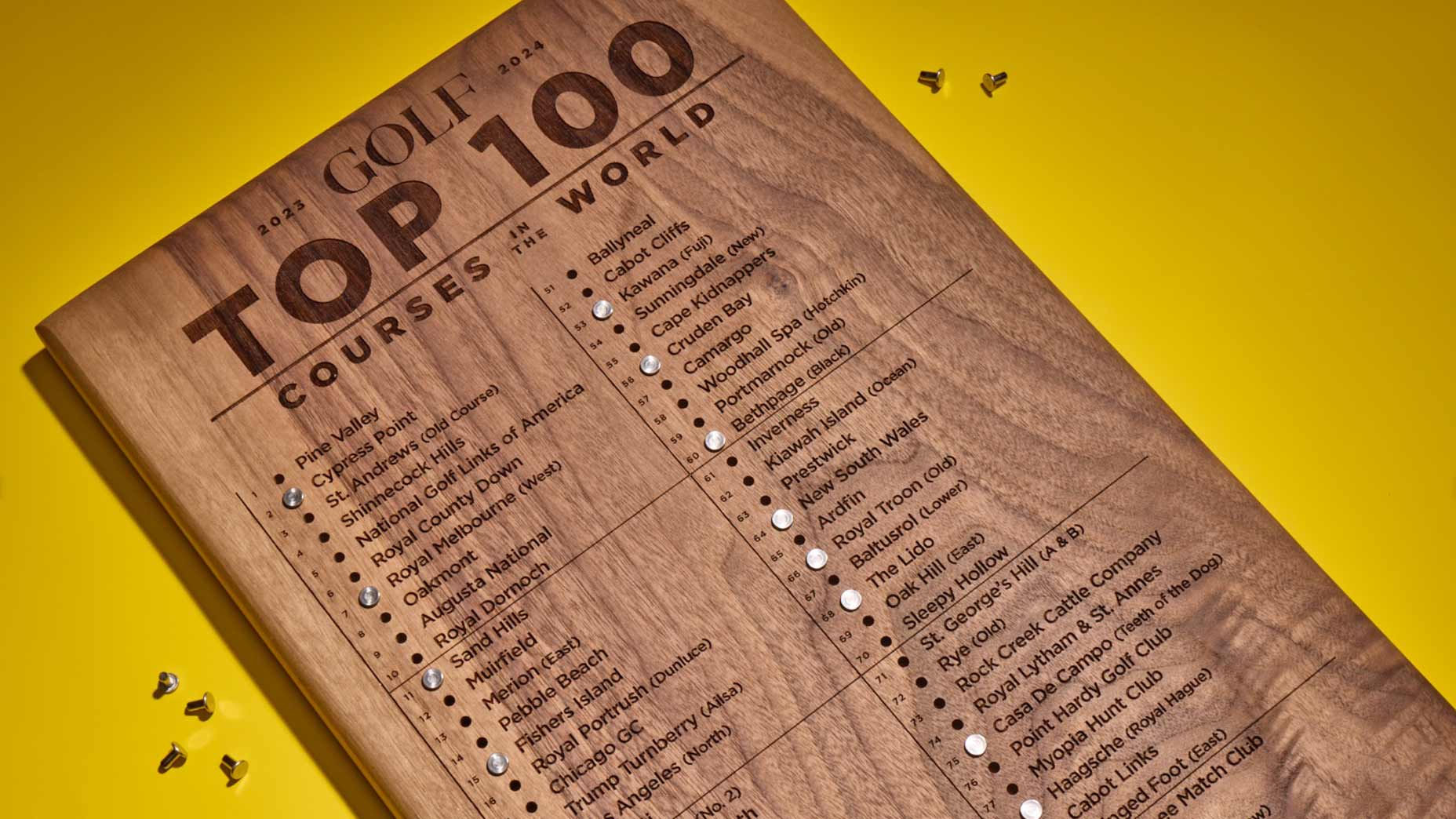

There are lots of local places where a golfer with those leanings can feel at ease. Los Angeles County is home to 20 municipal courses, the largest and busiest network of its kind in the country. Because the freeway system is large and busy, too, getting to those tracks requires commitment. But a cluster of the finest lie within city limits, including the Harding and Wilson courses at Griffith Park, 36 holes laid out in the 1920s by George C. Thomas, architect of Riviera, Bel-Air and Los Angeles Country Club, where this month’s national championship will be held.

Two miles south of LACC, another muni grandee — William P. Bell-designed Rancho Park — has a rich tournament past, its history highlighted by multiple Champions and LPGA Tour events, as well as 18 iterations of the Los Angeles Open. A reminder of the rolling, tree-lined test Rancho has posed stands by the 18th tee, where a plaque tells of the time, in 1963, that Arnold Palmer took 12 strokes to play the hole. An accompanying map shows where every one of those dozen shots went.

Like most public courses around L.A., Rancho Park is packed, its tees and fairways stacked from dawn to dusk with a cross-generational rainbow coalition that reflects the city’s diverse demographics. Inclusivity is a defining feature of L.A.’s muni scene.

Angelique Johnson feels indebted to the people who helped make that so.

Tall, athletic and effervescent, with silver-streaked black hair spilling past her shoulders, Johnson didn’t play golf as a girl growing up in southwest L.A. in the 1960s. But her grandmother did, in a regular group led by Maggie Hathaway, a blues singer, writer and civil-rights activist who spent decades agitating against discrimination on public courses, organizing pickets and sit-ins on their grounds. Johnson has childhood memories of sitting in the local beauty shop with her grandma, Hathaway and their gaggle of golfers, eavesdropping on conversations that spanned from social justice to Saturday skins.

“Even though I wasn’t a golfer then, golf was everywhere around me,” says Johnson. “I feel like it was part of my destiny.”

In a twist a screenwriter might have scripted, Johnson didn’t start playing until her twenties, while working in human resources, but she got good quickly, quit her nine-to-five and plunged into the golf business, serving first as a starter and then rising through the ranks to become the head professional at Chester Washington Golf Course, one of the first L.A. County courses that Hathaway helped integrate.

The course sits on Charlie Sifford Drive, an address that hints at its history as a hub for Black golfers in the ’50s and ’60s. Sifford himself was a fixture at the muni, hustling in money games with the celebrity-athlete likes of Jim Brown, Joe Louis and Sugar Ray Robinson. Photos from that era hang in the Chester Washington clubhouse, and Johnson makes a point of pausing to admire them when she passes through.

Though she left her head pro post in 2018, she remains a familiar face at the course, dropping by to greet friends or give playing lessons to golfers of all ages and backgrounds.

“The more the merrier — that’s what Maggie would have wanted,” says Johnson, who remained close with Hathaway until her death in 2001. “What I want to do is keep her legacy alive.”

An old joke about L.A. is that everyone’s an actor or a waiter auditioning to be an actor. Nowadays, it seems that everyone’s a golfer or trying to learn the game. Writers. Singers. Key-grip operators — the creative fabric of an entertainment capital threaded through the crowds at your local course. Make the rounds of the city and you’ll meet unconventional golf-obsessives like Taylor Moore, 42, a real-estate attorney and part-time stand-up comic who moonlights as an instructor at Tregnan Golf Academy, a tiny, city-run facility devoted primarily to kids. You’ll bump into laid-back golf buddies like Jordan De Guzman and Mike Isberto, former rock bandmates from the Inland Empire, east of L.A., who find respite from their office jobs with morning outings at Los Feliz Golf Course, a shabby-chic par 3 in the hip neighborhood of the same name.

“Just trying to get more green time and less screen time,” De Guzman says.

The biggest obstacle to that isn’t navigating traffic. It’s landing a tee time. Never easy to penetrate in years past, city reservation systems have more recently been bombarded by bots — automated callers that compete for bookings in an already frenzied market.

As many locals tell it, dialing in as a human is as hopeless as rush hour on the 405. Compounding the headache is that the number of daily-fee courses in L.A. has dwindled, hollowing out the middle of the market, leaving little but the private clubs and the congested munis. No wonder many look to other outlets for their fix. Some hit up the new Topgolf near LAX. Others shell out for buckets at Aroma Golf, a multi-decker driving range in Koreatown that doubles as a day spa. Still others go so far as to establish their own golf clubs, unhindered by the fact that they don’t have a course.

That was the case with Garrett Leight.

As the creator of an eponymous sunglass-design company, with retail stores in La Brea, Brooklyn and beyond, Leight does not lack for course access; he is a member of Sherwood Country Club, north of the city, where a long list of A-listers, including Wayne Gretzky, belong.

“But,” he says, “I’m also a serial entrepreneur, and I’m into anything that gets my creative juices flowing.”

Inspiration struck in 2019 when he organized a Skins game with some 20-odd friends and, unable to help himself, designed hats and T-shirts for everyone in it. One thing led to another and Penmar Social Club was born. Leight didn’t call it that at first. The original name was Venice Country Club. But “country club” ran counter to the spirit.

“It was really the community, the social element that mattered,” Leight says. “It was a social club.”

Penmar, meanwhile, was the course they had played, a charming nine-hole Venice muni known outside L.A. as the grassy patch where Harrison Ford crash-landed a World War II-era plane in 2015.

In its conception, Penmar Social Club seemed at once national and local, animated by the industry-wide golf-as-lifestyle zeitgeist but also energized by the grungy-artist affluence of its surrounds. Anyway, people dug it. Leight held more events, and the club’s ranks swelled to a point where two of Leight’s friends — Jeff Hastings and Todd Moffett — came aboard to help him steer the ship.

“We’re still pretty much flying by the seat of our pants,” Leight says. “Which is how I like it.”

They are organized enough to hold regular events, including four “majors,” a three-club “Players Championship” and a season-long FedEx Cup-style points chase. Of the club’s 185 members, upwards of 100 tend to show up for the competitions, which are held on a rota of public courses and vary in intensity from one competition to the next.

“Some people are addicted to the physics of golf and good shotmaking. Some are just in it for the drinking,” Leight says.

Four years into its life, the closest Penmar Social Club can come to claiming a home course is humble, nine-hole Penmar Golf Course. But the group does now have a physical footprint. Early this spring, Leight and Co. cut the ribbon on a brick-and-mortar clubhouse, in a renovated space on a busy street in Venice, squeezed between a dentist’s office and an architecture firm. Its curated interior is perfectly on-brand: comfy couches, patterned carpet, jazzy vinyl collection and a turntable for it: a speakeasy without the liquor sales. Given space limitations, membership to this part of the club has been capped at 40. Already, there is a waiting list.

“Deep down, we are dive-bar people, but we’ve tasted some good stuff,” Leight says. “The idea is to have a cool but casual place that gives you the feeling of a club membership, but you don’t have to be wealthy to belong.”

It’s late afternoon, and Leight is standing near the back of the space, leaning one elbow on the small clubhouse bar. Bebop is playing. Two members are lounging on a couch in one corner. Another is waggling a golf club.

“Golf is a thread that connects us,” Leight says. “But, really, there are lots of other things we can do collectively. I want to start a bowling league, maybe a poker league.”

Near the clubhouse entrance is a golf simulator, which members use for everything from serious practice to informal closest-to-the-hole competitions.

Leight picks up a 7-iron. Projected on the screen is an image of a seaside par 3 in Cabo. Leight waggles, swings. His simulated shot caroms off a rock onto a beach. He smiles and shrugs, a genuine reaction to a virtual expression of a real-world experience.

That, too, seems very much L.A.