The course now has a great resemblance to real links land,” the architect Alister Mackenzie wrote in the early 1930s, of his new design in Northern California.

The layout, he added, “will be as sporty as the Old Course at St. Andrews and as picturesque a golf course as any in the world.”

He wasn’t referring to his work at Cypress Point.

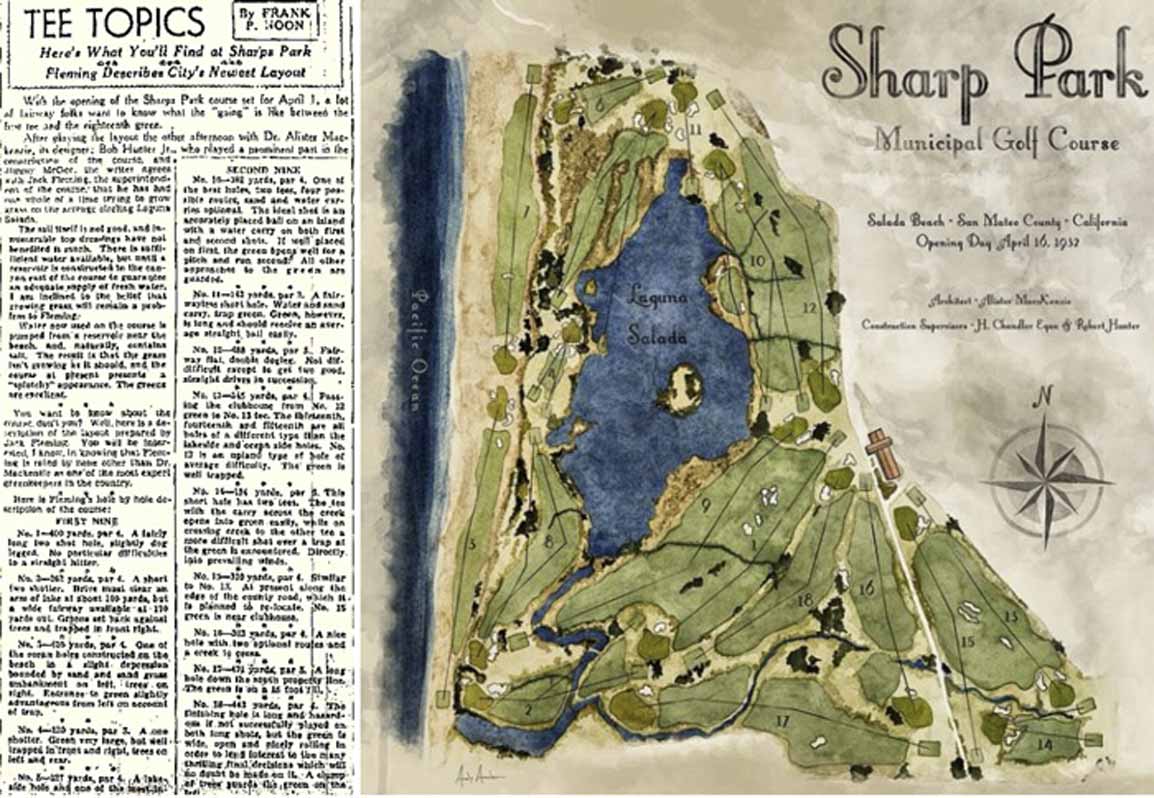

The project was Sharp Park, and while it couldn’t equal Cypress in prestige, it laid claim to a pretty cool location, on a sandy site just south of San Francisco, its western edges kissing up against the Pacific.

What’s more, it was a muni, which placed it all the nearer to Mackenzie’s heart.

Though you might not know it from his most famous courses (last we checked, Cypress, Augusta National and Royal Melbourne still weren’t offering tee times on GolfNow), Mackenzie was a big-time muni booster, a believer in government-backed golf for the masses.

His favorite muni was the greatest of them all, the Old Course in St. Andrews, which he saw as a blueprint for the game around the globe.

“I hope to live to see the day when there are the crowds of municipal courses, as in Scotland, cropping up all over the world,” the physician-turned-architect wrote in his posthumously published book, The Spirit of St. Andrews. “It would help enormously in increasing the health, the virility and the prosperity of nations, and would do much to counteract discontent.”

In another time, Mackenzie might have stamped his name on more munis. But in the late 1920s, when he crossed the pond and started getting busy in California, not a lot of city courses were being built (the Golden Age of munis in this country didn’t really kick off until 1935, with the launch of the federally funded Works Progress Administration, and Mackenzie died in 1934), so Mackenzie did like the bank robber Willie Sutton and went where the opportunity was.

Sharp Park was a rarity, a swatch of splendid city-owned land on which to work his magic. Taking full advantage of the site, Mackenzie drew up an aggressive routing, with five holes threaded so close to the Pacific you could taste the salt spray.

Those holes were very nice, but they didn’t last. By the 1940s, the ocean had claimed them, and a seawall was constructed to prevent the waves from claiming more.

No one denies that Sharp Park today is different from the course that Mackenzie first designed. A jerry-rigged routing now takes players east across Highway 1 to four holes in the hills, partial compensation for the holes lost along the water. Another original hole was split into two to bring the total number back to 18.

But plenty of Mackenzie’s imprint remains. In the clever mounding and deceptive bunkering. In the artful curl of doglegs, bent around wind-sculpted Cypress trees.

Then there’s this: Sharp Park is world’s only Mackenzie-designed muni located on the coast (we’ll grant him a sliver of credit for the Eden Course in St. Andrews, where Mackenzie worked as an assistant to the architect of record, H.S. Colt).

Aside from ocean surges, Sharp Park has dealt with a myriad of existential threats throughout the decades. Like many munis, it has weathered droughts and economic downturns. In recent years, it endured a drawn out legal battle against environmentalists who sought to have it shuttered to protect endangered frogs and snakes. That fight finally ended when a federal judge ruled that all three populations―amphibians, reptiles and golfers―could coexist.

But now there is the matter of … do we really have to say?

This month was meant to mark the eighth annual playing of the Mackenzie Tournament, a come-one, come-all five-person scramble competition that doubles as a fundraiser for the course, with a post-round barbecue and golf auction. Since its inauguration, in 2012, the tournament has raised some $300,000 to help keep Sharp Park breathing, covering everything from legal fees to course improvements. A key source of financial support, it’s been scrapped for now, with a tentative rescheduling for August, or early September, to coincide with what would be Mackenzie’s 150th birthday.

Nothing is guaranteed.

Uncertainty is a word in frequent use these days, but uncertainty is pretty much Sharp Park’s permanent state.

In the coming weeks, as golf courses reopen across California, Sharp Park will reopen, too, in a climate as challenging as any it has faced. Forecasters say another drought is looming, to say nothing of budget cuts, which are bound to leave muni coffers dry.

Hard choices undoubtedly await.

To understand what a society values, you can look not only to the new things it produces but also to the old things it preserves.

Mackenzie made it clear what he thought worth keeping.

“Health and happiness are everything in this world,” he wrote. And golf, he argued, promoted both.

Time will tell how many of us feel the same.

This is part of our Muni Monday series, spotlighting stories from the world of city- and county-owned golf courses around the world. Got a muni story that needs telling? Send tips to Dylan Dethier or to munimondays@gmail.com and follow Muni Mondays on Instagram.