Property brothers: Mike and Chris Keiser inherited their father’s ambition, then got the bug to build

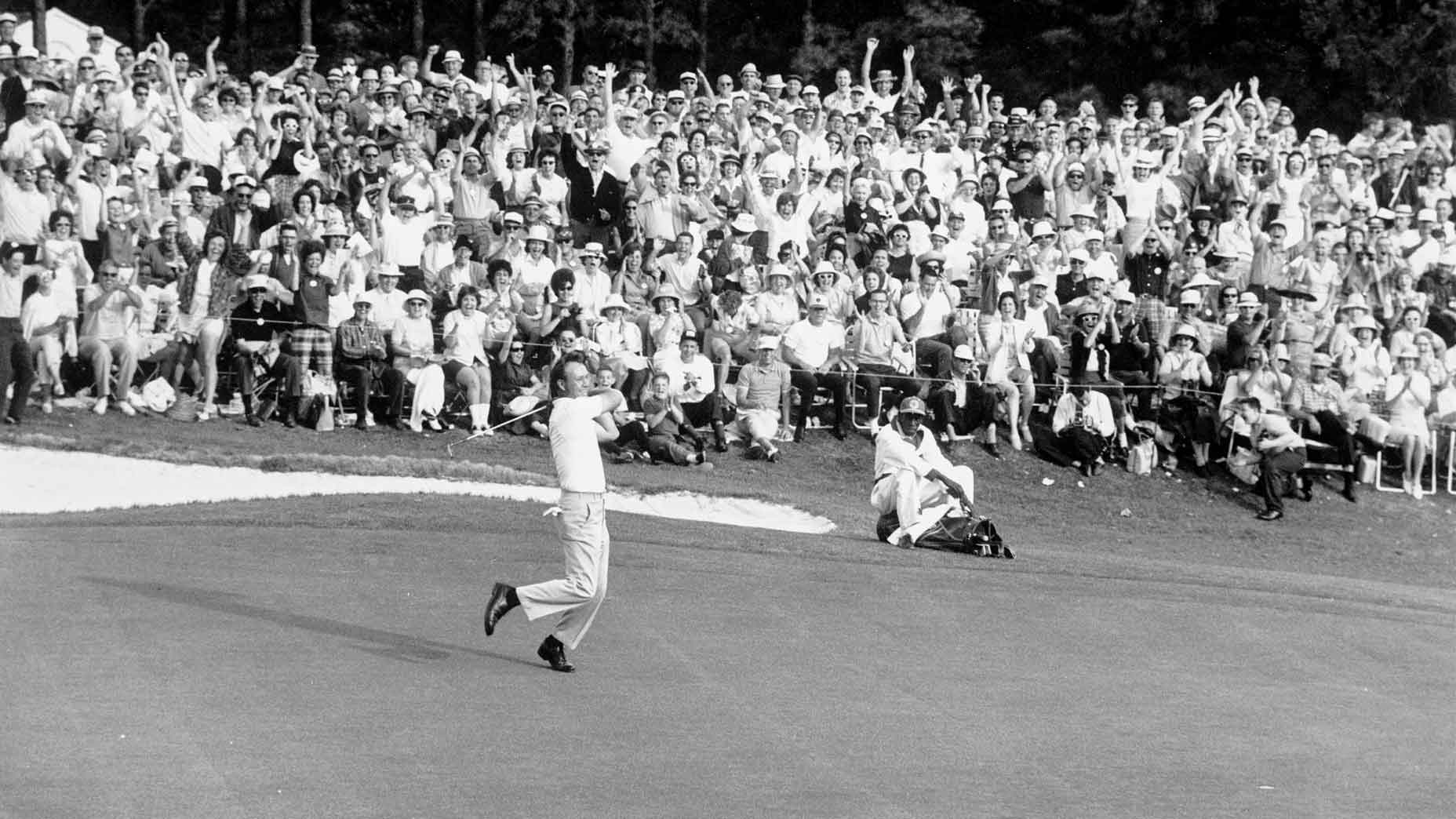

The Keiser boys — Chris (left) and Michael — atop the heaving greenery at Madison’s Glen Golf Park.

Christoper Lane

It’s a sunny afternoon at Glen Golf Park, a nine-hole muni in Madison, Wis., that he helped remake, and Michael Keiser is standing on the practice green, trying to get a handle on his stroke.

“I’ve been fighting the yips,” he says, as his bid at a slippery four-footer slides past the hole. Barely has the ball gone begging when his younger brother, Chris, steps up and pours one in.

“Mark it down in the record books,” Michael says. “You win again!”

Chris shrugs and offers an apologetic smile. At 41 and 34, the Keiser brothers are a far cry from fiery sibling rivals. By their own account, they’ve been best friends since boyhood. In more recent years, they’ve also become colleagues — business partners in one of the golf industry’s most dynamic pairings.

If you recognize their family name, that’s not surprising. Their father is Mike Keiser, the pioneering founder of Bandon Dunes. Like their dad, Michael and Chris are course developers, spearheading projects that, like Bandon, have emerged as must experiences for anyone who loves the game. The brothers’ lineage is central to their story. It helps explain how they have come so far, so fast. But it’s not the only source of their success.

“We’re proud of our father. We’re his biggest fans. We’re inspired by him and we’ve benefited greatly from everything he’s done,” Michael says. “At the same time — I don’t really know how else to put it — we’ve been kinda doing our own thing.”

Ground zero for them is Sand Valley, the Wisconsin destination roughly two hours north of Madison that draws on the Bandon model by infusing great golf with a distinctive sense of place. As Michael and Chris readily concede, the resort would not exist without their father. Mike bought the land and offered early guidance. But it now operates entirely without him. His sons have propelled it to where it is today, with three courses completed, two other headliners set to open and room for several more amid a nearly 10,000-acre swath of natural sand barrens that the Keisers are helping to restore.

Beyond their sizable ambitions at Sand Valley, Michael and Chris are pursuing three other projects in three different states, each large enough for at least four courses. Opportunities abound. Someone is always pitching them on something, oftentimes with tantalizing prospects.

Still, Chris says, “We’re always looking for reasons to say no.” Their dad, at 77, remains a sounding board, but the buck now stops with them.

“I’ve been telling people for years that the story going forward was going to be about the boys,” says the architect David McLay Kidd, who designed the first course at Bandon Dunes and the second course, Mammoth Dunes, at Sand Valley. “You could see it at Sand Valley. That was where the torch got passed.”

Not that the transition was preordained. Growing up, the Keiser kids were free to follow their owns paths. Michael, being older, came to the game first, playing what amounted to wilderness golf on rumpled family land beside Lake Michigan that his dad later turned into his first course, the Dunes Club. As part of their father-son outings, Mike would whack balls into the water and Michael would snorkel out to retrieve them.

Chris has early memories of the Dunes Club, too, and of family excursions (Michael and Chris also have two sisters, who are not involved in golf) to the Oregon coast that were pitched as camping trips and felt like them, except that Mike was also scouting sites in Bandon. That was his way: to expose his kids to golf without imposing it on them. Even pilgrimages to Scotland when the boys were older were treated as adventures — not required education on the glories of the links.

“My dad was pretty subtle about the way he drew us in,” Michael says.

During summer breaks from college, Michael worked at Bandon, first on the maintenance crew and later as a caddie, keeping up while shutting up about his background.

“I didn’t want to be looked at as the owner’s son,” he says. “I was at the age. I wanted to be my own man.”

After graduation, he lit out for Tasmania and spent a year in operations at Barnbougle Dunes, the Down Under gem his father helped finance. Chris, for his part, taught school in Chicago for two years after college before launching an e-commerce business that dovetailed with digital initiatives at Bandon. In retrospect, it’s clear that family interests were converging. But not until Sand Valley did the stars fully align.

The resort, which opened in 2017, has been described as an inland Bandon — and that is true to a point. In keeping with the Keiser playbook, golf, as Michael puts it, “comes first, second and third.” But what follows is an array of activities — including grass-court tennis, bocce, fat-tire biking and fishing — that cast a wider, family-friendly net. Sand Valley builds on a foundation but also breaks from it.

“The goal was never to simply replicate the success of Bandon Dunes,” Chris says. “That’s the challenge that I think is getting harder and harder. How do you build something great that differentiates itself from what has come before?”

That means not just living a life of leisure but living a life of purpose.

For the Keisers, two Wisconsin courses-in-the-making fit that bill: Sedge Valley and the Lido. The former is a Tom Doak design, inspired in part by the great heathland courses outside London, that will be the third 18-holer at Sand Valley when it opens in 2024. The latter is also a Doak commission but not his design. It’s a clone of the Lido, C.B. Macdonald’s long-lost Long Island masterpiece, with every contour of the fabled original restored to within a fraction of an inch.

Already open for preview play, the Lido sits across the road from Sand Valley and will operate as a private club with a tranche of public times available through the resort — a hybrid model borrowed from the UK, where, with rare exceptions, even the most exclusive courses still offer a way in.

It’s not lost on the Keisers that getting access to great golf is often more a matter of luck than merit. Nor are they oblivious to their good fortune, having been raised by parents who put their privilege in perspective by hammering home this message: To whom much is given, much is expected.

“To me, that means not just living a life of leisure but living a life of purpose,” Chris says.

And giving back. Like their father and mother, Lindy, Chris and Michael support a range of educational causes, including the Evans Scholarship, which provides full college tuition and housing for high-achieving caddies. Sand Valley itself anchors a large-scale restoration project aimed at reviving the surrounding region’s native ecology.

The brothers’ quest to build world-class courses is shot through with an egalitarian streak. At the three sites they’re pursuing in other states, they envision laying the groundwork for socio-economically diverse golf communities surrounded by national parkland — not gated real estate developments reserved for the wealthy. The inspiration is vibrant, golf-centric destinations like Dornoch and St. Andrews.

It’s a bold idea. The Keiser brothers have plenty of them.

“They have different styles than their dad, but they share his endless curiosity and openness,” says Ben Cowan-Dewar, a close family friend and a partner with Mike in Cabot, a golf development company with properties in Canada, Scotland, Florida and the Caribbean. “They’re not afraid to explore new ground.”

In personality, the brothers, both of whom are married with two children, complement each other. As the more conservative of the pair, Chris takes a cautious, analytical approach that Michael sees as a healthy counterbalance to his own inclination to act on intuition. Both also keep busy with projects of their own. In addition to Sand Valley, Chris remains more deeply involved in Bandon than does Michael, who runs on an energy that rarely rests.

One recent outlet for him was the renovation of the former Glenway Golf Course, a city-owned nine-holer in his adoptive home of Madison. Michael was the driving force behind the redo of “the Glen,” financing the work while thumbing through his contacts to call on help from experts, including Wisconsin native and two-time U.S. Open winner Andy North. Since reopening this past summer, the renamed Glen Golf Park has given locals a spruced-up course that doubles as a park and community event space. It is Michael’s passion project, but, until this afternoon, Chris, who lives in Chicago, had yet to see it.

As they make their way around the rebuilt practice grounds, Chris praises his brother’s work while trying to out-putt him, even if the contest is the opposite of heated. A photographer is on hand, snapping pictures. Chris and Michael smile, putt, smile some more.

An older golfer strolls by with a bag strapped to his back.

“Who are those two young fellows?” he asks. “The Keiser kids, eh?”

He pauses, then adds before moving on his way: “Well, please tell them that I say thanks.”