Golf is a much more simple game than most folks like to believe. Nowhere reminds of this quite like the charmingly rustic Lanark Village Golf Club. Nestled among the swaying pines and saw palmettos of Northwest Florida’s Forgotten Coast, this six-hole neighborhood course proves you don’t need much to enjoy the many charms of golf.

I’m sure there are equally low-key golf experiences scattered across America, but it’s hard to imagine any place topping this expression of minimalist ethos. Lying just across the road from the Gulf of Mexico, Lanark Village Golf Club is a testament to homemade golf.

To the hundreds of people who drive by each day, Lanark probably looks like a quaint bayside meadow, but those who look closer are rewarded. Red flags wave atop grassy knolls that serve as greens. Weathered concrete benches denote tee boxes and a plastic lettered sign reads “Public Welcome – $5 All Day.” It’s maintained by the small tight-knit community that lives there, and it sits on a former Army barracks, a wedge shot away from the ocean. It’s not fancy, but it’s definitely some kind of golf.

I’ve passed by this remote course many times, often smiling when I see one of the locals mowing the holes with a riding lawn mower. During regular trips down the Big Bend Scenic Byway, I’ve considered stopping in to play, but other coastal commitments have always kept me away. That is until recently.

While vacationing with my family at nearby St. Teresa beach, I talked my wife into letting me take an hour-long golf break. She obliged, but with a sharp eye on the clock — we had a full day of building sandcastles with our daughter ahead. Being only a few miles away, I was off.

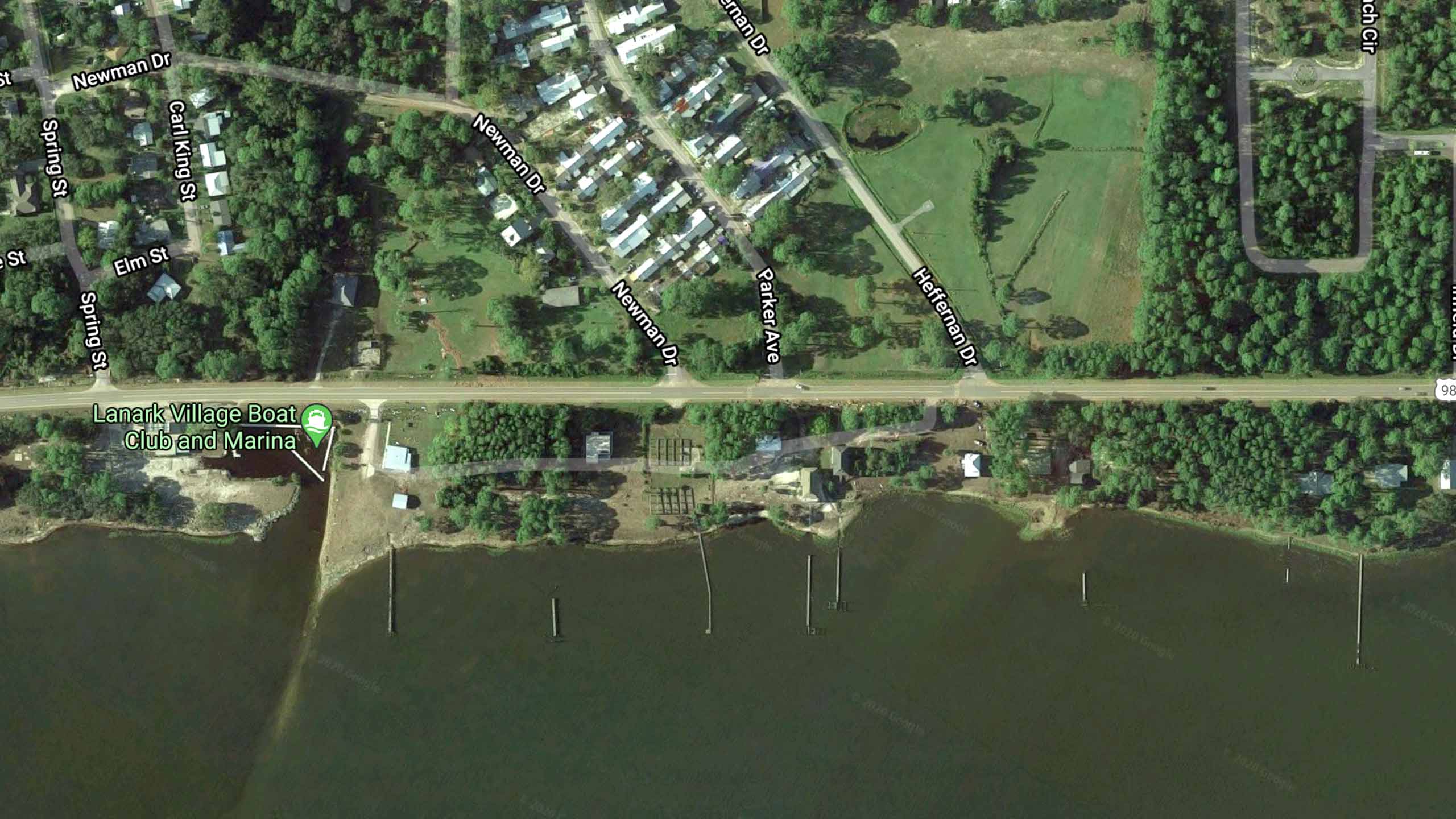

The short drive from St. Teresa to Lanark Village is one of the prettiest stretches in the Sunshine State. US Highway 98 hugs the coastline and showcases the wonders of Ochlockonee Bay, Alligator Harbor and the St. George Sound. It’s a part of Florida most tourists never see. The rural and heavily wooded seaside environment is reminiscent of the Jimmy Buffet deep track, “Tin Cup Chalice,” in which he sings of a place where the “shrimp boats tie up to the pines.” Many residents still try to make a living from the sea and the progress of man seems like it skipped over the area. There are still dirt roads here, most of them topped with oyster shells. You’re more likely to see a black bear eating from your garbage can than drunken spring breakers or retired snowbirds playing shuffleboard. Welcome to Franklin County. They call it the Forgotten Coast for a reason.

Lanark is just a pitstop for those who pass by en route to their favorite fishing hole, but there is more history than most folks care to know. Lanark was first settled in the late 19th century by a Scotsman with big dreams. His name was William Clark, and he was an early land speculator and developer who chased his fortune into the untamed swamplands of Florida. He named the hub of his signature development for the town he was raised in. The original Lanark lies just southeast of Glasgow, and its name comes from the Cumbric dialects of the early Brittonic languages and means “clear space” or “glade.” The moniker is just as fitting for the tiny fishing town in Florida.

Clark made a valiant attempt to establish a resort in his Lanark-by-the-Gulf. He built the Lanark Inn and a railroad to bring people to it. Tallahassee, the nearby state capital, was growing rapidly, and Clark saw an opportunity to create a coastal destination for those new Floridians. He and his companies were finding great success offering $1 train rides from the capital and extended stays at his Inn to enjoy fishing, hunting, warm springs and other spoils of the gulf. Had a late-night hurricane not rolled through in August 1899, the whole area may have developed into a household name, but instead the storm laid waste to Clark’s vision and the area remained remote for decades.

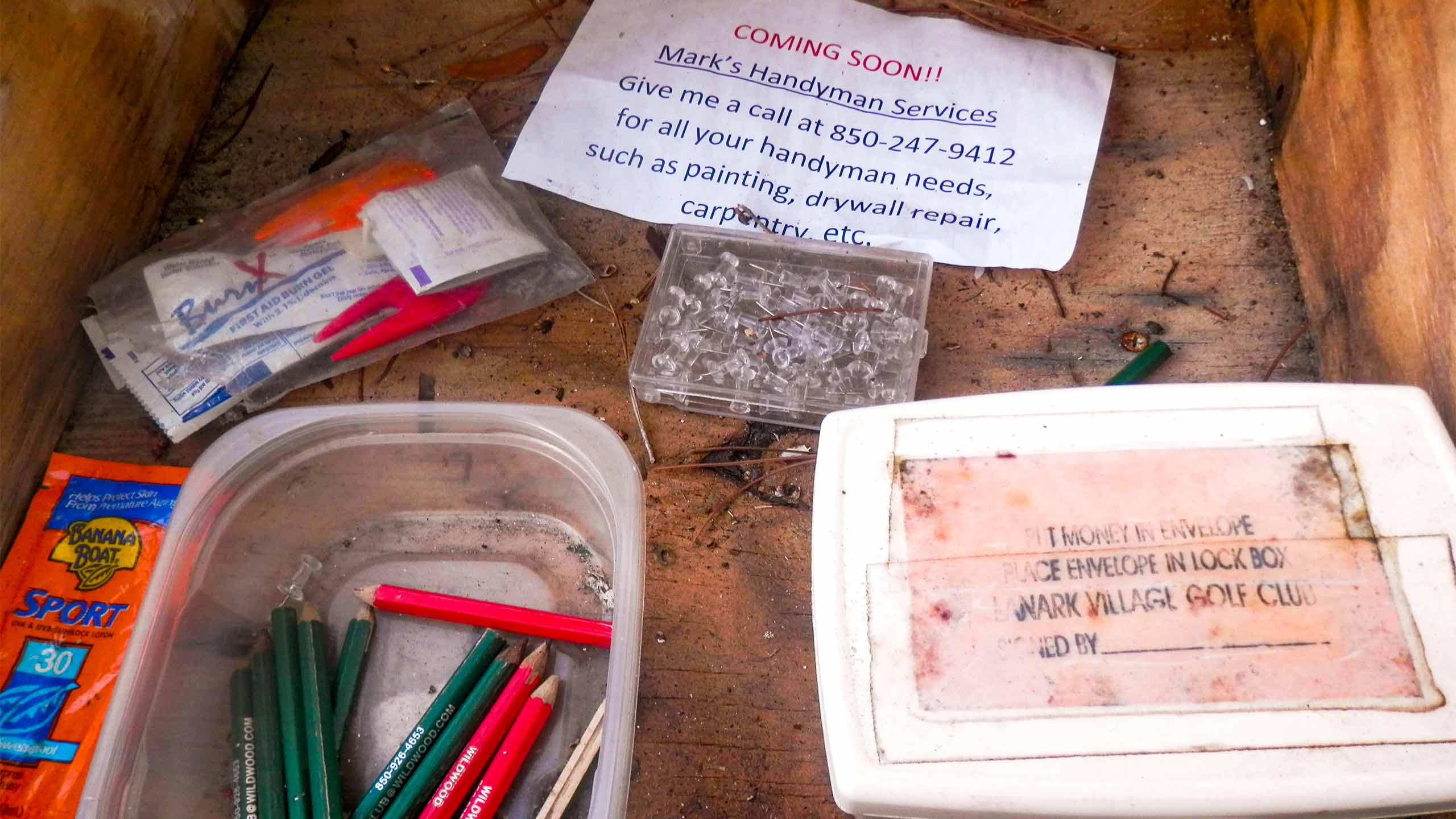

I arrived at Lanark shortly after first light on a beautiful Sunday morning. The late spring sunlight was breaking through the dense surrounding forest and the sound of boats carrying fishermen out to deeper waters broke the silence of the dawn. I pulled into a small grassy parking area near the first tee box and saw a wooden information kiosk that had long since been painted white. Hanging from a post was a small square sign with black hand-painted words exclaiming in all caps, “GOLF HERE.” A handful of notices were plastered to a pegboard to alert golfers of some basic but important information, including the daily fee and the $50 annual membership deal for residents. Beyond the kiosk the quiet street was lined with the cars and trucks of the Lanark homeowners. There were plenty of people in the village that morning, but sleep appeared more popular than golf.

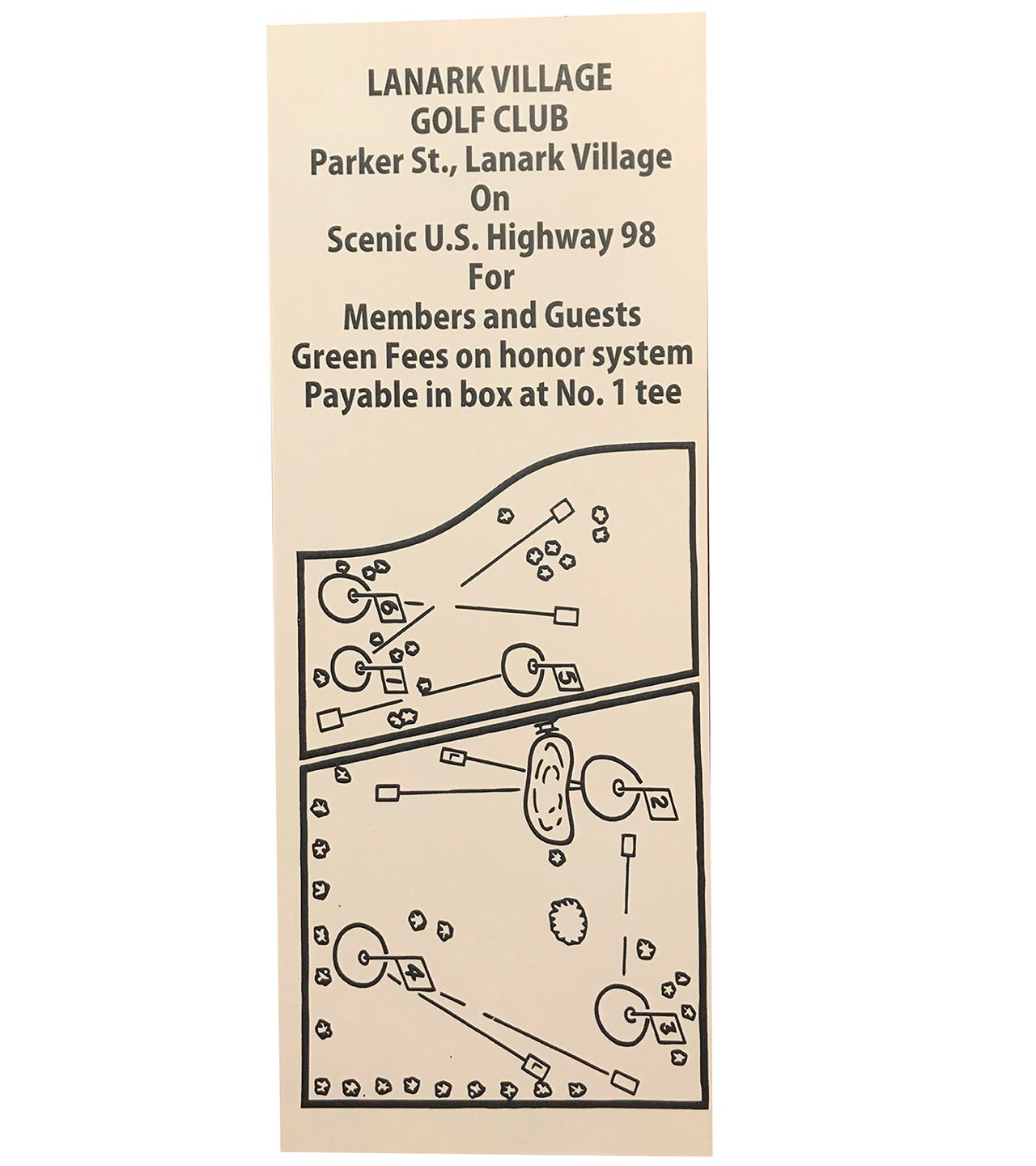

I had hoped to find the course without crowds, as I wanted the freedom to explore. That was clearly not a problem at this hour. With no line, no tee times, and no real structure beyond an honor box for my greens fee, this place was all mine. I grabbed one of the black and white scorecards from a mailbox by the car park and consulted a small map with the routing. Lanmark Village can be a bit confusing to the untrained eye. With the course being mowed at one single height of grass, the pin flags waving in the gulf breeze were my only markers for each hole. The map helped keep me on track, even though I was there to get lost in the game.

The course is divided in two parts by a local street that services the neighborhood. There are three holes on each side. On one half lies the 1st, 5th and 6th holes. That pasture is decorated with a few sparse pines and slopes downward toward the highway, the surf and the horizon. The homeowners with this view are clearly the envy of their neighbors. Those homes form the boundary for the playing corridors.

The homes at Lanark Village are made of concrete blocks and are attached by shared walls. They look like Army barracks, because that is what they were originally built to be. Forty-two years after William Clark lost his dream to a hurricane, the United States Army came in with a new vision. The coastal communities of Franklin County were an ideal place to establish a secluded training camp for soldiers. This is where American armed forces prepared for the D-Day invasion of Normandy and the capture of Pacific islands like Iwo Jima.

The Pentagon decided the sleepy Lanark area and its desolate surroundings was an ideal location to prepare tens of thousands of soldiers for a global conflict. Sprouting up almost overnight, the Army created what it called Camp Gordon Johnston, although the soldiers sent there would eventually call it “Hell-by-the-Sea.” Training exercises happened all day and night, and soldiers faced the fury of both their commanding officers and the surrounding wilderness. Those encamped in and around Lanark faced live fire exercises, amphibious landing simulations, real bombs and poor living conditions. For many it was an upgrade to finally leave and head to war.

Today, the only noticeable remnants of Camp Gordon Johnston are the former officer barracks and a few dock pilings out in the gulf. Now those barracks are painted tropical colors and have boats parked out front. In the years after the war, a developer turned them into a small retirement community, converting the former Army station into a quaint place to live for folks who like to fish. The entire community is self-governed by an association and residents pitch in to take care of the common areas and shared spaces. The golf course is owned and maintained by the residents for their enjoyment.

The golf course at Lanark is a par 20 with four par-3s and two par-4s, or you can play it three times for an 18-hole par of 60. The par-4s are basically long one-shotters, but when you consider the “putting surfaces” it all evens out. The greens, like the rest of the course, are composed of a buffet of lawn grasses. Almost any putt that drops is the result of a highly favorable bounce. (There are some local rules to help ease those challenges. Players are encouraged to play ball-in-hand as long as they are in the primary cut of grass.)

Lanark has hazards in play as well (not to mention the snakes). The streets and highways are out of bounds, there is a manmade pond with a questionable bridge on the 2nd hole marked with red stakes, and a strangely placed helicopter pad offers wayward golfers a free drop. Just because the course is simple, doesn’t mean it’s easy. If you break par here, you’ve earned it.

There’s a lot to appreciate in the rudimentary course, and evidence of the hard work and care put into it is everywhere. Some yard tools were left leaning against a pine tree from a job likely abandoned at sundown the night before. Someone had once painted a retro-colored golf ball mural on the side of the maintenance shed, and a slew of exotic plants had been placed in some choice locations around it. A walkway by the pond was about to be paved again, there was clearly some serious weed-eater work taking place, and a number of the course signs seemed to have been recently replaced.

With no other golfers on the course, I made my way around Lanark rather quickly. The walk was pleasant and on a Sunday morning it felt much like a church revival for my golfing soul. It’s clear those who spend their time here are true believers in the game, and with each step around Lanark I was reminded of why I believed, too.

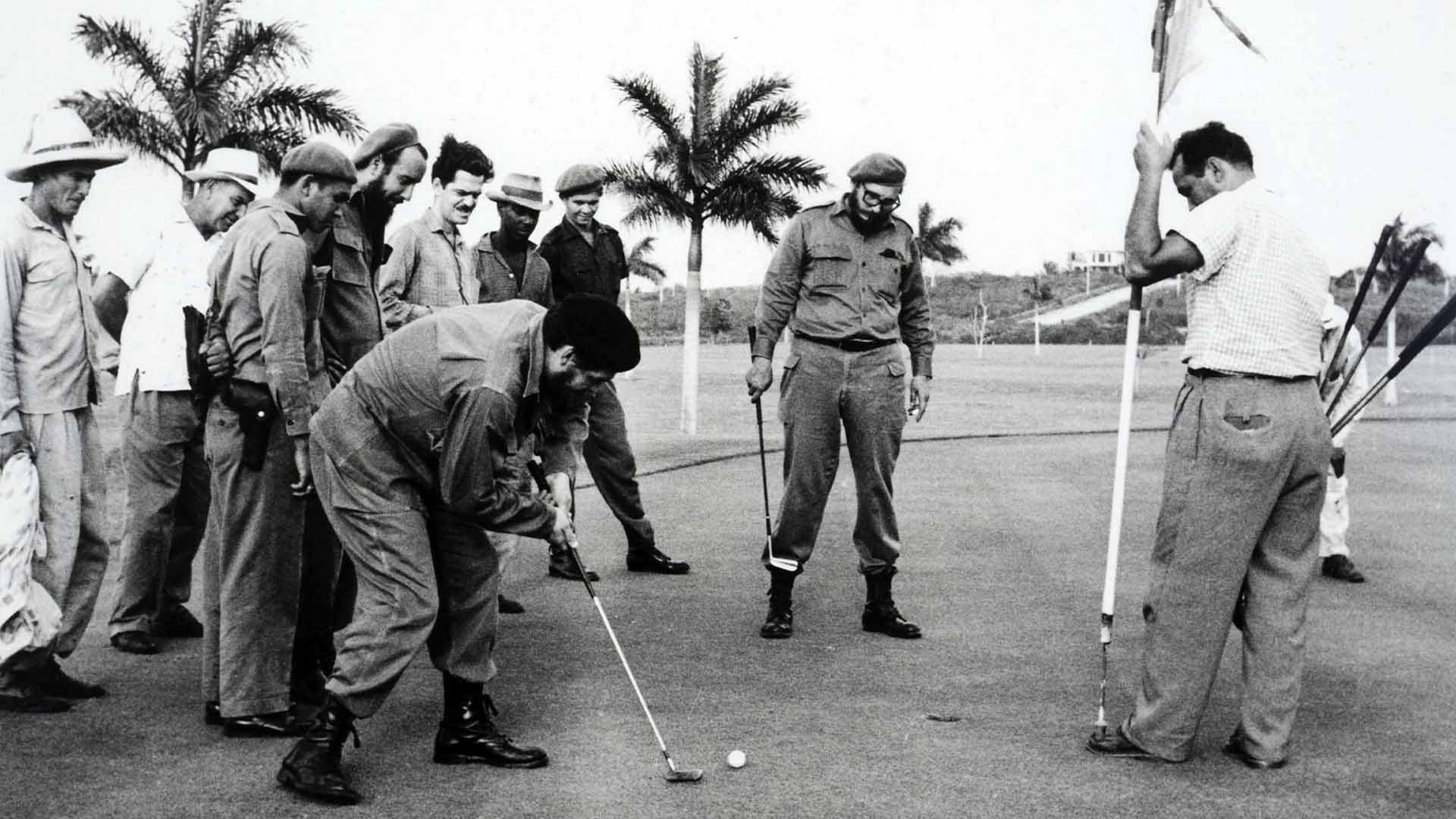

There is something romantic about this breed of golf. Perhaps it’s my affinity for how people make the game fit their circumstances, or maybe I’m just a golf addict and places like this still scratch my itch — the boiled down nature of it appealed to my golfing sensibilities. In some ways, Lanark harkens back to the earliest days of golf where the game was played by folks with funny looking sticks chasing a ball into a hole through otherwise useless land. Golf courses like this are few and far between in America, but to me this rendition is a symbol for the real spirit of the game. You have to really love golf to want to play at a place like this.

Keeping an eye on my watch, I finished my six-hole sprint with a few minutes to spare. I made my way back to the kiosk and proceeded to pay my freight for the day. Just as I pulled open the dusty honor box, I saw one of the locals — sporting a tank top and work gloves — pulling out onto the course riding atop his lawnmower. He waved at me and I at him. For a minute I was jealous of what he had. After a riveting Sunday morning walk, it was time for me to get back to sandcastles and popsicles by the beach. Watching the dedicated man start his work for the day, I decided to slip a few extra bills in the course’s collection plate. For golf like this to work, everyone has to contribute.

Jay Revell is a golf writer and public affairs professional living and working in Tallahassee, Fla., where he is a member and historian at Capital City Country Club. You can view his personal website here.