Published in 1976, The World Atlas of Golf should be a cornerstone of any golf architecture library, and maybe its finest feature is contributing editor Pat Ward-Thomas’s article, “Elements of Greatness: A Classic Course.”

Remaining true to each actual hole number (a No. 1 had to stay a No. 1, a No. 2 a No. 2 and so on), Ward-Thomas created an ideal 18, picking one hole from famous courses worldwide.

“Many may disagree with the composition of the course,” he wrote, “but nobody could fairly dispute that it would call upon a golfer to demonstrate skill in every part of the game; that it embraces the quality of exceptional design, and much of the beauty with which golf is blessed; that it would command respect from the mighty and be a great deal of fun for anyone to play.”

Mission accomplished, and brilliantly so: Ward-Thomas rightly focused on the quality of each hole as well as how those holes would relate to one another. It was an eye-opening read the first time and remains just as entertaining the hundredth time. Still, the book was published back in 1976—what about all the brilliant layouts built since?

Many people, myself included, believe that we’re living in a second Golden Age of course design, so it seemed only fitting that my homage to “Elements of Greatness” stick to places built post-World Atlas of Golf. As it’s meant to be a celebration of modern design, this list is restricted to one entry per architect, to acknowledge as many leaders in the field as possible. Also worth noting: 14 of these 18 holes are accessible to the paying public, a telling sign of progress.

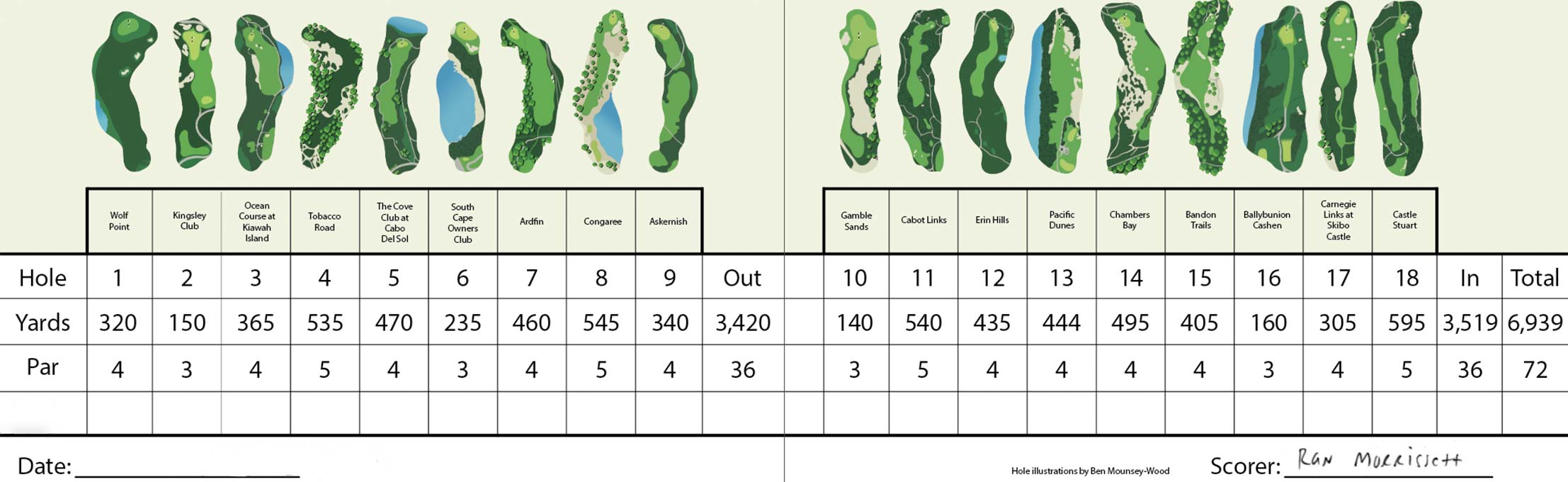

Hole No. 1: Wolf Point

Port Lavaca, Texas — Par 4, 320 Yards

Architects: Mike Nuzzo with Don Mahaffey

Why it’s great: A wide but strategic fairway provides the perfect getaway for an opening hole.

Overview: Ask four golfers why they like a hole and you’ll often get four different answers, but every (sane) golfer agrees that a wide fairway is the ideal way to start a round. Old Tom Morris taught us this lesson at St. Andrews; at Royal Melbourne, Alister MacKenzie perfected the notion of gaining advantage from a particular spot in a sea of short grass.

America’s widest first fairway, and one of its smartest, resides at Wolf Point, a course originally built for one man on his East Texas ranch that has developed a cult following among design aficionados since its 2007 opening.

A lake sits off to the left, the rest of Texas is to the right and the golfer finds himself staring at a fairway 240 yards wide. To miss it would bring shame, and yet, sure enough, the more you position the drive toward the trouble left, the better the angle of approach to most hole locations given the green’s predominant right-to-left cant.

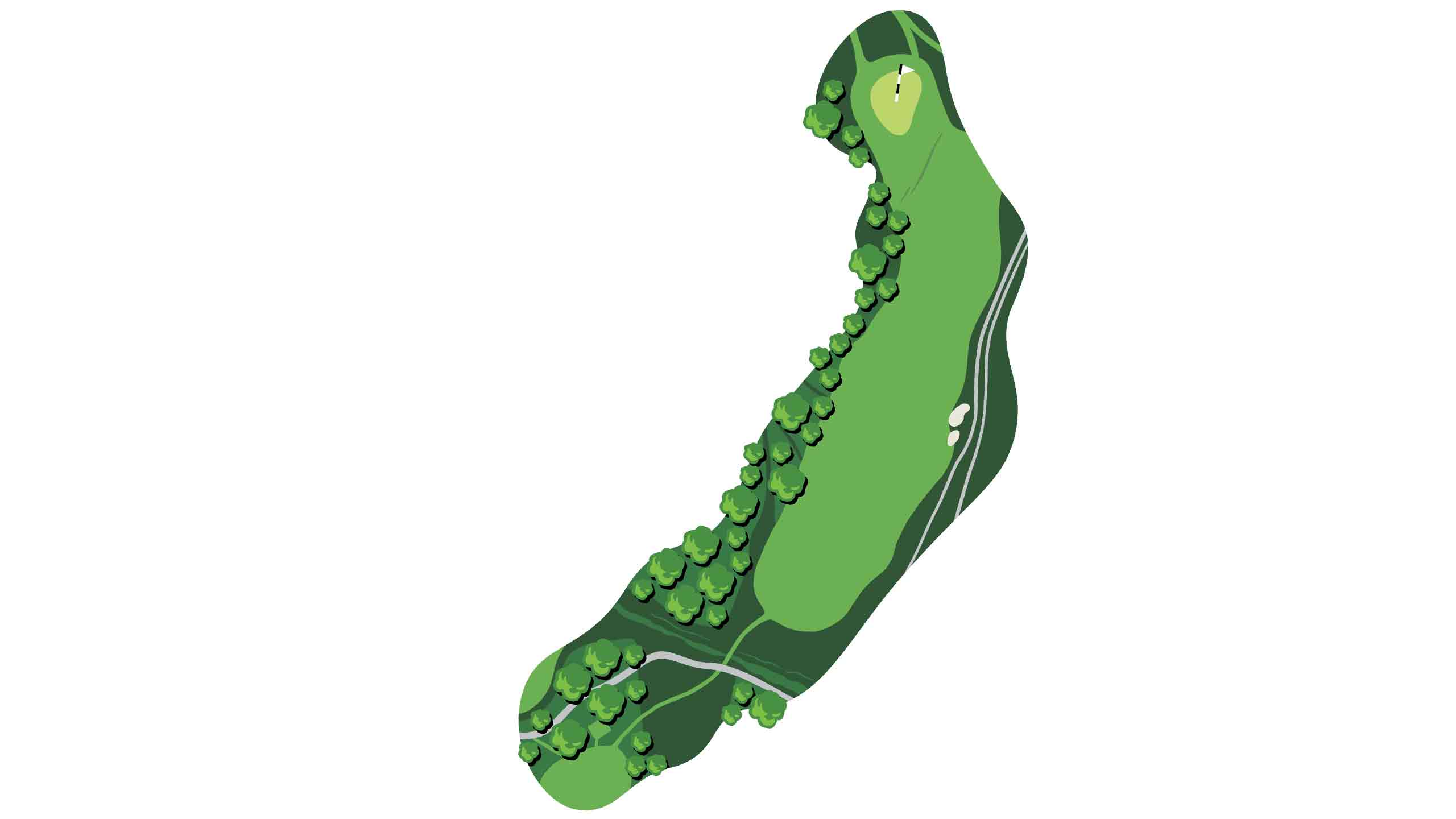

Hole No. 2: Kingsley Club

Kingsley, Mich. — Par 3, 150 Yards

Architect: Mike DeVries

Why it’s great: An ultra-precise par-3 shot is the perfect follow-up to a wide-open starter.

Overview: People who study golf’s pace of play—yes, there are such people—pooh-pooh the idea of a reachable par-5 or a par-3 early on either side, holding forth that such holes cause play to back up. My experience says that the opposite holds true, that both hole types invariably spread out play.

Regardless, Mike DeVries routed this one-shotter along the top of a ridge, with the narrow green naturally falling off on both sides toward either deep bunkers or, worse still, thick fescue grass. The green, at 38 yards, is much deeper than it is wide (just nine yards at the front).

Yard for yard, this may well be the hardest hole on this entire Dream Course. More important, the juxtaposition of its intense call for precision against the freewheeling, spacious opening hole is simply too delicious to pass up.

Hole No. 3: Ocean Course at Kiawah Island

Kiawah Island, S.C. — Par 4, 365 Yards

Architect: Pete Dye

Why it’s great: Green complexes this good don’t need bunkering.

Overview: Pete Dye did the game a huge favor when he reestablished the popularity of the short par-4. A 1963 trip to Scotland cemented his fondness for such holes, and this one might well be his finest. The fairway offers plenty of width; when the pin is front-left, the golfer aims right off the tee and vice versa. The merciless, bunkerless green is nothing more than a knuckle perched some five to seven feet above its surroundings, and its relative flatness provides no help in stopping approach shots.

Notably, when the breeze is off the Atlantic and into the player, the 3rd plays easier than when the wind blows offshore and the hole is downwind, as the already small, 3,920-square-foot green becomes even more elusive. Golf is more interesting to more people when accuracy and finesse trump brute strength, and it’s fascinating how a short hole with a tame putting surface can do just that.

Hole No. 4: Tobacco Road

Sanford, N.C. — Par 5, 535 Yards

Architect: Mike Strantz

Why it’s great: A great hazard you can challenge but recover from if you miss.

Overview: The dearly, too-early departed Mike Strantz left behind a small portfolio of nine original works that range from intimate to muscular. His designs resisted stereotyping except for one feature: He adored the button-hook par 5, meaning a hole that swings around a great hazard. Tobacco Road in fact features two such holes, this one and No. 11.

The latter plays around the deepest hazard in North Carolina, but the 4th was chosen for the grace with which the fairway tumbles and connects to the green. Also, the great hazard being more human in scale, at six feet deep, tempts golfers into greedier tactics than the hazard at 11, which is three times deeper. Hazards from which you can recover are more enticing, and therefore interesting, to challenge than water features like lakes and ponds, which are overly penal with no hope of recovery.

Hole No. 5: The Cove Club at Cabo Del Sol

Cabo San Lucas, Mexico — Par 4, 470 Yards

Architect: Jack Nicklaus

Why it’s great: A study in keeping the foreground “quiet” so the background can sing.

Overview: Standing on this elevated tee, with the distant flag flapping against the Sea of Cortez, it’s easy to understand why Jack Nicklaus maintains that golf is best appreciated played downhill. A lateral hazard runs the length of the hole along the right, while a shoulder from the hill protrudes in from the left. The closer the golfer hugs the lateral hazard, the better the optics for the approach shot to a green intensely connected to the sea. The putting surface starts off glued to the ground front left but gradually rises as it angles away to the right. Brave is the player who chases after back-right flags, as the short grass surrounding the green is only too happy to whisk balls away. No bunkers required, and at high tide the water can get as close as 15 yards from the green—the light touch of salt spray can make even the most concentrated golfer back away from a putt.

“What I think Ran likes about No. 5 is that it’s very picturesque, with an elevated tee that brings the entire hole—and the ocean sitting behind it—into view. Framed by a hill on the left and an arroyo on the right, the hole plays downhill to a bunkerless green. We worked hard to get the green as low and as close to the ocean as possible. It’s a strong hole. A nice hole, just one of many at Cabo Del Sol.”

—Jack Nicklaus, contributing editor

No. 6: South Cape Owners Club

Namhae Island, South Korea — Par 3, 235 Yards

Architect: Kyle Phillips

Why it’s great: Every course needs a “heroic” moment.

Overview: One sacrosanct rule in architecture: There are no rules. It’s easy to wax poetic about the ground game, as witness our prior hole; sometimes, though, it’s mighty rewarding when the architect demands that the player simply hit the damn shot needed. Such exemplars—think, No. 12 at Augusta National or No. 16 at Cypress Point—create the sport’s most thrilling, indelible memories.

This South Korean beauty replicates the latter’s heart-pounding excitement of launching a long iron off a cliff and over the pounding surf. The jagged cliff-line proved ideal for Kyle Phillips, who routed three of the course’s one-shot holes along it. He artfully arranged the tees here to make the shot palatable for as many skill sets as possible, but most players can’t help but have a crack from the tips, so compelling is the heroic carry. Though the setting steals the show, the rolling green itself is also full of character.

Hole No. 7: Ardfin

Isle of Jura, Scotland — Par 4, 460 Yards

Architect: Bob Harrison

Why it’s great: There’s an obvious shortcut off the tee—but is it the right answer?

Overview: Should there be a set way to master a hole or many? The 7th at Ardfin, opened in 2016 and criminally under the radar, is an example of posing a conundrum not easily solved. The straight line from tee to green traverses broken ground; the crescent-shaped fairway is an inverted C to the right. Logic suggests hugging the inside of the curve to reduce the distance for the approach…yet that route often yields a blind shot. From the outside of the fairway, more is revealed but the shot is longer.

One rub for the downhill approach: The green follows the slope of the surrounding land, i.e., the putting surface cascades from front to back. Trying to get the ball to behave and stop on the correct part of the green—even on a rare calm day in the Inner Hebrides—is among the more exasperating yet thrilling tests this Dream Course poses.

Hole No. 8: Congaree

Ridgeland, S.C. — Par 5, 545 Yards

Architect: Tom Fazio

Why it’s great: An old-school nod to “using the ground.”

Overview: For golf architects as for rock bands, the early work often remains the most original. To Tom Fazio’s credit, three decades after his designs at Wild Dunes and Wade Hampton reestablished that the sport should be about fun, he was producing top-notch courses like Congaree and Gozzer Ranch.

Much of Congaree’s playing season occurs when its Bermuda fairways are dormant—and blazingly quick. This golf-for-golfers club doesn’t color or overseed the fairways: Ownership appreciates the ground game and understands that the new Bermuda grasses aid this approach. Fazio imbued this design with numerous cases whereby you hit to X to end up at Y, none so dramatic as here, where the thrilling challenge is to hit left of the green, avoiding all the trouble on the right and allow the 30-yard-long kicker slope to feed the ball down and onto the open green—a shot to savor for the thinking golfer.

Hole No. 9: Askernish

Askernish, Scotland — Par 4, 340 Yards

Architect: Martin Ebert

Why it’s great: It proves that super greens don’t have to be superfast.

Overview: Situated in the Outer Hebrides, Askernish has the distinction of being built this century over ground once occupied by a 19th-century course designed by titans Old Tom Morris and Horace Hutchinson. Course owner Ralph Thompson got the idea in 2005 to maximize the wondrous dunescape here on the Isle of South Uist and called in architect Martin Ebert and greenkeeper Gordon Irvine to carry out his vision.

The course has only four formalized bunkers, and that’s plenty given the rollicking land. Just four people maintain the course, and the greens don’t play as intended if they Stimp much above 8. Never mind: As a set, the green complexes represent one of the game’s finest collections, headlined by the 9th, where the putting surface is set at a 45-degree angle to play. A deep depression in front and a deeper one in back confound the golfer, making this wee two-shotter a position hole with teeth.

Old Tom and Horace would be proud.

“The approach is one of those shots where you wait with a mixture of hope and trepidation until it’s safely on the closely mown platform of the green, which has the most wonderful micro-undulations, full of hollows and ridges—busy but totally natural.”

Hole No. 10: Gamble Sands

Brewster, Wash. — Par 3, 140 Yards

Architect: David McLay Kidd

Why it’s great: Challenges the notion that the target must fit the shot.

Overview: You hear it all the time: The target should fit the shot. A short hole? The green should be small. While that can be true, a small target has the sometimes unwanted effect of focusing a golfer’s concentration. As Nos. 9 and 10 at The Old Course have demonstrated forever, large greens at short holes make getting a pitch close bizarrely vexing.

Leave it to the Scotsman David McLay Kidd to pick up on such a design cue. Though the green measures a whopping 13,119 square feet, its interior contours are superb and the desired birdie often proves elusive. Even more maddening is when a bogey surfaces because the golfer got out of position on this position hole. For such a short hole, the massive green provides an uncommon amount of hole locations, be it back left atop a plateau or to the right in a bowl guarded by a bunker. That’s called flexibility, people.

Hole No. 11: Cabot Links

Inverness, Nova Scotia — Par 5, 540 Yards

Architect: Rod Whitman

Why it’s great: A par-5 that keeps its foot on the pedal.

Overview: Too many par-5s lack merit by tolerating loose play. Either the drive or layup is a nonevent, or the pitch to the green uninteresting. Here, each shot builds off the prior’s success. Finding the sloping fairway off the tee is paramount as Rod Whitman routed the hole such that the second shot must scale a 30-foot bank or else you’re likely headed for a regrettable sequence of events.

The 72-yard-wide, thought-provoking landing area for the second is actually wider than the driving zone, debunking the myth that a classic three-shotter must progressively narrow. As the hole is uphill and generally into the wind, Whitman extends an olive branch with the high left side of the green complex maintained as tight fescue, so that players can deaden their approach and watch the ball trickle off the slope and drift toward the hole. Both Mike Keiser and Ben Crenshaw consider this among the best par 5s they’ve seen. Enough said.

Hole No. 12: Erin Hills

Erin, Wis. — Par 4, 435 Yards

Architects: Dana Fry, Michael Hurdzan and Ron Whitten

Why it’s great: The glories of natural topography.

Overview: Recent restoration work at several Golden Age designs, including Eastward Ho!, Moraine and West Bend, has highlighted how thrilling golf over glacial landforms can be. Same here with the 12th at Erin Hills, which captures the sensation of playing across tumbling landforms even when more than 1,000 miles from the nearest coastline. Its fairway heaves and plunges, and architects Dana Fry, Michael Hurdzan and Ron Whitten did well to leave the landforms alone and keep the machinery away. The world’s most distinctive holes are the ones that follow nature’s lead, as unlike man, nature doesn’t repeat herself.

I once wrote of No. 12, “This is a prime example of what people mean when they write about a well-routed hole over great land. Courses over more mundane land can’t compete with drama so deeply rooted in nature.”

Dare I say, those words still hold true.

“With its wild topography, which tumbles up and down huge contours, the 12th best captures the character of Erin Hills.”

Hole No. 13: Pacific Dunes

Bandon, Ore. — Par 4, 444 Yards

Architect: Tom Doak

Why it’s great: Aesthetic pleasure is a key part of golf’s appeal.

Overview: This hole was a no-brainer selection: Just look at the thing! With the coastline left, a stunning blowout dune right and skyline green ahead, it epitomizes the allure of golf at Bandon Dunes Resort. Really, what more do you want? What most players don’t realize, though, is that this picture-perfect hole was a late addition to Tom Doak’s routing. As he explains in his new book on routing courses, Getting to 18, Doak originally had several holes routed on land that ultimately was used by David McLay Kidd for the Bandon Dunes layout. Thankfully, owner Mike Keiser kept gobbling up land to the north and presented Doak with the opportunity to include the parcel that houses the 13th into the final Pacific Dunes routing.

Unlucky 13

Built in 1988 in Northern Michigan, Tom Doak’s first design, High Pointe, now lies fallow, but those lucky enough to play it won’t forget the experience. The 430-yard, par-4 13th was as good as it gets: a downhill two-shotter to a green that fell away to the back left. Capping off a grand hole with a bland green in the name of “fairness” proved flawed thinking whose time would soon pass, thanks in part to Doak, who went on to earn fabulous sites and build even better courses but arguably has yet to build a hole that clearly surpasses this marvel.

Hole No. 14: Chambers Bay

University Place, Wash. — Par 4, 495 Yards

Architects: Robert Trent Jones Jr. with Bruce Charlton and Jay Blasi

Why it’s great: A dogleg that tempts — as it should.

Overview: At the heart of great architecture lies the temptation to attempt something to gain an advantage for the next shot. The dogleg is among the most time-honored of the myriad ways to present such a puzzle, and this one is among the best.

From an elevated tee, the golfer can readily grasp the risks and rewards of hugging or even cutting off the dogleg by carrying as much of the sandy waste as possible. A small central hazard of the sort far too infrequently found in modern architecture must be avoided as the hole elbows from right to left. The golfer then faces a hugely appealing approach thanks to the fescue fairways, whereby a low bullet draw can run forever toward a bank along the green’s right that helps feed the ball toward the hole. A sprawling bunker complex runs tee to green along the left and exemplifies Robert Trent Jones Jr.’s artistry—no surprise from a man who takes pride in composing poetry.

Hole No. 15: Bandon Trails

Bandon, Ore. — Par 4, 405 yards

Architects: Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw

Why it’s great: A truly sublime and thoughtful green complex.

Overview: Every course has a shortfall, and so does every Dream Course. Yes, it’s criminal that no hole from Sand Hills nor Friar’s Head appears in this compilation. Blame Coore & Crenshaw, not me: They’ve provided too many dazzlers from which to choose!

A diagonal cross bunker 130 yards from the green makes this a nervy drive; getting your drive close to, but not in, is a simple objective—except for the uncertainty of stopping a ball on these fescue fairways. What truly makes the hole is its fabulous found green site. Nestled in an amphitheater of dunes, the green appears as an extension of the fairway, climbing a false front and then rising to the rear: a postcard-perfect green complex with handsome bunkers carefully teased from the surrounding dunescape. Many people judge a course by the strength of its two-shotters, and one thing is without question—you have just played four straight sterling ones.

Hole No. 16: Ballybunion Cashen

Ballybunion, Ireland — Par 3, 160 yards

Architect: Robert Trent Jones Sr.

Why it’s great: A short par-3 with never-ending shot demands.

Overview: The Jones family patriarch, Robert Trent Jones Sr., acted as a bridge between the Golden Age and modern architecture. His reach of more than 500 courses is staggering considering his career mostly unfolded before air travel became routine. Many of his works were built on heavier-soil sites, so what a thrill it must have been to receive this commission in the early 1980s.

Not reliant on length, the 16th is prickly. Depending on the wind’s strength and direction, the tee shot may well have to be shaped and the trajectory definitely controlled. That’s what great golf is about, prompting better players to display the full arsenal of their shot repertoire. In this case, that takes place in one of the game’s most magical settings, with southwest Ireland’s fabulously massive sand dunes stretching up the coast and the sight and roar of the Atlantic just left adding to the drama.

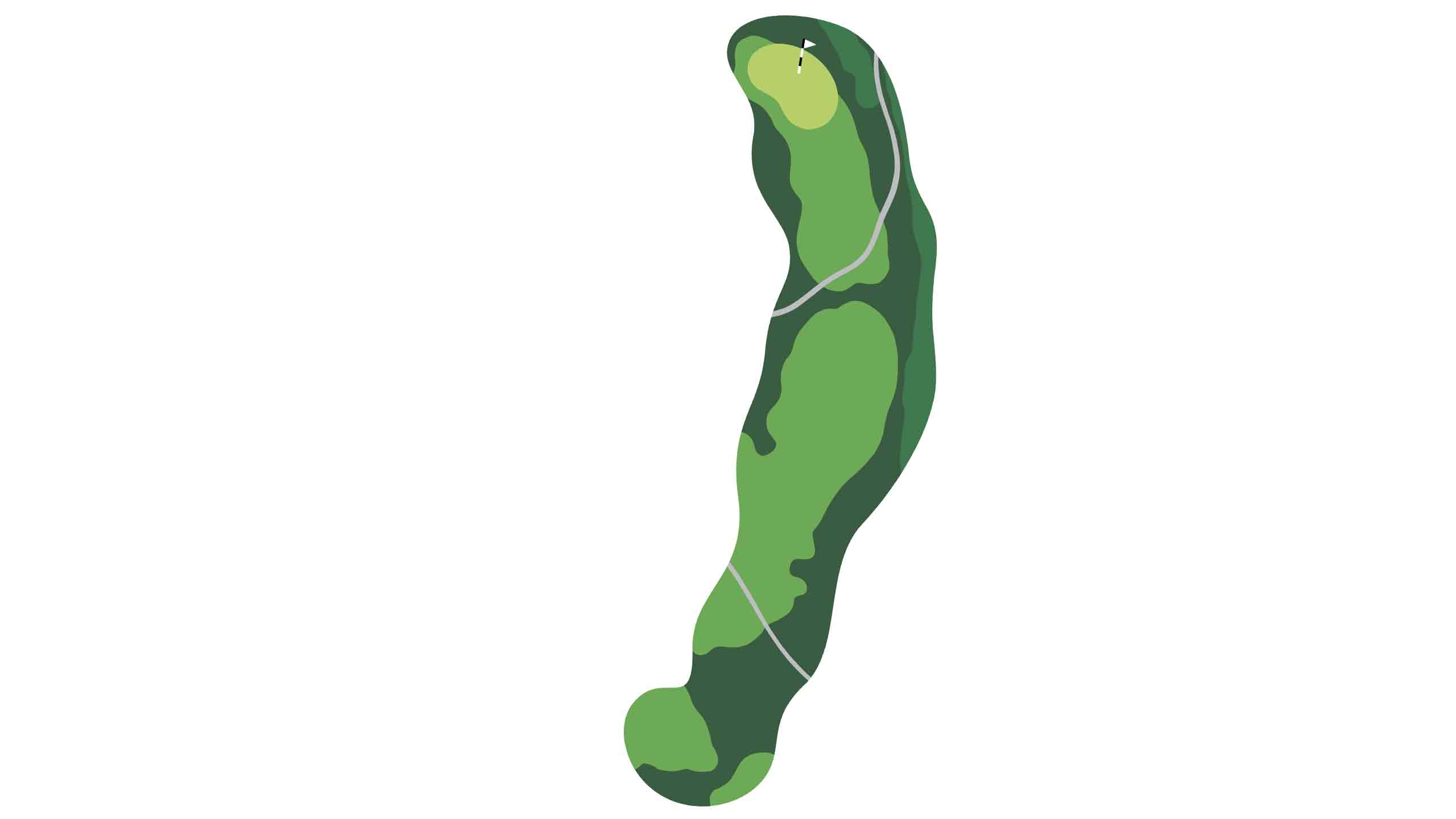

Hole No. 17: Carnegie Links at Skibo Castle

Dornoch, Scotland — Par 4, 305 yards

Architects: Donald Steel with Tom Mackenzie

Why it’s great: An impactful, drivable par-4.

Overview: In the first Masters, the nines were reversed, so the current Nos. 12, 13 and 15 lived on the first nine. Unimaginable! Where a hole falls in a round impacts its influence. Many thrilling short two-shotters come so early (including No. 3 at Augusta) as to limit their sway, but such is lay-of-the-land design.

Drivable short par 4s are the darling of modern architecture, and among the best late-round versions lives at Skibo. Situated at the end of a peninsula that juts into the Dornoch Firth, the 17th’s setting is impossibly gorgeous. Four deep pot bunkers litter the fairway; an angled green best accepts shots from the left, meaning that a tee shot needs to be aimed toward the firth and danger in order to open up the spine of the green for one’s approach. This teaser sealed the fate of the 1996 Shell’s Wonderful World of Golf match between Fred Couples (birdie) and Greg Norman (bogey).

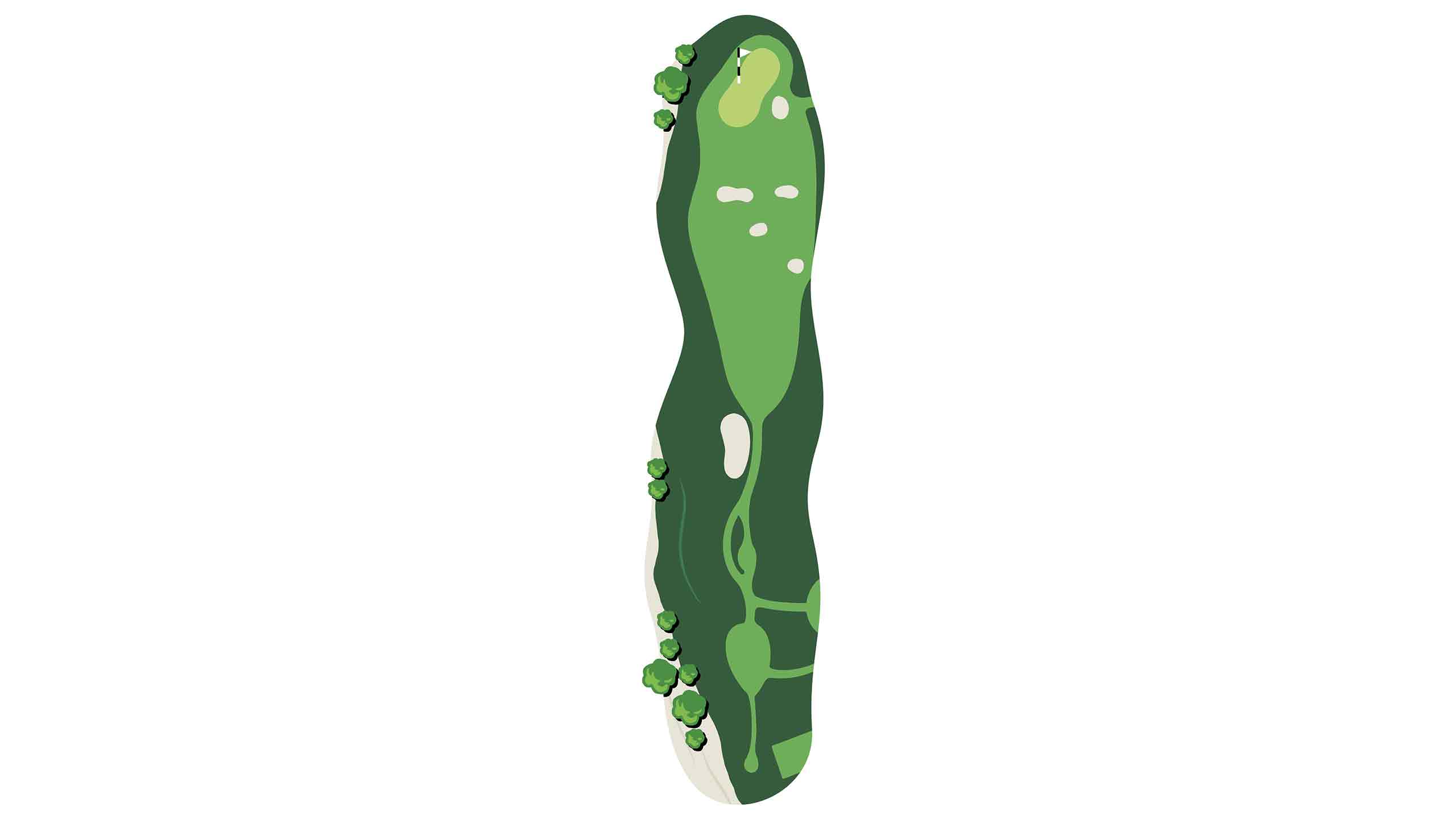

Hole No. 18: Castle Stuart

Inverness, Scotland — Par 5, 595 Yards

Architects: Gil Hanse and Mike Parsinen

Why it’s great: An exciting closer that makes you want to return to No. 1.

“At Castle Stuart, Mark and I put an emphasis on the visuals of the site and the choices a golfer can make, and with its sweeping views and multitude of options, the 18th really encapsulates those beliefs.”

Overview: A home hole has two prerequisite duties: pose interesting questions to suitably conclude a match, and make you itch to play again. Plenty of long par-4s do that (Harbour Town, Winged Foot’s West), but a half-par hole to the easier side (Pebble Beach, St. Andrews) does a better job drawing a player back.

Few perform their functions as well as the closer at Castle Stuart. Watching Scottish Opens here have been fascinating. One day, this hole is driver, wood, mid-iron; the next day, driver, mid-iron! Such elasticity doesn’t come by chance. The fairway cascades downhill, and its artful contours make a huge difference in where a tee ball finally ends. Under favorable conditions, golfers relish a crack at the green in two over broken ground and past bunkers. Otherwise, the fairway left of such trouble provides the safe passage—and lends the hole the coveted virtue of playing well for all players in all conditions.