2025 CJ Cup Byron Nelson payout: Purse info, winner’s share

2025 CJ Cup Byron Nelson payout: Purse info, winner’s share

New USGA, R&A report asserts distance gains hurting golf, stops short of enforcing solutions

Not everybody loves the long ball.

On Tuesday, the United States Golf Association and Royal & Ancient Golf Club took their firmest stance to date in regard to distance by declaring their conclusions from their long-awaited Distance Insights Project.

At 13 pages, the sharply worded report distills oceans of data into a summary of what the governing bodies perceive to be golf’s distance problem, assessing where the game has been, where it is and where it’s headed, as well as where it ought to go for its own good.

Exactly how to get there is another matter.

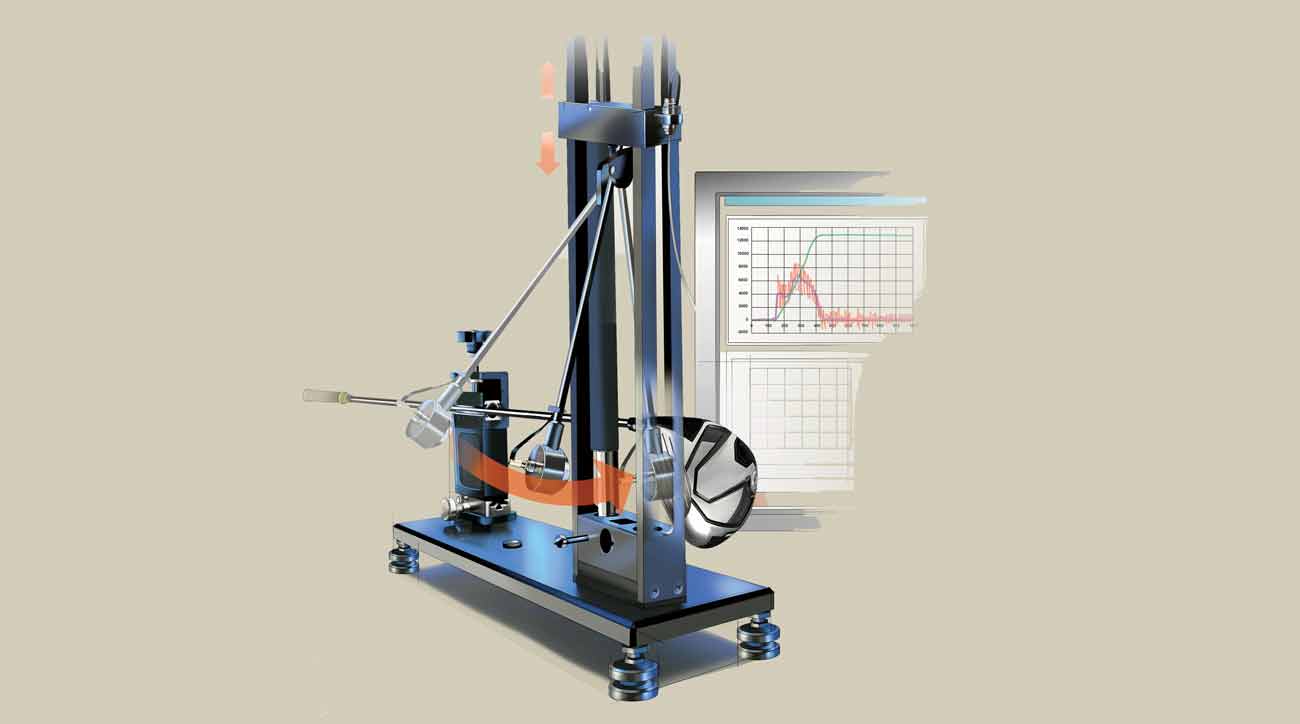

The report does not present solutions, but it hints at possibilities — including potential of new conformance tests for clubs and balls, and the adoption of a local rule that would allow courses to require limited-flight equipment — while laying out a blueprint for finding answers.

Under that plan, the USGA and R&A will produce, within roughly the next 45 days, a list of research topics for clubs, balls and other distance-related matters: a roster of problems that they believe need solving.

That will initiate a deeper review phase, projected to last at least nine months to a year, during which the governing bodies will welcome input from equipment-makers, course owners and architects, tournament operators, superintendents: an industry-wide conversation, open to anyone with a stake in the game.

At the end of that period, the USGA expects to present concrete solutions.

No one can say for sure what those will be.

The only clear conclusion the game’s guardians have come to is that for the sake of its own future, golf cannot continue on its current distance path.

“The expectation of every generation that they’re going to hit it longer than the previous generation, we think that is taking golf in the wrong direction,” USGA CEO Mike Davis said in a conference call last week between GOLF.com writers and USGA executives. “And we do see some really good opportunities to mitigate these pressures.”

You might not know it from watching your weekend foursome, but distances in golf have long been on the rise.

According to the distance report, the data trail traces to the late 1800s, when elite players typically hit drives of 160-200 yards, maybe 220 if they flushed one. Between 1900 and 1930, as the gutta percha gave way to the rubber-core ball, the average for big hitters swelled into the neighborhood of 220 to 260 yards, with the Cameron Champs of the era topping out around 290. Subsequent decades brought more of the same, as advances in equipment, agronomy and training, coupled with the growing athleticism of golfers, stretched distances ever farther, sometimes gradually, other times dramatically. By the end of 2019, the average drive of the 20 longest hitters on the European and PGA tours was 310 yards.

This story isn’t just true for Tour pros wielding driver. A similar theme applies to other groups of golfers and throughout the bag.

In many ways, it has been good fun.

ADVERTISEMENT

Distance wows spectators, bedazzles TV broadcasts and confers bragging rights in friendly outings. In many other ways, it has been good business. Distance sells equipment and swing instruction. It powers long drive circuits. It populates the pages of golf magazines.

But distance poses problems. Longer shots have led to the lengthening of many courses, while leaving others in the dust. Distance has stripped the intrigue out of many layouts, overwhelming their strategic challenge and making them unviable for competitions, or simply less enjoyable for everyday play.

As for those longer courses, they strain resources, an economic and environmental burden. They require more water and chemicals. They cost more to build, renovate and maintain, tightening margins that are already often razor-thin.

Then there’s this: Longer courses also slow down play.

For every Tour pro who can knock it to the moon, there are thousands of shorter-hitting everyday golfers, playing from tees that are too much for their games.

That’s the long and short of the distance problem. It works both ways, across every level of the game. And all signs show that the trends of the past century-plus are destined to continue.

That, anyway, is how the governing bodies see it. Enough is enough, their Distance Insights report asserts.

The release of the report raises many questions, including: Why now?

These are not new issues, and the governing bodies have not been blind to them. As far back as 2002, the USGA and R&A issued a joint statement sounding an alarm about the long ball.

“(Any) further significant hitting distances at the highest level are undesirable,” the statement read.

To tune into a Tour event today is to see what kind of effect that had.

The difference now, Davis said, is that the USGA has hard data to back up its assertions, having spent the past two years collecting and analyzing the facts and figures that serve as the foundation of this new report

“We know that there are more pressures on courses than ever,” Davis said. “We know that many are operating in the red. The costs are going up, and they’re either borne by all golfers, or the course becomes financially challenged or not in as good a place as it once was.”

Any effort to curtail distance is sure to run up against entrenched interests. There is bound to be resistance from equipment makers, whose contributions to the Distance Insights Project was limited to sharing data (they had no say in the report itself). Many recreational golfers will also likely bridle. Hitting it too far is not their problem; more distance, not less, is what they want.

It doesn’t take a skeptic to forecast serious complications in the task ahead.

Davis emphasized that the USGA does not anticipate making drastic, across-the-board modifications.

“We will review the overall conformance specs for clubs and balls, and these specs will be both directly and indirectly related to hitting distance,” Davis said. “But we do not intend on revisions to the overall specs that will produce substantial reductions in hitting distances at all levels of the game.”

Nor, however, do USGA officials favor bifurcation — creating different sets of rules and equipment for different groups of golfers.

“One of the great qualifies of golf is that we play under a single set of rules,” said Thomas Pagel, the USGA’s senior managing director of governance. “It’s one of the strengths and virtues of the game and something we are steadfast in retaining.”

Arriving at new rules for equipment that would satisfy all interested parties seems a daunting prospect, to say the least. It’s difficult to picture. Easier to envision are tweaks to other areas of the game.

Take course maintenance and setup. Davis raised the possibility of new recommended standards for fairway mowing heights, as well as additional guidance on farther-forward playing tees. In the United States today, the average and median length of golf courses is 6,700-6,800 yards. The data shows that many golfers playing from that distance have little to no hope of reaching greens in regulation, a reality, Davis said, that “impacts enjoyment and pace of play.”

USGA officials stressed that they’re not out to force change down the industry’s throat (whether they’d have the power to do so is a separate issue). For instance, the possible adoption of a local rule that would allow courses or committees to require limited-flight equipment would simply be an option, not a mandate, Davis said. One of its goals would be to preserve the architectural integrity of older, shorter courses that are either unwilling or unable to lengthen.

“Maybe you have a course where people say, ‘We’re not hosting a Tour event, but wouldn’t it be neat if we could get our club championship the way the architect wanted it to play?” Davis said.

Additional opportunities exist, the USGA believes, in creating and promoting golf experiences better suited to the rhythms and demands of modern life: shorter courses in urban settings, say, or customizable routings that allow for faster rounds.

There’s plenty to discuss. The conversation, which is destined to be drawn-out and likely often testy, will begin in earnest sometime around mid-March, when the governing bodies set forth the specific problems they want to solve. What will come of these efforts is TBD, but USGA president Mark Newell said that the governing bodies already have a litmus test for their success.

“We don’t know what solutions will be arrived at, or what rules changes will come or when they’ll take effect,” Newell said. “But three years from now, five years from now, we’d like to see that we were able to bring stakeholders in golf along to accept the importance of looking ahead. This is not about taking the game backwards or taking things away from people. It’s about creating options and conditions that are good for golf on today’s courses and yet-to-be courses. If that happens, even if the effects aren’t felt until further in the future, that will be a positive result.”

ADVERTISEMENT