2026 AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am money: Total purse, payout breakdown

2026 AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am money: Total purse, payout breakdown

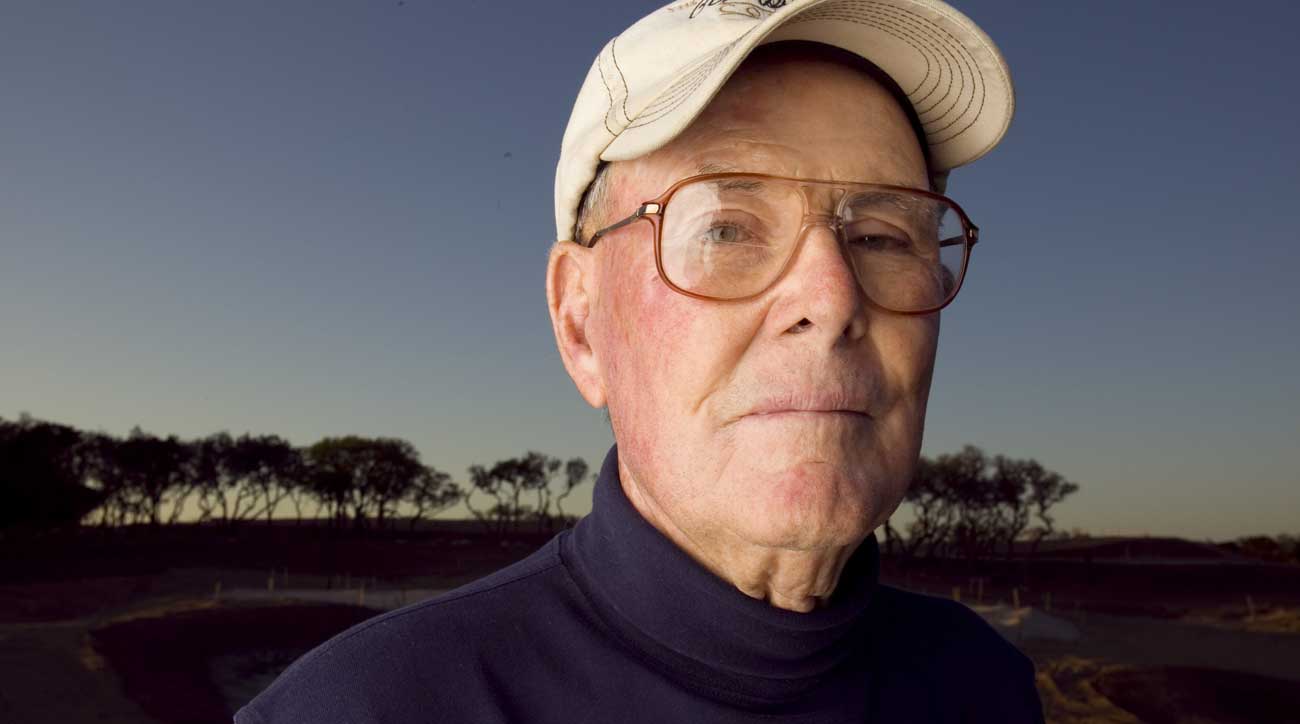

Pete Dye was an ageless wonder, and there will never be another course designer like him

This is a roundabout way to get into Pete Dye, but golf-course architecture is a round-about business. You could say that Robert Trent Jones begat Pete Dye and Pete Dye begat Tom Doak and right there you have 90 years of American golf-course architecture. You could also say that Robert Trent Jones — more than ably assisted by his wife, Ione — begat Rees Jones and his brother, Bobby. Both, like their father before them, are noted architects. Rees and Pete were close forever.

Rees is a friend of mine and on Thursday morning we were talking by phone but not about Pete Dye, whose death was announced later in the day. Rees was on speakerphone and after we hung up my wife said, “Rees sounds like he’s 30.” I have often thought something similar. Rees graduated from college (Yale) in 1963. He’s 78. He doesn’t look young but he sounds, thinks and acts young. His working life has a lot to do with it. It’s physically and intellectually vigorous. It keeps you moving.

Pete Dye was 94 when he went to that great pot bunker in the sky. (He wrote a book years ago called Bury Me in a Pot Bunker.) Rees and I got on the phone again Thursday night, to talk about Dye. Pete Dye was famously boyish. Boyish, impish, fun, in his drinking days and after he stopped, too. I asked Rees if Dye had ever lost those qualities. Dye had Alzheimer’s in his final years.

“He really didn’t,” Rees said. “He never got old. He loved to joke. He loved to tweak you. He loved to make you think.”

Rees would play with Dye at Gulf Stream, a private course in South Florida that Pete and his wife, Alice, had renovated. “The final time we played, I don’t know if he knew who I was but he knew when he made a par,” Rees said. “He made five pars and after every one he’d say, ‘I made a par!’ He was 92 and he shot 89.” Before he enlisted in the U.S. Army during World War II, Pete had been a schoolboy golf champion in Ohio.

Jack Nicklaus was 16 when he first met Dye. They designed Harbour Town Golf Links in Hilton Head together, in the late 1960s. “We would go over and take a look at it while they were building it,” Rees said. He and his father were building a course nearby. “We didn’t understand what he was doing. It was so low-profile.” The greens almost at the same height as the fairway. No big lips. Not a Trent Jones course, not an Alister MacKenzie, not an A.W. Tillinghast course. It was Pete Dye course, with Jack attached to it. Many players, good, bad and in between, love that course. The architects do, too, “because of the tight fairways and the small greens and the way the bunkers wiggle around them — there’s really nothing like it.”

The first time there was a Tour event there, in 1969, Arnold Palmer presented Dye with the gift of a lifetime. He won. “Guys tend to like the courses where they win,” Rees said. Over the next decade, Jack Nicklaus, Johnny Miller, Hale Irwin and Tom Watson won there. Every win was an enormous gift to Pete and his reputation. But he never built a course like Harbour Town again. His courses got harder and harder. He was going to show Hale Irwin and Co. who the boss was, even while he remained eminently likable and a fun hang.

When Deane Beman was looking for a somebody to build a course the Tour could call its own, he chose Pete. The land was a few hundred acres of choice North Florida swamp but Pete had a bulldozer. He didn’t find the Stadium Course in the land, to use the phrase Old Tom Morris always used. He dug it out of the muck. There were a lot of long days and nights, though good luck finding a nearby steakhouse in those days.

Fred Couples won there early, in 1984, and then won again there in ’96. Pete loved Fred but loathed how far he hit the ball — it was killing his creation. John Daly, the same. When you can drive it high and forever, like Daly did when winning the 1991 PGA Championship at Dye’s Crooked Stick course, you make every dogleg hole a straight hole. Four-seventy becomes a launched driver and a spinning sand iron.

In our conversation, Rees kept returning to Harbour Town, because it has always been so much fun to play and it never became obsolete. (Harbour Town and TPC Sawgrass are similar in that each course has 18 holes.) Rees’s other favorite Dye courses are the Teeth of the Dog in the Dominican Republic; Gulf Stream, minutes from the Dye’s South Florida home; the Honors Course near Chattanooga, Tenn.; Dye Preserve, also in South Florida; and The Golf Club, in New Albany, Ohio. He is less enamored of Dye’s big earth-moving projects like PGA West, “but they serve their purpose,” Rees said. “To sell real estate.”

In the early 1950s, after Robert Trent Jones got a big write-up in The New Yorker by Herbert Warren Wind, Pete Dye had the idea of getting out of the insurance business and into course design. Alice Dye, his young bride, was a top amateur golfer. “She asked Dad to hire Pete,” Rees said. “He never did.” But they talked, they compared notes, they very much did their own thing.

Robert Trent Jones took great inspiration from Robert Tyre Jones and Augusta National. Trent Jones did significant work there after World War II, and he built courses that were big: fairways as wide as airport runways, greens as wide as the White House lawn, bunkers as big as Jones Beach. Pete Dye wanted none of that. He was always his own man.

“Pete’s art was that he wanted to deviate, he wanted to do something different,” Rees said. Rees likes to look at the Kiawah course, in coastal South Carolina, just like everybody else. How can you not? It’s gorgeous! But in the wind, it can be unplayable. “He’s got these high, exposed greens, impossible to putt some days, but Alice wanted to look down and see the ocean.” You can see the ocean, all right. Whistling Straits is 18 postcards, too. Can you play it with one ball? Sure, if your name is Jason Day.

ADVERTISEMENT

“When the players criticized Pete, he said, ‘Thank you,’” Rees said. It told him he was doing something right. “Pete’s courses are hard. Hard and visually exciting.”

Writers and players came up with phrases for Pete Dye courses. Trying to hit a ball on a Pete Dye green “is like trying to keep a ball on the hood of a VW Bug.” This word-of-the-day invention followed Pete to his deathbed: Dyeabolical. You can’t sell tough-tough-tough today and you wouldn’t want to. People want courses they can actually play. But when Pete Dye was at the height of his powers, long after Harbour Town, torturing 90-shooters was considered sporting fun. It was an era and Pete Dye owned it.

If you look at photos of Pete Dye from anytime in his career, he looks like he’s having the time of his life. My wife and I went to Caso de Campo on our honeymoon and I played the Teeth course. (We bought black-market gasoline in Evian bottles from a caddie so we could explore the island during a gas shortage.) Dye had a spectacular thatched-roof house there and I remember various Dyes on the patio, enjoying the good life, Buckeye style. Big Jack and family, so generous to Pete on his Twitter feed, can tell you all about that. Steak, beer, jokes at your expense, the game on TV.

Pete would try things that nobody else would ever think of doing or certainly try to do, and he was successful at it. If there was a problem to solve, you solved it Pete’s way. In the end, Pete’s way usually turned out to be the right way.

— Jack Nicklaus (@jacknicklaus) January 10, 2020

The last time I saw Pete Dye was about decade ago. A friend and I were playing Gulf Stream. A man named Bill Beinecke was our host. (Mr. Beinecke was in his mid-90s and looking good.) Late in the round and late in the day, we spotted a man in a golf cart driving along the course, accompanied by a dog and ball retriever. Old Pete Dye, checking out his course. Old Pete, having himself a big time.

Michael Bamberger may be reached at Michael_Bamberger@GOLF.com

ADVERTISEMENT