Anybody who knows anything knows that Big Jack has six green coats. Those same people know that Tiger was stuck for years on four, Arnold’s number, but now has five. Something happened in the Tiger Era, at least for American golfers: The Masters rose in stature, for all manner of reasons. The elite club nature of the club. The magic carpet-ride course. The scarcity of tickets. The various club and tournament customs out of the Masonic Lodge playbook. The CBS theme song for its coverage.

Over the past quarter-century, how many American junior golfers have stood over downhill 8-footers and golf-whispered, “This is to win the Masters”?

It’s all a bit much.

As Jack Nicklaus, a member of Augusta National, has said on more than one occasion, “I always thought of the Masters as a nice little tournament.” You know, an invitational, like the mid-summer Member-Guest at your club. “The U.S. Open,” Nicklaus said, “was a championship. And because it was my country’s championship, it was the most important event to me.”

Nicklaus won his first U.S. Open in 1962, in a playoff over Arnold Palmer. He won two U.S. Opens at Baltusrol, in 1967 and 1980. He won the 1972 Open at Pebble Beach. That’s four. Willie Anderson was the first golfer to win four U.S. Opens and Bobby Jones was the second. Ben Hogan won four, too. Nobody’s won more.

Tiger’s won three, all on courses open to the public, which is fitting, as Woods grew up playing public courses. He won in 2000 at Pebble Beach, in 2002 at Bethpage Black and in 2008 at Torrey Pines, where he and his father, Earl, who had died in 2006, had logged many days together.

Fathers always factor in U.S. Open stories, or almost always. That’s why we know that Jack’s father, Charlie, worshipped Bobby Jones, and why we know that Jones’s father was called The Colonel. That Hogan’s father took his own life, thereby shaping the rest of his son’s. (Hogan and his wife, Valerie, never had children.) That Arnold’s father, Deacon, not a religious man, worshipped the National Open, and raised Arnold to do the same. (PTL that he won that one!) That Tom Watson’s father, Ray, had committed to memory all the Open winners by year and venue and Tom could never stump him.

How would we think of Tom Watson’s career without his lone U.S. Open win? Or Arnold Palmer’s, had he not won in 1960 in Denver’s thin air? His drive on the first, Saturday afternoon.

Sam Snead and Phil Mickelson are golf legends. But Snead went to his maker as the greatest American player never to have won the U.S. Open. At least for Phil there’s still hope. Of course there is: he hits bombs. The point, though, is that even in futility, the U.S. Open looms, and fathers as well. Snead’s father, Harry, built Sam’s first clubs himself, from tree limbs, as the story goes. Phil Mickelson Sr., a pilot and a good player, brought little Phil to San Diego’s public courses, and encouraged him to play lefthanded, even though the boy wrote with his other hand.

In U.S. Open stories, where there’s a son, there’s a father. Not always, but often. My father, who is 92, hasn’t played nine holes in his life, but when the U.S. Open was at Shinnecock Hills in 1986, an easy train-ride from our house, he wanted to come out and see what this whole golf thing, which so captivated his son, was about.

He was struck by Raymond Floyd’s tears in victory. All through that Father’s Day, Raymundo had seemed like such a tough customer. What my father realized is that solemnity is baked into U.S. Opens. He also learned, along with untold others, that Raymond’s father, L.B., was the longtime pro at the Army courses at Fort Bragg. Fathers and sons, fathers and sons, fathers and sons. This is heavy stuff. The U.S. Open doesn’t have a theme song.

Nicklaus’s win in ’62 galvanized our sports-loving nation, because Arnold and Jack were such different people, neither much like the other, except in the area of sportsmanship. The ’72 Open was the first held at Pebble Beach and Nicklaus’s win there elevated Pebble’s standing in ways that reverberate still today.

Dynamic duos: The only thing better than playing in a U.S. Open is having your son in the field, tooBy: Josh Sens

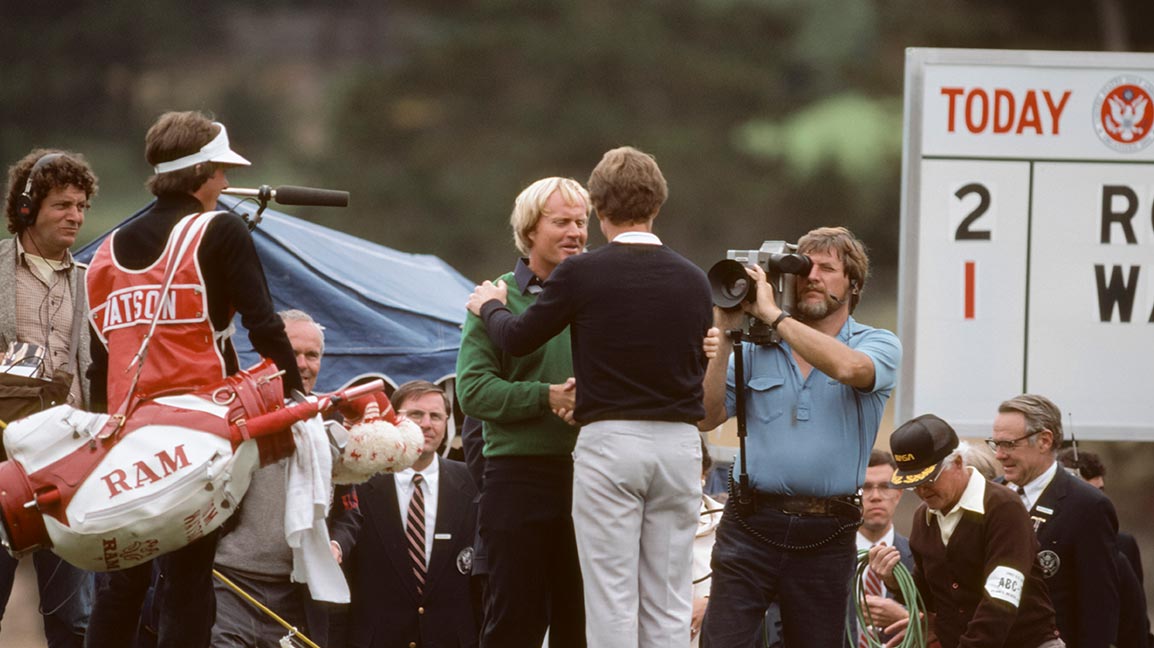

Ten years later, Tom Watson won the ’82 Open at Pebble, beating Nicklaus, who finished second by two shots. That win elevated Watson to iconic status. Nicklaus, the other day, did a USGA interview where he was asked to recall certain shots and moments from his U.S. Open from 1980. It is a testimony to Nicklaus’s mind that he can clearly remember so much of what happened there, 40 years later. His mind, and the occasion.

Big Jack would sign on for that second part, the occasion. He would tell you his memory is excellent for things he calls “impactful.” His four wins in his National Open, of course, were impactful. The two times he was the low amateur in the National Open? (He tied for second in 1960 and tied for fourth in 1961.) Those were impactful, too. The 12 (!) times after that he had top-10 finishes without winning? All, in varying degrees? Ring a bell for impactfulness for each of them.

And then, for Nicklaus, there’s another category: his son’s U.S. Opens. Gary Nicklaus played in his national championship twice. No, he didn’t make the cut either time, but how many people can say they played in even two U.S. Opens? And what a thrill for dad, for Jack, for any father. My son is playing in the U.S. Open. That’s about as good as it gets.