Before J.J. Spaun’s 64-footer? Mini tours, money games and a coach’s belief

Before J.J. Spaun’s 64-footer? Mini tours, money games and a coach’s belief

This 14-year-old leukemia survivor just beat odds of a different kind on the golf course

We could all use some good news right about now.

A bit of positive golf news would be welcome, too.

Dakota Cunningham, a sweet-natured 14-year-old with a rhythmic swing, has us covered on both fronts.

On April 2, Dakota was breezing through a round at his home course, Cherokee Valley Golf Club, in Olive Branch, Miss.

The sun was high. The wind was light.

On the 16th hole, a 135-yard par-3 with the pin tucked tight behind a front-right bunker, Dakota pulled a 7-iron, waggled, coiled and sent a gentle fade on a beeline for the flagstick.

“It was tracking all the way,” Dakota says.

The odds of making a hole-in-one are a distant 1-in-12,500.

But long odds are nothing compared to what Dakota had already overcome.

Nearly three years ago, Dakota’s father, Steve, was driving home from work when a call came from a doctor, who was also a neighbor and a friend. He was calling about then 11-year-old Dakota, who, suffering from a sore throat and a badly swollen neck, had just been to the hospital for tests.

The diagnosis wasn’t final, but the signs weren’t good.

The doctor urged Steve to get home quickly.

“I love you, man,” he added.

There wasn’t a whole lot more to say.

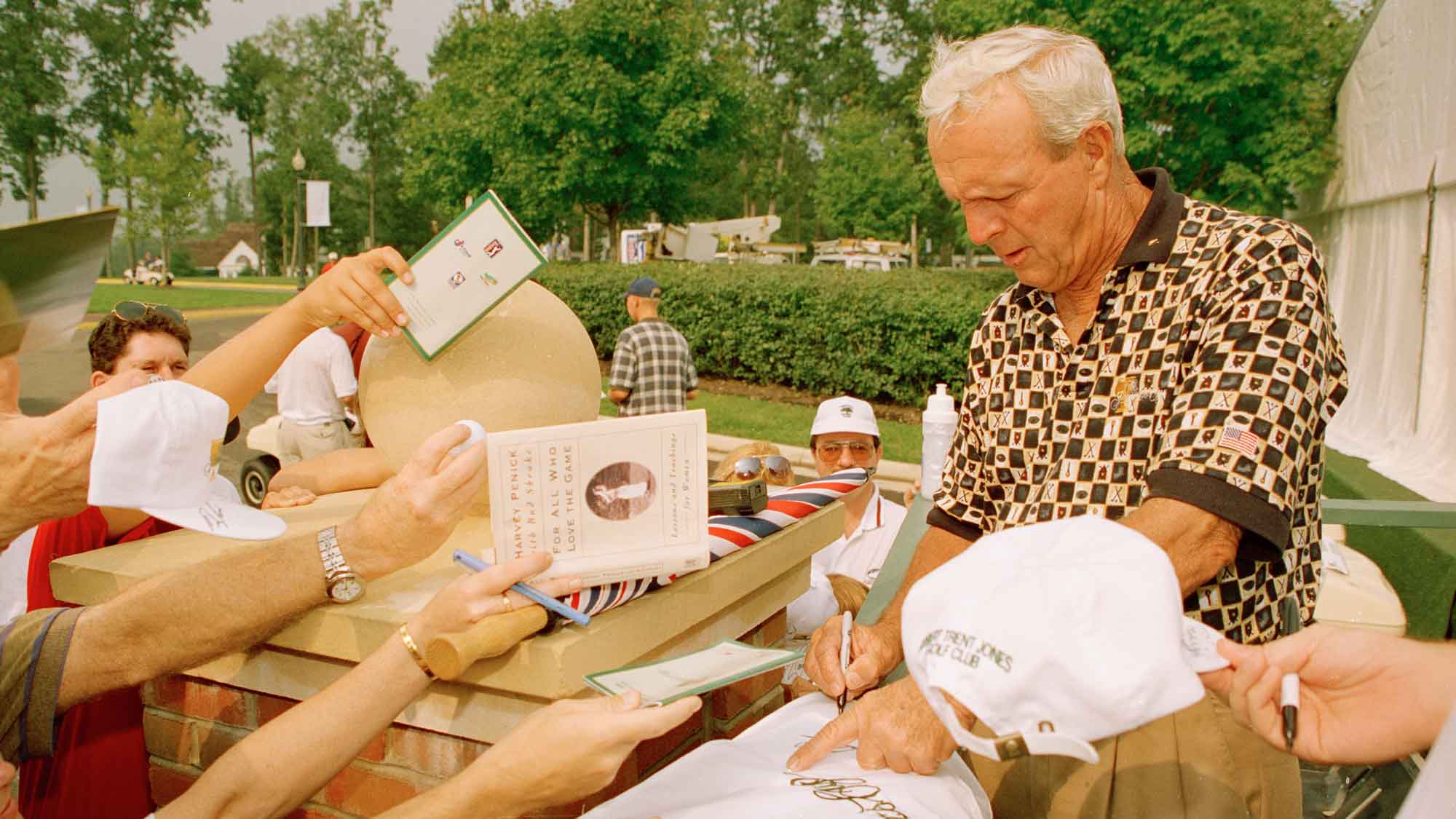

Almost from the time that he could toddle, Dakota was an active and athletic kid. A fearless snowboarder by age 4 (“First day on the mountain,” Steve says, “he was up at the top, pointing straight down”), he’d go on to earn a black belt in taekwondo. Golf was also in his childhood orbit, thanks to Steve, who, in his early 20s, had knocked around on the mini tours. There are photos of Dakota, at maybe 2 or 3, crawling while clutching a sawed-off fairway wood.

In grade school, though, Dakota started gravitating toward soccer. He loved playing goalie, embracing the responsibilities of a position that required decisive action and a firm command of the field. Steve and his wife, Tricia, Dakota’s mom, stood behind him all the way. Passions aren’t something you interfere with.

In May 2017, just days before the doctor’s ominous phone call, Dakota won a spot on the state soccer team, shining in a three-day tryout despite feeling fatigued. On the morning of the second day, he was so worn out that Tricia had to roust him out of bed. At a team picnic following the tryouts, Dakota was jogging toward the sidelines of a friendly scrimmage when Steve and Tricia noticed something. All the parents and coaches did.

“His throat was so big,” Steve says. “He’d lost his neck.”

At a preliminary checkup, their doctor friend said that Dakota’s lymph nodes were so severely swollen, they were pressing on his trachea, pinching his airway down to a few millimeters wide. A passage about the size of a coffee stirrer. That’s what Dakota was breathing through.

Further tests confirmed this, and much worse: Dakota had acute lymphoblastic leukemia, an aggressive cancer of the blood and bone marrow.

“In that moment,” Steve says, “our world just turned.”

It was breathtaking how quickly it happened, Dakota’s transformation from budding soccer star to cancer patient. The first specialists to see him were at Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital, just across the Mississippi River, in Memphis. But Dakota was soon transferred to nearby St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, one of the world’s leading lights in pediatric cancer care. St. Jude owes its origins to the late entertainer, Danny Thomas, who established the hospital with funds he raised as host of the Danny Thomas Memphis Classic, a tournament that morphed into the FedEx St. Jude Classic and, later, the WGC-FedEx St. Jude Invitational.

St. Jude was the patron saint of lost causes. But, all due respect to his holiness, “lost cause” is not a phrase in the Cunningham family lexicon.

The specialist in charge of Dakota’s care was Dr. Hiroto Inaba. At their first consultation, Dr. Inaba asked Dakota and his parents to raise their hands and vow to remain resolute.

“If you give me the next two-and-a-half years,” Dr. Inaba told Dakota. “I’ll give you 80.”

Like the cancer he was fighting, Dakota’s treatment was relentless and intense.

“There was so much chemo you couldn’t wrap your head around it,” Steve says.

The side effects were unforgiving. They included pancreatitis, drop foot and mucositis, an inflammation so painful that Dakota told his parents that it felt “like someone is pouring Tabasco down my throat and it won’t stop.”

ADVERTISEMENT

For Steve and Tricia, it was brutal bearing witness. Resolved to remain stoic to support their son, they discovered that it also worked the other way around.

“He was our strength because he was so strong,” Tricia says.

Just before the treatments started, Steve and Dakota had a frank conversation. Dakota’s first question was about soccer.

“Soccer is done, son,” Steve said.

“What about my hair?”

Dakota was no different than a lot of kids that way, always flipping his hair like a boy-band singer.

“The hair’s gone, son,” Steve said.

Dakota let that sink in.

“OK, let’s go,” he said.

Within weeks, he’d not only lost his hair but also he’d also lost 20 pounds, a young athlete reduced to a shadow of himself, relegated to wheelchair and then a walker and then to the point where his father had to carry him to the bathroom.

“Attitude is everything,” Steve and Tricia often said, a call to optimism that became a family motto.

Humor, too, became a way coping.

“We probably joke about things you shouldn’t,” Steve says. “But we were making jokes about how many times he’d thrown up in a day.”

As his health slowly improved, Dakota turned his mind to sports. Soccer was a no-go. He could barely walk, much less run. So, he grabbed a golf club and started chipping. There is video of this, a slim-downed Dakota, still unsteady on his feet, swinging, smiling showing delicate touch.

“It was kind of physical therapy at first,” Dakota says. “Then I fell in love with it.”

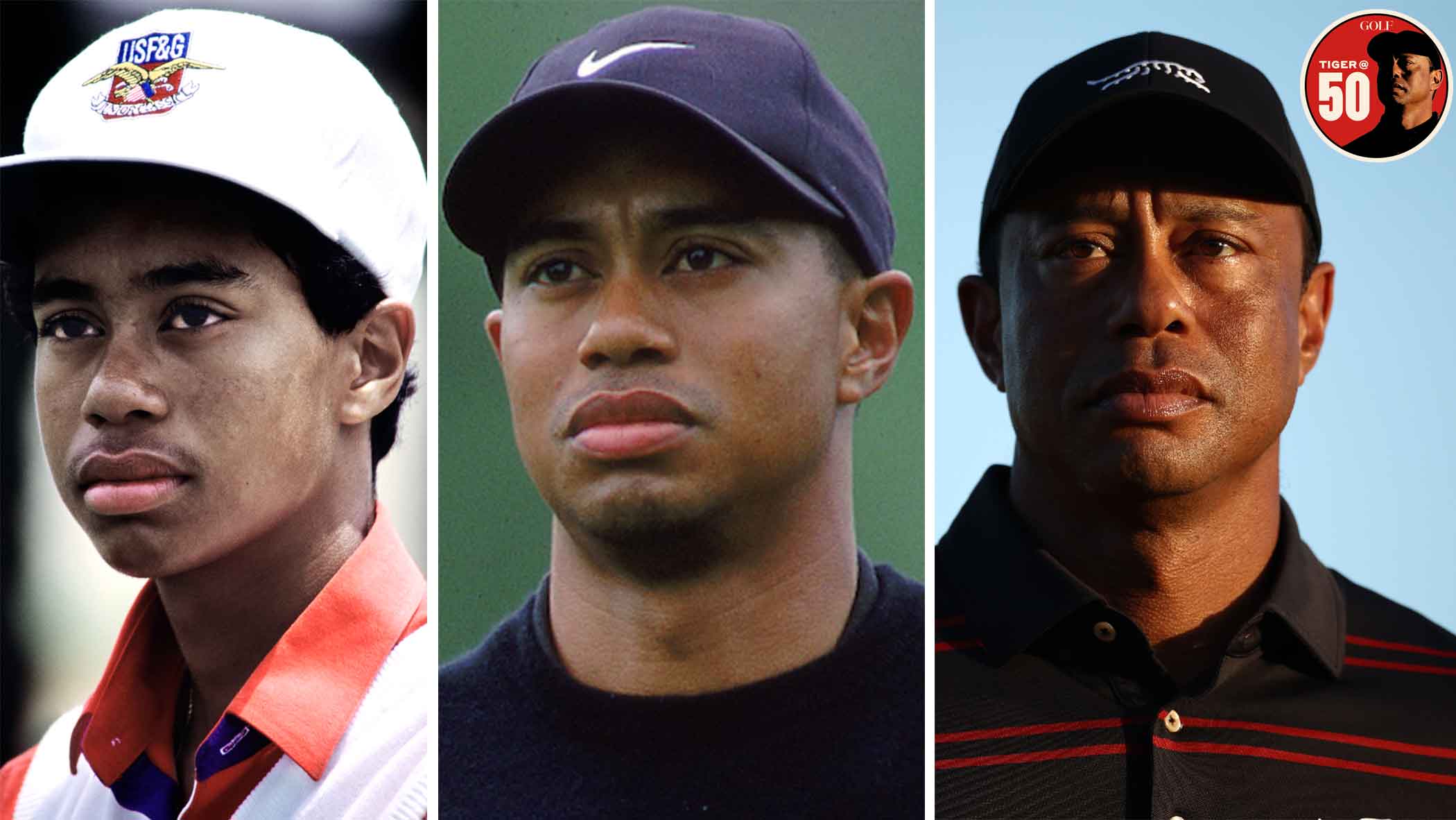

With his father as his coach, Dakota developed a fluid swing, with metronomic tempo. He began competing in the PGA Jr. League, which allowed him leeway to use a cart. His daily routine became a study in stark contrasts: from chemo to the golf course and back again. Last summer, his PGA Jr. League team made an underdog run and came away with the state title, with Dakota playing a starring role.

Dakota also joined his local middle school team, a standout on the squad even as his chemotherapy continued. This past fall, on the morning of the final tournament of the season, Steve found Dakota upstairs on his hands and knees. He was throwing up.

“He takes a shower,” Steve says, “and throws up again.”

It was a cold, windy day, but there wasn’t any doubt. Dakota was intent on playing. On the range, he smoked his first shot, turned to his dad and smiled.

Then he went out and shot 69.

The second-place finisher was nine shots back.

Trying experiences lend perspective. In Dakota’s case, they have helped him handle pressure. Maybe you remember this indelible moment from a charity event at the 2019 WGC-FedEx St. Jude Invitational, where Dakota partnered with Justin Rose to raise funds for St. Jude. When Rose came up short on a 50-foot putt, Dakota was left with a five-foot knee-knocker for all the marbles. A large crowd watching, and $50,000 was on the line.

“I kinda just zoned in,” Dakota says. And poured it in the heart.

That same week, in a different setting, Dakota met two of his other favorite players, Justin Thomas and Jordan Spieth, when the pair dropped by the hospital to meet some of the patients. During their appearance, Steve busted out his phone and showed Thomas a video of Dakota’s swing.

“I was expecting him to hit the play button and just hand it back,” Steve says.

Instead, Thomas scrolled through the footage frame-by-frame, so impressed by what he saw that he waved Spieth over to have a look as well. There they stood, two of Dakota’s heroes, oohing and aahing over his swing.

“You want to talk about an unbelievable feeling (for Dakota),” Steve says. “It was pure excitement.”

In January of this year, Dakota had his final chemotherapy treatment, entering remission. He’s been out on the golf course, practicing or playing, almost daily since.

On April 2, when he reached the 16th hole, a warm breeze was working against him. The shot was slightly downhill, playing the yardage, making 7-iron the perfect club.

From his vantage on the tee, Dakota couldn’t see his ball land just beyond the bunker. But there it was as he approached the green, nesting in a cup that was filled partway with foam strips as a safety precaution.

He was playing alone, so the first thing he did was call his father.

“He said, ‘Daddy, you’re not going to believe this,’” Steve says. “I’m like, ‘What happened?’ And the excitement, you could just hear it in his voice.”

Shortly after he began his treatment, Dakota made a wish. His dream was to travel with his family to Spain to watch a professional soccer match. But dreams, like diagnoses, aren’t etched in stone, and Dakota has since updated his fantasy. His new wish, he says, is to fly to Scotland next summer and meet Rory McIlroy at the 2021 Open Championship at St. Andrews.

That doesn’t sound far-fetched.

Besides, would you ever put anything past this kid?

To receive GOLF’s all-new newsletters, subscribe for free here.

ADVERTISEMENT