Ed. note: The following essay was written by Laz Versalles, a former club professional in Minneapolis who now works in the healthcare industry in California. Versalles addresses some uncomfortable realities about what it’s like to be a golfer of color in America but also offers thoughtful action points the game can and should consider as it strides to become more inclusive.

****

“Can I help you” says the voice from behind the counter in the pro shop. It wasn’t a question, more of a warning that says, I see you, and you don’t look like you belong here. That’s how I am greeted one muggy morning at one of the top clubs in Florida.

“I’m fine, thanks,” I reply.

“Who are you here with.” Again, not a question, and the tone is unwelcoming to the point of being terse.

Sadly, this exchange is familiar, and at times, expected. The next step in this uncomfortable dance is the employees in the golf shop stays close to you, keeping an eye on your every move. They’ll find a stack of shirts to fold next to you, or a display to organize in whichever corner of the pro shop you visit. It doesn’t matter if you’re wearing a pair of $300 golf shoes or a $10,000 watch, all that matters is that your skin is dark and therefore you are black. And, to paraphrase Ta-Nehisi Coates, being black in America means you are always on parole, whether you like it or not.

In 2018, I was playing in the Southern California Mid-Amateur. As I was hitting balls just before my opening round, an employee of the club told me I had to get off the range since “caddies aren’t allowed to hit balls.” Imagine having to produce papers before a championship to an overzealous range attendant. Misunderstanding? Microaggression? Who’s to say.

This treatment isn’t a product of the game of golf, it is a product of American society writ large. If the history of your people in the Americas involves being enslaved, oppressed, mistreated, devalued, denied and minimized based solely on your skin color, there will almost certainly be some friction in every corner of your life. I do not blame golf for the racially-fueled discomfort I occasionally experience at clubs. I blame slavery and the hangover it gave American society that we still suffer from to this day.

And so here we find ourselves in 2020 in the throes of one of the most important moments of this American century. As a country we face profound questions about how we treat each other and what justice truly means in the land of the free and the home of the brave. In recent weeks, there has been discussion in the golf industry contemplating a different, but related, set of questions: How does our game approach equality? What do we make of golf’s exclusionary past and present? And finally, what can we do to bring more people of color to the game? To that last question, allow me to answer: We’ve been here. This game is ours, too.

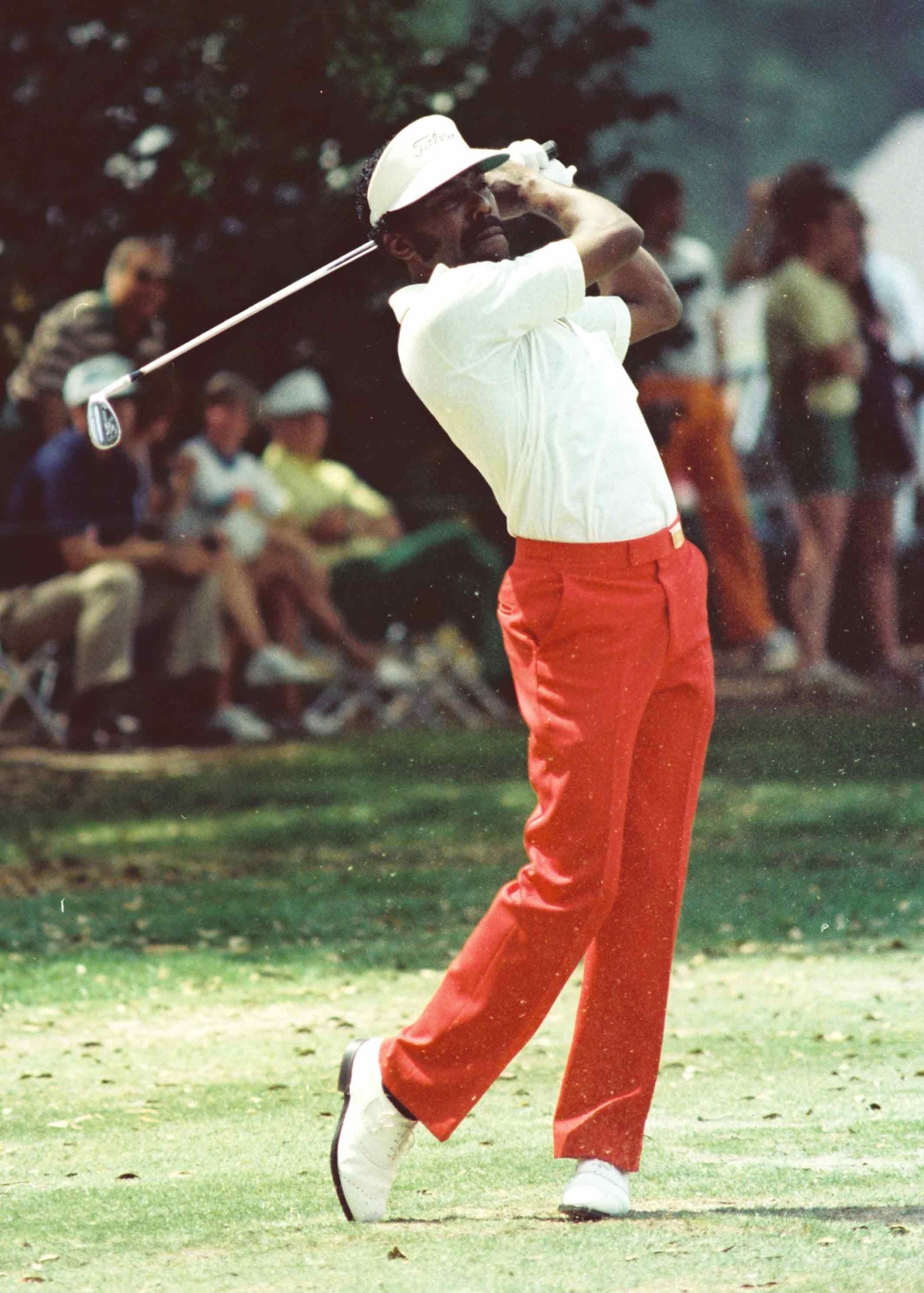

This may come as a surprise to Americans who think black golf started with Tiger Woods, but we’ve been here. The history of black golf is deeper than Calvin Peete, Charlie Sifford, Ted Rhodes and Lee Elder. It goes all the way back to the 1896 U.S. Open when John Shippen became the first black man to play in the national championship (he tied for fifth). The history continued with George Franklin Grant who invented the golf tee in 1899. So when I tell you we’ve been here, I mean, we’ve been here.

I grew up in one of America’s great golf cities, Minneapolis. The city where a police officer took George Floyd’s life. The city that rose up and screamed Black Lives Matter so loudly that the rest of the world joined in solidarity. That’s my hometown.

As the first-generation son of an Afro-Latino family from Cuba, I had to straddle the two worlds of being raised in a Spanish-speaking home in a largely white working-class suburban setting. My father was a fairly popular figure about town who played a little golf and liked a lot of action. If I was lucky he’d let me tag along to the golf course. Riding in the back of those gas-powered carts, choking on the fumes, was the greatest education of my life.

Just as my childhood had two worlds, so did the Minneapolis golf scene. If the game was at city courses like Hiawatha, Gross or Theodore Wirth I knew it was going to be with my dad’s Black friends. If we went to the suburban courses like Dwan and Rich Acres I knew it would be with his white friends. Once again I found myself navigating two worlds, the city games and the suburban games, each with different languages and social mores. It’s like the difference between a pick up game at the Jewish Community Center on the Upper West Side and going to Harlem to play at Rucker. Same game, but different. The city games were loose, loud, filled with trash talk and so much action that the final scorecard looked like Egyptian hieroglyphics. The suburban games were a bit more calm, but lively, cursing was far more prevalent, and the bets were always settled in a much more hushed tone in the clubhouse. These are the worlds in which a 9-year-old boy learned to play golf and understand the nuances of the game. I share these memories to illuminate a simple fact that not many people know: Like Minneapolis, just about every major American city has a rich African-American golf history. Like I said, we’ve been here.

Consider Langston Golf Club in Washington, D.C., where in 1939 a black man named Clyde Martin served as the club’s first golf professional. Washington D.C. is also the home of the first black women’s golf association, The Wake-Robin Club, led by Helen Webb Harris. In Minneapolis, Jimmy Slemmons was the godfather of black golf when in 1939 he started the Bronze Open, a showcase tournament for prominent Black golfers in the midwest. In Houston, Charles Washington launched the Negro Open Golf Tournament in 1952. When you think of African-American golf in Detroit, the first name that comes to mind should be Joe Louis, who loved the Donald Ross classic Rackham Golf Club which today is run by Karen Peak. These geographical meanderings lead us back to one point: we’ve been here.

Today, 23 years after Tiger’s historic win at the 1997 Masters, we see Harold Varner, III Cameron Champ and Tiger Woods as the most prominent black faces in men’s professional golf. But wasn’t Tiger’s dominance supposed to open the floodgates for black golfers? Aren’t organizations like The First Tee and the grow-the-game initiatives of the PGA of America bringing people to the course who would otherwise not have access? Yes, they are. And, no, they are not.

Why isn’t the golf landscape different? Why isn’t it darker? Despite all of the glory and inspiration Tiger has provided and all of the platitudes and praise we give to the well-meaning and deserving nonprofits, African-Americans still only make up around 5% of the nation’s golfers and a tiny fraction of the high-level amateurs and professionals. It would be short-sighted to look at these participation levels and believe that Tiger’s impact and the work of the nonprofits have failed to yield any fruit. The burden to maintain the Tiger Bubble post-Tiger will soon challenge all of golf, not just African-American participation.

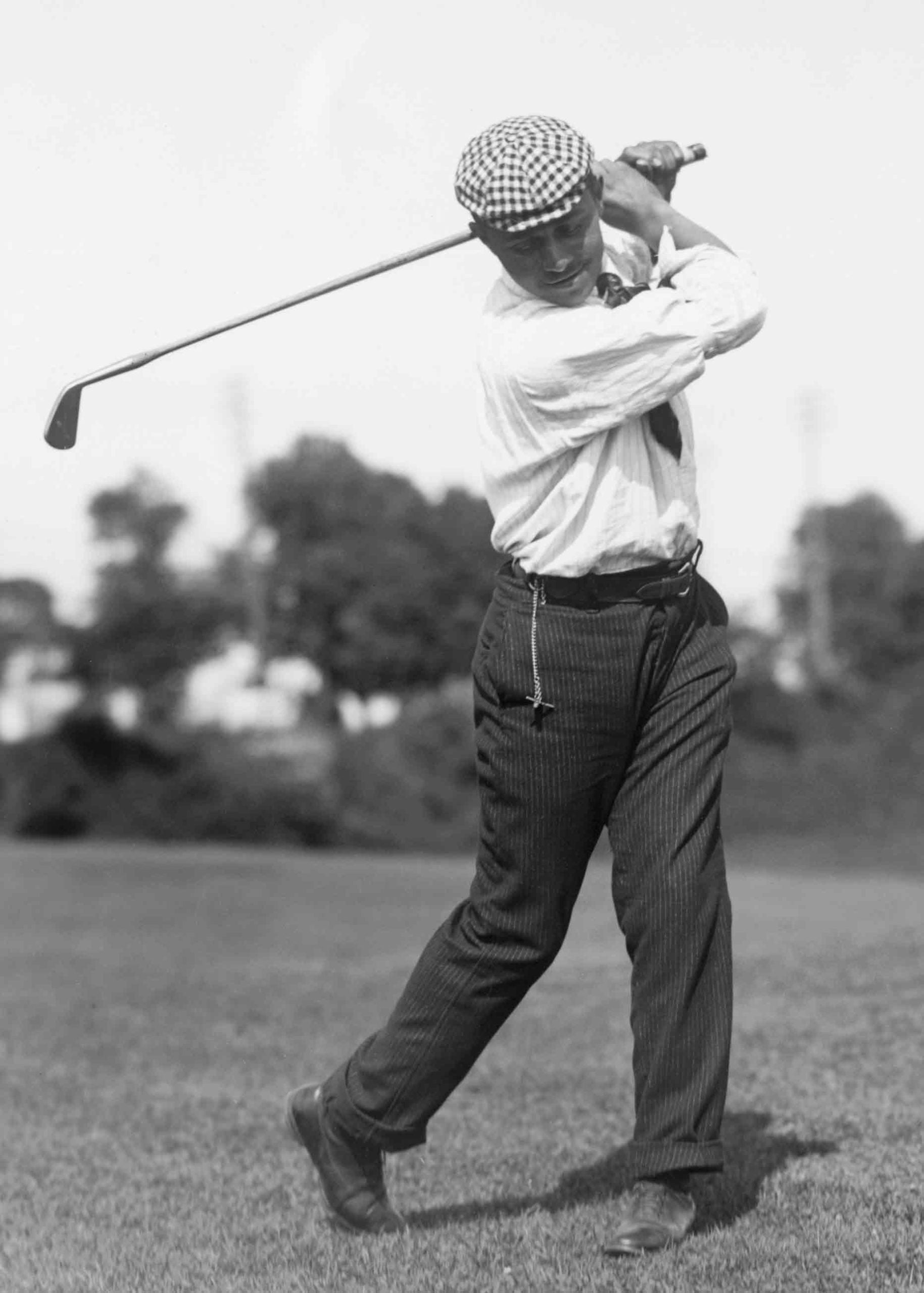

One could make a strong case that the root cause of the great migration away from the game by black golfers lies mostly with the golf cart. After all, it was the golf cart that killed the caddy yard, and the caddy yard gave life to African-American golf for decades. John Shippen, Charlie Sifford, Pete Brown, Lee Elder, Jim Dent and almost any other black player you can think of started as caddies. The same goes for a few poor white kids named Gene Sarazen and Ben Hogan, too. They were young, hungry capitalists who just happened to fall in love with golf while helping make ends meet at home. Those days are long gone and it does not appear we are headed back.

The primary reason is that the revenue generated by the golf cart is simply too great for many clubs to forgo. Again, capitalism. We need the stewards of the game recognize the carnage the golf cart has had on golf in the black community and step forward with a plan to do something about it. I believe every municipal course and daily-fee should have a caddie program, where the clientele pays a nominal fee to young, aspiring golfers who serve as caddies. How about $40 or $50 a loop, with the course offering a reduced greens fee to every golfer who takes a caddie? That’s a good wage for a teenager. Pace of play would improve, as would the scores of the golfers who learn a few things about course management and club selection. It would bring more kids to the game, especially those of color.

In light of the events that are transforming the racial and social narrative in our country today, PGA Tour commissioner Jay Monahan recently sat down with Harold Varner III for what was widely billed as a “thoughtful” 16-minute discussion on the state of golf’s race relations. Varner had already put it into words with a sincere and touching statement about George Floyd in an Instagram post that brought tears to my eyes. As I watch the video, I hear Monahan talk about The First Tee and Varner discuss his vision of having black kids play in the elite junior American Junior Golf Association event he’s involved with. In other words, they talked a lot but said little of substance. It’s been 30 years since Shoal Creek and golf is still talking about race but offering few solutions. I wondered how much more powerful that video would have been with someone like 81-year-old Jim Dent, who grew up in the segregated South, lived through the Civil Rights movement and still managed to build a successful career on the PGA Tour, despite the obstacles put before him by society.

So, where do we go from here? If you’re a member of a private club and you think the answer is recruiting a few more people of color, I would point to the words of Malcolm Gladwell who, in reference to Sammy Davis Jr., said, “The token succeeds at the cost of his own dignity.” Adding a handful of well-off black members to your private club’s roster is disingenuous, reflexive and far too micro. Most clubs did that after Shoal Creek and little else changed. But if these same clubs were to build grassroots caddy programs focusing on nearby low-income nearby neighborhoods? Now you’re talking. That’s impactful. That’s helping a family budget. That’s nurturing mentorships and relationships. That’s bonding.

From my perspective we need to move the narrative away from “how do we get more people access to the game” to “how do we get black communities more invested in the game.” A small idea for the PGA Tour: support the facilities that are on life support. When the PGA Tour is at Detroit Golf Club for the Rocket Mortgage Classic, will they look five miles down the road to Rackham Golf Club for events or perhaps a more affordable pro-am option? That’s an easy step. A bigger idea: many municipal golf courses are operated by large corporate lessors who can produce the capital to promise improvements that are often the deciding factor in a bid process. Let’s get the PGA of America or PGA Tour to be part of the solution to help people of color who are already familiar with the golf courses and the communities they serve to compete in the bidding process with much stronger footing underneath them.

Instead of asking what the PGA Tour can do to diversify those with access to the game, it’s time that Commissioner Monahan and others consider what they can do to diversify the pool of stakeholders in the game. Jay-Z didn’t call his 2001 album “The Blueprint” for nothing: “Pay us like you owe us for all the years that you hoed us / We can talk, but money talks, so talk mo’ bucks.” Consider it a Tiger Tax.

In his famous “The Ballot or the Bullet” speech of 1964 Malcolm X said, “We didn’t land on Plymouth Rock, the rock was landed on us.” The suffocating imagery in Malcolm’s words ring timely as our streets fill with protests of “I can’t breathe” and tens of thousands of Americans, disproportionately people of color, die of a virus that literally takes the breath from our lungs.

Now more than ever we need to come together and roll that big rock off our chests to empower people of color in communities of color, including African-American golf. Because, as I’ve stated time and again, we’ve been here. It’s time we started having some tough conversations so we can all begin to breathe freely. Together.

Editor’s Picks

How one man is using golf to fend off Parkinson’s disease (and helping others do the same)

This dream team of golf course architects is tackling D.C.’s munis (for free!)

How risky is golf during the coronavirus compared to other activities?