This is the final installment in a five-part Bamberger Briefly series about the TaylorMade Driving Relief charity event, to be played on Sunday afternoon at Seminole Golf Club, a landmark Donald Ross course in South Florida. You may read part 1 here, part 2 here, part 3 here and part 4 here.

I hope this won’t sound like bragging: I’ve played Seminole dozens of times over the past 30 years. I consider myself (in spirit, not in fact) a public-course golfer. In American golf, we have created an unhelpful public-private divide in our own image. You don’t see that in the motherland. Throughout GB&I, you can go on the website of almost every private club and just sign up to play as a visitor. The doors are heavy, but well-oiled. Still, to be truthful, the very things I protest here — elitism, separatism — are central to the thrill of being at Seminole. Yes, there’s a lot of hypocrisy here. What can I say? It’s in our American spirit. We are an aspirational people.

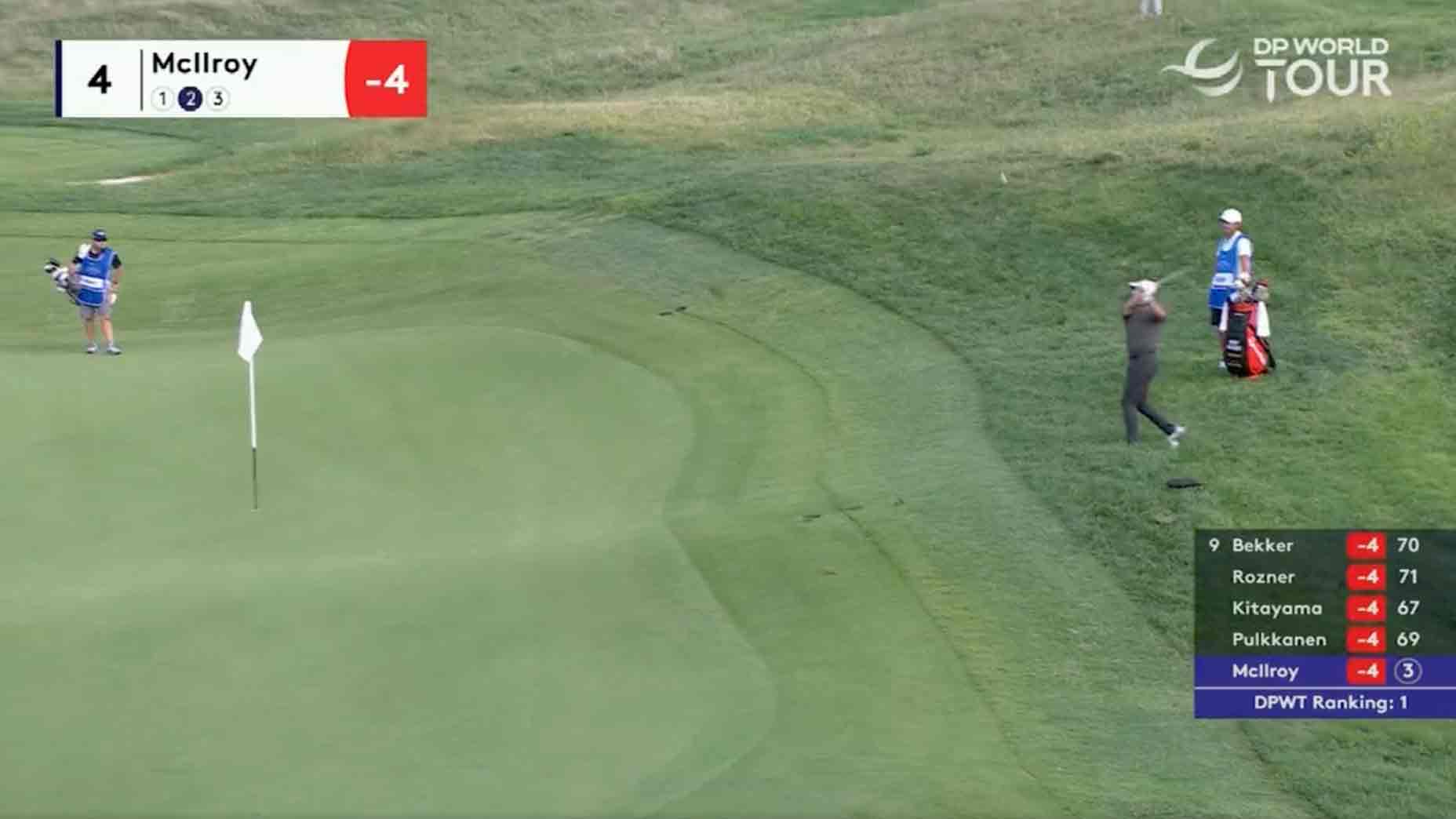

On Sunday, the doors to Seminole will open, at least on TV. Rory McIlroy and Dustin Johnson will play Rickie Fowler and Matthew Wolff and the curtains will be pulled back for an afternoon and millions of us will get a glimpse of the place for the first time. Very cool. But it won’t be like being there.

Here’s being there: You’re a guest, sitting down for lunch with a member. Suddenly, an older gent — a member, of course — casually joins you. It’s not planned. Of course not. The man is famous, in a limited sort of way. It’s Billy Joe Patton, the amateur golfer who finished a shot out of the Snead-Hogan playoff in the 1954 Masters.

Now where else is that going to happen except at Seminole and a few places like it?

That was in 1999, during the Florida Swing. Steve Elkington won Doral that year, Vijay Singh won Honda, Tim Herron won Bay Hill and David Duval won the Players Championship. I was at three of the events, but what I remember best about that March is the half-hour with Mr. Patton. I’ve been harsh about the Players over the years, and the course (TPC Sawgrass) and the newish Taj Mahal clubhouse that abuts it, and those days are over. For starters, a half-day at Sawgrass and a half-day at Seminole are about the same thing, if you wish to look at it that way. Warm up, play the course, have lunch. You’re living the dream if you’re doing either.

The differences are so subtle as to be meaningless, but you could summarize them thusly: Seminole has no marketing department. It all seems to just happen there. Now of course that’s not true, but it seems true. It’s like George Clooney’s life, from a distance — or maybe the life and times of Fred Couples is a better example. We’re drawn to magic, to ease. Old Billy Joe Patton — he was 77 then and as modest as could be — just sat himself down and ordered a sandwich with Tarheel drawl. It was lunchtime.

I’m drawn to older people. I like to collect their stories and try to learn something along the way. Golf is a good place for that hobby, and Seminole is an especially good place to practice it. My first host there was a Boston Brahmin named Ted Emerson. A gent, and he knew Francis Ouimet well. I knew Ted Emerson well. (That’s golf for you. I spent about only 10 days with Ted Emerson, but I feel like I can say I knew him well.)

All these years later, I can also say I shook the hand of the man who shook the hand of Francis Ouimet. For you young people or for anybody who doesn’t have Golf Channel: Francis Ouimet won the 1913 U.S. Open, in a playoff against the two most famous touring pros in the world in that era, Harry Vardon and Ted Ray. Ouimet set the stage for Billy Joe Patton, with Hogan and Snead in the Vardon and Ray roles.

Some of you will know the name Bill Campbell, a World Golf Hall of Fame member, a lifelong amateur from Huntington, W.Va. He knew Sam Snead, Ben Hogan, Billy Joe Patton, Jack Nicklaus. Bob Jones, Cliff Roberts, yada yada. Everybody. Campbell, a longtime Seminole member, was notably forthright, and his exactitude was both impressive and grating. He once wrote a long piece for Sports Illustrated about his life in golf and insisted that when golf was played in a threesome, it was still a pairing, even though pairing implies two and violated the SI stylebook. I had the feeling Campbell would have walked away on that one word alone. In the end, his threesome was a pairing.

Bill was a careful, frugal insurance man with a wife and six children and two expensive hobbies, golf and flying. He started playing Seminole in the early 1950s and when he was invited to join the club, in the late 1960s, he told me he really couldn’t afford to join. But he was so drawn to the club — and to the aura of Hogan, one of his heroes, that permeated it — that he couldn’t say no. He had played golf at Seminole with Hogan, and Hogan didn’t play with that many people.

Campbell’s children were not interested in golf. Still, one day he put them all in the family station wagon and told them they were going to Seminole to watch Hogan practice. His instructions were clear:

“Don’t ask him anything. Just watch. You don’t have to have a good time. Just remember it.”

That story tells you something about Bill Campbell and his exemplary parenting method. It of course tells you something about Hogan and Seminole, because Hogan could have done his winter practicing anywhere and chose to do it there. It’s astounding to think about Bill Campbell joining Seminole even though he knew it was imprudent to do so. In other words, the depth of the attraction. The girl or guy you shouldn’t date but do anyway.

But what a scene, for us, all these years later: six kids, standing on a range, watching an old man smoke cigarettes and hit golf balls, a pink clubhouse behind them, the yawning Atlantic over a nearby dune.

Michael Bamberger welcomes your comments at Michael_Bamberger@GOLF.com.