AUGUSTA, Ga. — In 1953, George S. May did something radical: He put his golf tournament on national television.

May was the owner of Tam O’Shanter Country Club, just outside Chicago, and he’d been lavishly spending to put on “The World Championship of Golf” for several years. The tournament’s purse dwarfed the rest of the Tour schedule, so May attracted plenty of big names — Ben Hogan, Sam Snead and Julius Boros are among the event’s winners — and plenty of attention, too.

May decided the time was right to take the event’s exposure to the next level. In 1952, when most Tour stops were paying the winner $3,500, May upped the Tam O’Shanter winner’s share to $25,000. He made an even bigger move the following year, when he elected to pay ABC to show an hour of coverage per day. That’s right: The host of a top golf tournament actually paid someone to put it on the air. This would be the equivalent of Jack Nicklaus paying CBS to air the Memorial Tournament. In 2020, that arrangement works the other way around.

Golf had appeared on television before, first at the 1947 U.S. Open, which was broadcast to local St. Louis audiences. But the 1953 World Championship of Golf became the United States’ first nationally-televised golf tournament.

May couldn’t have picked a better year to launch. Two million viewers tuned into the final-round broadcast, and the event ended with unimaginable excitement: Lew Worsham came to the 18th trailing by one shot and holed out from 104 yards for eagle and a walk-off win.

The first-ever nationally-televised U.S. golf tournament was the World Championship of Golf at Tam O'Shanter in 1953.

— Dylan Dethier (@dylan_dethier) November 17, 2020

It may have also been the best finish ever: Lew Worsham came to the 18th trailing by one shot and holed out from 104 yards for eagle and a walk-off win. pic.twitter.com/ET5Kejlakj

The spectacular finish would prove difficult to replicate (how do you top a walk-off eagle?) but the concept was sound: There was a demand for golf viewing that extended far beyond a host site’s members and friends.

Golf’s television broadcasts grew in the years that followed. More cameras. More golf shots. More sophisticated, more comprehensive, more expensive, more expansive. But the fundamental goal remained the same: Cover the drama of this live sporting event as it happens.

The first Masters TV broadcast came a few years later after that first event at Tam O’Shanter. The powers-that-be at Augusta decided to sell the tournament’s rights, which were worth a pretty penny. But they didn’t want a big check. They wanted control. They wanted the ability to showcase the best possible version of Augusta National and its invitational tournament. In 1956, six cameras captured the action from the final four holes as Jackie Burke, Jr. took home the green jacket.

The first Masters broadcast in color came a decade later, in 1966, when CBS put a spectacular, vivid golf course on display, giving the public their first full view of the resplendent property we’re now conditioned to expect every April. Green expanses. Music. Flowers. Birdsong. Augusta National was well on its way to becoming much more than a golf course. It was an idea.

In some ways, CBS’s Masters coverage was one-of-a-kind. The network continued to innovate in the years that followed: helicopter flyovers, to-scale course models in studio, Dave Loggins’ now-iconic theme music. Augusta National worked with its broadcast partner to show off Augusta as the world’s most perfect course, a field of golf holes with no equal.

More than any other tournament host, Augusta National’s leadership valued mystique, too, and didn’t want to dilute its product. For decades, the broadcast provided viewers with limited course access, showing only the back nine until 1995. What was the rest of Augusta National like, tournament week or any other time of year? Myth and speculation filled in the gaps. The tournament hosts liked that.

Over time, the demand for more coverage became apparent. More cameras brought us more holes, more shots, more backdrops. In 2005, the proliferation of crystal-clear HDTV meant Augusta would get its close-up. With each increase in exposure, the pressure ramped up to make Augusta’s reality match the product (visual flawlessness) that CBS had been broadcasting for decades. The internet came to Augusta, and streaming opened new doors: Featured groups and featured holes put more competitors on camera.

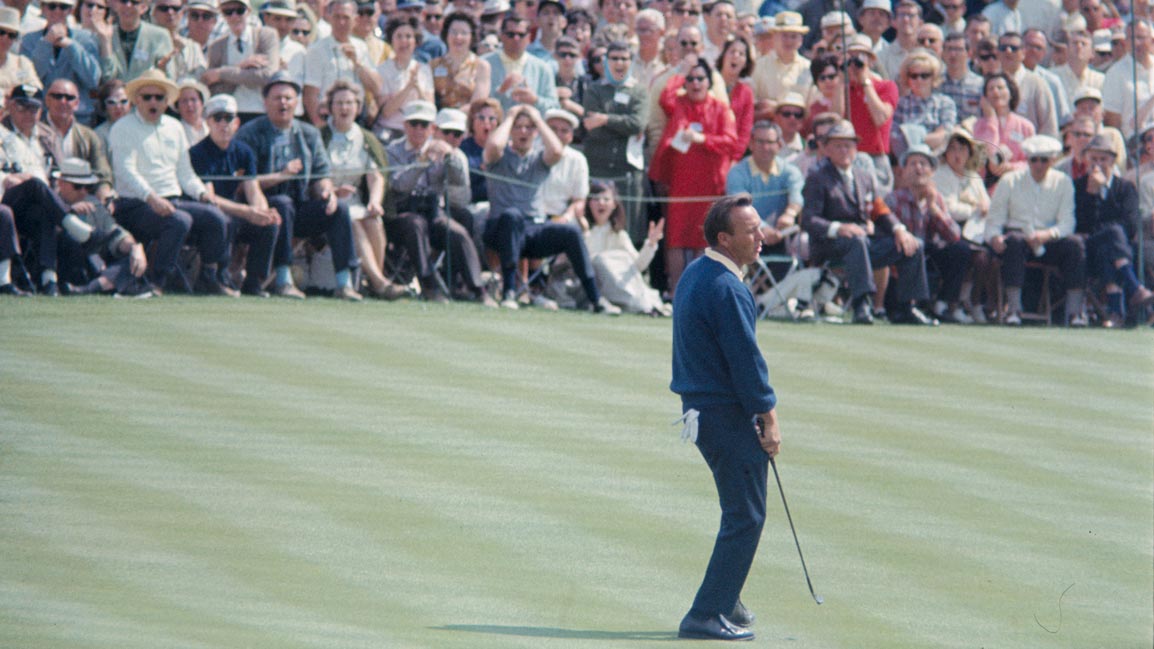

Even though the Masters was a one-of-a-kind broadcast, the fundamental goal remained the same: To cover the live sporting event as it happened. The tournament, like most sporting events in the 20th century, was being staged for the in-person audience. The cameras and microphones were there to capture the roars. The commentators were there to relay the atmosphere. The whole premise of the broadcast being exciting for viewers at home was that it was exciting for viewers on site.

Until this year.

It would be overly simplistic to suggest that 2020 was the year that live sports flipped from in-person events to television products. TV is king — that’s nothing new. Early-round March Madness games often play in front of empty gyms and massive TV audiences. On weeknights in the fall, sparsely-attended MAC football games take over ESPN. Plenty of golf events don’t sell out, either, but the hard-to-get-to Hero World Challenge still rates well on television and the Tiger-Phil Match had a tiny in-person audience, and heck, rights to live PGA Tour golf just sold for $680 million. If making TV the priority means the tail is wagging the dog, well, that tail has been wagging a while.

But this summer, as each major sport figured out creative ways to restart its season, an essential question hung over the entire process: Can you even have sports without fans there to watch them? When golfers teed off at the fan-free Charles Schwab Challenge in June, the immediate answer was yes. Golf was less affected than many sports; there are no courtside seats, there’s very little booing and, with the exception of the 2018 Tour Championship, nobody ever rushes the field. The early events back were a godsend. Ratings were way up year over year, reflecting Americans’ collective desire for live sports.

But there’s no question the year’s biggest events were missing a little something. When Justin Thomas and Collin Morikawa traded mind-bending pressure putts at Muirfield Village, we rued the lack of celebratory cheers. When Dustin Johnson and Jon Rahm traded blows at the BMW Championship, we wished a crowd was there to elevate the experience. The players themselves admitted that the year’s first two majors felt rather non-major, despite an historic municipal venue for Morikawa’s coming-out party at the PGA Championship and the grand stage of Winged Foot for Bryson DeChambeau’s ground-shaking victory.

Exclusive photos from Augusta National: The 20 best Masters photos you haven’t seenBy: Zephyr Melton

“All these tournaments are created by their atmosphere and everyone has a different feel, and every tournament since coming back off the lockdown has felt the same,” Rory McIlroy admitted mid-summer.

Golf’s true fan-free litmus test would come at the Masters. In the golf world, it’s how we keep track of time. The entire sports world tunes in and takes stock of the game vis-a-vis its top competitors and green-jacket winner. The success of the Masters can serve as proxy for the success of the sport. So much of the lore of the tournament comes from the roars of the crowds, echoing through Augusta’s corridors of pines. Without those fans there to watch, what was the vibe?

For media members, the experience was fundamentally different. The media typically cover the atmosphere. This year, they were the atmosphere.

“The marquee groups over the first couple of days, they had some members with them, members of the media, and so there’s a little bit of an atmosphere out there,” McIlroy said. “It’s not much, but it’s better than nothing.”

As you saw on your television screens, the course was far from empty. Masked members and guests tracked the tournament’s high-powered groups, with several hundred following Dustin Johnson’s group on Saturday and Sunday. But neither reporters nor members were likely to cause a ruckus — that’s typically left to the rabble-rousing patrons soaking in a bucket-list visit. Nay, the instinct for most of the green jackets is to play it cool, and play it cool they did. They were behind the scenes at the filming of a TV program. Quiet on the set! As a result, it was often hard to tell whether a shot was great, poor or in-between. It was eerily quiet.

Who are all the people at Augusta National watching the Masters?By: Dylan Dethier

At a typical event, players’ “teams” — their significant others and their coaches — watch them in silence, hoping for anonymity as they walk. This year, their cheers were loudest.

When Tony Finau holed out for eagle at No. 15 on Thursday, his wife Alayna’s scream echoed off the pines, drawing a grin from Finau.

On Friday, when Matt Wolff rolled in a terrifying birdie putt from the back fringe on 9, his coach George Gankas could be heard above the smattering of applause. “Wolff-ayyyy!”

And when the defending champion, Tiger Woods, approached the 18th green on Sunday afternoon, nobody clapped until his manager, Rob McNamara, decided to take matters into his own two hands.

Parts of the in-person viewing experience were phenomenal. You could see from hole to hole in ways that patrons and bleachers don’t usually allow. You could hear players and caddies talking through yardages, or lunches, or NFL gambling lines. You could take an evening stroll and check out one group and then another and then another, front-row seat each time, golf’s most iconic venue as a backdrop.

All the while, the Masters was busy providing an unprecedented level of access to its viewers at home. Every single shot was captured on video and posted to the leaderboard. Every single shot! ESPN and Golf Channel had full on-site presence, and Masters.com offered five live channels plus the ability to customize groups you wanted to watch — in all, a dizzying array of viewing options. Even better, the course was far more visible and understandable; the way the holes connect from one to the next translated better from life to screen.

It’s just that the atmosphere was rather less than status quo. Think about a scene from the tournament any other year: If Jordan Spieth makes a putt, he acknowledges the crowd. He doesn’t wave to the cameras or the people at home, even though he’s fully aware that he’s on camera. At this year’s Masters, Spieth generally didn’t wave at all.

This year’s edition maintained certain other traditions that were invented for spectators but carried on for television or tradition or force of habit. Every player was announced on the 1st tee, for example, even if there was nobody there to cheer them. Tiger Woods put the green jacket on Dustin Johnson outside, even though there was no ceremony to accompany the act. And players skipped balls across the 16th pond during practice rounds, even though there were no fans to request they do so. One such fan-free skip ironically led to the most-viewed moment of the week: one video of Jon Rahm making a skip-ace has some 27 million views on Twitter as of this posting.

What this all adds up to is a successful but wholly different Masters. It marks a complete and total reversal from the Sunday-back-nine-only school of thought. Access has been prioritized over mystique. This has two effects: The first is that viewers got a better look than ever at the majesty of Augusta National, which is, at its core, one of the most epic venues to take a walk or hit a ball. The second effect is that we get to see the seams a little bit more. Not everything is hunter-green all the time, especially in November. There’s some mud in the rough and some purple in the greens and some leaves on the tees. This is a net win, because the imperfections remind us it’s a real, nearly-flawless place.

Before the Masters was ever shown on television, golf fans would have to wait for the results when they got published in their morning paper the following day; only those who’d seen the action firsthand knew the result. That’s the most interesting reversal of all: The viewers at home are fully in the know, while the lucky few on the course are in the dark, limited by the coverage of two eyes, two ears, two feet and Augusta’s trademark no-phone policy.

For the first time ever, this Masters wasn’t put on for the people there to see it. The broadcast’s original fundamentals were to cover a tournament put on for the fans — but this was a tournament for television. For the internet. The tournament went off without a hitch, and brought joy and entertainment to millions of homes around the globe. It also represented a fundamental shift in the sport and the way we watch it. Whether that’s circumstantial and temporary or here to stay is yet to be determined.

But one aspect of the action at Augusta felt like a real throwback, all the way to 1953. Much like Tam O’Shanter’s original televised event, Masters competitors performed in front of the membership and a limited group of guests. A club and its members cheering on players — with cameras there to capture the action.

What’s old is new again. But what’s changed may never be the same.