Welcome to Play Smart, a game-improvement column that drops every Monday, Wednesday and Friday from Game Improvement Editor Luke Kerr-Dineen (who you can follow on Twitter right here).

I’ve seen it happen countless times. A golfer comes to an expert looking for more distance and somehow they conjure some up. An extra mile per hour of clubhead speed. An extra mile per hour of ball speed. Some specific tweaks could yield more distance without any additional speed. Somehow, the ball goes farther.

I’ve seen clubfitters do it. Teachers do it. Biomechanists do it. I’ve seen it happen with high handicappers and low handicappers. Juniors, collegiate and pro golfers. I’ve even seen it in my own game.

And it’s what I couldn’t stop thinking about when reading the findings in the USGA and R&A’s recent distance report, which was published Wednesday. It’s full of interesting stuff the USGA clearly worked hard on. At painstaking effort, they’re making clear they’re going about this issue methodically, with the best intentions in mind.

I want to be painfully transparent about this: I started relatively agnostic on the rollback debate, but have since found myself drawn to an anti-rollback position because it’s hard to see how any kind of rollback would actually have the desired effect. But like most reasonable golf analysts, I’m also open to having my mind changed. And after reading this document, I can’t help but think we’re even less in need of a rollback than that camp’s proponents would like you to believe.

1. There’s good news for the recreational game

If there’s one overarching theme in this document it’s that the governing bodies are drawing a firm distinction between professional golfers and recreational golfers. They’re actually quite unequivocal in saying that restricting distance is not an issue in the recreational game. They’re focused on the pro level, and any changes they would implement would not negatively impact the rest of us. In fact, they even flirt with the opposite idea: Wondering if any “adoption of these potential Model Local Rules could also allow the elimination of the MOI limit for recreational golfers.”

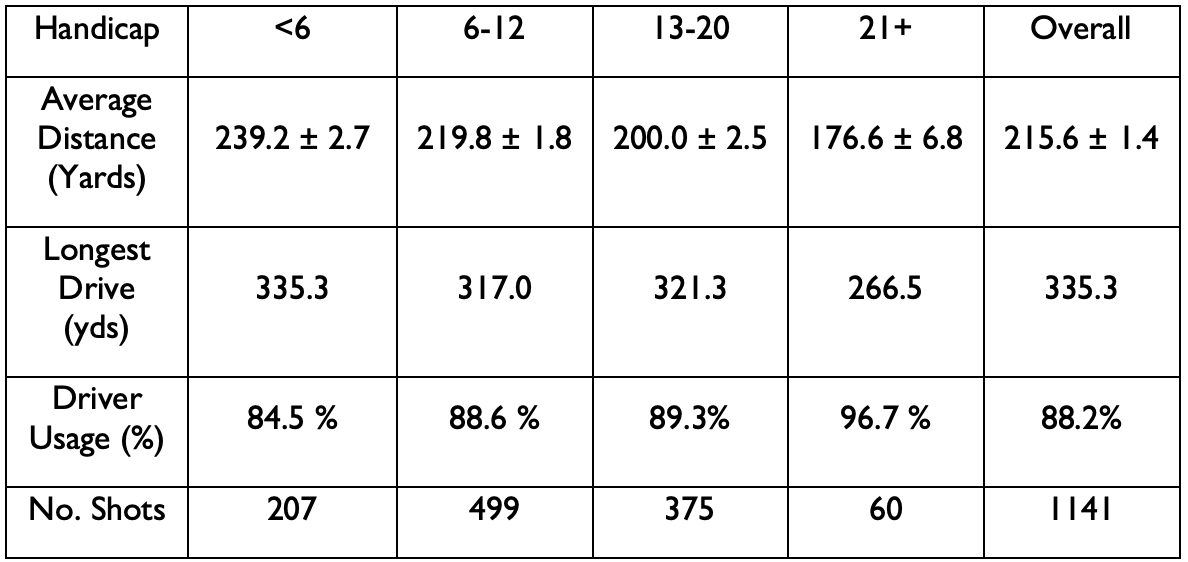

That, translated into layman’s terms, is the USGA wondering if they could write a rule that would actually make the kind of drivers recreational golfers use more forgiving, and easier to hit. That, after all, is why regular golfers don’t hit the ball farther: Because they’ll pump two drives 250 yards then top one 50 yards, for a cool 183 yard average. It suggests there could be a universe where the USGA greenlights drivers that are easier to hit for recreational golfers, and harder for pro golfers. You could imagine a world where that becomes a joyous cash grab for club manufacturers that leaves the rest of us hitting farther drives.

The USGA and The R&A have released updated areas of interest on hitting distance in golf.

The governing bodies are continuing their work to advance the game's long-term health.

Learn more: https://t.co/xKqTp6ZHm5 pic.twitter.com/KZJnsb85gq

— USGA (@USGA) March 16, 2022

Of course, what we’re describing in the process is bifurcation. A different set of rules for pros than the rest of us. That’s a change that shouldn’t be taken lightly, because it undercuts a core trait of this game that has stood for hundreds of years. It fractures a game that is fundamentally equal in the way it’s played, into two parts for no obvious reason.

It’s also worth noting how this could alter the overall viewing experience: Golf fans can appreciate a pro smashing a 320-yard drive because they have a frame of reference for it in their own games. They’re playing the same game you are, but they’re making it look easy. Will you be as impressed when some pro hits a 280-yard drive with restricted equipment when you can hit it that same distance with your own more forgiving gear? I’m not so sure.

2. Since 2003, the distance increase is probably smaller than you think

The entire reason we’re having this debate is because the established narrative is that distance has gone through the roof in recent years. Like most things, there’s an element of truth there but the reality is somewhat muddled.

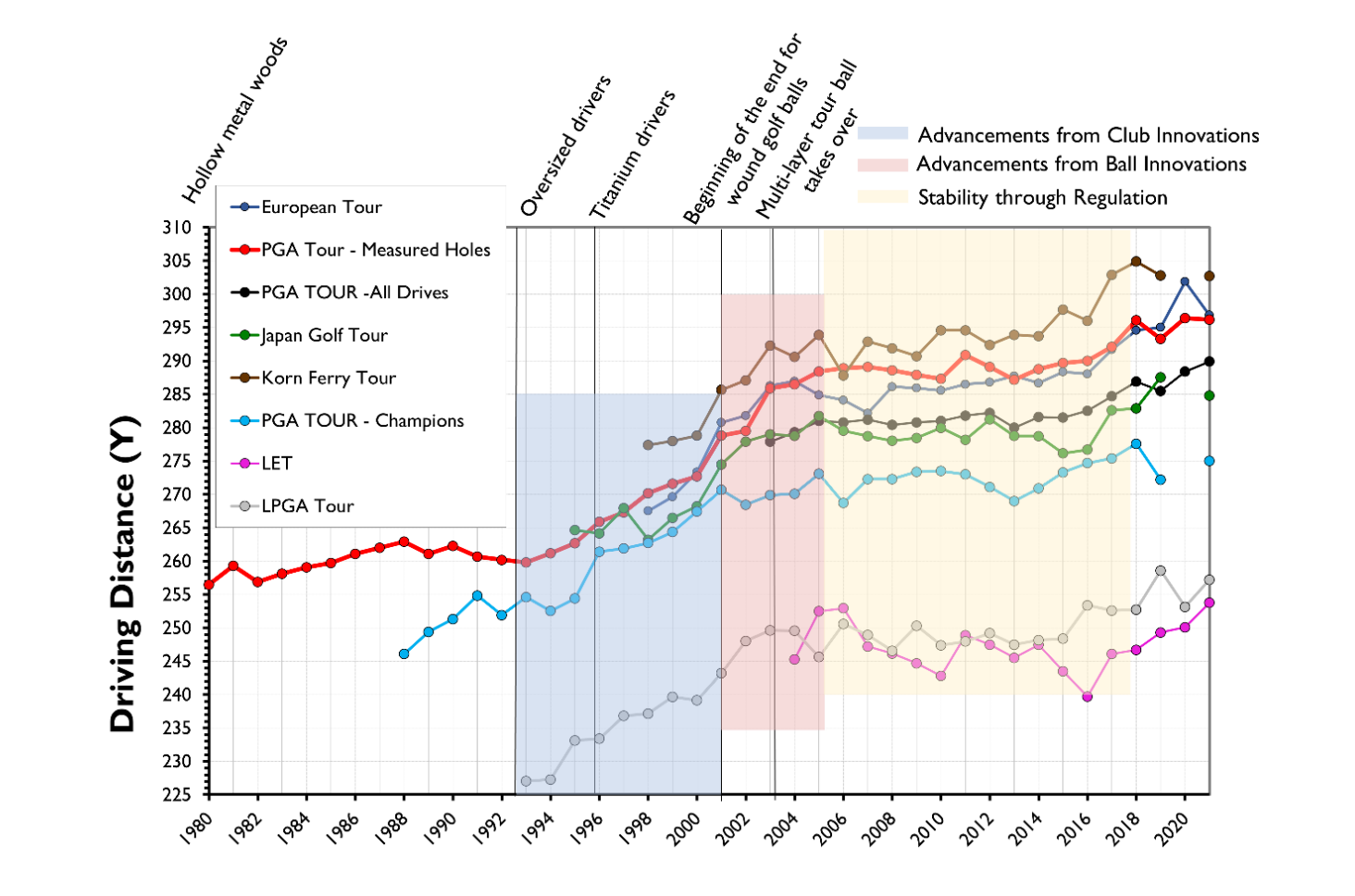

As the USGA and R&A outline in one area, the average driving distance did indeed increase steadily until 2003, due to a few obvious technological factors: Players transitioning away from wooden driver heads, titanium drivers getting larger, the golf ball getting more advanced. But since 2003, that distance increase has flattened. Distance gains were negligible between 2003 and about 2014, and has started increasing again in recent years. In all, in the nearly 20 years since 2003, we’ve seen an average increase across all pro tours of between 1.9 percent and 4.3 percent.

The damage has already been done, rollback champions say. But what’s interesting about the recent increase is that it occurred in the era the governing bodies call “stability through regulation,” which underlines the fact that recent gains are not primarily equipment-driven.

Instead, pros have been able to gain distance in the era of “stability” not because of any comparable persimmon-to-titanium technological breakthrough, but because the recent increase has coincided with the widescale adoption of Trackman-style technologies, more advanced data on the golf swing, innovative clubfitting processes, and a more scientific approach to training the body. Players’ training is simply more optimized than ever before. Just look at 48-year-old PGA Tour player Greg Chalmers or 48-year-old Stewart Cink. They gained swing speed not because of some endemic problem in their tools, but because they’re working harder and training smarter, fueled by more cutting-edge research.

That’s the nature of human progress: We get better at stuff as we go. We’re seeing it happen in real time in golf.

3. Players are more optimized for speed now

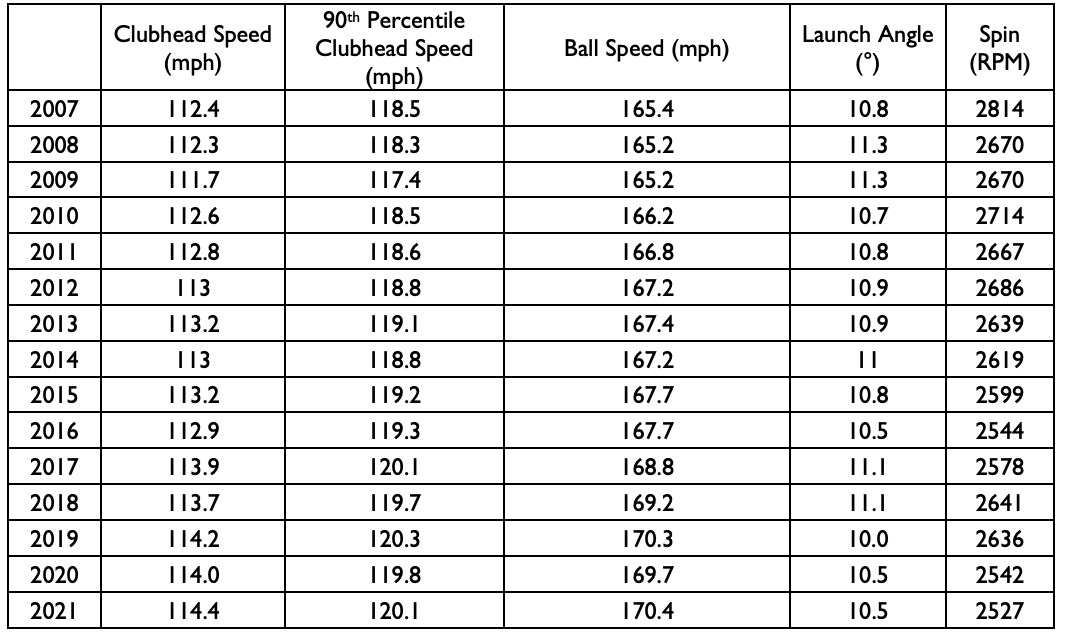

The proof is in the pudding when we look at some of the other data that the distance report highlights. Since 2007 we’ve seen a 2 mph increase in clubhead speed. Why? Because players are more intentionally chasing speed. They’re training more specifically, optimizing their swings for speed, and the sport is self-selecting elite athletes who can send it. The rise of Trackman and other similar technologies means more distance requires keeping an eye on your optimal launch conditions, which is why the spin rate has dropped about 300 rpms concurrently. More physical strength means more clubhead speed; different technique and smarter clubfitting means less backspin; the combination of those two things means more ballspeed and therefore, distance.

It’s why, in simplest terms, I remain skeptical that any form of bifurcated rollback solution for pros would be as much trouble as its worth.

It’s all too easy to think there’s a singular solution out there that will target one small slice of the pie without affecting the rest of it. Innovations in coaching, and training, and the science of how to create speed in the golf swing, will continue to advance. Analytics will continue underlining the inextricable role speed plays in overall success — which has been true in every era — and it will draw better athletes away from other sports because of it. That’s what we’re witnessing in golf today: The rise of smarter, stronger athletes at the tiniest, uppermost echelon of the game. To me, that’s something to be celebrated.