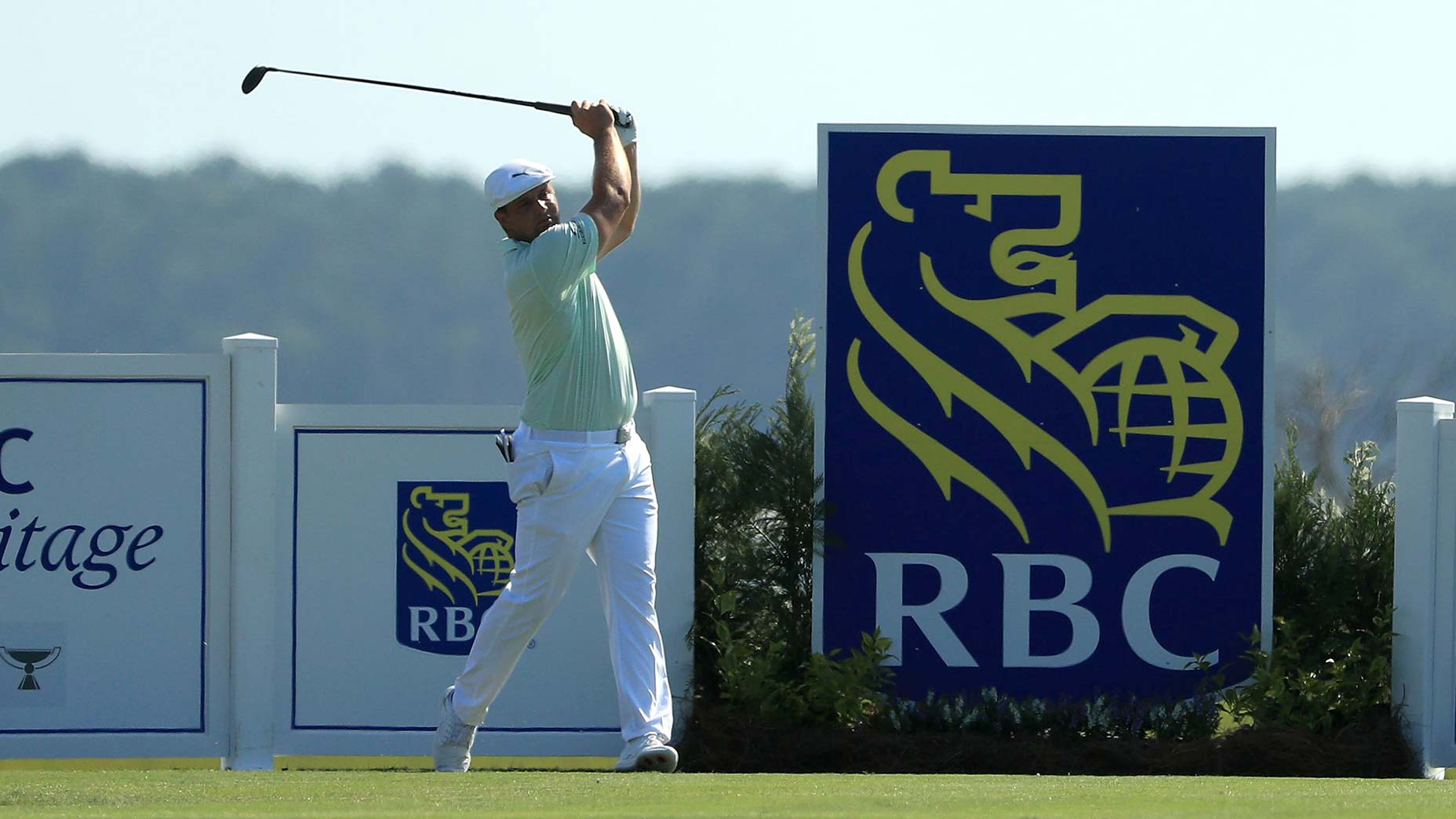

The biggest story of the the Tour’s return last weekend, both literally and figuratively, was Bryson Dechambeau. On nearly every tee box, commentators noted Bryson’s “bulk” or “size” before he launched a ball into orbit.

Though the awe over his prodigious drives was merited, our collective fixation on his size being the key factor may only have been half the story. The change in his physique was apparent, but the change in his technique should have drawn some attention as well.

This is not to say that Bryson’s training didn’t have a significant impact on the jump in driving distance. Bryson is clearly bigger and looks stronger than he was in 2018. Increasing strength can improve power and control in several key ways.

The stronger a golfer is, the more torque he can apply to his club which helps generate more speed in the downswing. In order to take advantage of that increased speed through impact, a golfer must counter the extreme centripetal forces he exerts on the golf club in the downswing.

In other words, a golfer must pull back on the club with their lead arm and body to keep the club rotating on a circle. This requires tremendous strength as the speed of the club increases. On average, a golfer must pull back with approximately 88 lbs of force to counterbalance a clubhead moving 100 mph. If you increase that clubhead speed to 150 mph, he would have to pull with approximately 196 lbs of force. That requires a big increase in the strength needed to stabilize that new clubhead speed. This is why most amateur golfers would buckle with their legs or early extend towards the ball if they tried to hold onto a club moving 150 mph.

While Bryson’s gains should be celebrated, we wanted to highlight the mechanical changes he and his coach Chris Como have made in his swing which are as responsible for his extra distance as anything he did in the gym.

Como is very comfortable incorporating technology to help communicate scientific principles in the swing, so it’s no wonder he and Bryson are a good match. Together, they have been able to make key adjustments in Bryson’s swing to take advantage of the additional horsepower his body now affords.

Here are a few of the more notable changes in Bryson’s move:

1. A Faster backswing

In this comparison of Bryson’s 2016 swing vs. 2020 swing, his backswing is obviously faster in the video on the right.

💪 @B_DeChambeau's bulked up.

— PGA TOUR (@PGATOUR) June 11, 2020

Driving distance in 2020: 321.3 yards

Driving distance in 2016: 294.6 yards pic.twitter.com/6lklSqOE2U

In an interview with GOLF.com’s Luke Kerr- Dineen, Dr. Sasho MacKenzie had this to say about the benefits of a faster backswing:

“Some coaches talk about the benefits of making a slow backswing, but that could be costing an athletic golfer speed. In reality, a faster backswing triggers greater muscle activation in transition, which can result in a faster downswing”

Think about how this principle would apply in an athletic activity like a vertical jump. If you’re trying to jump your highest, would you rather squat down slow or squat down fast? Go ahead, try it. Within reason, squatting down faster will give you a better opportunity to create a more explosive stretch shorten cycle, resulting in more force and a higher vertical jump.

Whether or not they heard it from Mackenzie, Bryson and Como have definitely benefited from implementing this in Bryson’s swing. When Bryson takes a faster backswing, it forces him to generate more torque, or force, with his hands to the grip of the club to change directions. This increase in force production can increase the ultimate clubhead speed.

2. More dynamic lower body

If you’ve followed our work, you’re probably familiar with the relationship between clubhead speed and ground reaction force. The more ground reaction force a golfer can create by pushing against the ground, the greater their potential clubhead speed. This is part of the reason why many of the longest hitters in golf are also some of the biggest jumpers.

How does this apply to Bryson? Bryson appears to make a more dynamic move with his lower body in the swing. If you slow down his backswing, you can see his lead heel lifting a few centimeters off the ground (Hi, Brandel!). In the downswing, he stomps the heel back against the ground to help rotate his pelvis and generate energy up the kinetic chain. Allowing the lead heel to lift not only helps create a few more inches of length in the backswing, but being able to stomp back against the ground also helps create greater ground reaction force, which can be converted into rotational speed.

You don’t need a force plate for evidence of this, either. Just look at where his lead foot starts vs. where it ends up. Bryson takes advantage of Newton’s Third Law by pushing against the ground so forcefully on the downswing that the ground “pushes back” and causes his foot to jump away from the target line.

The mechanical changes that Bryson has made don’t get the same attention as the change in his physique, but they are as responsible for the jump in speed as what he’s done with his body.

— TPI (@MyTPI) June 13, 2020

Beyond impressive to put this into competitive play like he has.

pic.twitter.com/2z2NnEX6ji

3. Swinging Harder

This might sound overly simple, but most pros can access much more speed than they are comfortable putting into play. When we practice power techniques with players at TPI, it’s not uncommon for them to see a clubhead speed increase of 6 – 8 mph in the practice session.

Tony Finau recently posted a great example of this. He plays tournament golf at ~180 mph ball speed, but touched 200 mph ball speed while messing around during a practice session with his coach Boyd Summerhays last fall.

Bringing that swing to tournament play is a totally separate challenge and something that has made Bryson’s experiment so impressive.

Bryson’s experiment shows that golfers who are bigger and stronger have a greater potential to create power in their swing. This is one of the reasons why TPI coaches are massive proponents of golfers doing work in the gym. That said, taking the opportunity to improve technically is equally as important as doing the work to improve physically.

We believe that every golfer should assess what their body can do and either build a swing that suits their physical capabilities or work with a trainer, strength coach or medical professional to improve those physical capabilities. While an amateur golfer doesn’t need to gain 40 lbs to squeeze a few extra miles per hour out of their swing, the benefits Bryson has reaped from increased strength and key mechanical changes are clear.