2025 CJ Cup Byron Nelson payout: Purse info, winner’s share

2025 CJ Cup Byron Nelson payout: Purse info, winner’s share

Gentler Ben: 25 years after emotional Masters win, Crenshaw reflects on the game that’s given him everything

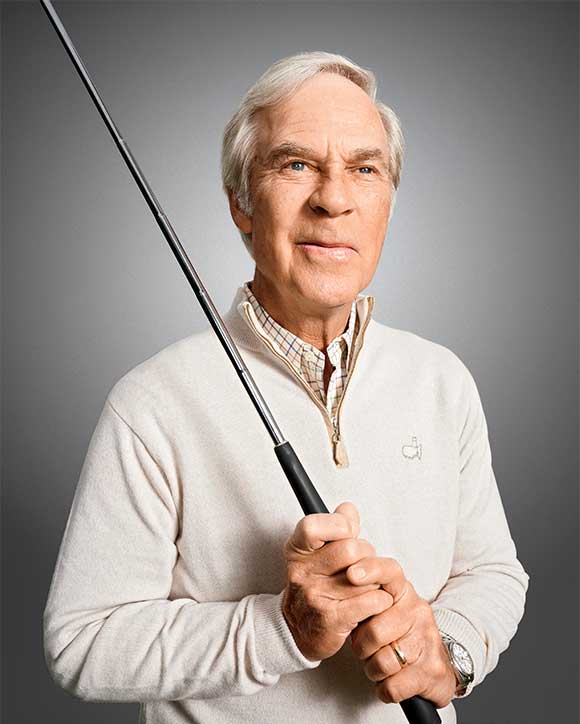

The television whirs to life and the years melt away. Sitting in his living room in a stately home in Austin, Texas, Ben Crenshaw is one of the game’s grand old men, with distinguished silver hair and a face etched by laughter and a lifetime of toiling under the sun. On the TV in front of him, Crenshaw is a quarter-century younger, with the blond mane and vigor of a silver-screen star. “Sooo handsome,” coos Julie Crenshaw, curled up on her favorite chair next to her hubby of 34 years. The final round of the 1995 Masters plays out before them, in all of its cinematic sweetness.

Augusta National has long been the game’s grandest stage, producing images made indelible by the imbued emotion. Tiger’s hugs with his father and son, Phil tearfully winning one for his cancer-stricken wife, Arnie joyously flinging his visor to the heavens… they are all woven into the fabric of the green jacket, but nothing will ever top the melodrama of Crenshaw’s victory in 1995, when he was guided by the unseen hand of his lifelong swing coach Harvey Penick, whom he had buried the day before the tournament began.

The victory secured Crenshaw’s place in the Hall of Fame, but its meaning transcends mere wins and losses. The whole golf world cried along with Crenshaw when he doubled-over on Augusta National’s 18th green, felled by the bittersweet emotions of having won for Harvey. The metaphysical overtones of the victory confirmed for many that Gentle Ben was more than just an everyday Tour player. With his palpable love for the game and warm embrace of its history, Crenshaw has always been a romantic figure—basically Shivas Irons with a better putting stroke.

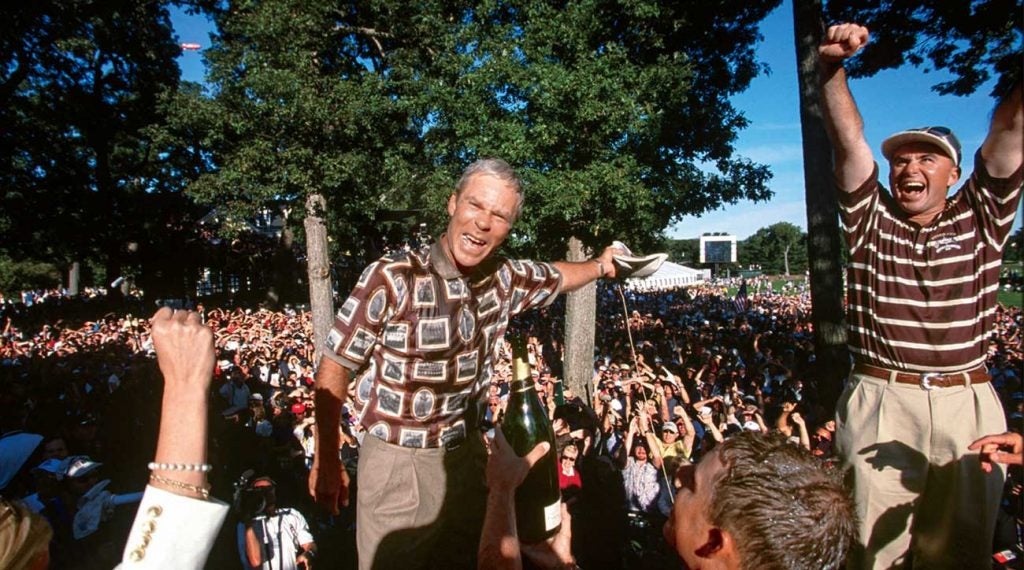

“There’s always been a little magic around Ben,” says Davis Love III, who finished second by a shot at the ’95 Masters. Indeed, at the 1999 Ryder Cup, Captain Crenshaw summoned the golf gods and the ghost of Ouimet to will the U.S. to an improbable victory. That was the exclamation point on a career that included 19 PGA Tour wins, among them the 1984 Masters. But it is one performance more than any other that has come to define Crenshaw and his unique place in the game.

“Even now, people still want to talk to me about ’95,” he says in his honeyed Texas twang. “It seems to have touched them in some way. When you’re in the middle of something like that, you’re not aware of the impact. That comes later.”

A quarter-century seems like the right time to look back and take the measure of the man and an unforgettable win. As the ’95 Masters plays out on the TV, there isn’t a dry eye in the Crenshaw living room. “I’ve had a lot of blessings in my life,” says Ben, a doting father to three daughters. “That week, what it meant to all the people who loved Harvey, what it meant to my family, that’s one of the big ones.”

Crenshaw was 10 years old when he took his first lesson at Austin Country Club from Penick, who had become the head pro at the tender age of 19, though he looked at least a decade older. (“He had so many wrinkles,” Jimmy DeMaret once said, “his face could hold a seven-day rain.”) The first time Penick put Crenshaw’s hands on a cut-down mashie, the teacher marveled at how natural his pupil’s grip looked. But the kid was in the clutches of another game: baseball. Before he became a successful attorney, Crenshaw’s father, “Big” Charlie, had been an all-Southwest Conference catcher at Baylor, and older brother, “Little” Charlie, was a Little League legend who would go on to play for the University of Texas. Crenshaw’s interest in golf was stoked by the arrival of a mysterious kid who one day joined Ben and his brother at the turn at Austin CC. He had thick glasses and was wearing slacks, of all things. The Crenshaw boys were turned out in T-shirts and shorts and had raggedy sets of hand-me-downs, but this kid had a big, red leather bag and sparkling new Wilson clubs. On the 10th tee he unsheathed an adult-length driver, took a cartoonishly long swing… and then gouged the earth 18 inches behind his ball, whiffing entirely. Helluva way to meet Tom Kite for the first time. He and Ben quickly became friends and rivals, with Penick ministering to both. Even as a tween, Kite put in marathon practice sessions, and his conversations with Penick were highly technical. The young teaching pro handled Crenshaw much differently. They would mostly chip and putt, and many lessons took place in the pro shop, waggling clubs while talking philosophically about the game. Says Crenshaw, “He would give me one thought to take to the course and that was plenty.”

When he was 15, Crenshaw had an at-bat against a six-five flamethrower named Bill Grief, who would go on to play in the big leagues. That strikeout pretty much ended Ben’s baseball career and soon he was making noise at national golf events, including the 1968 U.S. Junior Amateur at The Country Club in Brookline, Mass. That week was the first time Crenshaw heard the legend of Francis Ouimet. Around that time, he received as a gift The World of Golf, by Charlie Price, which stoked his interest in golf history in general and Bobby Jones in particular. As Crenshaw began visiting the game’s citadels to compete in USGA events, he would study the photographs on the walls and leaf through the books in the clubhouse. A love affair with the game was blooming. When the 1969 U.S. Open was played in Houston, Crenshaw worked for ABC as a spotter, sitting in the 15th hole tower and whispering details to broadcaster Bud Palmer.

Crenshaw stayed home for college and joined Kite at UT, putting together one of the best college careers of all-time: three NCAA individual titles and as a junior winning 11 of the 15 tournaments he entered. Crenshaw turned pro after that, in 1973, and promptly won the San Antonio Texas Open—the first PGA Tour event of his rookie year. The rumblings grew louder that the Next Nicklaus had arrived. But Crenshaw’s beloved mother, Pearl, died of a heart attack at the end of his rookie year. Her youngest son went into a deep funk and wouldn’t win again until 1976, the beginnings of a feast/famine career.

By the time Crenshaw arrived at the 1984 Masters he was considered a maddeningly talented tease. He was going through a divorce and limping on a broken bone in his foot that went undiagnosed for years, its origins a karate kick of a metal trash can at Colonial. (When Austin sportswriter Dick Collins first used “Gentle Ben” in print, it was meant sarcastically.) At 32, Crenshaw had won nine Tour events but kicked away the ones that really mattered: a playoff loss at the 1979 PGA Championship; runner-up finishes at Augusta in ’76 and ’83; the ’75 U.S. Open, where he toed a 2-iron into the water on the 71st hole and lost by a shot; the ’79 British Open, where he suffered a misadventure in a greenside bunker and made another 71st-hole double-bogey to finish second.

But on Masters Sunday in ’84, Crenshaw finally unleashed all of his want and will, with a birdie barrage that included an instantly famous 60-footer on the 10th hole. In victory his thoughts went to two guiding lights, Big Charlie and Emperor Jones. “It was such relief and joy,” Crenshaw says in Two Roads to Augusta, cowritten with Carl Jackson and Melanie Hauser. “It was something my father and I could share together. His little boy had just won the Masters, the finest tournament we knew. I won Bobby Jones’s tournament.”

When Crenshaw arrived back in Austin, at 1:30 in the morning, a stooped old man with a cane was waiting. “I’m mighty proud of you,” Penick said.

******

The decade that followed the Masters triumph was very much like the one that preceded it: eight Tour wins and more heartbreak in the majors, including a quartet of close calls around Augusta National. At the 1985 L.A. Open, Ben chatted up a beautiful blond in the gallery, and he wound up marrying Julie ten months later. That same year he entered into another meaningful long-term relationship, as he and Bill Coore founded their course design firm.

Says Coore, “I’ll never forget the day Ron Witten”—the dean of golf course architecture writers—“came to Austin to interview us. He put a tape recorder on the table in the men’s grill at Barton Creek and his first question was ‘So, what’s the name of the company?’ We had not talked about it. I know that seems idiotic, but it had just never occurred to us. There was an awkward silence and Ben blurts out, ‘Coore-Crenshaw.’ Think about that. Could you name me one other of the world’s best players in his prime who would have done that? I don’t think you could. I mean, I was an unknown. Anyone else would have said Crenshaw Course Design. Or Crenshaw & Associates. But he put my name first, which tells you a lot about Ben.”

Together, they began redefining the modern aesthetic, marrying a love of links golf and an appreciation for classic courses with a dedication to finding and preserving the most natural of settings. (Work began on the seminal Sand Hills Golf Club, in Mullen, Neb., in 1990.) As Crenshaw poured his passion into the design business, his golf game suffered accordingly. When he turned 40, in 1992, he was in the midst of a drought during which he won only once in the span of four years. But in his early 40s, Crenshaw enjoyed a little renaissance, leading his pal Dave Marr to quip, “Ben, you’re on your 21st comeback.”

In the spring of 1995, Penick’s health took a turn for the worse. He was now a figure of national prominence, after the 1992 publication of the wildly popular Harvey Penick’s Little Red Book, a slender volume packed with so much homespun wisdom that Sports Illustrated dubbed Penick “the Socrates of the golf world.” In 1995, the New Orleans Classic was played right before the Masters. Penick, then 91, was hospitalized early that week. After missing the cut, Crenshaw considered flying home, but Harvey talked him out of it so he went straight to Augusta. From his hospital bed, Penick monitored the New Orleans telecast closely. One of his close friends and protégés had been Davis Love II, and Penick gave occasional lessons to his talented young son. A dip in form had prevented DL3 from qualifying for the Masters. New Orleans was his last chance to win and get in, and Love summoned an inspired performance. Says Crenshaw, “The people in the hospital room with Harvey told him that Davis had won and he said, ‘That’s great,’ and he clapped a few times and then he passed away. Isn’t that something?”

ADVERTISEMENT

The Crenshaws were dining in the Augusta National clubhouse with Pat Summerall and club chairman Jack Stephens when the awful news came by way of a note discreetly slipped to Julie, who then took her hubby onto the porch where they cried together for a solid 15 minutes. With the funeral set for that Wednesday, Ben still had two days to go through the motions of preparing for the tournament. His trusty caddie, Carl Jackson, who had been on the bag for every Masters going back to 1976, watched a couple of swings and was shocked by his boss’s frazzled tempo. “Slow down, slow down, you look like you’re trying to kill a snake,” was Carl’s memorable description. He also diagnosed that Crenshaw needed to put the ball back farther in his stance and make a tighter shoulder turn. Just like that, Crenshaw turned back the clock to when he was a free-swinging prodigy.

On Wednesday morning of Masters week, he and Kite rose with the sun, flying back to Austin to serve as pallbearers at Penick’s funeral. They returned that evening and Crenshaw went straight to the range. It was a beautiful twilight, and Gentle Ben found some peace of mind at the deserted range. His swing was still there, too.

The next day he opened with a solid 70, good for 16th place, four strokes off the lead of Phil Mickelson and the defending champ, José María Olazábal, and three shots back of a guy named Nicklaus. (Tiger Woods, playing in his first Masters, posted a 72.) “Over the years I had shot myself out of quite a few tournaments because I lost control of my emotions,” Crenshaw says. “The remarkable thing about that week is how uncluttered my mind was. I felt peaceful, especially after the bad shots.”

In the second round, Crenshaw fired a 67, the second-lowest round of the day to surge into a tie for fourth, one stroke ahead of Love, who says, “You could feel the emotion building. The way I got into the tournament, my dad’s connection to Harvey, obviously Ben’s relationship to Harvey, all of that was in the air. You couldn’t help but feel like we were building toward something special.”

On Saturday, Crenshaw put together a steady 69 to move into the lead, alongside a youngster named Brian Henninger. Mickelson and Fred Couples were among those who were one shot back, while Curtis Strange was in a group two strokes behind. (After a 71, Love trailed by 3.) The leaders wouldn’t tee off until 2:41 on Sunday. Little Charlie flew in that morning and helped his brother pass the time by chipping pine cones with him in the yard of their rental house. Getting dressed for the day, Ben razed a few ghosts by donning a shirt emblazoned with images of Bobby Jones from his Grand Slam campaign in 1930. (This would be the inspiration for the shirts the U.S. team wore for Sunday Singles at Brookline.) Before heading to Augusta National, he walked to the end of the driveway and stood motionless for half an hour, doing a kind of upright meditation.

“I prayed for strength,” he says. “I prayed for acceptance for whatever the day might bring.”

All week long, Julie had been talking about “Harvey bounces”—the little strokes of good fortune that kept propelling her husband forward. On the second hole of the final round, Crenshaw hooked his drive but enjoyed a Harvey bounce off a tree, which kept him in play instead of going deep into the forest. He went on to birdie the hole, and then number 6, too. The Sunday telecast begins with Crenshaw in the back bunker at the 7th hole, from where he saves an improbable par.

“Shoot, I wouldn’t want to have to play that shot again,” Crenshaw says from his living room. Up ahead on the 8th hole, Love makes a birdie to get to 10 under and tie Crenshaw for the lead, but something else catches Julie’s eye. “Pleated pants and mustaches were still in, huh?” she teases. Curled up in her lap is Francis the cat, named to honor the 1913 U.S. Open champ. Both Julie and Ben are drinking wine out of plastic Masters cups that they have brought home over the years just like the starry-eyed fans do. (The fancy crystal that comes with making Masters eagles is on display in Ben’s incredible office, which is packed with ancient leathery books and many other treasures.)

The telecast plays on. On the 13th hole, Crenshaw redeems a mediocre chip by burying a curling 20-footer for birdie. He is rightfully celebrated as one of the greatest putters in the game’s history, but this prowess is not built on technical precision. “You can’t copy his stroke and you wouldn’t want to,” says Justin Leonard, the hero of Crenshaw’s 1999 Ryder Cup team. “He has different technique on different putts: He’ll draw putts, slice putts, hit the ball on the toe to deaden the speed. For him, it’s all about feel. He has the best speed control I’ve ever seen and that’s all he cared about, not the way it looked. It’s fascinating to spend time with him because his approach is so different from everybody else—they’re all trying to groove the same stroke over and over.”

On the 14th hole Crenshaw gets another Harvey bounce, his pulled tee shot glancing off a tree back toward the fairway. “Can you believe that?” he says, voice rising. “I played well and stuck in there. I had belief in my game. But there was something else at work that week.” While Crenshaw is making a disappointing par on 15, Love is finishing off his rousing 66, keeping him tied for the lead at 13 under. Crenshaw steps to the tee of the par-3 16th hole knowing it’s his last best shot for a birdie to break the tie. He launches a high draw with a 6-iron and his ball catches the slope, feeding toward the hole. “Go on!” Julie shouts, as if she doesn’t already know the outcome. Now Crenshaw is hunched over a do-or-die 5-footer for birdie. What’s his secret to making such a putt?

“Stay down.”

That’s it?!

“Yep, that’s it. Stay in your posture and let the putter swing freely.”

Up on the screen he does exactly that and the green jacket is suddenly within his grasp. On the diabolical 17th, Crenshaw faces another birdie putt, this one a 15-footer that is a brutally fast left-to-right slider with 18 inches of break. When he pours it in to all but ice the victory, the Crenshaw on the screen is stoic and all business. Reliving it in his living room, he can’t entirely swallow a smile. “Might be one of the best putts I ever made,” he says softly.

As the final hole plays out on the television, both Ben and Julie are taking deep breaths, knowing what’s coming. As Carl Jackson said recently, “All that happened like in a dream. I just got there and said a few words to him. He wasn’t crying, he was boo-hooing.”

******

Crenshaw never won again. “I couldn’t summon the emotion,” he says now. But he has remained a vital part of the Masters and the larger golf world. In 1998 he took over from his hero Byron Nelson as master of ceremonies at the Tuesday night champions dinner. Crenshaw is a welcoming presence who dispenses little history lessons along the way. He pooh-poohs the notion, but when Nicklaus, 80, relinquishes his duties as honorary starter Crenshaw is the natural successor.

The ’99 Ryder Cup was an epic victory lap and brought this golf historian full circle back to The Country Club, where he had first become entranced by the Ouimet legend at the U.S. Junior three decades earlier. “I’m a big believer in faith, and not even necessarily of the religious kind,” says Jeff Maggert, a member of the ’99 U.S. team. “When you believe so hard in something, it has a way of coming true. Ben believed in the history of that place. It was very real to him. He believed so much, he made us believe, too. He manifested that outcome because his faith was so strong.”

In the end, that Ryder Cup was a triumph of the interpersonal. “He’s very much like Arnold Palmer,” says Maggert. “When Ben walks into a room, he makes everybody feel special. He always has time for people, always a kind word. There is an instant connection and camaraderie. It might be just a short interaction, but you always walk away feeling good.”

Leonard also mentions the King in trying to capture Crenshaw’s legacy: “Arnold had a bigger career and came along at a different time, but in the end Ben’s impact might be just as big because of his design work. All those great courses he’s built will live on forever, hopefully. Arnold is always celebrated for growing the game, but what could be a better way to grow the game than to create beautiful, fun courses that make golfers want to play more golf?”

The man Crenshaw frequently collaborates with, Bandon Dunes owner Mike Keiser, calls him “the archangel of golf,” adding, “His influence is massive. What Ben likes in a golf course, what he values, has now been exported to every corner of the golf world. He has changed the tastes of golfers everywhere for the better.”

In his hometown Crenshaw has built his own private Eden, the Austin Golf Club, where he hangs out nearly every day, running herd on ornate betting games on the practice putting green. But he advocates for all of the town’s golfers: His Escalade has a “Save Muny” bumper sticker, and Crenshaw has been a fierce advocate for protecting Lions Municipal Golf Course. Not for nothing does Leonard call Crenshaw, “the mayor of Austin.”

At his favorite little Mexican restaurant Crenshaw knows every busboy by name and greets them warmly. He’ll also introduce you to a fellow at the next table named Tito, who founded the eponymous vodka label. Over margaritas and enchiladas at dinner, Crenshaw is in an expansive mood, still buzzing from having just watched the ’95 Masters telecast for the first time in years.

“Sometimes it doesn’t feel real,” he says. Actually, it’s better than that. It’s mythical.

To receive GOLF’s all-new newsletters, subscribe for free here.

ADVERTISEMENT