There’s a story that Jordan Spieth tells about Tom Brady.

They’re playing Augusta National and the match is tied going to No. 18. Brady’s getting a stroke, but he finds the front bunker with his approach and makes bogey. Spieth, meanwhile, stuffs his second shot in tight for a kick-in birdie. Spieth wins, 1 up. Brady doesn’t take it well.

“You’re supposed to go in at Augusta and have lunch and hang out, and he didn’t say a word to me for like an hour and a half,” Spieth told Dan Patrick later. “I feel like I’m very, very competitive. He is the most competitive human being I’ve ever met.”

There’s a story that Keegan Bradley tells about Tom Brady.

Bradley, who grew up in New England and remains a diehard Boston sports fan, is on vacation at Baker’s Bay in the Bahamas when he runs into Brady. They set up a match. Bradley agrees to give Brady, who plays off roughly an eight handicap, 12 shots.

“And I win the first hole. I go, ‘TB, I’ll give you a buyout if you want,’” Bradley said on GOLF’s Subpar podcast. “I just start chirping. And then he runs off and plays the next 14 holes in four under par. Beats me 6 and 5. He’s really good. I couldn’t believe it. Those competitive juices kicked in and he smoked me.”

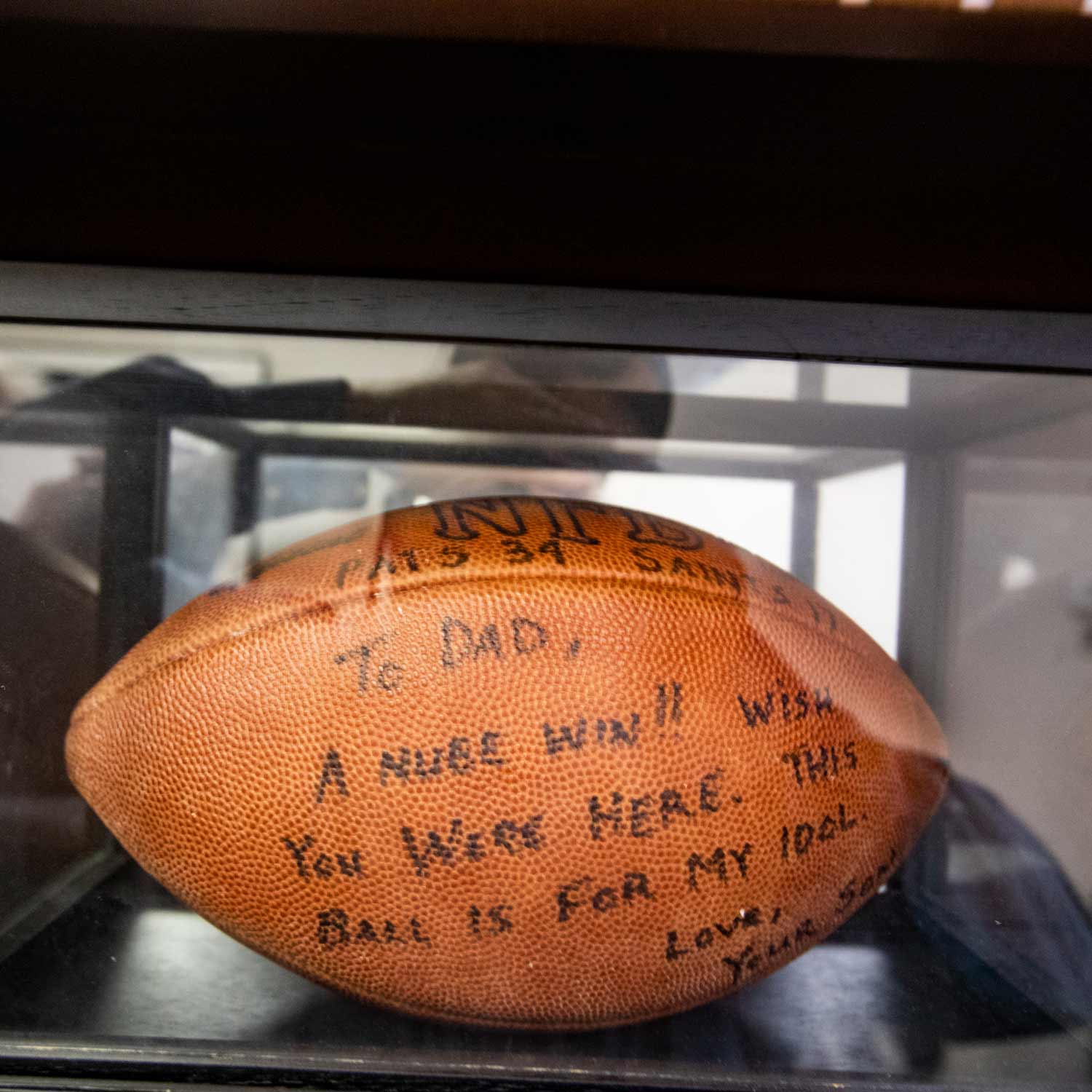

There’s a story that Tom Brady’s dad tells about Tom Brady.

Tom is four and they’re playing their first-ever golf tournament together. The format is alternate shot, so they’re taking turns. On the 12th green, Brady Sr. holes a long putt. His son starts crying—he wants to hit every shot. Being deprived of the chance to putt feels like a betrayal. On the very next hole, it’s Brady Sr.’s turn to putt again, and this time he lags one to tap-in range. His son walks up to the ball and smashes it away from the hole, taking a chunk out of the green in the process.

Later, Brady Sr. asks his son why he hadn’t just tapped it in. Tom’s answer? He wanted to hit the ball hard. Their team, Brady Sr. recalled to ESPN, finished last.

In writing about Tom Brady the football player, there’s inherent pressure to build on the legend. That’s our instinct with great athletes: We take stories from their lives and trace lines directly to their lofty perch at the pinnacle of sport, suggesting it’s all connected. At just four years old, Brady wanted the ball. Demanded the ball. But that’s a myth-making stretch.

This was something better: the story of a kid just being a kid.

There’s freedom in relaying Tom Brady golf stories. Some, for sure, involve jock heroics, but there’s no pressure on them to make the case for Brady’s mastery of the game. The beauty of golf is what it teaches us about the people who play it.

On a break from training camp and over the phone from his home in Tampa, Fla., some four decades later, Brady thinks back on the putter meltdown and sighs.

He tells me he admires Bill Murray for the way he approaches pro-ams. Whatever he shoots, he’s keen to enjoy the moment.

“That’s probably a good lesson for us all,” Brady says. “Find the joy in it and don’t worry too much about the score, the final outcome.”

I point out the obvious: Brady isn’t wired that way. There’s zero chance he can be that guy, right?

Reluctantly, he agrees. “I always have these grand illusions that things are going to go well when I get out there on the course, and they never do. So I’m trying to transition that mindset to focus on more of an experience as opposed to, y’know, trying to go out there and shoot record scores.”

That new mindset? “Just go out there, enjoy it, and if you hit some good shots, great,” he says. “Enjoying the company and being with people, y’know, that’s the best part about golf.”

Good luck with that, TB.

At the very least, Brady begins every round with a positive attitude. He has a running joke with frequent golf buddy Jimmy Dunne that whatever the weather brings the morning they’re supposed to play, they embrace it. The two have a saying: It’s just like we like it.

“Golf is a very elusive sport,” Brady says. “You know, it’s there one day and gone for the next three months. But that one day—you’re trying so hard to get back to that feeling. And it’s very rare that you find it. And when you do, you love to get more of it.”

For Brady, who was raised with three older sisters, golf initially meant a chance for time alone with his father. He was raised in San Mateo, Calif., about 20 miles south of San Francisco, and the two of them would travel around the Bay Area, playing different courses. “It was just a great thing to do growing up,” Brady says. “You were out in nature, and you got some exercise and got a lot of bonding time.”

I’m curious about what he thought of golf as a kid. Where I grew up, junior golf didn’t have the reputation of being “cool.” He shrugs off that idea.

“I think being cool is being authentic to who you are,” he says. “It’s just doing what you love to do and really owning it. I always thought golf was cool.”

There’s a story that Tom Brady’s college résumé tells about Tom Brady.

First, consider the fact that he had a résumé in college. Brady’s NFL future was so uncertain that he worked summer internships with Merrill Lynch before his junior and senior seasons. But below that Merrill entry on his CV are jobs at golf courses, including “sales representative” and “course ranger” and “assistant clubhouse manager,” first at the Polo Fields Golf and Country Club in Jackson, Mich., then at his alma mater, the University of Michigan, whose golf course was across the street from the Big House. The descriptions read like any college kid looking to inflate limited job experience: Developed interpersonal skills and exemplified flexibility in order to better serve club members.

On the phone, Brady laughs. “I worked as a ranger. I worked in the pro shop. Y’know, it was my way to play free golf, because none of us had any money in college.” He remembers it being fun. And the peak of his game. “Over the years my golf got worse as my football got better.”

A lot has changed in Brady’s world since then, and not just on the football field. The kid working for free rounds in Ann Arbor now juggles memberships at Riviera, Seminole, The Country Club and an assortment of swanky Discovery Land Co. escapes. His playing partners include U.S. presidents. He and his dad take father-son golf trips with Rory and Gerry McIlroy. He plays Augusta National with regularity. He also competes in The Match series, putting his game on display for a television audience of millions to see.

Now, he’s in the business of golf too. The launch in January 2022 of an all-new golf-and-lifestyle apparel company, BRADY Brand, guarantees that the game will be more than an offseason pastime; it’ll be an important part of his future.

It’s funny to think that a career that began in college athletics now employs college athletes. BRADY Brand has signed some promising collegiate golfers—including Cole Hammer, who has since turned pro, and Wake Forest’s Michael Brennan—to NIL (Name-Image-Likeness) deals. They’re working to reach an audience on TikTok. None of this would have made sense to Brady in the summer of ’99, when he was making $10 an hour parking golf carts. But, in many ways, that’s the point.

“Cole and Michael were really fun to work with,” Brady says. “From the beginning, this was a brand we wanted to work for the next generation of athletes. So many of these kids now have opportunities with the new deals to take their brand to the next level. And I think it’s been really fun to collaborate with these young athletes and see their dreams come true.”

There’s a story that Bill Belichick tells about Tom Brady.

They’re playing No. 6 at Pebble Beach, and Brady’s ball is on the edge of a cliff. This is the AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am, so every shot counts—but Brady’s pro partner is already safely in position, so his score is unlikely to matter. Watching Brady, you wouldn’t know it. He saunters over to the cliff’s edge, surveys his lie and asks his caddie to literally hold onto him so his swing won’t send him tumbling into oblivion. Belichick, who coached Brady for 20 seasons with the New England Patriots, can’t believe his eyes.

“I see a starting quarterback, a Super Bowl MVP, a league MVP literally hanging over the side of the cliff, probably 200 to 300 feet above the ocean, trying to hit a golf ball that’s a pretty meaningless shot,” Belichick told NFL Network. He breathed easier when Brady’s ball—and body—returned to terra firma.

In golf, it’s rare to tempt fate like this. In the NFL, it happens every time Brady—who, at age 45, is deep into his 23rd pro season and his third with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers—steps on the field. But, then, golf isn’t much like football. I press Brady for any cross-sport similarities. He’s more drawn to the differences.

“In football, you want to get really hyped up and have your emotions to a fever pitch,” he says. “You can get as emotional as you want. It’s going to lead to more speed, more energy, more enthusiasm. Golf is very different. I don’t know how they do it. When you get hyped up in golf, how do you stay calm?”

There’s another significant difference: Brady is good at golf, but he’s great at football. He has played both in front of large TV audiences. So far, the football has gone better. How do the experiences compare?

“I get so technical when I think about golf,” Brady says. “In football, I don’t really get technical. I actually get very simple. And I think good golfers probably make it very simple too.”

The simplicity, he says, comes from practice; from mastery of technique and fundamentals and training. It makes executing under pressure that much easier.

“Let’s say you’re not good at something. Now you have to use 80 percent of your conscious brain to focus,” he explains. “As opposed to if you could spend 100 percent of your brain focusing on 5 percent of the unknown, which I think is great. I think that’s the difference in football. I can do so many things in my subconscious that it’s easy to focus on a small detail with 100 percent of my focus.”

There’s a story the staff at Silo Ridge Field Club tells about Tom Brady.

Brady once had a home inside the gates of the Upstate New York golf retreat built by Discovery Land Co. He’s paying a visit there, but he’s short on time. Brady is always short on time. In this case, he’s short on daylight too. But Justin Marano, the pro, has offered up an evening lesson. They set up golf carts along the range, lights on, illuminating his hitting area so Brady can get some reps in, pummeling one ball after the next into the night.

“I try to take advantage of it where I can,” he says, laughing at the memory of his late-night session. Still, Brady admits the lessons don’t always stick, even from a trusted voice like Marano.

“I’m very vulnerable to swing tips,” he tells me. “Anyone who gives me any golf suggestion—unfortunately, I feel like I’m listening. But I think the best thing is to find one person and try to work with them to turn your swing around.”

Brady downplays the idea that he’ll ever work hard at golf. But that ignores the fact that he works hard at everything. Not caring about golf is antithetical to his approach to life.

“Just the competitiveness that he has, I feel like he’s got to find a hobby or something, because he’ll go nuts sitting still,” said Spieth during Brady’s short-lived retirement this off-season. It turns out the retirement hobby he found was unretiring to play football—for one more year, at least.

I ask Brady how his relationship with the off-season has changed. I wonder if he’s more efficient with his preparation, and if that frees up time for anything else. He talks about the process of evolving in life, about shifting priorities and the need to manage them. “As we change, as we all grow, there’s different stuff that comes up,” he says. “Our schedules get busy and our dynamics change. I’m looking forward to having a whole life after football that feels like an off-season. That would be enjoyable for me.”

Brady admires the top-tier pros from across sports, like Steph Curry and Tony Romo, who work hard on their golf games and carry plus handicaps. But he insists he won’t be one of them.

“After my football career is over, I’m not going to take sports very seriously at all,” he says. “It’ll just be for the pleasure and joy of playing them. I feel like I’ve got all my competitiveness out of me in sports.”

Don’t believe him.

There’s a story that Tom Brady tells about Tom Brady.

He’s not afraid to overhype it, either. “That was one of the all-time great moments in golf that took place,” he says. He’s playing the par-4 17th at Cypress Point with New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, part of a nine-hole challenge they play annually. Brady tees it up on the oceanside hole and stripes his drive—in the direction of the Pacific.

“I slice it, it hits the rock and bounces up” onto the fairway, he says. Friedman can’t believe it. “He’s like, ‘What?! You’ve gotta be kidding me! You’re so lucky!’ Blah, blah, blah.”

Brady grabs 9-iron.

“I basically hit it so thin that I’m like, ‘Oh, God, get down.’

It takes one hop, two hops, hits the flagstick and goes in the hole. I was running around. Two of the worst shots I’ve hit, and it ends up going in for two. That was one of the great, funny memories I’ve had in golf.” Is there a football equivalent to a story like that? “Throwing to Randy Moss over the years,” he says. “Or to Mike Evans. You can really get away with some bad throws.”

His Cypress deuce sounds like a tough golf story to beat. But when I ask Brady for his dream day of golf, he pauses. Links golf is on his bucket list, he says; golf in Scotland and Ireland. But when it comes down to it, the where isn’t particularly important to him.

“I feel like it’s just a great activity to be together, and I’m really looking forward to having some decompression fun,” he says. “To go from the seriousness of sports, which has been my profession, to a more sustainable way. That’s with family—and getting to play with them and really enjoying it.”

The author welcomes your thoughts at dylan_dethier@golf.com.