Blame it on the Kodak disc camera. It was 1984 and I was 12 years old. A skinny kid with shaggy hair and, if the pictures are to be believed, a lifetime of poor taste in clothing. Dad and I were in the gallery by the fairway bunker on the 18th hole at Augusta National Golf Club, a postcard-perfect day where I was desperately trying to take a picture of a golfer long since lost to memory as he wandered up the pristine fairway during a weekday practice round. What I failed to realize, however, was that his playing partner had pulled his tee shot left and the crowd had parted to clear the way for his second shot. Like any young boy fascinated by the sight of his idols, I somehow failed to hear my father’s voice when he called my name. Twice. Suddenly I looked up to see Johnny Miller glaring at me — I was the only person standing between him and the green with dozens of patrons having created a 20-foot wide “V” to allow him room to take his second shot.

To say it was an embarrassing moment in the life of an adolescent would be a journalistic understatement. Luckily it was a practice round and no one took away the tickets we had purchased that morning at the Augusta National ticket counter. You read that correctly. Once upon a time people arrived early, parked by the Green Jacket restaurant, dashed across Washington Road and bought a ticket to watch a practice round. Moments after purchasing those tickets, Dad and I walked onto hallowed ground, my Kodak disc camera in one hand and a dime store faux leather autograph book in the other. It was my first trip to the Masters.

My dad fostered a love of golf at an early age, taking me with him to play a number of courses in middle Georgia when I was in elementary school. My first set of clubs were Nicklaus Golden Bears, in the days when all woods had steel shafts but were otherwise still made with wood. Since then I’ve upgraded my equipment a few times and have had the good fortune to play some of the best courses in the world, from Pebble Beach to Royal Portrush and even a couple that prefer to remain off the golfing radar grid. But one course has always remained near and dear, with its legendarily affordable snacks during tournament time and the opportunity to rekindle old memories and even make some new ones. As every fan of golf will attest, there is still nothing quite like being at the Masters.

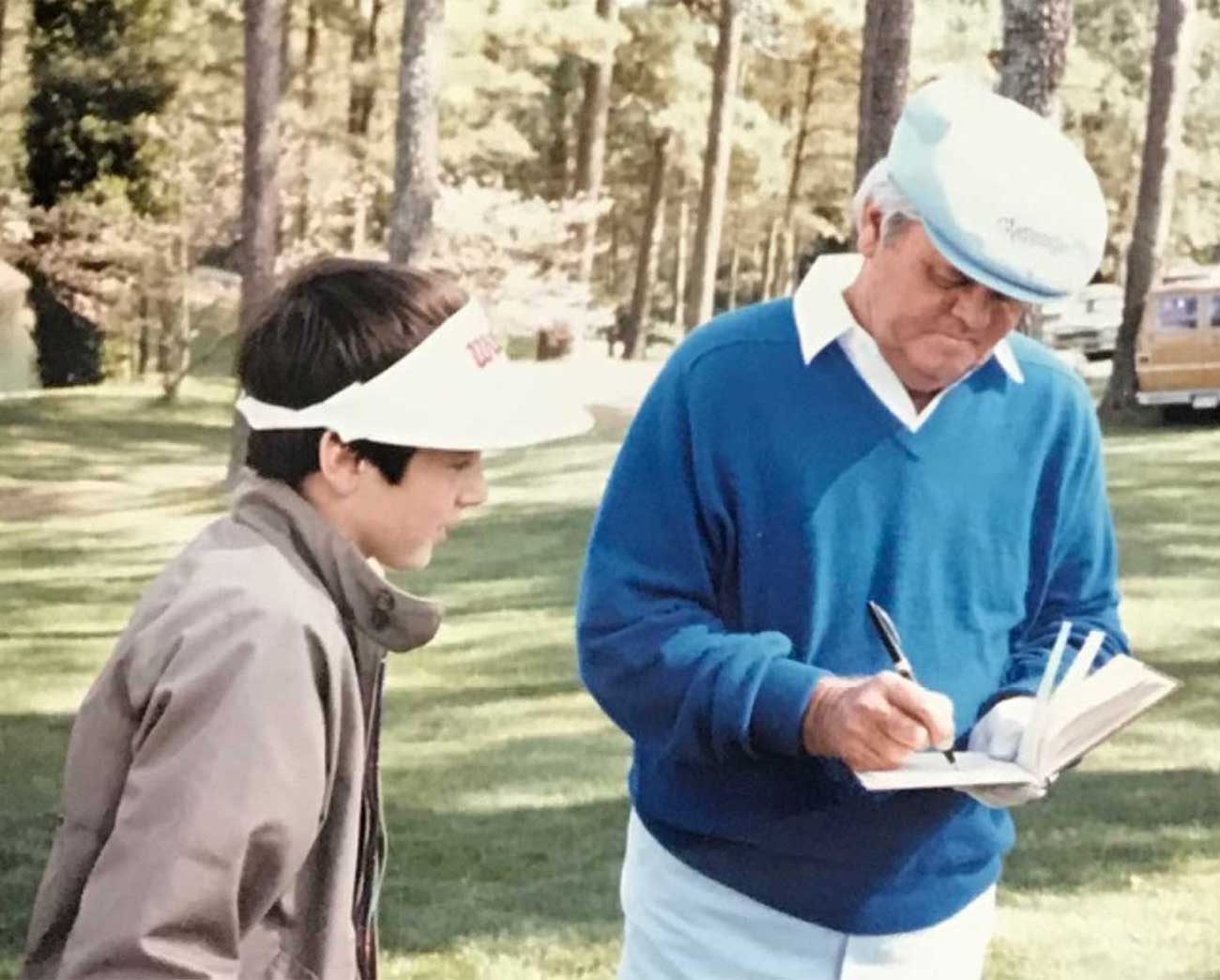

When Tiger wrapped up his historic win last year, I reflected on my own Masters journey, as so many fans of the game undoubtedly found themselves doing that Sunday afternoon. Those early years with my father were innocent and carefree. When an older gentleman finished hitting balls on the practice range one morning in 1985, Dad told me to walk down and ask for his autograph. It was obvious this player had no chance of winning the Masters at this stage in his career, but his charm and congeniality were almost otherworldly as he signed his name and posed for pictures. Looking at my autograph book after a moment to decipher, I asked my father for a history lesson: “Who is Sam Snead?”

* * * * *

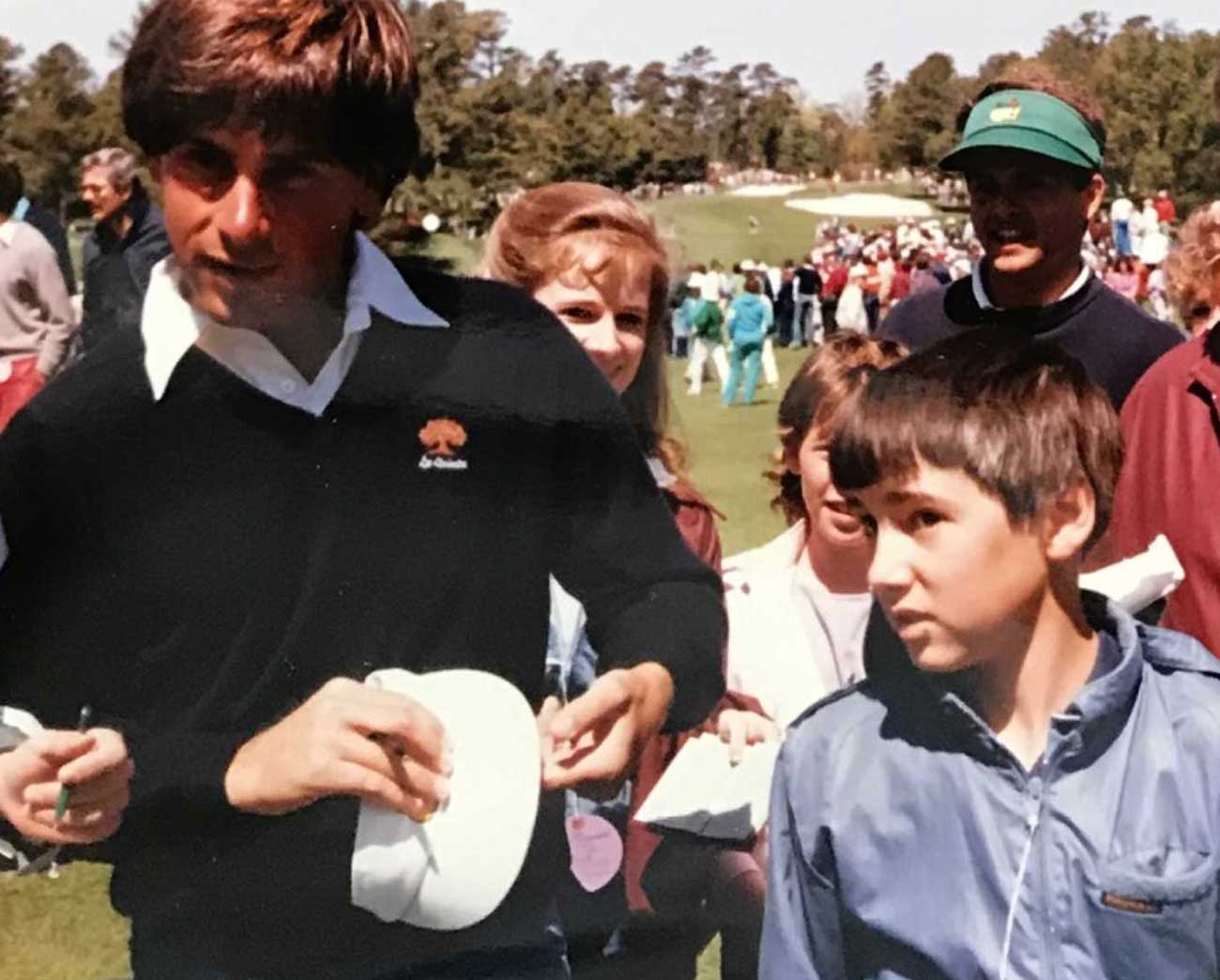

Last year I asked my mother, a notorious collector and filer of thousands of family photos, whether any of the pictures we took from my childhood days at the Masters still existed. Four minutes and one closet visit later, she handed me six packages containing pictures from those boyhood trips with my father from our home in Macon, Ga., to Augusta in the ‘80s. The memories came flooding back. I recalled being handed the golf ball that won the Par 3 Tournament in 1985. (Thank you, Hubert Green.) Tom Watson making a deal to sign my autograph book as he walked off the 10th green — but only if I carried his driver to the 11th tee. Requesting the autograph of a young golfer who pulled his clubs out of the trunk behind the driving range and then attempting to pronounce the name: “Olazabal.” (Not even close.) They were all there — from Snead to Jack Nicklaus to Ben Crenshaw and everyone in between.

Then there came a period I call The Void. Those Masters trips faded by the end of high school and the daily ticket counter became a remnant of Augusta National’s folkloric past. College held its share of distractions and my interest in the game, and in the Masters, took a back seat to other pursuits. Sure, we played a few rounds here and there. Dad and I teed it up on occasion, but the numbers in my sights in the early 1990s were more about GPA and less about an index by the USGA. I needed to get into medical school.

One of the curious twists of fate growing up in Georgia and aspiring to become a physician is that one of the oldest medical schools in the country just so happens to be located in the city of Augusta. The Medical College of Georgia was founded in 1828 and, as a state school with an early admissions program, it was a natural target for an undergraduate from Emory University hoping to practice medicine. Crawford Long was the first physician to successfully use ether as an anesthetic agent in a surgical procedure in the back woods of Georgia in the early 1800s, and I now wanted to make a career out of the legacy that Long left behind as an anesthesiologist. A decade after attending my first Masters tournament, my father, mother and I were together again in Augusta, this time moving furniture into a rental home I was sharing with my two best friends from high school in Olde Town.

There would be no golf that first year of medical school. My clubs, now modernized to a knockoff Big Bertha driver complemented by a set of Spalding Executive irons, had made the trip to Augusta only to gather more dust in the fall of 1994. But then the first summer arrived, and with it the exploration of several local golf courses. Our primary venue was Forest Hills Golf Club, where Bobby Jones famously began his quest for the 1930 grand slam by playing there in the Southeastern Open. Greens fees were affordable and somehow, despite 90-degree temperatures and a leather bag whose strap should have been decorative rather than functional, my friends and I walked that course dozens of times in the summer of 1995 and over the subsequent three years.

Golf was once again a part of the conversation. And in Augusta, there was really only one conversation taking place by the beginning of April each year. Long-lost friends from college suddenly found your phone number. Our living room during the week of the 1996 Masters was filled with sleeping bags and people in various states of disarray, repair and recovery. They road-tripped from myriad directions to take advantage of a free place to stay, Masters tickets (usually) in hand passed along by generous family members or friends with Augusta connections. I went home for a few days that week and returned to watch the epic collapse of Greg Norman on Sunday, trying not to think about who or what had occupied my room the past few nights. Our medical pursuits were increasingly balanced by our conversations about, and our rekindled interest in, the game of golf.

In a century and a half of existence, the Medical College of Georgia had a number of great traditions. One glorious ritual, however, stood out above them all and was informally passed down within the student body. There was always a need for medical volunteers at the Masters, and those positions had been entrusted to a handful of medical students for decades. Nine students, to be precise — six fourth-year students and three third-year students. As those third-year students entered their final year of medical school, they reached out to three additional classmates and three students in the class below. And so the cycle continued. No applications. No background checks. Just good friends looking out for each other, passing along a quiet but treasured opportunity.

In early 1997, I got a phone call from a classmate who had just been asked to join the first-aid group for the Masters that year. The fourth-year student who reached out to him suggested he grab one more friend, and if I didn’t have any plans, would I be interested? Chris didn’t have a chance to finish the question before I answered. Fast forward a couple of months and on April 7 I parked in the assigned lot near Amen Corner, walked across the course to the first-aid building near the players’ parking lot, and reported for duty.

Our group served as first-aid volunteers the entire week, starting Monday morning and wrapping up Sunday evening after the awards presentation. Four groups of two students were assigned a spot on the course to park a first-aid golf cart each day. We had walkie-talkies with ear buds and strict instructions to minimize any chatter that wasn’t related to a medical response. One person was assigned to the first-aid building itself, a designated “runner” who drove a van to a nearby hospital if needed. At the time, like most Masters tales that may arguably be seeded with a kernel of truth, the story was that the National did not want sirens or flashing lights on the property — all emergencies were to be handled quickly and discreetly. When activated, we were to move, triage, and return to our position when a response was complete. No actions or noise that would make the news or disturb the flow of the tournament.

There was no financial compensation for the first-aid volunteers and the hours were long and sometimes, believe it or not, a bit tedious. Luckily two of the posted positions were within eyesight of the Par 3 greens of 12 and 16. Running bets were placed between partners throughout the day for closest to the pin, low score amongst the playing group, shots in the water, and just about anything else we could dream up. Patrons would occasionally ask for a ride up the hill (strictly forbidden) and at times a physician alum of the program would stop by to chat and reminisce. Otherwise, we watched the practice rounds early that week and finished each day debating who would win the 1997 Masters over a late dinner and drinks.

That debate, needless to say, ended rather quickly. Late one afternoon during the practice rounds I had been walking back to the parking lot and happened to see a few people milling around the 6th hole. I had my camera with me and paused to look up at the tee as I crossed the fairway. The course was officially closed but players sometimes wandered back out after hours to squeeze in a few more holes. My picture of a young Tiger Woods walking down the hill with the runner-up from 1996 is still one of my favorite images from that magical tournament.

History, needless to say, was made that year, with our first-aid group enjoying a front-row seat. As Woods made his way to the 18th, we were all released from our outlying posts and joined the patrons around the green to watch the conclusion of his record-setting performance. It was tough for me to leave that evening, with the sun setting over the iconic 18th green scoreboard and a drive back to a General Surgery rotation in Atlanta now looming, but there was solace in knowing that we would return a month later. None of us would dare miss our tee time at Augusta National.

Like kids in a candy shop, our group reunited in May of 1997 to join dozens of other volunteers in another wonderful Masters tradition — the “play days” hosted by Augusta National as a generous way of thanking everyone for their service during the tournament. We were assigned tee times in advance and told we could arrive when the gates opened if we wanted to play the Par 3 course prior to our round. Which we did. Twice. Southern hospitality abounded that day as we played our round, enjoyed a catered barbecue lunch, and had the opportunity to explore the clubhouse, which was open for all volunteers to visit. The Kodak disc camera was long gone, the pictures from that day limited only by the number of shots we could capture on a roll of 35mm film.

In 1998 our three fourth-year students repeated the tradition of adding six new friends to the group, and we all watched Mark O’Meara sink his putt on 18 to win. I can still see a dejected David Duval by the 10th tee, having been driven out on a cart to prepare for a playoff if O’Meara had missed. Earlier that week I paired up one afternoon with another student who had played college golf at Georgia Tech. We stopped in front of the clubhouse to speak to his old rival, Jim (Bones) Mackay, and I had the chance to shake hands with a player we all expected to win a green jacket at some point, Phil Mickelson. The dime store autograph book was gone, but my cherished Masters memories continued to accumulate.

The first-aid building assignment was generally a quiet day filled with occasional visits by physician members of the National who would swing by to say hello and tell a good story. On my day of duty there in 1998 I diagnosed a hernia in a caddie who had stopped in with severe pain, after which we ran over to the hospital for a quick consultation. Upon returning I stopped at the gate, where I anticipated being directed to the side road where the players parked, but the caddie suggested we drive down Magnolia Lane since his player was anxiously awaiting his return. At least that was our story. The guard — to both of our amazement — obliged. As I pressed on the gas pedal the caddie implored me to slow down. What began as an awkward moment in a first-aid tent ended with a story that would last each of us a lifetime.

But perhaps my favorite recollection from that tournament, after watching the Masters since childhood and idolizing one player in particular, was the story of what almost happened in 1998. My teammate and I had the 8th-hole assignment on Sunday, and it was difficult to ascertain exactly what was happening on the rest of the course from our vantage point, which was strategically positioned behind a large mound far beyond the green. Although our instructions had always been to minimize any personal conversations via our headsets, one member of our group was notorious for his intake of pimento cheese sandwiches. So much so that there were periodic requests for a sandwich count (reported by his rotating daily partner) from other members of our team to periodically break the long periods of radio silence. But the conversation changed and the roars began early that Sunday afternoon.

Jack Nicklaus was 58 years old and had made birdies on 6 and 7 prior to just missing a birdie at the 8th. We moaned with the rest of the patrons as his birdie putt came up short and he headed to the 9th tee. A short while later, another roar. Anonymous first aid volunteer: “What was that!?” Sandwich counts were quickly forgotten. “Nicklaus birdied 13.” Then later: “He just birdied 15!” Despite admonishments from the first-aid tent, headset decorum was now entirely out the window. Was this really happening? Could Woods win his first green jacket in 1997 and Nicklaus win his last in 1998? Unfortunately there was no fairy tale ending that day, but having witnessed the first major win by a Tiger one year earlier, it was thrilling to see the last great Masters charge of a Golden Bear the next.

* * * * *

A month later our first-aid group was back in Augusta, this time just days away from graduation and the next stage of our medical careers. Again we arrived early, playing the Par 3 twice before our tee time. Our round that day was filled with shots both great and forgettable, all of us a bit sentimental knowing this was likely to be our last round on the course. On the 18th hole my drive stopped just shy of the fairway bunker where I had gotten acquainted, ever so briefly, with Johnny Miller almost 15 years earlier. I stuck a 4-iron — easily my best shot of the day — three feet from the pin and made birdie. We squeezed in a third round on the Par 3, soaking it all in for just a few more minutes, until a Pinkerton guard said, “It’s time to go home, boys.”

After finishing residency training in Boston my wife and I returned to the Southeast in 2002, Augusta now just a two-hour drive from our home. Once again there was time for golf in my life. I wrote the chairman of Augusta National a letter shortly after moving back, reflecting on our first-aid days and thanking him for that opportunity. My man cave is adorned with enlarged canvas pictures of some of the legendary courses I’ve managed to play over the years. On a wall hangs a Masters shadow box with pictures of my tee shot on 16 from 1998, our scorecards from the rounds we played, a golf ball from the driving range (I’m not giving it back), my badge and parking pass from 1997, and a note on an Augusta National scorecard wishing me the best from Hootie Johnson.

Over the years I’ve returned to the Masters a number of times, usually with friends who have managed to hold on to badges over the years or with a lucky winner of the annual lottery. It was thrilling to watch Tiger’s miraculous chip at the 16th hole find the cup en route to his fourth green jacket in 2008, and to see Arnold Palmer hit one of his last ceremonial tee shots a few years ago. My favorite memory in recent years, however, was meeting an old friend and walking the course to absorb its splendor and recall the changes since we had last been there together. We met at the putting green that morning, had a few sandwiches during the day, marveled at the distances the players now hit the ball, and laughed about an innocent kid with his Kodak disc camera blocking Johnny Miller’s approach shot to 18. “I don’t think he birdied it that day, did he?” I asked. “No, but you did a few years later.” You’re right, Dad. I birdied 18 at Augusta National.

Rob Morgan is an anesthesiologist at Prisma Health in Greenville, S.C., with a 10.5 USGA Index (a 2-point increase thanks to a recent trip to Bandon Dunes). He is a member at Greenville CC, High Hampton, Portstewart GC, and an Ambassador at Congaree.