Loyal H. “Bud” Chapman was a brilliant artist, talented golfer and gifted storyteller. He made piles of money in commercial art and later with his Infamous 18 Golf Holes — a series of stunning watercolor fantasy holes mapped out around the globe that teased the budding course designer in all of us. When he died of a heart attack this past summer at age 97, Chapman left behind a legacy matched by few in the golf world or any world. The Minnesota native shot his age nearly 4,000 times and tried to qualify for 47 U.S. Opens, some attempts falling short in heartbreaking fashion. But that’s only a fraction of his legacy.

He was known to apply to tournaments several times (forgetting he already had) and to show up for events on the wrong week. When he was inducted into the Minnesota Golf Hall of Fame in the 1990s, he went to the wrong club for the ceremony. He used a 54-inch driver — before the USGA reduced the limit to 48 inches — and despised headcovers. Too fussy. Same with golf-bag zippers, so he always kept his pockets open; playing partners wondered how he didn’t lose more of his stuff. He scribbled swing tips in the leftover white space of his scorecards in handwriting that resembled hieroglyphics. (“I’m just trying to find the secret,” he’d say.) Calling him messy might be too kind. He kept bank statements and receipts and scorecards in grocery bags, and his son had to tear his dad’s Florida home apart looking for his last will and testament. He finally found it in a bent folder in a canvas bag that was sitting at the bottom of a tall laundry basket buried under dozens of golf magazines and bags. The folder read: “Important document. Don’t throw away.”

He was a kid at heart, really, a 97-year-old with candy bars left in his golf bag. He once delayed a trip back home to Minnesota from his winter place in Florida because Disney World was unveiling a new ride, and he had to check it out. That was just a few years ago.

“He almost had an innocence of a child,” says David Chapman, one of Bud’s four kids, along with Greg, Julie and Jennifer. “That’s how he lived life. He woke up and everything was about fun.”

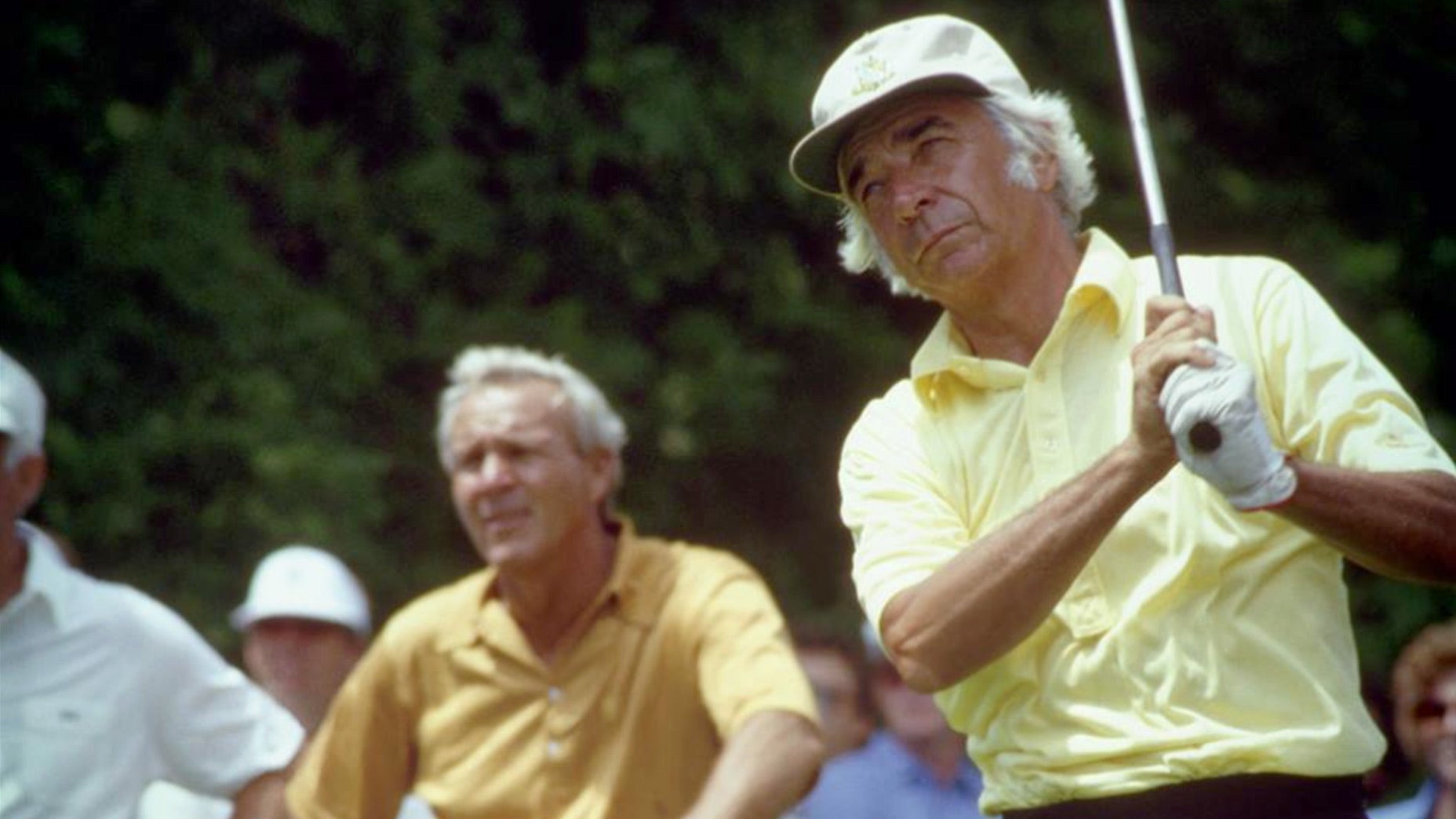

Chapman was a member at both Hazeltine National and Minneapolis Golf Club. He was a prominent figure at both, but not just because of his famous past and sharp game. He was a joy to be around. Richard Walker was one of Chapman’s regular golf partners over the past decade. He still remembers the first time they met. Bud smiled, held out his hand and looked him in the eye.

“The way he greeted people was incredible,” says Walker. “It was as if he knew them, and with compassion. He’d talk to anyone, whether he knew them or not, and when they walked away, they were better for it because he made people feel good, just for the warmth of who he was. And that was the incredible thing about him. Not his paintings or his golfing ability, but the way he made others feel. He had time for people.”

Chapman was born in Minneapolis on January 27, 1923. He grew up painting with his mother, and he was a wizard with a brush. But he had other loves, too. He started caddying at posh Interlachen Country Club — where Bobby Jones won the third leg of the grand slam in 1930 — when he was 12 years old, often grabbing the bag for legendary women’s player Patty Berg for 75 cents a loop (plus tip).

After serving in World War II, he enrolled at Walker Art School in Minneapolis. He opened his own studio and had much success as a commercial artist — his paintings were so perfect they were mistaken for photos. He mastered transparency retouching at a time when few even knew how to do it. He was commissioned from all over the U.S., including major markets like New York City and Chicago. There are stories of Chapman bringing in completed work to art directors, only to be greeted by competitors, some of whom turned down the project because they said it couldn’t be done. They had to see how he did it.

The money was good. But adventure tempted. Chapman met a prospector in the early 1970s and heard about all the gold and silver ensconced in the New Mexico mountains. He couldn’t pass on the opportunity.

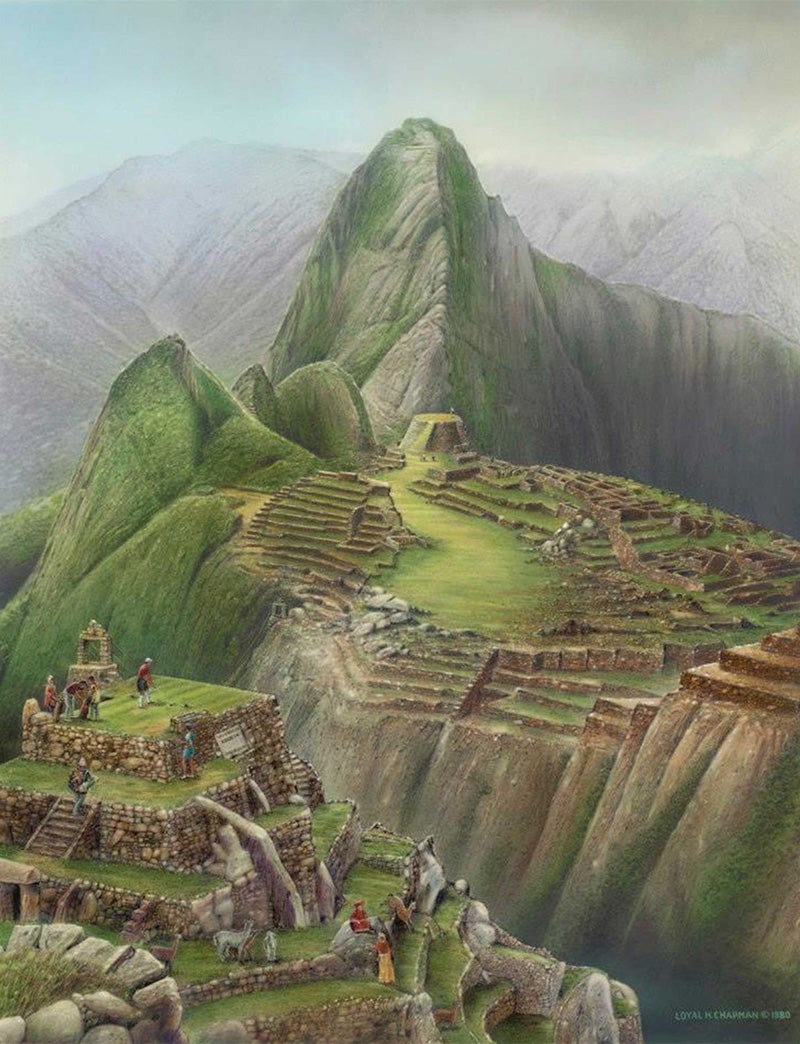

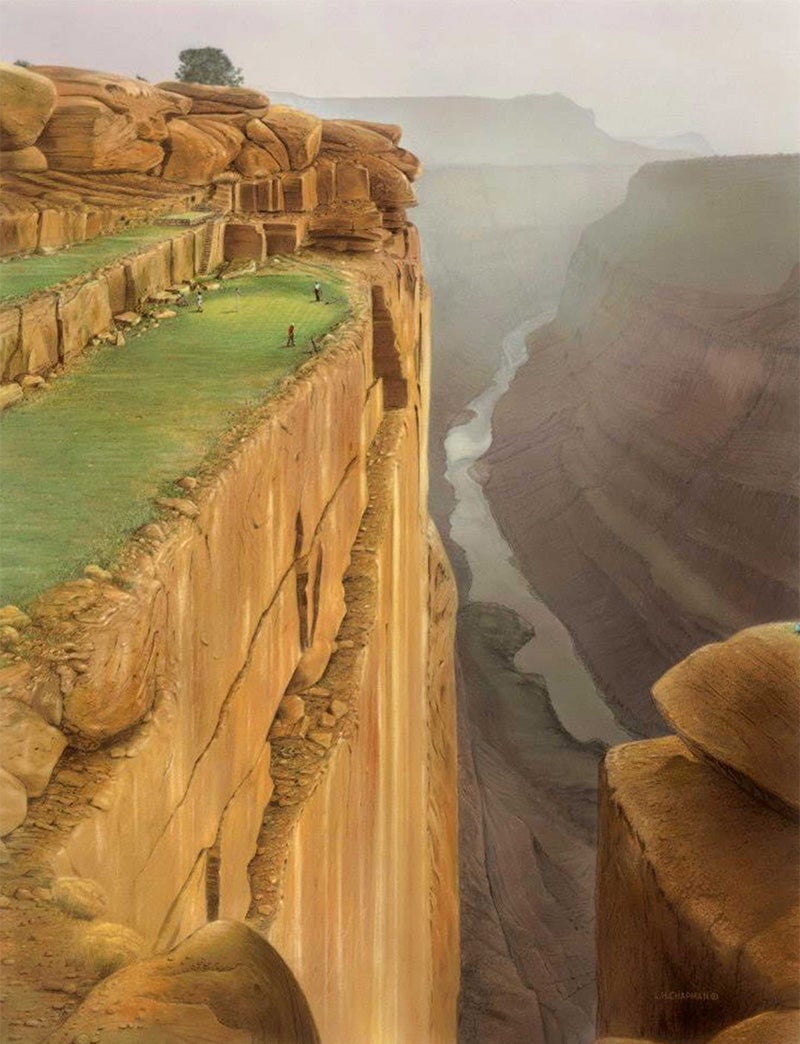

“I had to go and join him and see what I could do, but I went completely bust on it, lost everything, and I had to find another grubstake to make some more money,” Chapman said in a 2014 interview. “As soon as I said that, an explosion hit me, and I said, why not paint golf holes, infamous golf holes, and put them in the best places in the world, and make them so difficult people won’t know if they are real or not.”

The whole Chapman crew — Bud and his wife, Mitzi, raised their family in St. Louis Park, Minn. — pitched in with the newest venture. “His plan was to get us all in business so he could play more golf,” says Greg, only half-joking. “And it worked.” David credits his dad’s trips to New Mexico as inspiration for his Infamous 18 Golf Holes. He believes the stunning vistas and breathtaking topography of the southwest — mixed with his dad’s love for National Geographic and golf — led to him visualizing all of those fantastical holes.

Chapman finished his first painting, Victoria Falls Golf Club, in 1972, and he sent his first four to Golf Digest. Instead of asking for payment he requested a free ad — and business boomed. “The first couple of years was gangbusters,” David says. They hired help, got a warehouse and still continued with the commercial art business. Chapman completed the Infamous 18 Golf Holes in 1982, and they drew attention from other national publications, including Reader’s Digest, GOLF and others. To this day, his work is featured prominently in clubhouses, locker rooms, offices, in books, calendars and more. Some collectors want individual holes and others buy sets or the complete collection. Around a half million have been sold overall.

Chapman is believed to have painted more than 50 dream golf holes altogether, some of which were commissioned. He was the ideal artist for these projects because he was just as good with a golf club as he was with a paintbrush. He had an intense knowledge, appreciation and love for both. According to David, his father shot his age 3,899 times, the first when he was 68. (Bud kept track.) But that’s selling the feat short: He actually shot well below his age thousands of times.

He won the Minnesota Senior Amateur twice and the Minnesota Senior Open once, was named the Minnesota Golf Association’s Senior Player of the Year in three different decades and is in numerous halls of fame. In 1983 he qualified for the U.S. Senior Open at Hazeltine at age 60, and through 15 holes he was the tournament leader at two under. The 16th is Hazeltine’s signature hole — a par-4 with a forced carry off the tee, a creek left, Hazeltine Lake right and a narrow green awaiting — and Greg, who often caddied for his father, talked his dad into hitting a 3-wood off the tee. Bud had been pushing his driver right most of the day. Bud complied, hit 3-wood and pulled it into the creek, making double. “He blew his lead pretty fast, and I never heard the end of it,” Greg says. “He played it the next day, hit driver and made birdie.” (Billy Casper ended up winning in a playoff against Rod Funseth.)

Qualifying for the U.S. Open became Chapman’s white whale, although he didn’t start the pursuit until he was in his 40s. He was featured during a U.S. Open broadcast in 2005. That year he was 82, the oldest of some 9,000 entrants vying for a spot at Pinehurst; he carried his own bag on a cold and rainy day and shot 86, missing out by 14. He did twice advance through local qualifying to sectionals. One year, in Chicago, he needed to play the last two holes in even par to qualify, but he doubled the 17th. Another close call came in Detroit.

“I was four or five shots ahead of Sam Snead and Frank Stranahan in the last round with two holes to play when I got to a par-4,” Chapman told Sports Illustrated in a 1998 profile. “I drove the darn thing in the morning round, and I’m getting ready to hit when the caddie says, ‘Mr. Chapman, you’ve got it made. Just take an iron.’ I thanked him because it was the right thing to do. So I pulled out a 2-iron and hit it straight into the worst garbage you could imagine.

“I’m still okay,” he continued. “All I need is a double or triple on the last hole to qualify because I had that lead. It was a par-3, and jeez, I hit this 6-iron, and I thought it was going in the hole. It embedded in the bank in front of the green, but not too bad, and the pin was only about 10 feet away. The embedded ball rule wasn’t invented yet, so I go up there and just tap the ball to get it out — and it goes in a little deeper. So I tap it again, and it goes in deeper. [Laughs] Now it’s starting to get serious. I did that four or five times, and finally I closed the blade like a sand shot and exploded it out to about 40 feet. From there I four-putted and missed qualifying by one.”

He added, playfully: “I have a tendency to choke.”

Stories of Chapman’s adventures have been well-documented. Everyone has their favorite. Some are so perfect they are hard to believe — details fuzzy or a prisoner of time — but there are bits of truth everywhere.

There was that time when Chapman was an Army pilot in World War II and flew B-29s, but never went overseas. The war ended with him on the airstrip in Tucson, Ariz., ready to take off for a mission. Yet there were rumors the generals were reluctant to send him in the first place. One day he was called into a superior’s office and thought he was about to catch an earful — he always had trouble keeping his bed tidy — but the colonel had other things on his mind. “Bud, I hear you got your golf clubs with you and that you are a pretty good player?” he asked. Turns out, the brass didn’t want to lose a great golf partner.

There was that time when Chapman beat an 18-year-old Tiger Woods in a long-drive contest at the 1994 Porter Cup, a top amateur event. Although Woods hit it a touch farther than Bud’s low piercing drive that cut through the high winds, Woods didn’t find the fairway. So, technically, Bud beat him, as he liked to say.

There was that time when Chapman finally took on his own creation, when he first played the Infamous 18 Golf Holes on a simulator. It was a small get together in an office, and he basically shut the place down. After several attempts trying to conquer his own design he finally quipped, “You know, I have to tell you, this golf course is too hard to play.”

There was that time when Chapman attended his first Masters, in 2016, with Walker and another one of his golf buddies. The group was crossing the fairway on the par-5 15th when Bud suddenly slowed down. Few dared to linger in the fairways of Augusta National, but Chapman had other plans. He stopped in the middle and started taking slow, methodical swings toward the green. Eventually, he turned to his friends and said, “I’m not sure I could stop the ball on the green from here.”

“He was always in his own world, in the best way possible,” Walker says. “He had just a creative mind, but he’d let people into it.”

Chapman’s final round was on March 20 at Seminole Lake, a semi-private club with wide fairways and water everywhere in Seminole, Fla., where Chapman was a regular in Tuesday and Thursday men’s games, usually for $20. He shot 89.

Three days after their father’s death, David, Greg and two friends went to Brookview Golf Course in the Twin Cities. They all used Bud’s Ping G400 with the full-length Code Blue 48-inch shaft (no headcover) off the 1st tee. Everyone striped their in-memoriam blasts down the center, except for David. He pulled his left and made double bogey. That’s golf: perfect game, impossible to perfect. Bud Chapman knew that.