Eighty-seven years ago this month, in a tumbledown shack in Adairville, Ky., a plum-cheeked child was born, an angelic infant of heart-aching innocence.

So much for first impressions.

That child grew up to be Walter (Puggy) Pearson, among the most egregious golf cheats of all time. In a long and notorious life, Pearson was best known as a sharp-toothed card shark, but his skill set carried over nicely to the course. A latecomer to the game, he jerry-rigged a respectable swing while mastering the underhanded fundamentals of the foot-wedge and the surreptitious drop.

Not that he worried about getting caught.

One difference between Puggy and countless other fraudsters is that he owned up willingly to his transgressions.

NEWSLETTERS: Sign up for latest golf news, tips and insider analysis

“Sorry, I couldn’t help myself,” was his famous explanation for a flagrant violation he committed in a big-money match against a drug kingpin that he’d been winning handily but was forced to forfeit.

Another difference was how he was received. Far from being banished by his golf cohorts, Pearson was embraced as an outlandish character, his opponents less begrudging than bemused. Pearson’s shady play was seen as Puggy being Puggy.

Someone was always willing to take him on, with the chuckling understanding that the only hope a golfer had of beating him was to beat him to his ball.

Pearson died in 2006, yet with every passing year, he stands out all the more in a game whose unforgiving attitude toward itself is practically the stuff of a Nathaniel Hawthorne novel.

Never mind due process, hard evidence, confessions. Unlike other sports, where a pitcher who scuffs balls or a lineman who holds jerseys can pass as crafty, golf makes no allowances. It applies the “c” in cheater like a scarlet letter. To be accused is to be condemned.

Anyone who doubts this might spend some time sifting through the history of judgments in golf’s harsh court of public opinion. There you come upon the case of the World vs. Vijay Singh, who still bridles at questions (because people still raise them) over cheating allegations that date more than 30 years. The Asian tour slapped Singh with a two-year suspension, so he served his time. But in the eyes of some, his sentence might never end.

In those same dusty archives, you also find a dossier devoted to Jane Blalock, the Hester Prynne of the women’s game. In a nearly 20–year career, Blalock won 27 LPGA Tour events, including the inaugural Dinah Shore (before it was designated as a major), yet her legacy of triumph is entangled with charges that she improperly marked her ball and tamped down spike marks during the 1972 season. A player petition led to her suspension, which Blalock fought successfully. In 1974, she notched another legal victory when a court ruled that the LPGA was in violation of antitrust regulations. The following year, Blalock’s suit against the tour was settled, so officially, at least, the black mark is long gone.

But good luck erasing the memories, to say nothing of the Wikipedia page.

The larger the stakes, of course, the weightier a charge of impropriety becomes (and the greater the chance that attorneys get involved). But you don’t have to look to the game’s highest reaches to see how the c-word casts a pall. Is there any victory in sports more pyrrhic than a first-place finish in a handicapped event? Listen to the grumbling around the grill room as the suspected sandbagger claims his prize.

In most cases, that grousing never gives rise to open accusation. Golfers understand that public charges are the nuclear option; few want the brinkmanship to trigger a kaboom.

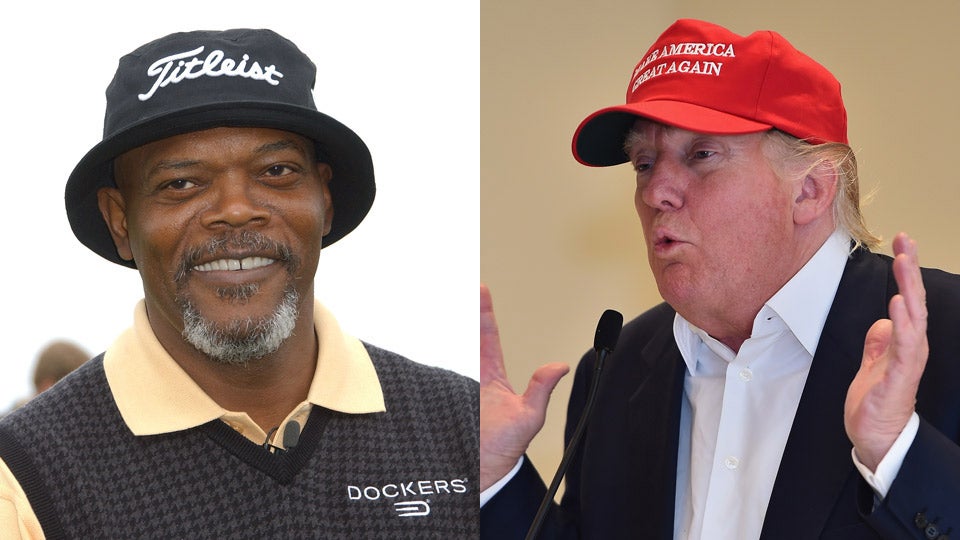

When a bomb does drop, even the sturdiest are staggered by its fallout. Witness the war of words that broke out this month after Samuel L. Jackson labeled Donald Trump as a golfer shy on scruples. A veteran of innumerable scorched-earth battles, Trump has soldiered through all sorts of explosions. But this charge seemed to wound him. By Trumpian standards, his counter-attack was muted, awkward. After first claiming, unconvincingly, that he had no recollection of playing golf with Jackson, he followed with a tweet that seemed to concede that he did. The Donald closed with a feeble: “I don’t cheat at golf but @SamuelLJackson cheats . . .”

Pearson would have had something snappier to say.

Then again, Puggy was an aberration, an unrepentant scofflaw in a game that otherwise has little love for heels.

A year before his death, I interviewed him for a story on his life on the wrong side of the rule book. His health was failing. He was short of breath. But he perked up while reflecting on his fondness for infractions.

When I asked him if he worried about how others perceived him, Puggy laughed so hard he started wheezing.

Reputation?

“Son,” he said, “I don’t have one.”

Golf could go a little easier on those who do.