The Bandon Dunes of muni golf? A course operator sees that in San Francisco’s future

The Bandon Dunes of muni golf? A course operator sees that in San Francisco’s future

Course Rater Confidential: Discussing Pete Dye’s legacy and his most underrated courses

GOLF’s Top 100 course panelists are among the most respected and well-traveled course evaluators in the game. They’re also keen to share their opinions. In this GOLF.com series, we’ll unlock their unvarnished views on all questions course-related. The goal is not only to entertain you but also to give you a better understanding of how to understand and appreciate golf course architecture. You can see GOLF’s latest Top 100 Courses in the World ranking here, and meet all of our Top 100 panelists here.

Pete Dye, one of the most influential architects of the 20th century, died last week at 94. What will be Dye’s most lasting legacy?

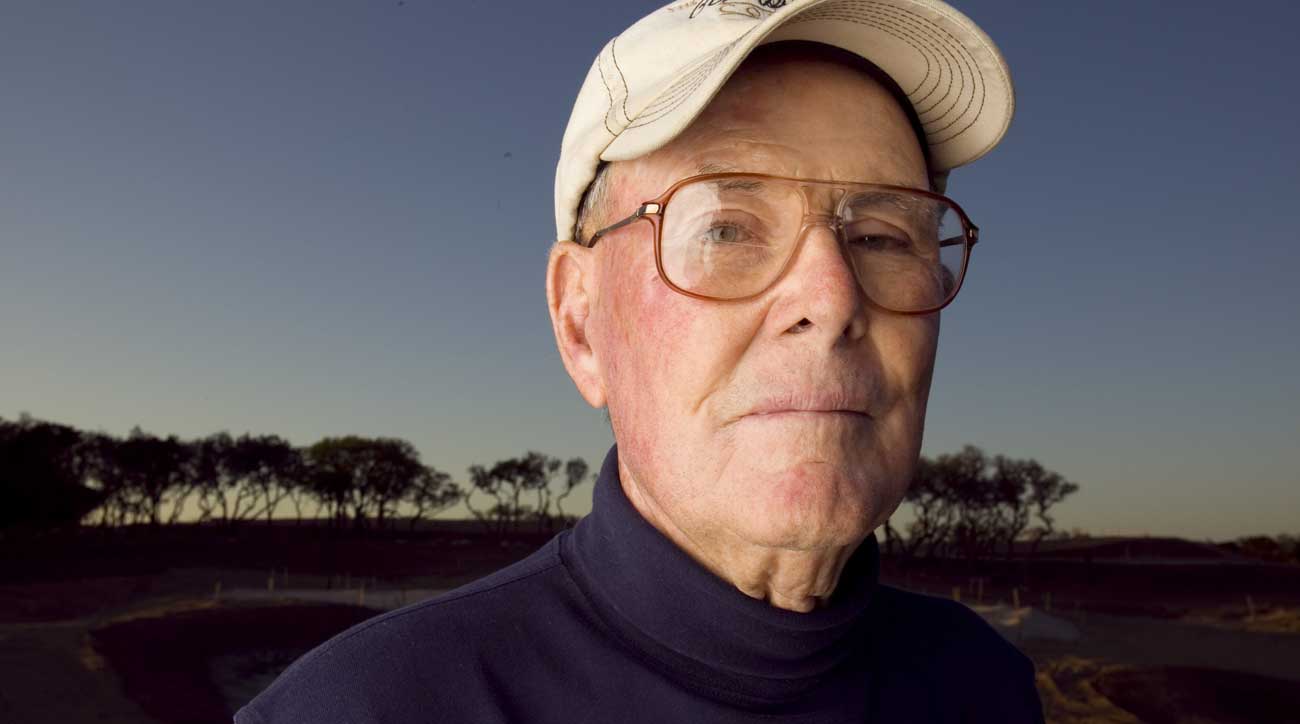

Thomas Brown (Panelist since 2015; has played 95 of the Top 100): Pete Dye’s primary legacy will be as a builder of tournament venues designed to challenge professional golfers. In the 1980s, this was best characterized by PGA Tour players petitioning commissioner Deane Beman to remove PGA West from the Tour’s annual stop in the Coachella Valley. A secondary legacy, more important to golf architecture students, was Dye’s mentorship of the next generation in design, namely Bill Coore, Brian Curley, Tom Doak, Jim Urbina, Bobby Weed and many others. Even Jack Nicklaus’ first effort in golf architecture was in conjunction with Dye, building Harbour Town on Hilton Head Island. In 2001, Dye identified technology improvements in the equipment as the source for the longer professional game. (Subsequently, GOLF columnist Alan Shipnuck recognized the upcoming reality of a 9,000-yard tournament course.) Let’s hope the next Pete Dye to come along will be allowed to prioritize skill over the chase to tame distance.

Steve Lapper (Panelist since 2009; has played 84 of the Top 100): Pete Dye was a generational disruptor, artist and mentor. He was a shrewdly confident man who changed the canvas of golf course design in a natural hell-be-damned style. His distinctive style evolved over time yet never wavered from being original and demanding. Some will write about his overt challenge to the PGA Tour, and they are right. Amateurs like us might curse and seethe at the shot-making demands, but we were never indifferent to, or bored by, Pete’s work. The legacy of the Dye design style remains as iconic as he was.

Brian Curley (Panelist since 2011; has played 65 of the Top 100): In time Pete will be known for creating two kinds of courses: those he was “involved with” (with his family; with other architects, such as Lee and I and others, where the “Pete Dye look “was employed), and those where he was all-in and, in effect, moved to the site, ran the crews, and built a course not from plans but from the ground up. These courses represent a smaller percentage of what is considered his portfolio but represent an astounding batting average for high quality courses that have endured. And endure they will. At some point perhaps the pendulum swings back from a preference for natural designs to courses that are more engineered but require more of the better player. Early in Pete’s career he opted to sway away from the big, bold, parkland bowling alley courses of the day and create ones that brought visual intimidation, angles of attack, linear hazards, rolls, bumps, grass hollows and small greens. Along the way, he created a wave of impersonators. Nobody got more out of less-than-stellar sites than Pete. But what I remember most about Pete was not so much the designs, but his quirky, humble, self-deprecating delivery that was so endearing and allowed him to sell his ideas so well (remember he was a successful insurance salesman prior to his design life). I loved spending time with him as he was 100-percent genuine and a hoot, always entertaining. Site visits with the big names are usually stiff and awkward, but Pete’s were always loose, organic and filled with creative energy. That is the legacy that those who worked with him bring to the table and have used to go on to create numerous courses of critical acclaim. They may not “look” like a Dye design but they do in fact incorporate many of the concepts he pushed and the team that builds them works from this attitude. The results show.

Jim Urbina (Panelist since 2015; has played 69 of the Top 100): Pete’s enduring legacy is the way he built his courses because he did them in the field without plans. That was a departure from the likes of Robert Trent Jones, Art Hills, Tom Fazio and others, who all built their courses with plans. They made site visits, of course, but Pete actually moved to the site and created from the ground up. I remember once, in 1988, we were working on the Arizona State University Course, and a young assistant came up to Pete with plans. He said, ‘Son, we won’t be needing those.’ As Pete liked to say, ‘We’re not course architects, we’re builders.’ That means you build there, on the site. I should add that Pete also recognized early on how far the top players were hitting it, and he designed accordingly. At the ASU course, the 16th hole was a par-3 that could play as long as 260 yards. The ASU team had a number of great players, including Phil Mickelson. I remember their coach, Steve Lloyd, telling them: none of you better aim for that green. You lay up, chip on and get your par.

ADVERTISEMENT

When golf fans think of Pete Dye, they tend to think of such well-known courses as TPC Sawgrass, the Ocean Course at Kiawah, Whistling Straits and Teeth of the Dog. But Dye designed more than 100 courses. In your view, what is his most underrated?

Lapper: This is a tough one. Little about Pete Dye was ever underrated. Although only re-constructed (hands-on, all-in) from an original Donald Ross, the elegant and understated Gulfstream Golf Club is an under-the-radar work by Pete and Alice. Though hardly emblematic of their usual diabolical — and often excessively penal design — a distinct Dye footprint was left on this sublime seaside lawn.

Brown: Waterwood National, north of Houston, has my vote as Dye’s most underrated. Long before Ben Crenshaw or Dick Youngscap, Bill Coore trained under Pete Dye, helping build Waterwood National and then graduating to become Waterwood’s superintendent. Coore was on site for six years. Sadly, the golf course closed to the public in 2009.

Curley: I suppose it would be, for me, The La Quinta Hotel Mountain Course. Built largely within a huge basin and up against the toe of the slope of the Santa Rosa mountains, it is a core course in the world of condo-lined courses of the Coachella Valley and is a great introduction to the Pete Dye playbook. It is overshadowed by the nearby Stadium Course at PGA West but is pure golf. Stark, intimidating, full of angles and a bit rough around the edges (at least it used to be). Not your typical palm-tree lined, waterfall spectacular seen in so many other area courses.

Freeman: The Golf Club, in Ohio. Terrific routing that is known to cognoscenti but under-appreciated as a whole. The land, though flat, presented Pete with a chance to make his most classic looking (in a golden age form) course I’ve seen of his. A masterful job of hole shapes, lengths and slippery putting surfaces. Oh, and he did throw in some railroad ties in spots. It should be more widely known.

Urbina: I’d like to call out three. The Citrus Course in Palm Springs, Firethorn in Nebraska, and Old Marsh in Florida. The Citrus Course came in the wake of PGA West and is overshadowed by that course, but it shows the wonderful creativity and variety of Pete’s work and the beauty that comes from building from the ground up. Old March has an impressive amount of coastal frontage and Pete took full advantage but he did so without the holes ever feeling repetitious. Firethorn is on rolling farmland south of Lincoln, and Pete really maximized the site. He had some template holes himself, and if you’re looking, you can see them at Firethorn. Pete built Firethorn for Dick Youngscap, who went on to build Sand Hills with Bill Coore. Coore, of course, had worked and learned under Dye. Another example of how Pete’s legacy extends on and on.

To receive GOLF’s all-new newsletters, subscribe for free here.

ADVERTISEMENT