Developing Tom Doak: Prolific and opinionated, the famed architect remains a work in progress

Tom Doak surveys the gone-to-seed High Pointe, his solo debut.

Josh Sens

It’s a blazing afternoon in Northern Michigan, and the architect Tom Doak is tramping across prickly underbrush on a walk that doubles as a trip down memory lane. The terrain is wooded, but, as Doak treads on, the trees give way to a rumpled clearing: the corridor of an overgrown par 4.

“This used to be the 10th hole,” Doak says.

More than 30 years have passed since Doak first set foot on this rolling property outside his adoptive home of Traverse City while devising plans for High Pointe Golf Club, his first solo design. The course received raves upon its 1989 opening and enjoyed a stint on GOLF’s Top 100 in the U.S. list, only to shutter in the wake of the 2008 economic crash.

For years, Doak had little reason to revisit the grounds. But in recent months, he’s been back often. With new investors behind it, there is now the prospect that High Pointe will be revived, and Doak is on board for the job.

That Doak has returned to where it all began seems fitting. He was hired to build High Pointe when he was 26, an unabashedly opinionated up-and-comer better known for his writings than for his routings. He is 61 today and a giant in his field — an éminence grise still tinged by his youthful reputation as architecture’s enfant terrible. To Doak, the lingering image is a frustrating distraction, kept alive by golf writers who produce stories about personalities — like Doak — “because it’s easier than talking about design.”

Frank talk about design was what Doak provided in The Confidential Guide to Golf Courses, a now-seminal survey that he penned in 1988 as a kind of trip planner for golf-loving friends before selling revised copies to a larger audience. In capsule reviews and 0-to-10 ratings of upward of 900 courses, Doak was bountiful in praise for a range of designers and their courses, but what stuck with many readers were the unflinching critiques. “I came away convinced [Desmond Muirhead] is having LSD flashbacks” — Doak’s assessment of Stone Harbor in New Jersey, a Muirhead project that Doak described as “the most ridiculous course I’ve ever seen” — was emblematic of his knack for cutting to the quick.

In architecture circles, people didn’t so much quarrel with Doak’s opinions as they did with his choice to broadcast them. If you’ve got nothing nice to say was a professional code, and Doak had broken it. In his honesty, though, he became a leading voice in a transformational movement.

The minimalist views that Doak espoused are now the guiding aesthetic in modern design. And Doak, once deemed a radical, is now an establishment figure, a face on course design’s Mount Rushmore. His courses — from Pacific Dunes in Oregon to St. Patrick’s in Ireland to Tara Iti in New Zealand and beyond — proliferate on Top 100 lists. Designs by others, who have either worked with him or for him, including Kyle Franz and Gil Hanse, are richly represented in the rankings too.

His biggest contributions have been to show people how a trained architect looks at courses and to give people language to talk about design.

Doak may never be anointed “Mr. Popularity” by his peers, but he has plenty of admirers among them. And even those who see him as less than cuddly are quick to acknowledge his contributions. No living architect has done more to shape the conversation around design, to say nothing of the places where we play.

“All the focus on a few negative comments ignores the fact that [Doak] has had more nice things to say about more designers and their work than anyone in the business,” says GOLF’s architecture editor Ran Morrissett. “His biggest contributions have been to show people how a trained architect looks at courses and to give people language to talk about design.”

A career in architecture became Doak’s dream around the time he learned that it could be a job. The older of two brothers, raised in Connecticut, he started playing golf in grade school at a local muni but found his deeper passion while accompanying his father, a commodities trader, on business trips. The highlights of those excursions were stops at some of the world’s most esteemed courses, including Cypress Point by Alister MacKenzie, the Golden Age icon who became Doak’s idol, and Harbour Town Golf Links by Pete Dye, the modern icon who became Doak’s mentor. Doak couldn’t get enough of great design. When one of his father’s business contacts gave him a copy of the World Atlas of Golf, a landmark 1973 compendium of photos and essays that lived up to its globe-spanning title, “I pretty much memorized the book,” he says.

A math whiz, Doak spent a year in college at MIT, where he doodled golf holes during engineering classes, before transferring to Cornell to study landscape architecture, the closest he could come to a pragmatic major, given the work he aspired to do.

“It’s hard for people to realize how invisible golf course architecture was as a profession in those days,” Doak says. “Before Jack and Arnie started getting into it, there wasn’t a lot of attention paid to who designed the course.”

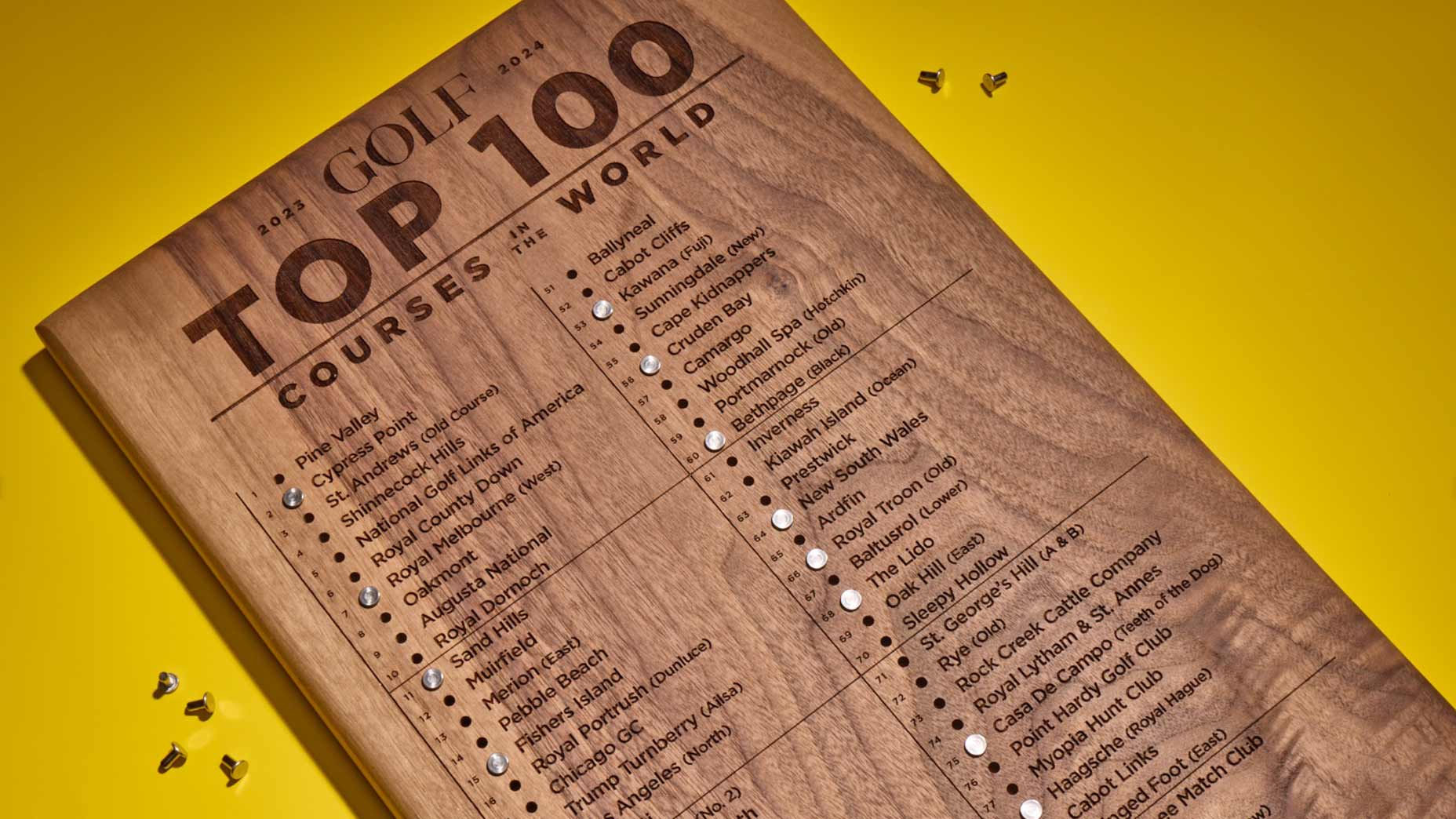

Doak was a sophomore at Cornell in 1979 when GOLF published its first-ever feature on “the 50 greatest courses in the world” — a list the magazine arrived at by asking a select group of golf buffs here and overseas to name their 10 favorite courses, and then extrapolating. The result was a hodgepodge that ranged from bucket-listers most golfers knew from television (Augusta National, Pebble Beach) to head-scratchers (Royal Hong Kong and Wack Wack in the Philippines) that you’d really seek out only if you lived nearby.

Doak dispatched a letter to the magazine, laying out his quibbles and offering suggestions for improvement. For starters, why not assemble a panel of experts and give them a ballot with hundreds of courses from which to choose?

Reading Doak’s missive, GOLF’s then-editor in chief George Peper came away with clear impressions.

“This kid knew his architecture and had strong opinions about it,” Peper says. “But more than anything, I thought, He can really write.”

Soon, Doak was channeling that talent into articles on design for GOLF, a freelance gig that led, in 1983, to an unofficial role as the magazine’s architecture editor. Doak was 23 and fresh off a scholarship year in Scotland, during which he’d caddied at St. Andrews and visited more than 170 courses. For roughly the next decade, he oversaw the biennial world rankings before stepping down to avoid potential conflicts of interest. Having apprenticed for three years under Dye, he was now building courses of his own.

If Doak’s career had evolved, so had the rankings. For one thing, the original list hadn’t really been a ranking because it hadn’t placed the 50 courses in numerical order. Now there were numbers attached to each, and the total had doubled to 100. The composition of the panel had begun to shift as well. In the ’80s, the magazine had striven for an industry cross section — top professional and amateur players, architects, photographers, bigwigs from the governing bodies. As a consequence, Doak says, “whether a course was challenging to good players was more of a factor.”

While there are still prominent figures and serious sticks on the panel today, most raters aren’t household names, and the average handicap index has risen. “So there are more 6,500-yard Seth Raynor courses on the list,” Doak says.

That’s not all there is to it. The rankings reflect a range of considerations, though GOLF has never told its raters what criteria to use. To do so would be silly, Doak says, because “people have strong opinions, and they will make those opinions win by any system.”

In the end, it’s all subjective, an obvious point that is often lost when the lists come out. Though he helped make the rankings mainstream, Doak has mixed feelings about their impact. Yes, they bring attention to design and spark healthy debate. But they can lead to unproductive fixations on differences that boil down to decimal points.

“So then you have a club that drops a few spots and receives the news in horror. ‘My God, what do we have to do?'” Doak says. “And I’m like, ‘What do you have to do? You’re the 20th-best course in the world!'”

Of his Confidential Guide, Doak says his wife, Jenny, has told him: “That would have been a really great book without the numbers.” Not that he’d want a do-over. Doak put out the original as a kind of corrective to what he saw as the rose-colored fluff of so much course-related writing.

“Everything you read was always ‘good, better or best,’” he says. “I understand why. But that’s not very helpful if you’re going to Ireland and trying to decide where to play.”

If he had his druthers, every review he wrote would have been taken in the spirit in which he says they were intended — with a focus only on architecture. A professional discussion. Nothing personal. But that’s not human nature. For most people, there is no disentangling the two.

David McLay Kidd, whose Castle Course in Scotland received a zero rating in the 2014 edition of the Confidential Guide, says he let the criticism roll off his back in part because “you can’t really hold someone accountable who isn’t really aware of his effect on others.”

“I’ve always thought of Tom as an immensely talented designer who is not as talented with people,” Kidd adds.

Doak is aware that some people feel that way about him, and he cares enough to bring the topic up himself. In an August podcast with The Golfer’s Journal, he addressed what he described as “my media reputation as an a–hole.” What followed was candid talk about Doak’s quest for greater self-understanding, including his participation in group-therapy sessions for those who grew up, as he did, in a family shadowed by alcoholism.

The podcast showed a softer, more reflective side of Doak that people close to him say is widely overlooked.

“I’ve found Tom to be an incredible individual,” says Michael Keiser, codeveloper of Sand Valley in Wisconsin, where Doak has two courses in the works. “He is very kind, positive and empathic — almost the opposite of stories I’d heard.”

It was Keiser’s father, Mike, who hired Doak to build Pacific Dunes, the brilliant 2001 design that vaulted him to next-level stardom. More than 20 years later, Doak has reached a point where he could coast. But while he has ceded ownership of his original design firm, Renaissance Golf, to his associates, in part to foster opportunities for them, he remains active. There’s an artist’s restlessness about him, drawn to out-of-the-box projects. In 2016, he cut the ribbon on the Loop in Michigan, a reversible course that made good on a concept that he’d yearned to do for decades. His works-in-progress at Sand Valley are a heathland-inspired par 68 called Sedge Valley and, across the road, the Lido, a semiprivate clone of a long-lost C.B. Macdonald masterpiece.

Once you’ve made a name, Doak says, repeating yourself is considered smart business. But he says he feels a responsibility to “use my position to advance the art.”

Even his plans at High Pointe call for breaking fresh ground. In 2015, the front nine of the abandoned course was turned into a hop farm. But new ownership has another adjacent parcel that Doak intends to use in his resurrected routing, which will feature 12 new holes. The holdovers — what were once holes 10 through 15 — comprise what GOLF’s Morrissett considers “arguably the finest six consecutive holes Doak ever built.”

On this sweltering afternoon, Doak has reached the green of one of those holes, the former 11th. The old putting surface is browned-out and scruffy, but its original shape and contouring remain. Large and rollicking, it is one of Doak’s favorites.

Standing at the back edge, beside a small bunker, he points to the tilts and tiers, the runoff areas and potential hole locations, outlining the thinking that went into the design. “It would be great to give people a chance to play this one again,” he says.

A lot has happened since they first did. Doak has built 40 more courses. He has been married, divorced, remarried and become a father to five and a grandfather to seven.

“On the personal side, I’ve changed a lot,” he says.

It’s too early to say when High Pointe may open or where it might land in the rankings. What’s certain is that it will have the designer’s hallmarks, with features at once fresh and familiar.

It will be, like Doak, both different and the same.