Houston golf guide: 6 great public-access courses near Memorial Park

Houston golf guide: 6 great public-access courses near Memorial Park

‘All aboard!’: Inside a golf safari adventure through the wildlife and raw beauty of South Africa

In Africa, the sun keeps all its appointments. And the sun has shown itself on this railway platform hours in advance of the train. It drops its light softly on the late-summer, late-morning gathering of rail passengers getting set to embark: to Pretoria toward Durban, toward the sea and the wilds of Swaziland. Nine days of railroading for them. And golf. These erstwhile passengers sip champagne to ward against the approaching heat. A violin and a cello narrate from beneath a rooftop shadow.

Soon it’s just past eleven o’clock on that morning in Pretoria. Alongside the platform at the Rovos station stands the train designated in railway guides as The Pride of Africa. It consists of a single (great, huffing) engine, the guards car, a crew car, a kitchen, a dining car, seven sleeping cars, a lounge car and an open-air observation car, which sits buckled to the train’s end where one might normally expect a caboose. It is all benches, that one.

Thirty-nine passengers, one train, powered by steam, set to rumble into the lush gut of eastern South Africa. Thirty-nine passengers on the world’s only golf safari. Perhaps it is the steam itself, breathy in its bold chuffs, or the servers, dressed in black tie, with their trays of cold lychee juice, or the roll call of names shouted by the railway’s owner, Mssr. Rovos himself, that make the whole moment feel like the dark opening scene of a Graham Greene novel. You feel like somebody’s bound to betray you, or offer a smoke, or peer at you from behind a newspaper.

When Rovos calls the name of your humble reporter, I stumble forward to board. He pronounces my name nicely and shakes my hand with the firmest assurance of the railroad magnate he is. (Perhaps the last one. Rovos has reclaimed and restored a fleet of more than a hundred early20th-century passenger cars and seven steam engines since the early ’90s).

“Chiarella,” I say.

“Salisbury,” he replies dryly.

“Sorry?”

“Salisbury,” a woman behind him calls out softly.

I’m certain there’s been some mistake, that they are mistaking me for an earl. Or, at the very least, a pretty mediocre ground steak preparation. So I declare my own last name louder; I really put an exclamation point on it. The woman, and the two attendants at her side, reassure me, urge me to step up onto the train, to turn left at the passageway and get on with the business of the journey. “Salisbury,” they say unreassuringly.

“Which room is it then?” I ask. “Are you giving me a key?”

“There are no keys,” the woman says.

“The cabins have no numbers,” says another.

“Look for the Salisbury cabin,” says the third. “That’s the one for you.”

No keys. No cabin numbers. It feels confounding. So, turn left, and just like that, step into the dark folds of train travel in decades long past. It sure isn’t today.

I’m on a golf safari, a blisteringly luxurious piece of fantasy travel offered by the Rovos Rail Company, which sends their restored Pullmans out on trips all over South Africa and up the continent as far as Tanzania. This nine-day trip features a massive 2,100-kilometer loop throughout eastern South Africa, five rounds of golf on superior courses set at distant points on the landscape, and a game drive or two in the world’s greatest national wildlife preserves. Mountains. Grasslands. Farmland. And yes, jungles. This ranging in price from $7,200 to $9,400 per person (double occupancy), plus airfare.

No televisions on the train. No radio. No Wi-Fi. No cell phone use permitted, except in your cabin. Minibar. Daily laundry service. Vitally strong air-conditioning. Every cabin has a roomy bathroom en suite. Some have bathtubs.

Coat and tie required at dinner, which turns out to be pretty cool because no matter how well you put yourself together, it’s hard to live up to the nightly four-course offering of delicately plated food—freshwater lobster, breast of ostrich, duck confit, antelope—and a four-bottle wine flight of excellent, promptly served South African wines, followed by aperitif.

There are afternoon lectures in the observation car by the cultural historian who leads the game drives and market visits, and surprisingly sharp swing analysis offered by the young South African golf professional who travels in our midst, using footage taken on the course the day prior. He’s a handsome, ruddy guy, who handles transporting the golf bags in the early morning, making them ready for the passengers’ arrival, setting the pairings, tallying the scores, providing prizes for daily competitions given at the end of lunches in the clubhouse.

The train manager, an icy-calm forty-something woman named Daphne, visits with every table each night to update the schedule, deliver the weather for the next day, news of the track condition for the night ahead, or simply to share a glass of vino now and again. Beyond that, the wine steward is aces-up. The servers, first class. Every cabin has an assigned attendant, who makes the bed, folds your clothes, provides extra blankets, and brings an orange soda and some crisps to your cabin when you need them late at night. There’s even a pretty sweet smoking lounge.

Other than that, it’s rough-trade, fend-for-yourself travel, not for the weak of heart and so forth, with the needless warnings inserted here for a measure of humor and/or modesty. No, the golf safari is a gorgeous thing, in every aspect, perhaps most of all the reassuring breadth of the humanity encountered, on the train and on the course.

The golf is strictly African, though. Regal in presentation, ambitious in design, the courses are sometimes rough in their upkeep, in need of lengthening to meet up with new technology. They seem a bit forgotten, at times. But come on. You’re in Africa. My God, elephants walk here. Giraffes. Monkeys live in the trees near the halfway houses. Maybe you don’t like the slight sidehill drift of the tee box, or greens that are gummy and a smidgen gone to seed. Africa, fool. Every day here arrives like a telegram from a time you never saw in the first place.

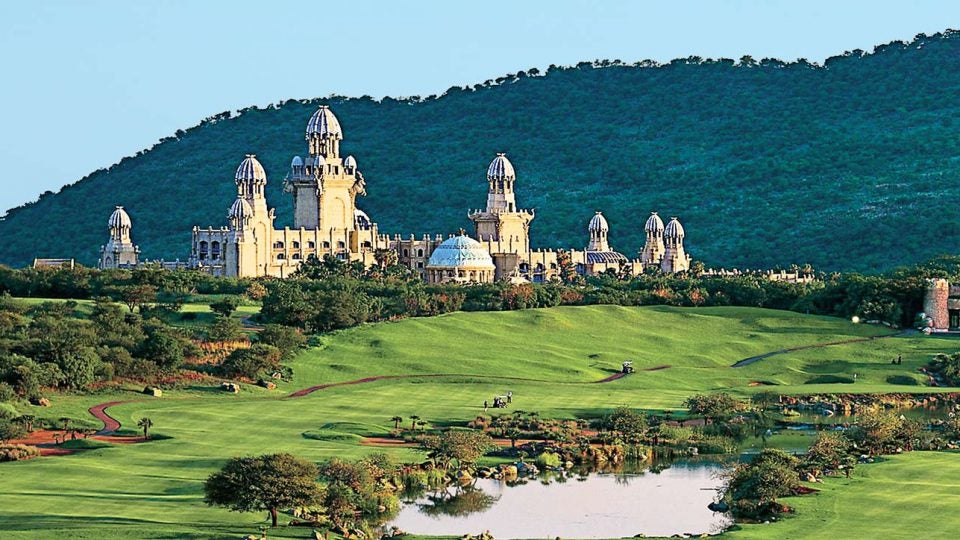

In a world where the largest warning sign on the course reads Mind Snakes in four-foot-high letters, controlling the environment feels anachronistic at best. But the mind does snake during African golf, across ancient neural pathways of fight vs. flight. At the Lost City course at the Sun City Resort, on our first day out, I stumbled upon an 18-foot crocodile curled up like a couch in the sun, not three feet of jaw-snap between him and my glossy-white ProV1. Flight, my friends. Flight.

Coming off a long flight (a direct one from the States runs as long as 16 and a half hours) and a half day’s travel by train, Lost City is a good starting point for the bleary traveler. I came out slow, stepping right off our shuttle bus and onto the first tee. Mine was the senior caddie on the course, a wiry, 65-year-old black man who kept a brisk pace and humbly begged my playing partners to stay out of the rocks while looking for balls. Early on, he convinced me to stay on the grass. “We have black mambas,” he said. “And puff adders.”

“No cobras?” I asked.

“Yes, cobras,” he snapped. “This is Africa— yes, cobras. Of course, cobras.”

He and I fell into typical conversation as he guided me through the round. He had two young children. Being a caddie is easier now than it was under apartheid, when he was routinely cuffed for giving a faulty read on a putt. He asked about my life. I gave him my hat. “Africa is made of bone,” he told me near the end. “A layer of vegetables, then soil, beneath that diamonds and metal. And coal. But then there is a skeleton.”

He seemed perfectly certain that the world sprung from bone. “Just like the Bible,” he said, as I tipped him out. “Just like the rib of the Adam.” He held up a white tee, as if it were an illustration of his point. I can’t say I know what he meant.

ADVERTISEMENT

There are 39 passengers on the train. All of them are couples. Four from the UK, six from Sweden, one from Belgium, two from the United States, one from Denmark—and me. There are five French couples, traveling together, who don’t speak English, which seems to irritate the Belgians at first. But the French keep to themselves, and I often sit with them on the back of the bus, because I can tell when they are talking about me. Turns out, they are kind.

By my tally, among the men and women are one diamond broker, one former professional volleyball player, one retired farmer from England, one staff member from the architectural program at Stanford, one supermarket owner from France, a mechanical engineer from Edinburgh, a risk manager from Sweden, a golf promoter from Sweden, one guy who claimed to have been a craps dealer, a sports writer, an insurance agent and a professor, two lawyers and a political activist. They are a symphony of impossibly musical names. Peer and Conny. Rolf and Annica. Didier and Natacha. Bo and Ulla Marie-Anne. Johan and Carine. Another Johan and Lally.

In many ways this trip is like a cruise, a journey outward with a fixed cast, friendly competitions by day, dinner seating, followed by recounting and recantings over drinks by night. But it is, in measure, far more of a physical test.

The train, for all its comforts, will get you. It sits for long periods in freight yards. Much of the transit from one city to the next occurs at night, while passengers sleep, or try to. At its best, the movement of the train is soothing, rhythmic, something like the way it looks in old movies. That’s a fierce illusion, because at its worst, the night passage is a real racket. Some nights it’s like sleeping inside a rooftop air-conditioning unit. With a bent fan blade. Soon, already jet-lagged passengers admit they are getting by on a supply of Ambien, or not sleeping at all.

When the movement of the train wakes me, I settle for sitting up alongside the window, looking into the darkness as one platinum mine or another cascades into the increasing distance. I remind myself: I’m looking at Africa, its spare streetlights, its inky-black mountains, its gaping sky with ancient stars I’ve never seen before. It’s 3:00 a.m. in Africa, I tell myself. I can be happy to look into the distance as if this world has something to do with me.

But I do not sleep.

The most surprisingly beautiful course on the trip? The Champagne Sports Resort Course, in KwaZulu-Natal, a 6,694-meter, gorgeously bunkered parkland track that grips the rolling hills in the central Drakensberg mountain range as if it were formed there. From KwaZulu-Natal, we rolled out to Durban, for a round at the Durban Country Club, which sits wedged between the city and the coastal highway. The course is heavily arbored, sculpted from sand and situated on a rise above the highway, so the ocean is what you see. At best, it’s a challenging championship course (17-time home to the South African Open Championship), and at the other extreme it’s a wonderful example of urban golf, sitting proudly beneath the mantle of Durban’s massive rugby stadium. Oddly, the course claims that its signature hole—the difficult, 464-meter, par-5 third—is rated the “best third hole” in the world. I can’t make much of that.

On the morning we are to head into Swaziland to play Royal Swazi (a rough-and-tumble, 6,166- meter layout nestled inside the tiny nation), my friend John Boyd, the British farmer, tells me I turned in a bit too early the night before. Missed some real excitement. “My wife and I had a bit of a row with another British couple over Brexit,” he says.

In that moment, it occurs to me that I haven’t heard a single word about the American president in more than five days. Another blessing of this train. John is still aghast. “They are full-blown Departers, it turns out. And they claimed a rise in knife crime was due to the influx of Romanians! What nonsense! Naturally, Linda wasn’t having that. We employed hundreds of Romanians in our fruit business. Without exception, they were educated, motivated workers. And taxpayers, Tom.”

I offer my sympathy. Later, I check in with the Departers. “People are so afraid of different ideas,” the husband says to me at that evening’s black-tie party. (We are supposed to be dressed like Gatsby. He’s wearing a golf shirt, pinched around his neck with a multicolored bow tie.) “You can’t ever get away from home, can you?”

But you can. Eight days in, we end the golf at Leopard Creek, where the greens suddenly run true on the toughest-to-get-on course of our journey. It’s a 1996 Gary Player track— consider by many the finest course in all of South Africa—lovingly renovated by his close friend Jack Nicklaus many years later. Besides some particular rules about black socks (verboten), the course is an open though difficult test of golf for your sleepless correspondent. This is our “championship day,” and fine farmer John Boyd is leading my team.

At one point, he sneaks ahead to a fence by a river, a vantage point looking down into Kruger National Park. I’m fussing over my putt, thinking a 12-footer might put the fix on a lousy round. John waves hard for me to join him at the river’s edge. “You must see this, Tom!” he calls.

Thirty feet below us stand two hippos, up to their necks in the swiftly-running brown water. They are slick and, in my memory now, somehow pink—and they appear to be, for lack of a better word, frolicking. It’s the only word I can think of to describe their half leaps and head tilts. I have had dogs, wonderful best-friend kind of dogs, who could not express their happiness this well.

I find myself speechless—the hippos, the river, the grassland, the distance. The happiness out here. John had told me he didn’t care for animals, so I don’t allow him to see that I have tears in my eyes. True! What a sap. Over two hippos. And their baby—the size of a large pig, standing in the shallows.

I find myself speechless—the hippos, the river, the grassland, the distance. The happiness out here. John had told me he didn’t care for animals, so I don’t allow him to see that I have tears in my eyes. True! What a sap. Over two hippos. And their baby—the size of a large pig, standing in the shallows.

To receive GOLF’s all-new newsletters, subscribe for free here.

ADVERTISEMENT