How do we measure greatness in sport?

No one would dispute, for example, the monumental achievement of Roger Bannister’s sub-four-minute mile in 1954. Or Don Larsen’s perfect game in the 1956 World Series. Or Bob Beamon’s propulsive, world record–shattering leap—29 feet 2½ inches—in winning the long jump gold medal at the 1968 Summer Olympics. What Bannister, Larsen and Beamon accomplished were moments of greatness, and certainly, those moments endure. But a more convincing measure of athletic dominance is stringing together solid performances—steady good play that becomes great play. In a word: consistency. Or, a streak. These are the sports feats of our imagination, the standards of greatness that inspire our ultimate respect and awe.

Still, even the most celebrated of these accomplishments have been challenged by other, almost equally magnificent jocks. In hockey, Wayne Gretzky holds the longest consecutive point streak (scoring a goal or making an assist) at 51 games. Mario Lemieux neared the Great One’s coup, with points in 46 straight games. In football, Drew Brees threw touchdown passes in 54 games in a row; with 52, Tom Brady was just behind. In tennis, Martina Navratilova won 74 consecutive matches, while Steffi Graf walked away the winner in 66. In each of these formidable records, the distance between the top achiever and his or her closest competitor isn’t all that great; the feat has been aggressively, if not ultimately, challenged. After all, records—even these—are meant to be broken. But there is one record streak that might be the sports triumph for the ages. And it does not belong to a guy named DiMaggio.

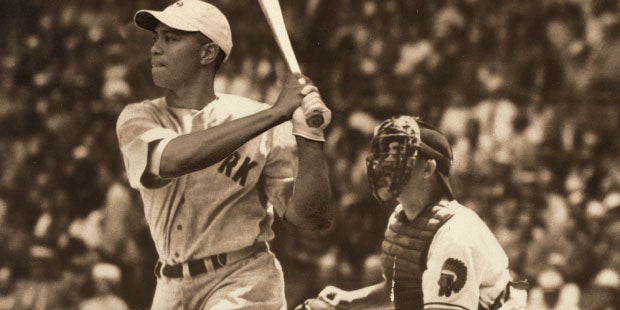

Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak in 1941 is regarded by many as the greatest individual feat in all of sport. Volumes have been written about its unreachable heights, its once-in-a-lifetime happenstance. It is considered the ne plus ultra of stats.

As a passionate fan of golf and analytics, I was struck by the paucity of documented records and streaks in golf, especially compared with other sports. Thanks to the PGA Tour’s wealth of scoring data, which dates back to 1983, I was able to do some digging—a lot of digging. (There have been about 1,500 Tour events played since 1983.) The stats yield all kinds of fascinating streaks and records (see pages 94-96). Discovering a streak of DiMaggio-esque significance was the last thing on my mind. Yet, out of the blue, there it was.

As records go, golf’s longest beat-the-field streak may not sound as sexy as the Yankee Clipper’s historic achievement, but it’s almost certainly as astonishing in its dimension—maybe more so. A beat-the-field streak is the number of consecutive rounds in which a player’s score is better than the average score of the field for that round. For example, if a player shoots 69 when the field average is 70.8, the player has “beaten the field.” A Tour player stringing together a long run of fine rounds would be a great measure of dominance and consistency.

Considering all players at all PGA Tour events since 1983, what would you conjecture is the record for the longest number of consecutive rounds beating the field? I put the question to dozens of golfers, fans, and Tour professionals, and their estimates ranged from 15 to about 35 rounds. Those rough guesses would be spot-on, were the sport limited to mere mortals. For example, Mark O’Meara has the second-longest beat-the-field streak, with an impressive 33 consecutive rounds in 1992. When I made O’Meara aware of his feat, he was surprised. “That’s an interesting stat,” he said, “and one I take pride in.” Peter Jacobsen ranks fourth on the list, with 30 straight rounds beating the field. Again, impressive. Of all the people I asked about the streak, Jacobsen, by far, made the loftiest guess. “Tiger could have some crazy number,” he said. “It could be in the 60s.” Jacobsen is right in two respects: the record-setting number belongs to Tiger Woods, and it’s crazy. Crazier than crazy.

[pagebreak]

From August 1999 through November 2000, Woods beat the field’s average score in an astounding 89 consecutive PGA Tour tournament rounds. That is roughly three times the length of the streak posted by his nearest competitor. (Only official PGA Tour stroke-play events are counted for this streak, so the WGC-Match Play, for example, is not included.)

O’Meara, Stewart Cink, and Jacobsen—numbers 2, 3, and 4 on the all-time list of beat-the-field streaks—had exactly the same one-word response when I told them of Woods’s staggering stat: “Wow!”

Why is a beat-the-field streak significant? First and foremost, it identifies consistent good play—above-average performance in round after round, tournament after tournament. The two most similar streaks are consecutive sub-par rounds and consecutive cuts made, but they don’t remotely stack up. Consecutive sub-par rounds uses the inferior benchmark of par, which is not a reliable measuring stick. The all-time leader on Tour in consecutive sub-par rounds is Jeff Sluman with 23, in 1996. Most of those rounds were shot in lesser competitions like the Greater Milwaukee Open, where Sluman broke par each day but finished the tournament in a tie for 34th. His 70 in round 3 was one better than par but 1.7 strokes worse than the field average of 68.3. In that “magical” year for Sluman, he went winless and finished 28th on the money list.

Compared with beating the field, consecutive made cuts—a record also held by Woods, at 142—is a markedly more modest feat because it doesn’t require consistency round after round. You could post a quality score on Thursday, a poor score on Friday to barely make the cut, then tank on the weekend and still extend a consecutive-cuts streak. Significantly, a beat-the-field streak demands playing well every round and against a tougher field on Saturday and Sunday.

How hard is it to maintain this kind of streak? Harder than winning! It’s possible for a player to win a tournament and not beat the field in all four rounds. Stewark Cink, third on the list with 32 consecutive rounds beating the field in 2004, describes the difficulty this way: “The field never has a bad day. There’s almost always some factor that could come up and get you, even if you play well.” Referring to Woods’s streak of 89 straight, Cink says, “That’s a lot of rounds in a row without a major catastrophe derailing you.”

[pagebreak]

Let’s see how Tiger did it. It started in August 1999 at the WGC-NEC Invitational at Firestone. After an opening-round 66 gave him a one-stroke lead (and beat the field average of 70.3 by 4.3 strokes), his second round 71 was 0.8 strokes worse than the field average of 70.2. That stumble would be the last round in more than a year in which the field beat Woods. Tiger’s streak for the ages began that Saturday, when he blitzed his competitors with a score of 62 against the field average of 69.6. His closing 71 beat the field by 1.7 strokes and sealed his victory.

Woods’s 1999 triumph at Firestone was the first of six consecutive wins and sparked a beat-the-field streak that spanned 24 tournaments and included three major wins, 13 total wins, 21 top 10s, and $12.5 million in prize money.

Every great streak has its close calls, and Woods’s was almost derailed at his very next tournament, the Disney. He was tied for the lead after three rounds of 66, each day comfortably beating the field. His closing 73 was enough to win the tournament, but it barely bested the field average of 73.1. Woods won the Mercedes Championship in January 2000 to claim his fifth event in a row, yet a third-round 71 was just a hair better than the field average of 71.03. Another close call came in July, at the Western Open, where Tiger’s final-round 72 was only 0.2 strokes better than the field. The streak continued through wins at the Open Championship, the PGA, and the Bell Canadian Open (site of his famous 216-yard fairway bunker shot over water on No. 18). It continued through a third-place finish at the 2000 Disney and a runner-up at the Tour Championship. His final event of 2000 was the WGC-American Express Championship at Valderrama in November. Woods’s opening 71 beat the field by 0.4 strokes. Second- and third-round 69s thumped the field by 4.4 and 3.4 strokes, respectively, and he tied for third place.

On Sunday, Woods’s unimaginable streak was undone by the most pedestrian of golf exasperations. “I had a lot of really good putts that just didn’t go in,” he said after the round. “That’s just the way it goes sometimes. You put yourself there, and sometimes they go in. Sometimes they don’t.” His final-round 72 was not good enough to keep the streak alive. The field’s average score of 71.6 edged Woods by a mere 0.4 strokes.

I asked Woods about his extraordinary streak. “That, and my consecutive cut streak, are both gratifying,” he said.

Amazingly, Tiger was just one saved stroke away from extending his streak to 112 rounds.

Reflecting on that period, Woods added, “I was playing pretty good golf. I had that winning streak at the end of 1999 into 2000 and won three majors that year. It was a really fun stretch.”

[pagebreak]

As stunning as his 89-round streak was, had Woods scored just one shot better in the second round of the 1999 WGC-NEC Invitational, his beat-the-field achievement would have lasted 112 rounds, starting from the fourth round of the Byron Nelson in May 1999. (I only count stroke-play events for the streak, so this ignores, for example, the Sprint International tournament, which used Stableford scoring.) Die-hard baseball fans might know that after DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak ended on July 17, 1941—he went O-for-3, with two hard ground-outs to third base—he proceeded to hit safely in his next 16 games, so Joltin’ Joe was just one hit short of a 73-game streak.

Imagine that. With a bounce here or a birdie there, these feats of excellence and consistency might have been even more epic. In 1988, in the New York Review of Books, the eminent scientist Stephen Jay Gould wrote beautifully about DiMaggio’s run, saying, “Long streaks always are, and must be, a matter of extraordinary luck imposed upon great skill.” It boils down to this: It’s a statistical impossibility for an average-skilled player to sustain a formidable streak. The longest ones are the domain of the great players—but not all great players hold long streaks. Blame Lady Luck.

[pagebreak]

Will Tiger’s 89-round beat-the-field streak ever be broken? Almost certainly not. Not only has no golfer knocked on the door—no one has been sighted walking within a country mile of the house. (Because of a lack of reliable data prior to 1983, we may never know if Hogan, Palmer, Nicklaus or any other legends of yesteryear had a similar run.)

Who gets the nod—Tiger or Joltin’ Joe—for the greater accomplishment? Let the grillroom debate begin. On one hand, Tiger’s streak lasted more than a year, compared with two months for DiMaggio. My analysis suggests that Woods’s streak was a bigger outlier in sporting achievement, but that analysis involves judgment and assumptions, and doesn’t consider that the Yankee legend performed under the weight of the streak itself. When DiMaggio’s run reached into the 20s, newspapers started covering the streak. National attention grew more intense as the Yankee Clipper approached the record of 41 set by George Sisler in 1921. “You can’t imagine the strain [DiMaggio is under],” Sisler told the New York Daily News during Joe D’s sprint. “The newspapers keep mentioning the streak. Your teammates continually bring it up. You try to forget, but it can’t be done. It’s in your head every time you step to the plate.” While Woods put pressure on himself to win, he wasn’t grilled by the press about his streak while it was happening. It’s clear that neither Tiger nor golf fans knew it was happening at all.

We shouldn’t underestimate Tiger’s sheer will as he chases down Jack’s major record.

Grinding was, and is, in Tiger’s DNA. At his height, in 1999 and 2000, he was impervious to outside forces, because no one could press him more than he pressed himself. Woods’s sheer will ranks him with the greatest warriors in all of sport—and this inner steel shouldn’t be underestimated as the 14-time major winner tries to return to peak form and chase down Nicklaus’s major record.

Stephen Jay Gould summed up the importance of a streak when he wrote, “A man may labor for a professional lifetime, especially in sport or in battle, but posterity needs a single transcendent event to fix him in permanent memory… Detractors can argue forever about the general tenor of your life and works, but they can never erase a great event.”

Woods has authored many such events, and his beat-the-field streak might be the most transcendent—just as DiMaggio’s streak represented his peak. Both are ours to marvel at and enjoy.

For more news that golfers everywhere are talking about, follow @golf_com on Twitter, like us on Facebook, and subscribe to our YouTube video channel.