‘Impossible golf hole:’ Matt Fitzpatrick criticizes Riviera’s famed (and controversial) par-4

‘Impossible golf hole:’ Matt Fitzpatrick criticizes Riviera’s famed (and controversial) par-4

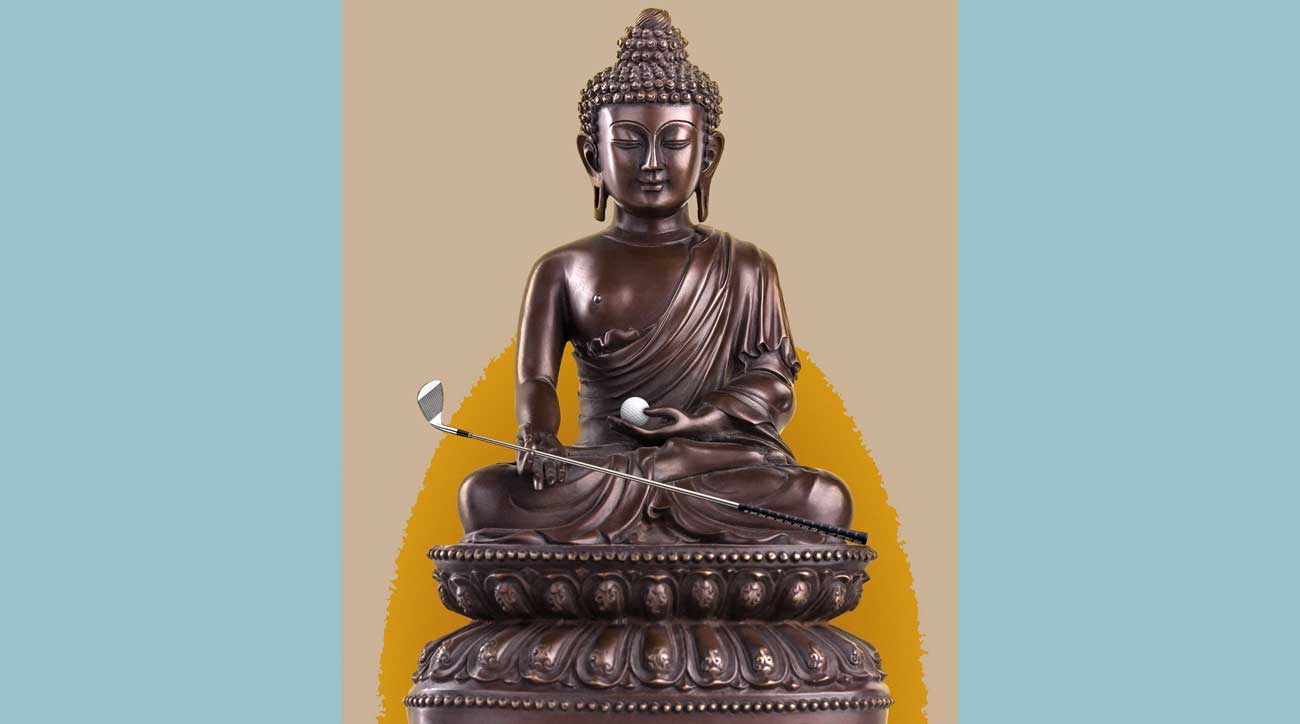

Emotional Rescue: Learning how to use — not lose — your mind on the course

The last time I was on a golf course, before I began taking lessons with GOLF Top 100 Teacher Jon Tattersall, was at my brother-in-law’s bachelor party in Buffalo. There, after one errant shot, I saw a man, who less than two hours earlier had been amiably chatting with me about baseball and fatherhood, throw his 3-iron at a golf cart and spend 20 minutes trying to figure out how to kick a tree.

Our pleasant recreational activity — a lovely day spent outdoors with a group of close friends — turned into a rage-fueled stomp through greenery, an exercise to see just how many veins the guy could pop out of his forehead. No wonder he played so lousy — but that’s what this game will do to you.

Over the past six months, Tattersall has patiently taught me the basics of the sport, but nothing we’ve covered can appropriately prepare me for whatever … that is. I’ve played baseball, basketball, soccer and tennis, and none of those games has made me want to strangle a squirrel. What is it about golf that makes people so insane?

“It’s very difficult, even for the best players,” Tattersall explains. “Even at the highest level, the game beats you up pretty good.” This is a sport seemingly built to maximize pain and frustration. I thought you people played it to relax!

The ability to keep one’s emotions in check is yet another thing that separates the pros from the rest of us. It’s not that great golfers don’t make bad shots. They’ve made thousands of them. The world’s best golfer has struck many more terrible shots than you have. The difference is that they don’t sweat them much.

“Most Tour players are delusional, and have a very helpful amnesia for the bad stuff,” Tattersall says. “They’re kinder to themselves than recreational golfers. They’ve tested their limits. They’ve been knocked in the teeth enough.”

That is to say: The time you’re spending cursing yourself after a shank? That’s time that a top player uses to prepare his or her next shot, because they’ve already forgotten the last one. Bad shots happen. All you can control is how you react to them. And that’s key.

“If you’re constantly reminding yourself of all your bad shots, you’re technically correct,” Tattersall says. “You have hit a ton of them. The trick is ignoring those outliers. Some shots will be better than average, and some shots will be worse. What matters is consistently raising that average.”

The best golfers know who they are and know what their median is. They know that sometimes they won’t be at their best, but they trust their games enough to know that eventually they’ll find themselves back in a good place. Every shot is one data point. Overreacting to one data point only does you harm.

ADVERTISEMENT

Here’s a routine misunderstanding about golf: When people talk about the game’s “mental challenge,” they think they’re referring to the struggle to control the mind. But what they really mean to say is, “I can’t control my emotions.” If you’re having a strong reaction to one golf shot, whether it’s a great one or a terrible one, you’ve already lost. The next shot is always the only one that exists.

That’s not to say that confidence doesn’t matter. “Brooks Koepka doesn’t think this game is mental at all right now,” Tattersall says. “He thinks he’s just the best player in the world, doing what he should be doing. And he’s probably right! There’s a benefit to feeling bulletproof.”

But on the whole, what golfers chalk up to “mental issues” or “the yips” has nothing at all to do with the mind. “It’s usually plain old technique,” Tattersall says. “You’re not shanking it because you’re a head case, you’re shanking it because your swing is a mess. Fix your swing and you’ll fix your game.”

Of course, this is all easy for Tattersall and me to say. Your tantrums are inefficient and self-destructive. The distance between that advice being sound and that advice being helpful is significant. I could have told my bachelor-party friend that trying to dislodge and hammer-throw a ball washer was simply him losing his s—, and that the time he spent acting out would have been better used to groove his takeaway. But had I done that, I’m pretty sure the next thing he tried to toss across the fairway would have been me.

Will Leitch is a columnist for GOLF, a contributing editor for New York Magazine, and the founder of Deadspin.

ADVERTISEMENT