The Open Championship has (finally) returned to Royal Portrush, but its quest back was not so simple

Graeme McDowell grew up in the tiny town of Portrush, on the northern tip of the Irish island. Like many before him, he came to America chasing a dream. In his case it was golf glory, which led McDowell to matriculate at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. He was baffled by more than just the accents and the cuisine. “I was overwhelmed by the patriotism,” McDowell says. “You go to a football or basketball game and it’s in the air, it’s part of the ritual. Even now having lived in the States for a long time, I still can get overwhelmed by it. I’ve never been patriotic because it’s very hard to be proud of where I grew up.”

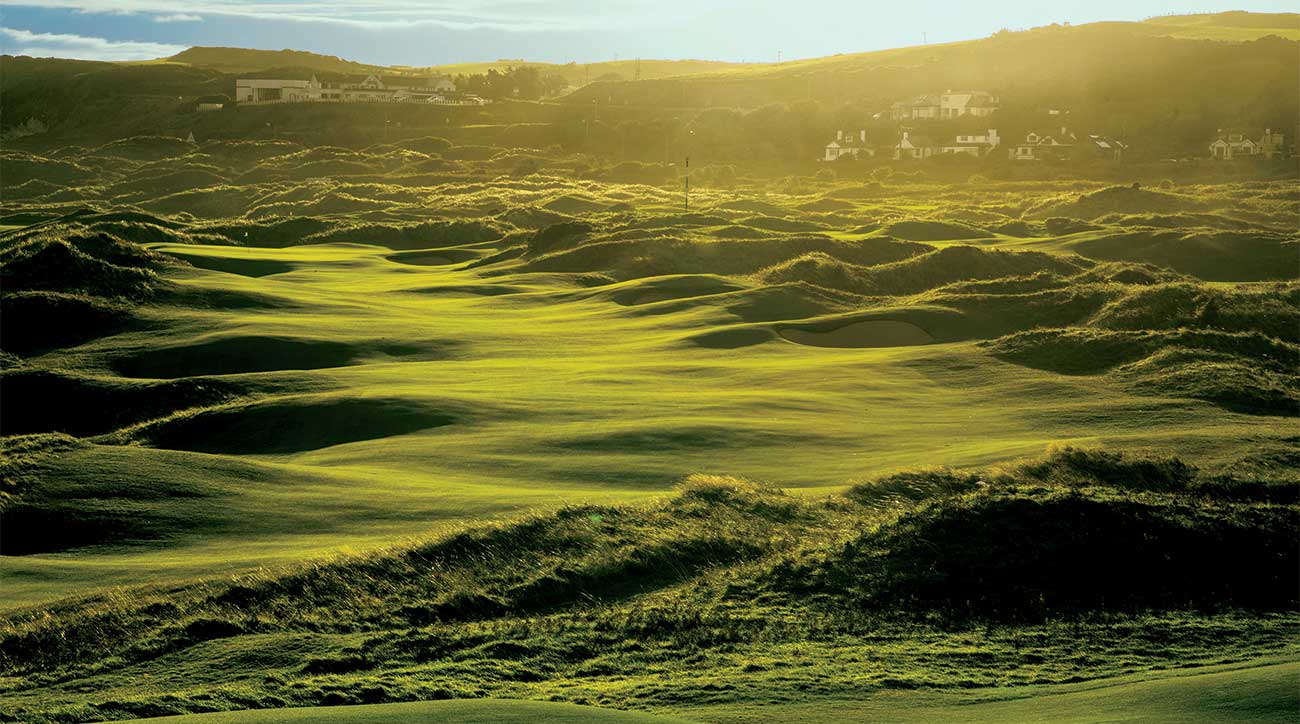

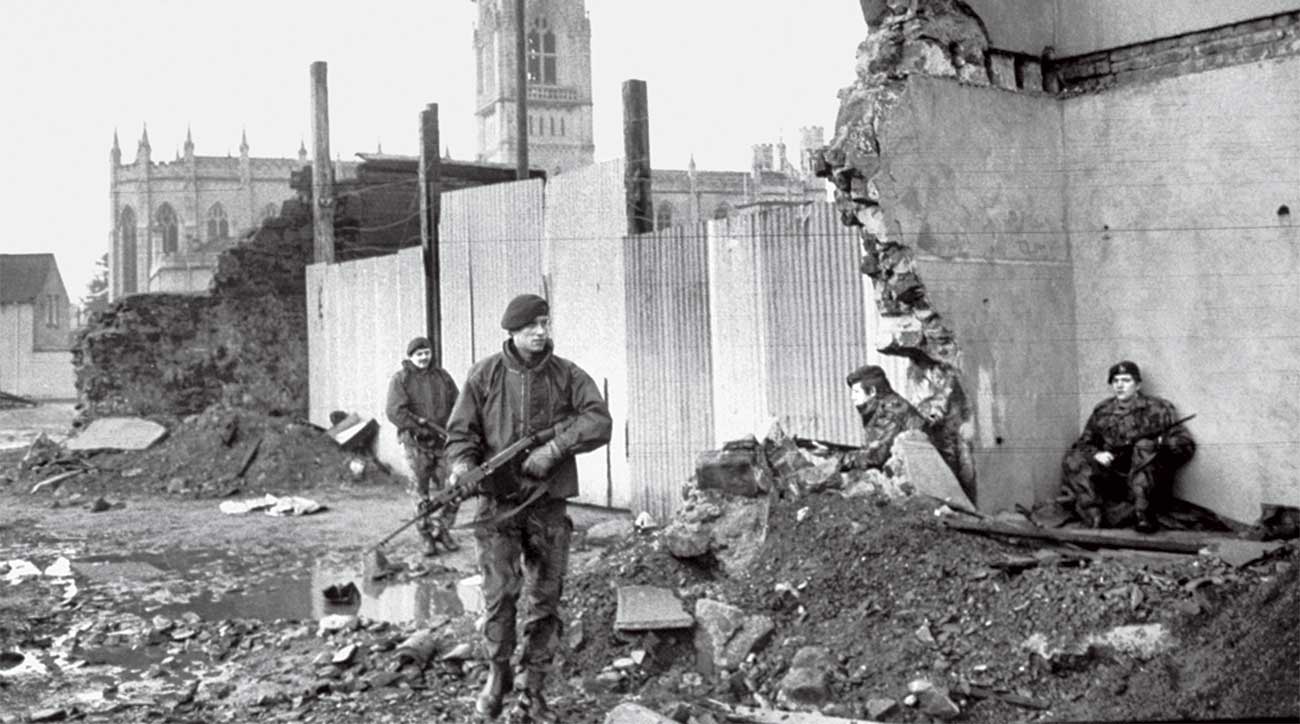

This has nothing to do with Portrush itself, which boasts gorgeous coastal views, a charming downtown and one of the most awe-inspiring golf courses in the world, the Dunluce Links at Royal Portrush. It was good enough to host the 1951 Open Championship, the first time the event had left Scotland or England. Royal Portrush should have become a fabled part of the rota, but beginning in the late 1960s all of Northern Ireland was engulfed in the civil war which came to be known euphemistically as the Troubles. The roots of the conflict dated back centuries, but the modern violence was fueled by a toxic mix of nationalism, religion and partisan politics. The Troubles simmered for three decades, pitting neighbor against neighbor and leading to more than 50,000 casualties and 3,500 deaths, often from indiscriminate bombings and deeply personal doorstep shootings. This was the Northern Ireland of McDowell’s youth.

The Good Friday Accords of 1998 brought an uneasy ceasefire. Slowly, the golf world began to venture back into Northern Ireland. Royal County Down summited various Top 100 lists, but it’s barely 15 miles north of the invisible border with the Republic of Ireland. Royal Portrush is two hours farther north, into the dark green heart of Northern Ireland. It became one of the game’s great pilgrimages, a dreamscape of heaving terrain, vertiginous dunes, devilish greens, fiendish bunkering and woolly weather, all of it shrouded in mystery. But Royal Portrush had the most charming ambassadors imaginable to help spread the good word: McDowell, who began playing the course as a wee lad; Darren Clarke, who grew up an hour away, became a member of Royal Portush, got one of his sons a job in the pro shop, and loves the club so much that the medal he won as the 2011 Open champion is now displayed there; and Rory McIlroy, who at age 16 shot a 61 there, which still stands as the course record. As these native sons began piling up major championship victories at the start of this decade, Northern Ireland became one of the golf capitals of the world. The tweedy traditionalists at the Royal & Ancient couldn’t help but take notice. The whisper campaign began to return the Open to Portrush. “I remember when all the talk started, it seemed like a dream,” says McDowell. “It seemed impossible.”

There were many reasons not to bring the Open back: the scoreboards, grandstands, corporate tents and other large-scale infrastructure would have to be shipped across the Irish Sea; the proud old course would need to be configured because the existing 18th hole was hemmed in by the clubhouse and first tee, and there was no space to build the trademark amphitheater that always surrounds the Open’s closing hole; the train station was inadequate for the teeming masses at golf’s biggest event; hotel beds were scarce. Unspoken but always lurking in the subtext was the fear that the fragile peace would not hold.

To their everlasting credit, the stewards of the R&A worked tirelessly to find solutions, pledging millions of pounds to improve roads and railways. The national police force (PSNI) took responsibility for a level of security that will be unprecedented at an Open. An audacious plan was hatched for the Dunluce to absorb two existing holes from its sister course, the Valley Links. In October 2015, the membership of Royal Portrush gathered to hear the final proposal from the R&A and vote on the fate of the Open. So many interested parties turned out that the meeting had to be moved out of the clubhouse into a larger space in a nearby hotel. Time does not heal all wounds, but it does present new opportunities. The vote was a simple showing of hands. Every arm reached for the sky, and the Open was, at long last, returning to the divided Irish island.

* * * * *

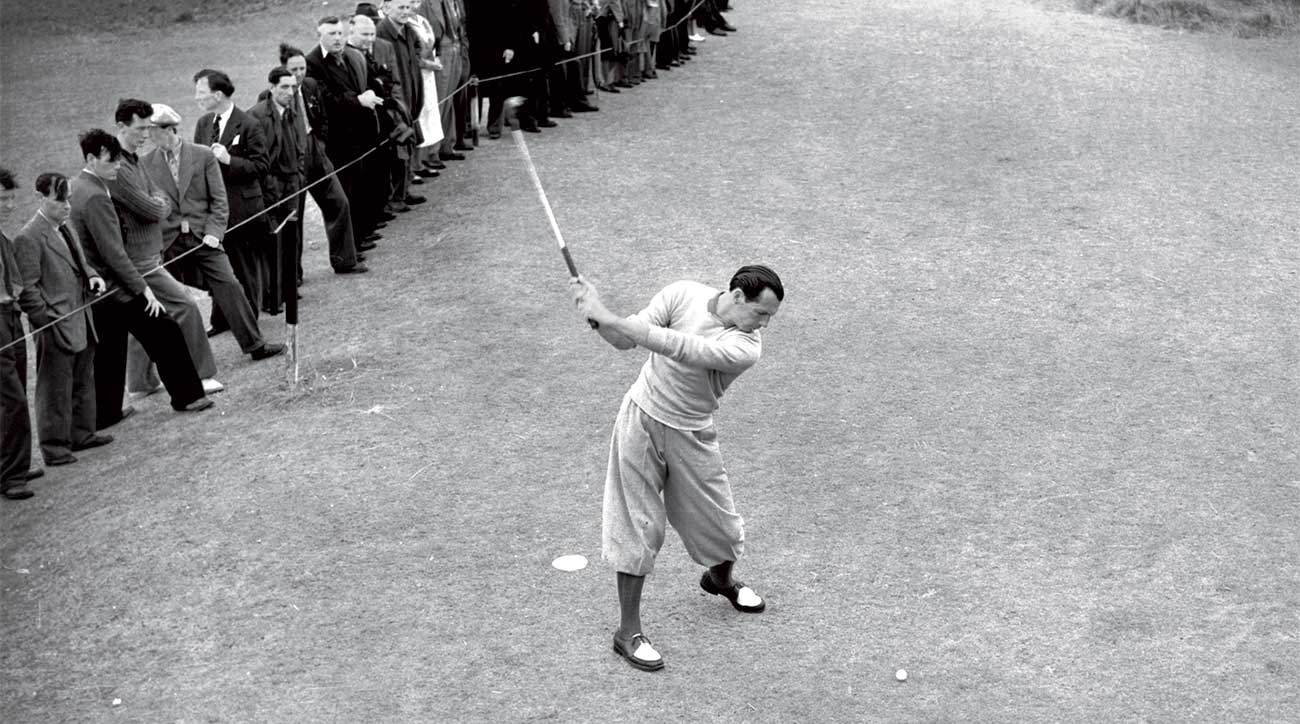

The doyen of the Royal Portrush Golf Club looks as exactly as you’d imagine: Ian Bamford is dressed in a blazer and tie, seated at a table in the clubhouse with ramrod posture, choosing every word with great precision. He was just a boy when the ’51 Open was played in his hometown, but he can still summon the feeling of that week. “There was great excitement in the air,” says Bamford, 88. “The Open was a smaller occasion back then, but golf has always been a part of the fabric of Portrush, and so the tournament’s arrival was quite heralded.”

Englishman Max Faulkner produced a dominant performance, going 71-70-70 to build a 6-stroke lead and then cruising home with a 74 to win by two, with a cumulative score of -3. Peter Thomson, 21, made an auspicious Open debut by tying for sixth. Only a handful of Americans competed because qualifying for the Open coincided with the PGA Championship at Oakmont, which was won by Sam Snead. “The players were very complimentary about the golf course,” says Bamford. “There was every expectation that the Open would return again soon.”

Bamford, the club historian, places the size of the crowd at 7,000 people per day. Oh, how times have changed. Tickets went on sale in October 2018 for Portrush’s encore, and within seven weeks all 190,000 tickets were gone, the first time in history the Open had sold out. After securing more water closets and other necessities, the R&A released a few thousand more tickets in April ’19, and they were snapped up in a matter of days. For the first time ever, there will be no walk-up ticket sales at the Open.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The R&A has been in shock, but we gently tried to tell them this was going to happen,” says Royal Portrush’s redoubtable secretary Wilma Erskine, who has been at the club for 35 years. Indeed, when the Irish Open came to Portrush in 2012, for the first time in 65 years, a European Tour attendance record was set at 112,000, and it would have been much more but organizers were forced to cut off tickets sales as the tournament infrastructure became overtaxed. That dress rehearsal was useful for illustrating all the upgrades that would be needed going forward. “I call this the plug-in Open,” says Erskine, noting the many new pieces that have been put in place: miles of fiber optic cables; an underground water and sewage system; £16 million worth of widened roads and a new train station. If all goes well, no one will really notice these upgrades, but the changes to the fabled course figure to be a lively talking point.

The first six holes remain the same sequentially, including the signature fifth, a steeply downhill par 4 with one of the best views in golf from the tee and a dangerous infinity green on the precipice of the sea. The seventh and eighth holes are the new ones reclaimed from parts of the Valley Links. Both are terrific. Number seven is a 590-yard par 5 that winds through some epic dunes, and the elevated tee shot is made fraught by the “Big Nellie” bunker; this vast expanse of sand is a re-creation of the celebrated hazard on the original, now-abandoned 17th hole, with that land to serve as the site of the spectator village during the Open. “It’s visually intimidating,” says McIlroy. “It’s visually spectacular.” The new eighth hole is an exacting dogleg-left par 4, forcing players to drive over the dunes to a narrow, slanting fairway. Awaiting is one of Portrush’s most memorable greens, featuring a huge false front that can wreak havoc in the wind. What was the original seventh hole now plays as the ninth, and then the course picks up from there as it always has. (A labyrinth of new underground tunnels will help players move seamlessly from green to tee.) This means that the famous par 3 nicknamed Calamity Corner—an uphill, 230-yard carry over a yawning void—now plays as the 16th hole, a perfect spot in the round for a do-or-die swing.

If there was a nitpicking critique of the old Royal Portrush it was that the final two holes departed the dunes for flatter, more boring terrain that offered little resistance to scoring. It was an unbecoming ending to a bold layout that has a grander scale than any other Open course. Now Portrush has the rollicking finish it deserves, with the original 15th hole playing as the new 17th. This 405-yard par 4 requires a blind tee shot over the dunes to a fairway that runs steeply to the green, making it potentially drivable. The home hole becomes a 465-yard par 4 bending to the right around some gnarly dunes, with out-of-bounds running down the left side of the fairway. From the tee, with the Open potentially hanging in the balance, players are asked a basic but tough question: How much of the dogleg do I dare cut off?

“I like all of the changes,” says Darren Clarke. “It’s like a jewel that has been given a polishing.”

Portrush now tips the scales at 7,337 yards, with the perfect mix of long, tough holes and shorter ones that offer enticing risk-reward. “I think it will be one of the most thrilling Opens we’ve seen,” says Padraig Harrington. “There are holes there that are very gettable, but there are other places it can get you back. That’s what I like: It gives and it takes.”

“I think it will quickly rise to the top of the rota courses,” says Seamus Power, a native of Waterford, Ireland, who is currently playing on the PGA Tour. “It’s difficult, but a good shot is rewarded there and that’s all you want in a tournament setting. I think it will be an incredible showcase for true Irish golf.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Martin Slumbers, the chief executive of the R&A, sees all the tweaks to Royal Portrush as symbolic of something larger. “It’s not an easy thing to go to a club that is 130 years old and say, ‘We love your golf course, but now we want you to change it,’ ” says Slumbers with a little chuckle. “That the membership and leadership of Royal Portrush have embraced all of this so enthusiastically speaks volumes about the spirit of collaboration that has characterized the planning of this Open Championship at every step of the way.”

* * * * *

Spring cleaning took on a different meaning this year in the village of Portrush. Businesses put up new awnings while homeowners added a fresh coat of paint. A local heritage group has adorned the town with signage highlighting its history and attractions. “This is by far the biggest event ever to come to Northern Ireland,” says Erskine. “We all want to put our best foot forward.” Royal Portrush is heavily subsidized by vagabond Americans, who account for three-quarters of the overseas visitors. The Open will be a week-long infomercial to entice golfers from the rest of the world. “The economic benefits to the whole of Northern Ireland can’t be overstated,” says Erskine.

McDowell is more focused on the political overtones for a part of the world where golf is the only shared religion. “I think Ireland will feel as one,” he says. “The whole island will feel tremendous pride. It’s a chance to bring all of Ireland together. Perhaps politically it can accelerate a unified Ireland.”

This is the kind of fairy tale that sportswriters find irresistible, but reality can be far messier, as Brexit has illustrated. The Republic of Ireland is part of the European Union and shall remain so. Northern Ireland is aligned politically with Great Britain and thus will be compelled to leave the EU if Brexit is ever consummated. At various points in the rancorous negotiations, there have been calls for a hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland to control the flow of goods and services. The threat of building a wall has inflamed old tribal tensions. A bloody nadir was reached on the night of April 18, 2019, in the town of Derry, 35 miles west of Portrush, which a year earlier had been the site of rioting that evoked memories of the Troubles. This time a police sweep led to crowds pelting officers with stones and petrol bombs. A member of the paramilitary group New Irish Republic Army opened fire at what was deemed “enemy forces,” and 29-year-old reporter Lyra McKee was caught in the crossfire. Her death has sent shock waves throughout the region.

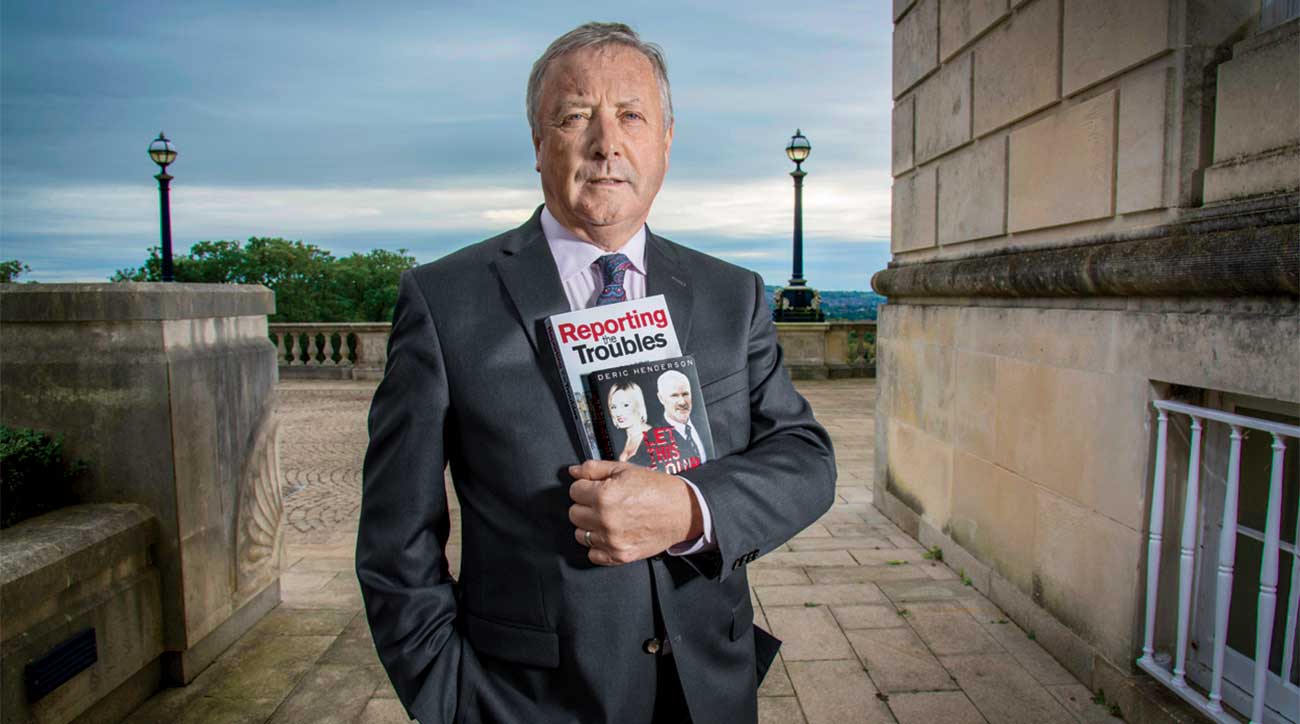

Come what may, the Open will still be played, as it must. Long before McKee’s murder, those around Royal Portrush were steeled for some sort of trouble in the run-up. Deric Henderson, a longtime member and former editor of the Ireland Press Association, says, “Believe it or not, the people of Northern Ireland are an optimistic bunch. The overall attitude has always been, ‘No matter what happens, we will carry on, as we always have.’”

And so the 148th Open will stir deep emotions that transcend golf. Already bubbling up in Graeme McDowell is a pride of place that feels entirely foreign. “We’ve gone through a huge amount,” he says of his fellow countrymen. “There have been dark times. There is still some darkness. As I said, there’ve been many times when I’ve looked around and seen how proud people are of their country, and I’ve thought to myself, Man, I don’t have that. I always wished I did. It sounds funny in a way, but when the Open Championship begins at Portrush, I know I’m going to feel more patriotic than I’ve ever been in my life.”