During the 2015 Masters Tournament, Lanny Wiles did what any other visitor to Augusta National Golf Club would try to do: buy himself a souvenir to commemorate his trip to a place most golfers spend a lifetime vainly dreaming of going. Wiles, hoping to avoid the crowds at the merchandise pavilion, approached the pro shop near the clubhouse. A bored security guard at the shop’s entrance stopped him and asked to see his patron’s badge—the coveted token that would ensure his entry.

“Sorry, I don’t have one,” Wiles told the guard.

“Then you can’t go in,” the guard replied, probably for the hundredth time during his shift.

Unlike many of the other visitors to Augusta National that day, however, Wiles had been in this particular pro shop once before. In October 1983, he took time off from his job running a Jacksonville Bojangles’ franchise to help his former boss, President Ronald Reagan. The Old Man, as Wiles still calls him, was headed to Augusta to play a round of golf with a Republican donor and members of his cabinet. Wiles, a Republican political operative who had worked for Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign handling the balloon drop at rallies, was serving as advance man for Reagan’s entourage, which had set up shop at the Eisenhower Cabin. For his loyalty and hard work, Wiles was promised a round on the famed course, playing in a foursome just ahead of Reagan’s.

Wiles never got his reward. Instead of playing his way through Tea Olive and Flowering Peach and eventually around Amen Corner, Wiles found himself in the pro shop, a Smith & Wesson .38 pointed squarely between his eyes by an unemployed millwright wearing a baseball cap embroidered with the words “Heaven is a Lot Like Dixie,” and smelling a lot like vodka.

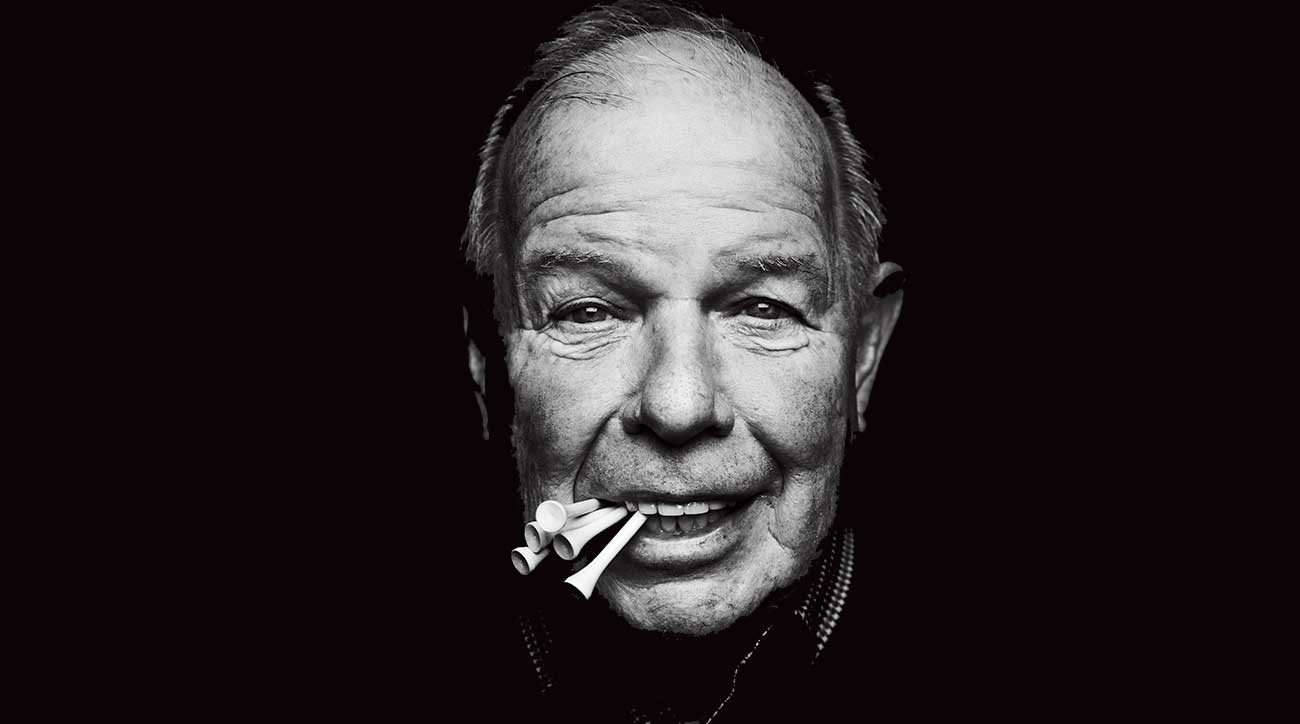

“Ever stuck a water glass between your eyes?” Wiles asks, his story by now a practiced rap honed at countless cocktail parties. “That’s how big the barrel of that gun looked to me.”

The memory of that gun flashed through his mind as he looked the guard in the eye and offered a rueful smile. “You know,” Wiles told him, pointing toward the door, “I almost lost my life in that shop.”

Now he had the guard’s full attention. “You were one of the hostages?”

Wiles nodded. The guard let him into the place, where he bought a golf shirt tastefully emblazoned with the club’s logo.

And almost 35 years later, Lanny Wiles still hasn’t played a round at Augusta National.

* * * * *

Ever since Charles Harris voted for Ronald Reagan in November 1980, his life had come apart at what were once very tightly sewn seams. Almost three years later, Harris was 45 years old and struggling badly. His father, a Navy veteran and retired Augusta detective, had died after a prolonged illness. In part, Harris coped with the loss by drinking heavily. When he showed up intoxicated at work one day, he was fired from his millwright job at Continental Forest Industries. By all accounts, he’d been a good and loyal employee in his 23 years there (his fellow union members had elected him their shop steward), but it wasn’t enough to save his job. On top of all that, Harris’s marriage was falling apart.

Such was the state of Harris’s life that Saturday morning in October as he and his sister drove down Washington Road, near Augusta National. The two took notice of the tight security and wondered what the fuss was about. Up ahead, Harris recognized a county deputy standing guard outside one of the club’s gates.

“Mitch, who you got in there?” Harris asked.

“The President’s here to play golf,” the deputy told him. “An ant can’t crawl in there.”

With good reason. Reagan had survived an assassination attempt a little more than two years earlier, outside the Washington Hilton. Shooter John W. Hinckley Jr. told investigators he was trying to impress actress Jodie Foster by making a run at Reagan; three other people, including Reagan’s press secretary, James Brady, were shot in the incident.

Harris drove home and downed a drink. He switched on the TV, only to hear a report that U.S. Steel was planning to lay off thousands of workers. The news sent Harris into a rage. He tried to calm himself by pouring another drink, but his ire—and the combination of woes in his life—set him off again. He knew what he’d do. He’d go back to Augusta National and have a talk with Ron Reagan. After all, he’d voted for the guy. So why wouldn’t Ron—who was just playing golf, after all—want to talk about the plight of American workers like Harris? And here he was, right in town.

Harris got back into his truck, pointed it toward Magnolia Lane and hammered the gas pedal. He had a .38 caliber revolver with him.

* * * * *

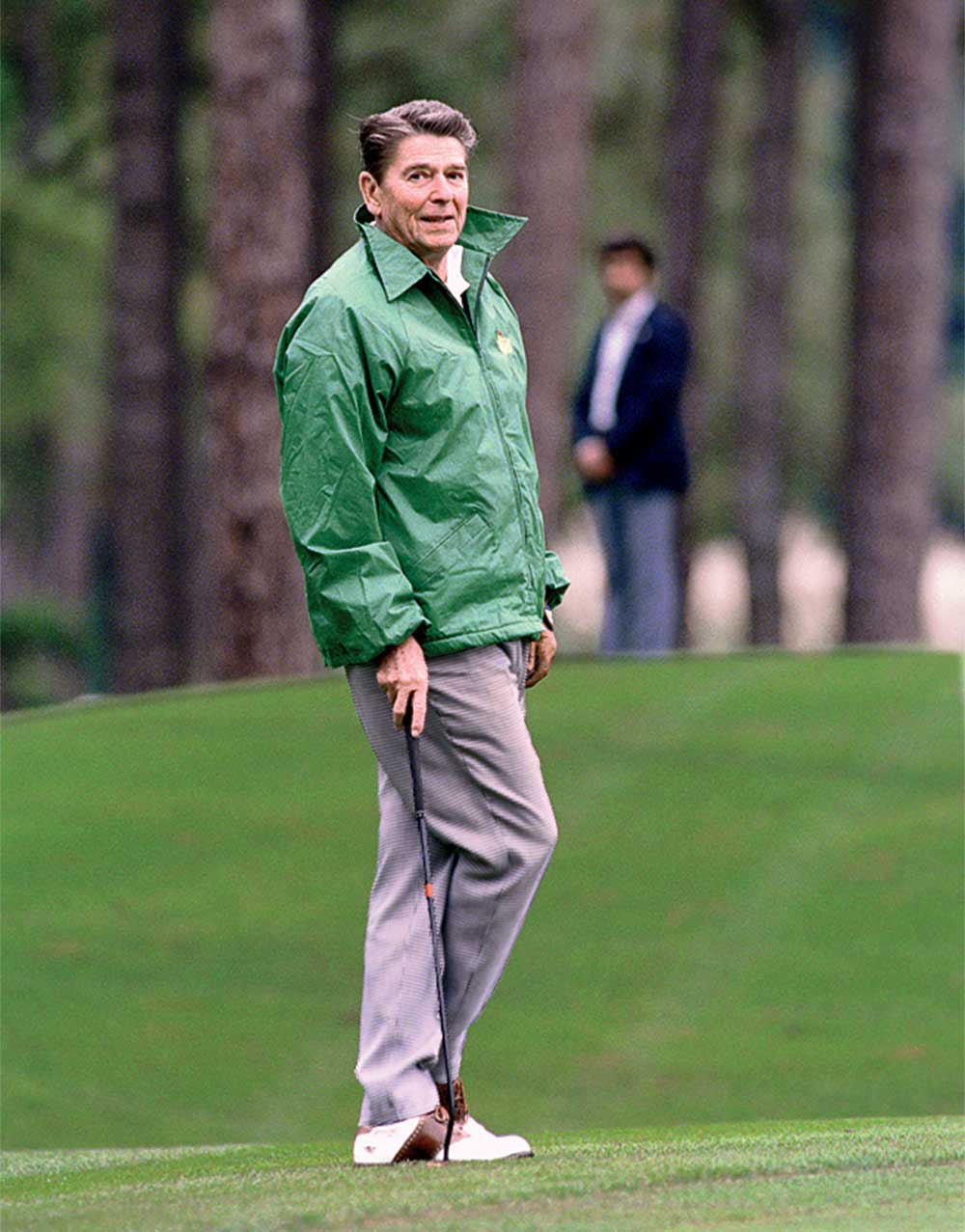

Ronald Reagan was the kind of bad golfer who gave bad golfers a bad name. “When I became president, my golf game took a dramatic nosedive,” Reagan once said. Ranked among the worst presidential golfers in history by author Don Van Natta Jr. in his book First Off the Tee, Reagan may have been less of a hack had he teed it up more often—Van Natta notes Reagan played only 12 rounds during his eight years in office. Whenever reporters asked Reagan to reveal what his handicap was, he’d reply, “Congress.” Yet every year, on New Year’s Eve, the President dug his clubs out of hibernation for a loop at Sunnylands, the California estate owned by Walter Annenberg, the publishing magnate and former ambassador to Great Britain.

At Augusta National, the President was the guest of member Nicholas Brady, a former Republican senator from New Jersey and then-chairman of filter manufacturer Purolator, and joined by the administration’s two biggest golf enthusiasts: George Shultz, the Secretary of State, and Don Regan, the Secretary of the Treasury.

Ahead of Reagan’s foursome, Wiles was to play with David Fischer, the President’s long-time personal aide, Robert “Bud” McFarlane, the national security adviser, and a local member.

Wiles waited on the first tee, ball in hand and ready to plant his peg, when McFarlane was whisked away by aides for a secure phone call. (It may have had to do with preparations for the U.S. invasion of Grenada, which started three days later.) The group stepped back and let the President take the tee. Wiles waited while McFarlane talked. And talked. And talked. He decided to trail the President and take in his round rather than play his own. It’s a decision he regrets to this day.

Reagan and his power foursome played on, then stopped at the turn for lunch in the clubhouse. When they resumed at the 10th, Reagan, feeling a chill, asked Wiles to fetch him a light jacket. Wiles rejoined the group in the heart of Amen Corner. Number 12, Golden Bell, is Augusta’s shortest hole at 155 yards, but that didn’t stop the Gipper from making a mess of the beauty. He tugged his tee shot into Rae’s Creek, flared his mulligan once again into the drink, and when Shultz graciously teed up a third ball for him, Reagan came up short of the water altogether.

“I can’t watch this anymore,” Wiles told Fischer. “I’m going to do some shopping. Want to come?”

The two of them hopped into a cart and sped off for the pro shop.

It was just after 2:00 p.m.

* * * * *

Charles Harris plowed his four-wheel-drive, blue-and-silver 1974 Dodge pickup truck through the gate east of Magnolia Lane. He continued several hundred feet up a single-lane road to a parking lot where Roy Sullivan, a club chauffeur, was unpacking someone’s sticks. Harris shoved his .38 into Sullivan’s back and duck-walked him past a press building and across a small road to the pro shop.

Wiles remembers that he was looking at a miniaturized golf bag, wondering if his mother-in-law might like it, when he heard someone say, “Everyone in the back room.”

He turned to see Harris, his doughy face fringed with a grizzled beard and topped by that Dixie baseball cap. He had on sneakers, along with a red Atlanta Falcons practice jersey over his broad shoulders. His jeans were held up by a pair of suspenders. Harris grabbed Sullivan in a headlock with one arm and pointed the .38 at the back of his head with the other. Fischer, his brow pleated with worry, whispered to Wiles that it was a robbery.

“I knew it wasn’t a robbery,” Wiles says. “I told him, ‘Get rid of your radio. He’ll know we’re with the President.’ I dropped mine in a towel basket.”

Harris herded Fischer and Wiles into the shop’s back room, along with Jim Armstrong, Augusta National’s general manager, and two pro shop employees. Harris immediately released Sullivan, telling him that if he looked behind the seat of his truck, he’d find a bottle of tequila. “I’d be pleased if you drank it all,” Harris told him.

After a few tense moments, Fischer asked Harris what he wanted.

“I want to see that son of a bitch on the golf course,” Harris barked.

“Well, that could be anybody, but we had a pretty good idea who he meant,” Wiles says now.

Fischer convinced Harris he might be able to serve as an intermediary with Reagan, so Harris released him, too.

Harris wanted an audience with the President to discuss his string of misfortunes. As if to warm up, he shared his story with the remaining hostages.

“I don’t think he was a bad guy,” Wiles says. “He had the weight of the world on his shoulders. Everything that could go wrong for this guy had gone wrong.”

After venting, Harris considered the two young shop assistants. “They were as nervous as a hooker in church,” Wiles says.

One of them, Kris Hardy, leaned against the counter behind the cash register, nervously tapping his toe. When Harris learned Hardy was only 19, he said, “You guys are too young to die. Get out of here!” Then he looked at Armstrong, knees quaking, a pale look of distress on his face. “You look like you’re going to piss in your pants. Get out of here!”

Then Harris turned to Wiles.

“So now it’s just the two of us,” Wiles remembers, “and the first thing he says is, ‘You know they’re going to come inside and kill us, don’t you?’ I said, ‘No one has to die here today. My wife’s pregnant and due with our first baby in March, and I plan to be there. Tell me what you want and I’ll make sure that’s what you get. No more, no less.’”

Harris asked Wiles what he was doing at the pro shop. Locking eyes, he told Harris he was just a bystander, a guy who had talked his way in from the street to purchase a shirt. Harris wasn’t buying it. He shoved Wiles against a wall, cocked the .38 and shoved it between Wiles’s eyes.

“I remember he said, ‘This is the moment of truth. Raise your right hand.’ All sorts of weird thoughts went through my head,” Wiles says. “He asked me, ‘Have you had a drink of liquor today?’ Well, I could smell liquor on his breath. So I said, ‘Charlie, if you count after midnight as today, then I sure have.’ He said, ‘I just wanted to see if you were a drinking man. Let’s see if we can find a drink.’” Harris lowered the gun. Then the two ransacked the office in a futile search for a bottle of booze.

Suddenly there was a knock at the door. It was Mitch, the same county deputy who earlier that day had told Harris and his sister about Reagan’s round. Mitch was trying to play peacemaker, but his efforts sent Harris into another fit of rage.

Wiles remembers, “All of a sudden, boom, he shoots out the shop’s front window and says, ‘You sons of bitches. It wasn’t loaded, but it is now.’”

The bullet ripped a hole in the pane and, for decades to come, became a showpiece of Augusta National tours, right alongside the display case that holds Bobby Jones’s clubs in the Trophy Room. “They kept it there forever,” Kris Hardy says. “I think it finally got replaced during a remodel.”

* * * * *

Reagan was playing Redbud, the par-3 16th hole, when Secret Service agents, alerted to the pro shop standoff, intercepted him just as Brady stiffed his tee shot to two feet. He never got to tap in for birdie, a putt that would have clinched the match but instead forever became a sore subject for the future U.S. Secretary of the Treasury.

Briefed on the hostage situation, Reagan demanded to be involved. From the safety of an armored limousine on the far end of the property, he used a primitive car phone to instruct a White House operator to patch him through to the shop. Wiles answered and heard a disembodied voice intone, “Stand by for Rawhide,” the President’s Secret Service code name. He handed the phone to Harris.

“This is the President of the United States,” Reagan said into the phone, according to a transcript of his side of the conversation. “This is Ronald Reagan. I understand you want to talk to me.” After a pause, he resumed. “This is the President. If you’re hearing me, would you please tell me and we can have that talk that you wanted.”

But the connection was spotty, and as the phone crackled with static Harris slammed down the receiver. Reagan redialed at least five times, to no avail. Finally, Harris ripped the phone out of the wall and hurled it across the room. “You’d think the son of a bitch would have a phone that would work,” he railed.

To this day, Wiles is convinced that had the connection been clearer, Reagan would’ve talked Harris off the ledge. Instead, eyes flashing with impatience, Harris grabbed Wiles and slammed him against the wall again. “They’re going to kill us,” he said.

All Harris wanted was to talk to the President.

“I’ll give you my gun when he shows his face through that door,” Harris told Wiles, his voice high with anger and thin with fear. “I’ve risked my life here. I’m not going to hurt anybody. I just want to talk to the man.”

Agitated and becoming more and more unhinged, Harris went off like a Roman candle and kicked in a door to a restroom. There was a scream. Out popped Louise Cook, a club secretary, and Dave Spencer, one of Augusta’s head professionals. Both had been hiding in the bathroom since the incident began. “Unfortunately, the window in the bathroom had been painted shut,” Kris Hardy remembers. “They couldn’t escape.”

Harris brandished his pistol, which caused Cook to faint. Wiles swept in and, when Cook regained consciousness, helped her crawl out the pro shop door to safety.

The three men remaining there fell into a conspiracy of silence, watching the Tennessee-Georgia Tech football game on a shop TV. Suddenly, the network broke into the game coverage with a special report on the hostage situation at Augusta National. Video showed Reagan speeding away from the course, followed by an open convertible carrying 10 Secret Service agents—two standing on the running boards of the vehicle—wearing blue blazers, khaki pants and argyle socks, toting Uzis on their hips. Reagan rode in the back seat of the limo with Shultz, and as the motorcade sped east on Washington Road, he waved at the crowds gathered across from the course.

The limo traveled just a short distance to another gate, reentered the club grounds, and headed down a private road to the Eisenhower Cabin, a six-bedroom villa named for the former general and president, an inveterate golfer and Augusta National member who made 29 trips to the club during his presidency.

Still, the image of Reagan in what appeared to be full retreat left Harris crestfallen. Wiles remembers: “He’s starting to digest what’s going on and he said, ‘We’re going to be here a long time. We may need some food.’”

Wiles knew he needed a diversion, and joked that they could all use a stiff drink, preferably from a fifth of Jack Daniels. He suggested that Spencer was just the guy to fetch them some liquor. Harris, with a powerful thirst for vodka, got firmly behind the plan.

“Dave has not said a word to this point, he was so dry-mouthed,” Wiles recalls. “All of a sudden he says in a voice we could hardly hear, ‘Can I get a glass of white wine?’ Wrong thing to say to Charlie. I kicked Dave so hard under the table that he said, ‘I’ll just take a Coke.’”

All signs pointed to Spencer being the next hostage to be freed—sent in search of booze. But Harris told him to sit down.

Wiles picks up the story: “Charlie said, ‘Lanny’s my friend. He’ll come back.’ He took me over to the door. I opened it with my left hand. He had that gun in my rib cage. I looked outside. I never saw so many guns pointed at me. It felt like being on the wrong side at the carnival, where they shoot the ducks with all those cork guns. They said, ‘Okay, Harris, give it up, it’s all over.’ He told them, ‘Do I have to kill this boy right now?’ I looked Charlie square in the eye and said, ‘Do you want a drink of liquor or not?’ He just pushed me out the door.”

Wiles sketched a diagram of the room for the Secret Service agents, and pinpointed Spencer’s location. Plans were drawn up to have a sharpshooter take out Harris. When a local sheriff contacted Harris to attempt another negotiation, the gunman demanded to talk to Wiles, who offered to go back into the pro shop. “I said, ‘I can hang with this guy,’” Wiles says. “That was pretty stupid, I’ll admit it. But they wouldn’t let me. I told Charlie they would let him have food but no alcohol.”

Harris had Spencer open the door to get the food. With Harris momentarily distracted, Spencer—the lone remaining hostage—dove out the door to safety. His bargaining position seriously eroded, Harris stayed holed up even after his mother and estranged wife had been brought to the scene to try to persuade him to drop his weapon. Eventually he did, and authorities cuffed and whisked Harris off to the Richmond County Jail.

After just two hours, the standoff was over.

* * * * *

The Secret Service took Wiles and the other freed hostages to the Eisenhower Cabin, where Reagan and his wife, Nancy, greeted them. “Nancy Reagan gave me a big hug and told me she was sorry,” says Hardy, who still lives in Augusta. “It was kind of cool. That’s the last time I shook hands with a president.”

Reagan asked Wiles if he had been scared. “With all due respect, Mr. President, I’m not going to let my wife touch my underwear when I get home,” he joked.

That night, Harris was rushed to University Hospital in Augusta after complaining of chest pains and collapsing in his cell. A hospital spokesman said he was treated for hyperventilation and given oxygen. Harris had alcohol on his breath at 11:30 p.m., seven hours after he was taken into custody, cardiologist David W. Cundey told a reporter for the New York Times.

It was after midnight when Wiles finally got the stiff drink he needed. He was enjoying it at the bar in his hotel when Fischer paged him. “He told me to go to my room and turn on the TV,” Wiles says.

The hostage drama Wiles had just lived was about to become yesterday’s news. Earlier that evening, 241 American service personnel were killed when a suicide bomber plowed a truckload of explosives into their barracks at the Beirut airport. Wiles hurried back to Augusta National during a torrential rainstorm, as the Secret Service positioned the President’s limo at the door of the Eisenhower Cabin. Reagan was being rushed back to Washington. Wiles remembers wearing a new pair of Gucci loafers and carrying Mrs. Reagan over a puddle. “Ruined my damn shoes,” he says. “I had a bad night’s sleep, too. I had a dream I was chased through the pro shop with a 3-iron.”

According to the Augusta Chronicle, Harris pleaded guilty on January 30, 1984, to kidnapping the chauffeur, false imprisonment and criminal damage to property in the second degree. No federal charges were ever filed. Harris was sentenced to 10 years in a Georgia state prison; he ended up serving three and a half years before being paroled in 1987. Judge Albert Pickett called Harris a reformed man, “one of those rare cases in which the probationer is worthy of early release from his sentence.” It may have had something to do with the Bible a guard had given him during his time in jail.

Once released, Harris reunited with his wife, Eleanor, stopped drinking and served as a Sunday school teacher and lay leader of his Methodist church. He died of a heart attack on July 4, 2007. He was 68.

There are now massive bollards posted at some of Augusta National’s gates to ensure that no one can ever repeat what Harris did 35 years ago.

* * * * *

Wiles returned to the political world, becoming a prominent lobbyist and political operative. He led Jack Kemp’s failed 1988 presidential bid and orchestrated John McCain’s 2008 Straight Talk Express. More recently, his name has been connected to the Trump administration. Wiles was tied to a Russian lawyer accused of meeting with Donald Trump Jr.; his ex-wife, Susie, served as candidate Trump’s Florida campaign manager; and their daughter Caroline served as Trump’s first White House scheduler.

Augusta National is one of the most exclusive golf clubs in the world. Membership is by invitation only; there is no application process. It is most decidedly not open to the public for play, and one gets the sense that the masses that descend on the course every April for the Masters Tournament are barely tolerated by the club’s 300 or so power-elite members, a cost of doing business among the magnolias. In order to step a spiked foot on the course, a player must be invited and escorted by a member in good standing, or be the spouse of one. You don’t just drive up and unload your sticks at the club drop.

Wiles has helped political candidates become elected officials in all sorts of offices through the years, but he has yet to win the campaign that is perhaps most important to him. The round at Augusta National, promised long ago on an unexpectedly turbulent October day, still hasn’t happened, despite Wiles’s best efforts to wheedle members, and friends of members, to host him on that hallowed track. “It’s at the top of my bucket list,” he says.

“Only guests of a member can play at Augusta National,” says an unsurprisingly officious club spokesman. “We don’t extend invitations otherwise.”

Well, at least Lanny Wiles has that golf shirt.