For second straight week, PGA Tour course moves in troubling direction

For second straight week, PGA Tour course moves in troubling direction

Why Tiger Woods’ memoir could (and likely will) be one of his most important achievements

A caveat, painful though it is to type. Many, if not most, of my predictions about Tiger Woods, over the last 24 years, have been when wrong. And yet: I believe Tiger Woods announced his retirement this week. It’s in the subtext of a press release about a book he is writing.

There was no announced publication date for the book. If the publisher, HarperOne, had one, it would have been trumpeted. The guess here is the book will be excellent, and that it will come out on the last Tuesday in April in 2022, after the Masters and before the PGA Championship, when Woods will be 46. Jack Nicklaus was 46 when he won the 1986 Masters, his 20th and final major, professional and amateur titles combined.

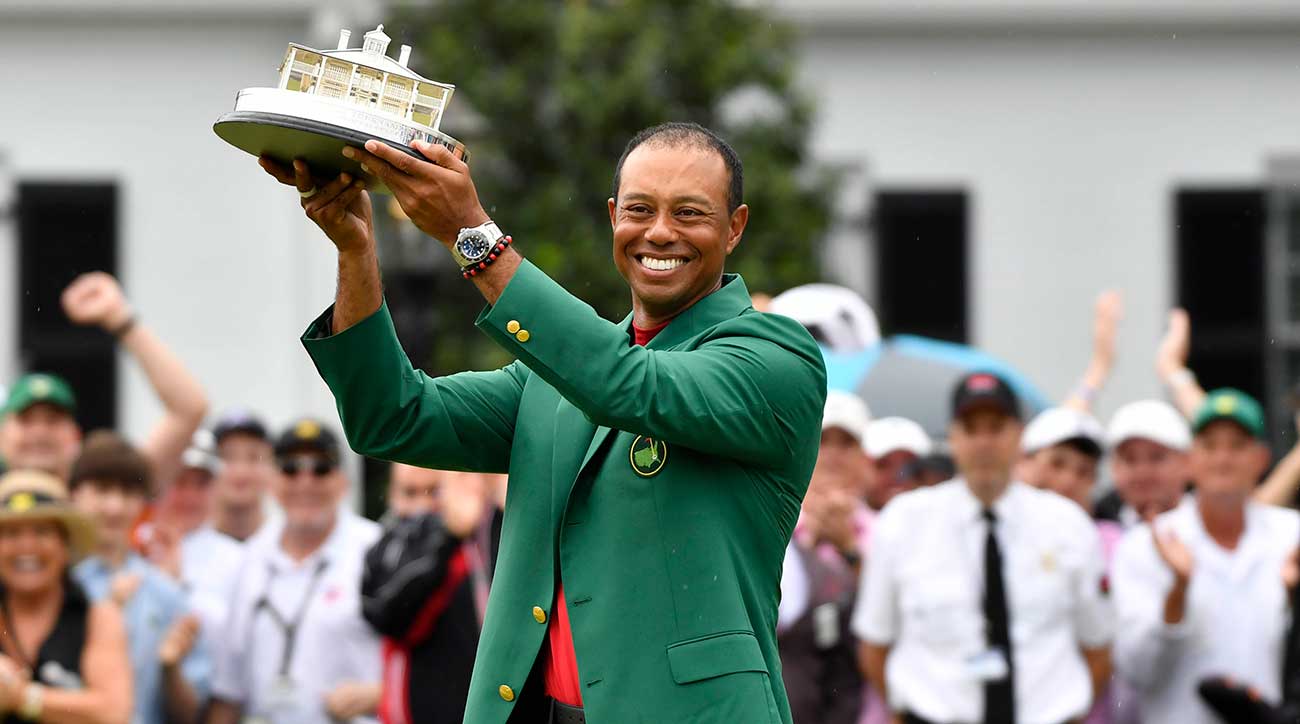

You can imagine Woods using the occasion of the book’s release to announce, with a sly nod to Nicklaus and one of his best phrases, that henceforth he will be a “ceremonial golfer.” At a minimum, he’ll have 18 majors himself then, professional and amateur combined. His professional career, the guts of it, will be a nice, neat quarter century.

He’ll keep playing the Masters and some other events, but he will have lowered expectations so much that the numbing pressure on him to win will have largely evaporated. He’ll feel like a new man. The book’s truthfulness will only help him in that regard. It will help his mental and physical health.

Book pub dates are traditionally on Tuesdays, hence the nod to Tuesday. Woods would not want the book to come out before the Masters for fear of stealing the tournament’s thunder. The publishers who work with Woods, and particularly his ghostwriter if he has one, may be surprised to learn there is a basic modesty to him.

The book, coupled with his new status as a ceremonial golfer, will pave the way for the rest of Woods’s public life, as course architect, team captain and assistant captain and advisor, golfing elder statesman, philanthropist and restaurant owner, all while enjoying the freedom that comes from being unchained from the secrets of one’s past. You can expect Woods to explore his complex feelings for fame, wealth, the game that made him and nearly broke him and made him again, his management team, Augusta National, other players, his caddies, his own body, his drug and alcohol use and the media spying that turned his private life inside out in 2009 and 2010.

“This book is my definitive story,” Woods said in the press release. He is now under obligation to make those words true.

In the press release, Woods says he is writing the book already. His editor is named. A ghostwriter is not. Maybe, like Barack Obama and Bruce Springsteen, to cite two other famous people who wrote memoirs without a ghostwriter, Woods doesn’t feel he needs one. But if he does, J.R. Moehringer would be a superb choice, and the guess here is that Moehringer is already in, or on his way.

In 2016, an announcement on Woods’s website described a work-in-progress about the 1997 Masters. At that point, the ’97 Masters book had no title but did have a ghostwriter, Lorne Rubenstein, a veteran golf writer from Canada. Tuesday’s announcement for this memoir by Woods included a title but not the name of a ghostwriter. Moehringer, in his two at-bats as a ghostwriter, didn’t have his name on the book’s cover. That’s not how he thinks or works.

The memoir announced on Tuesday has an excellent, four-letter, double-entendre title, Back. Moehringer, a writing polymath, helped Andre Agassi, as a newly retired tennis player, write his memoir, Open, another excellent, four-letter, double-entendre title. It would be hard to imagine Moehringer working with a subject who is not committed to saying something new and and insightful. Agassi called Moehringer after reading his beautiful memoir, The Tender Bar, asking Moehringer to help him with his memoir. Moehringer, a workaday newspaper reporter then, repeatedly declined, until he became convinced of Agassi’s commitment to candor.

Retirement was a pathway to candor for Agassi and looming semi-retirement may loosen Woods in a similar way, or so his publisher might bet and the reading public might hope. Woods would not be bothering to write a book if this were a quick cash grab. The 1997 Masters: My Story, despite some interesting passages, lacked depth, breadth, candor and passion, at least for this reader. It did not sell well and had no cultural impact, not in golf and certainly not beyond.

There would be no point in Woods going down that road again, and no publisher would pay him a serious amount of money to write such a book. The book about the 1997 Masters was written in a difficult period in Woods’s life, with his back often out and his future in the game impossible to predict. Of course, Tiger is often impossible to predict.

ADVERTISEMENT

In Back, Tiger’s motivation will be to tell readers, his daughter and son chief among them, the story of his life that is different from the Tiger Woods life story that unfolds in Tiger Woods, a thorough, excellent and semi-depressing 467-page biography by Jeff Benedict and Armen Keteyian, published in 2018 by Simon & Schuster. (I am writing a Tiger book now for a S&S imprint, and it will not be 467 pages.)

Tiger will try to regain control of his own narrative, one that will stick to him, he’ll hope, for the rest of his life. He knows not many people read books, but that doesn’t stop a book’s message from reaching millions of people. Nothing Woods has ever said makes you think that books and book-reading are important to him, but he can go on Jimmy Fallon and tell the story of the book’s story, and that’s meaningful.

So the stakes are high here. This book can and should be great but will be only if Woods is committed to writing something meaningful, believable and fresh. “This memoir is the first and only account directly from Woods, with the full cooperation of his friends, family, and inner circle,” the press release about Back notes. It uses the present tense, as if the book already exists. That’s interesting and a little odd. It makes you sit up. Good writing does.

The guess about Moehringer is based primarily on these factoids:

*He’s married to the woman, Shannon Welch, who will edit Back;

*He worked with Phil Knight on his memoir, Shoe Dog, which was also edited by Welch.

*The Agassi book is one of the best athlete memoirs ever written;

*The Knight book is one of the bestselling business-mogul memoirs ever published;

*Knight is one of Woods’s closest advisors.

Welch is an editor at HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins. (Both Welch and a publicist at HarperOne did not immediately respond to a request for comment by email on Friday.) Knight, the co-founder of Nike, was the first person to make Tiger Woods a millionaire many times over.

Good rapport between a ghostwriter and author is useful if not necessary, and you could see how there would be good chemistry between Moehringer and Woods. It would have nothing to do with golf and everything to do with tennis. For starters, Moehringer has a keen understanding of one of the great tennis players ever, and Woods has a keen interest in tennis. That was made obvious again this year at the U.S. Open, when he watched Serena Williams and Rafael Nadal with such intensity, his son and girlfriend beside him.

Because of his relationship with Agassi, Moehringer would have an intimate understanding of life its own self that would be meaningful to Woods. For example, the pressures that come with being a dominating figure in your sport, and living up to the expectations of a certain image. The challenges of raising children as an athlete often on the move. (Like Woods, Agassi has two children, a boy and girl, close in age.) Both Agassi and Woods have had lower-back issues that have left them in debilitating pain. Like Woods, Agassi got started in his sport as a toddler, with a big-personality father orchestrating his every move. In their philanthropic lives, both Woods and Agassi have shown sustained dedication to education.

Moehringer conducted 250 hours of interviews with Agassi as the basis for Open; there’s an element of psychotherapy in such a relationship. Woods, like Agassi, has a phenomenal memory. Whether he can be introspective, as Agassi is in his book, is something one can’t know now. That will make or break the book.

“A lot of the things that have been said about me aren’t true, and a lot of the things I used to say about myself aren’t true. Part of my story is something I’m ashamed of,” Agassi told a reporter for The New York Times, when his book came out a decade ago.

Woods sounded a similar note in this week’s press release. He said, “I’ve been in the spotlight for a long time, and because of that, there have been books and articles and TV shows about me, most filled with errors, speculative and wrong.”

It’s a mean-spirited comment to make when you consider the thousands of stories written by the main beat writers who have covered Woods over the years, including Cliff Brown and Karen Crouse of The New York Times, Doug Ferguson of the AP, Bob Harig of ESPN and Steve DiMeglio of USA Today. You’d be hard-pressed to find even a single story by any of those reporters that is “filled with errors, speculative and wrong.” Having said that, there are surely many stories about Woods that are filled with errors, speculative and wrong. (This one could be one of them!) But most? Woods’s use of the word “most” is provocative, willfully so, even if it is obviously inaccurate. Well, Agassi’s book is provocative, too.

When Woods reclaimed his standing as the No. 1 player in the world in 2013, Nike released an ad that seemed to quote Woods. The ad copy read, “Winning takes care of everything.” In quotes, with a photo of Woods. That, of course, was a naked attempt at provocation, in the interest of sales. Now, in Back, Woods will have the chance to say something meaningful and ideally truthful, in addition to being provocative. Does winning really take care of everything? It couldn’t possibly. Agassi says that, in the middle of Open, when he describes (in the present tense) winning his first grand-slam title, at Wimbledon: “But I don’t feel that Wimbledon has changed me. I feel, in fact, as if I’ve been let in on a dirty little secret: winning changes nothing.”

Now that can’t be entirely true, either. Winning on that level changes things. Your bank account, your fame, the expectations on you and within yourself, for starters. But it is an interesting sentence, the one Agassi wrote there, and it is the sort of thing you can write when you’re no longer trying to win.

In 2010, the writer Rick Reilly did an onstage interview with Agassi that included this exchange, cited here for its potential application to Woods’s path. Reilly asked, “Do you feel relief, finally being known?”

“I feel relief knowing that I understand better who I am,” Agassi said.

Michael Bamberger may be reached at Michael_Bamberger@golf.com.

ADVERTISEMENT