Charlie Sifford and Charlie Owens were strong, athletic, proud black men with impressive mustaches and cigars underneath them. Both also played excellent golf with bad legs. They found it amusing (but only to a point) that they were sometimes confused for one another. They were both important figures in the professional game, but for totally different reasons.

From the late 1950s on, Sifford was widely known as golf’s Jackie Robinson, and Tiger Woods noted with sorrow the 2015 death of the man he called “Grandpa Charlie.” Owens, who died Sept. 7, certainly faced racial discrimination, but that wasn’t his life’s work. In acts that were rooted in golfing self-preservation, he became an important figure in the effort to make golf more playable for more people, including those who struggled with walking, as he did, and who struggled with the yips. He had that going against him, too. Plus an eye condition.

Owens won with a long putter decades before Adam Scott did, fought to play golf out of a cart decades before Casey Martin did, played golf with sunglasses on decades before David Duval did. Owens was a man, born dirt-poor and educated by the U.S. Army, who thought for himself.

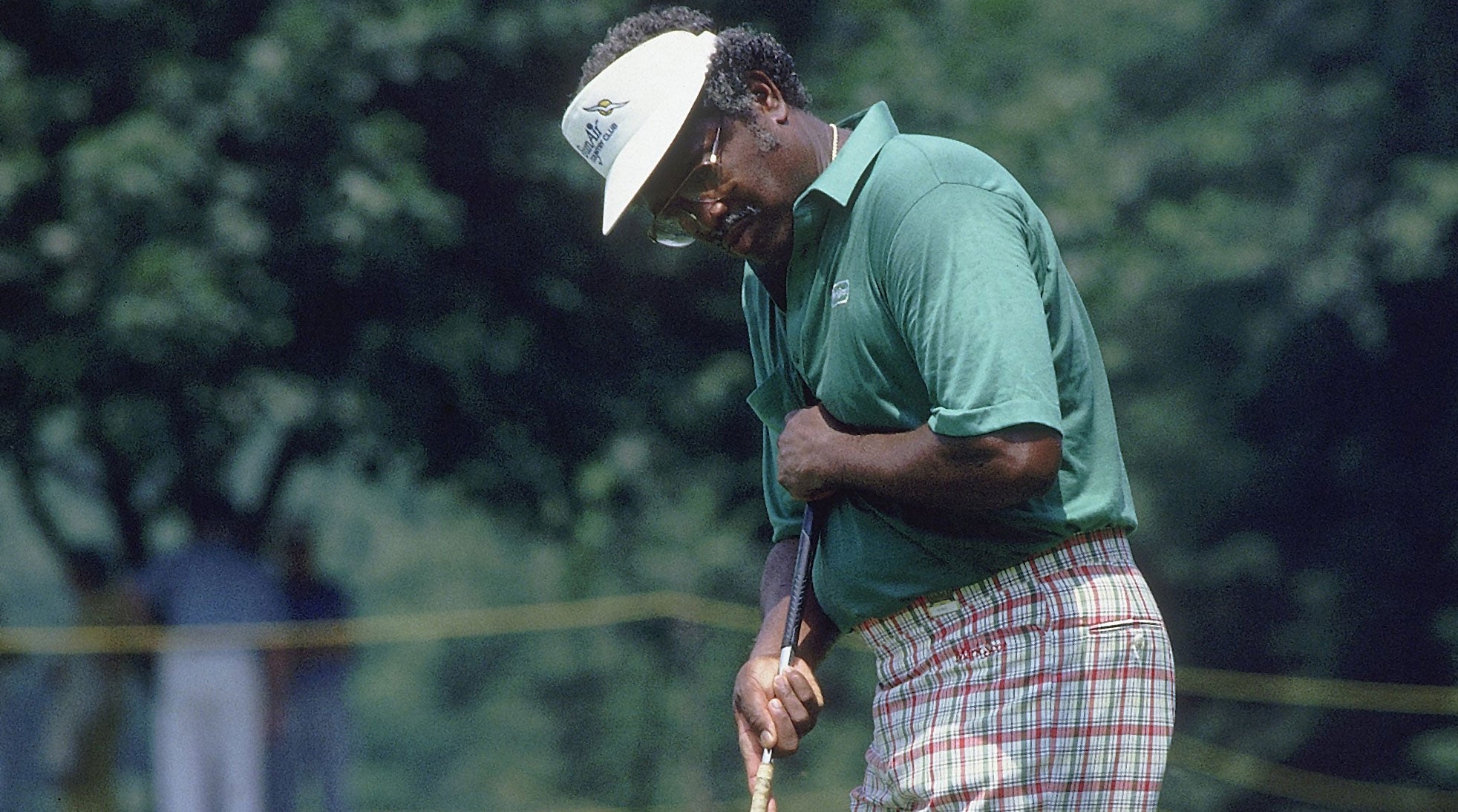

On Feb. 9, 1986, Owens, two or three inches over six feet, became the first pro to win a prominent event—the Treasure Coast Classic, a senior tour event—with a long putter, a 52-inch model he had made himself, held with the left hand held against his chest with the right hand swinging freely. Golf took notice. (Arnold Palmer, Gary Player, Billy Casper and Chi Chi Rodriquez were all playing the senior tour on a regular basis then.) Owens was not the inventor of the long putter, but in his mind he was. He came up with the idea for the putter, and built his own, without knowing what his inventive forebears had done.

“I thought I could come up with something that looked good and was the right weight, so I would have only one hand to deal with, my right hand,” Owens told Bill Fields of Golf Digest 10 years ago. “The heavier they got, the better they felt, but I couldn’t get one heavy enough. I had control of the yips, but I had to hit it too hard on long putts. I had a friend who was a machinist and took it to him with a blueprint of the way I wanted it to look. He cut the shape I wanted, which was almost like a flying saucer with a square face. That thing was so ugly.”

But nobody every said a putter had to be beautiful. (Have you watched any golf on Tour this year?) Long putters have been very effective for some players, including Adam Scott, who won the 2013 Masters with one. In the early years of the long putter, the USGA was not worried about it. It seemed like a novelty that would never catch on. In 1989, the USGA said that long putters were “not detrimental to the game. In fact, they may enable some people to play who may not otherwise be able to do so.”

But by 2012, that viewed had changed. Guan Tianlang, a 14-year-old Chinese golfer, won the Asia-Pacific Amateur Championship with a long putter, its butt end lodged in his stomach, the same type of putter and method used by Ernie Els, who was battling the yips. The USGA did not like what it saw. By 2016, long putters were still allowed, but you couldn’t use them as Els and Sifford did—you could no longer anchor the butt end of it against your body. Palmer was a prominent voice in support of the USGA’s position. He felt golf shots should be played with the hands together, in a free-swinging motion.

Owens was long done playing tournament golf by then. He walked with an obvious limp and a stiff left leg, the result of an ankle injury he suffered as a paratrooper in Fort Bragg in 1952. He had three knee operations on his right knee.

Owens played in 46 PGA Tour events between 1971 and 1980, and he made the cut in 21 of them. It was an era when there were far more African American golfers on Tour than there are now, but it was a much more difficult way to make a steady living. But walking was arduous for him and when he got on the senior tour in 1983 he could play out of a cart. That made all the difference. He won twice on the senior tour, both times in 1986. He protested against the USGA in 1987 when the governing body would not allow the use of carts at the U.S. Senior Open. He said then, “The only reason I’m really here is to see if we can get this rule against carts abolished.” Owens shot a first-round 77 at Brooklawn Country Club and withdrew.

Owens grew up in a shack on a golf course in Winter Haven, Fla., where his father worked. Describing his childhood to Tom Boswell of the Washington Post years ago, Owens said, “Golf clubs were my toys.” Owens is a member of the Florida Sports Hall of Fame and the African American Golfers Hall of Fame. Sifford wrote a landmark book called “Just Let Me Play.” Owens could have written a book called “I’ll Figure It Out.” Owens had en eye disease called iritis, which made his vision blurry. When the drops prescribed to address it became too expensive, he started using herbal tea instead, and it helped, as did the sunglasses.

Owens was an elegant dresser but his golf was far more inventive than elegant. He played his entire career cross-handed. It is a grip was once fairly common, especially among rural, self-taught golfers. Now it is nearly extinct, although Oklahoma has recruited a cross-handed golfer for its team, Patrick Welsh.

Between the eye drops and sunglasses, the cart, the long putter and the self-taught, cross-handed game, you had in Owens a golfer the likes of whom the game will never see again. He once called the long putter he made “a vision of God.” He went to his maker at least knowing the putter itself was legal for play. Just don’t put that top hand against your chest.

But as golf says farewell to Owens, his link to Sifford’s important legacy should not be lost. He once told the late golf historian Rhonda Glenn about an incident that happened to him at a senior event in the 1990s. He was driving a courtesy car and a man said to him, “Boy, who you driving this car for?” Owens’ response should be remembered:

“Number one, I’m not a black boy. Number two, I am a black player playing in this golf tournament. I’ve been told to drive this car.”

Michael Bamberger may be reached at mbamberger0224@aol.com.