LIV Golf’s format was his idea. Now? He wants to save the PGA Tour

The PGA Tour's position atop the professional game suddenly feels more precarious.

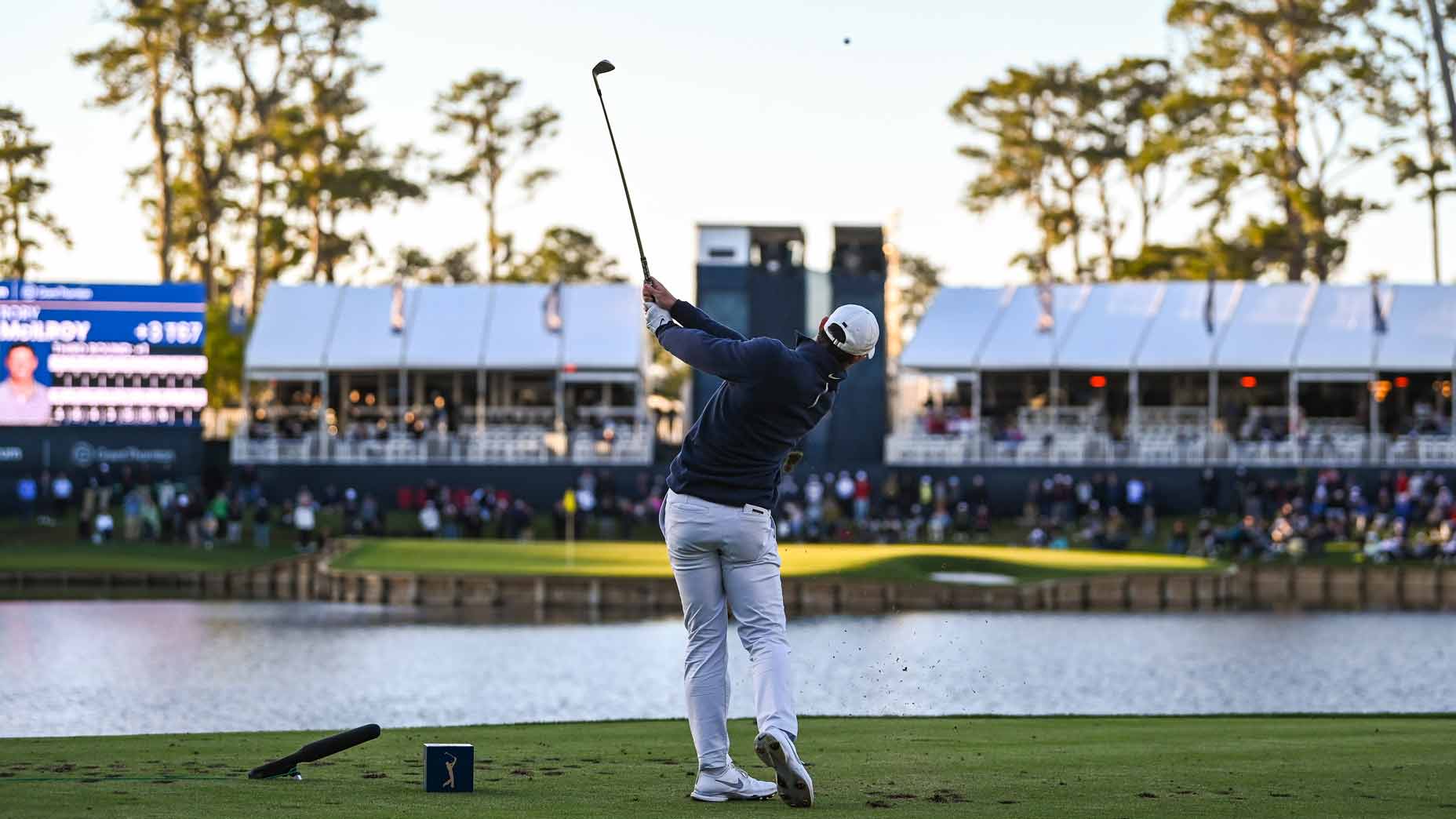

Getty Images

Andy Gardiner insists he isn’t jealous.

But you wouldn’t blame him if he was. On Thursday, a new vision for men’s professional golf began streaming to the masses. Fifty-four holes. Shotgun starts. A parallel team competition. Microphones everywhere, bringing you inside access. This was Gardiner’s vision, coming to life.

“Bizarrely, there’s a sense of pride,” he says. “I’m talking about something that I wrote. I just get to see somebody else hopefully deliver it in half-decent fashion.”

Gardiner is sitting at his office desk in London. Eric Clapton adorns the wall beside him. (“My oldest, longest musical love,” he says.) A movie poster hangs behind him: Pale Rider. Gardiner asks if I’ve seen it. I have to look it up: It’s an ’80s western starring Clint Eastwood, a ghostlike cowboy who appears from nowhere to save a small California mining town. I wonder if Gardiner sees some cowboy in his current venture.

He won’t be on the ground at this week’s LIV event at the nearby Centurion Club; there are a few people attending he has no interest in bumping into. But his people will, studying its successes and failures. Gardiner will be paying close attention, given he’s the CEO of a different would-be golf league — one that, so far, consists of zero players. But now that its greatest threat is a reality, seizing big-name pros, Gardiner thinks there’s something he can do for the PGA Tour:

Save it.

You could make the case that this makes Gardiner the most optimistic man in sport. He wrote his first plan to revolutionize professional golf in 2010. Held his first player conversations in 2013. Turned it to a full-time venture in 2018. The Saudis were part of the plan for a while, he says. But then each group went its separate way. The Saudi group has arrived at its intended destination first; opening tee shots Thursday marked the beginning of LIV, a breakaway golf league that already includes Phil Mickelson, Dustin Johnson, Bryson DeChambeau and, well, you’ve seen the names by now. Gardiner’s been at this for a decade, maybe more. And still, no players. You may have already read about Gardiner and the Premier Golf League. You may have written it off as dead in the water. But despite all of the above, Gardiner says he feels no envy for LIV’s position.

“None whatsoever,” he says. “The activities of LIV don’t reduce the chances of our proposals being implemented. I actually see them probably enhancing these chances. We’ll see.”

The PGL Vision

We’ll see. Gardiner, a 49-year-old former corporate finance lawyer, has gotten this far by selling his PGL vision to people like myself, who see a sparkly idea and back-of-the-napkin math, hear the reasoning behind his estimated valuation — 10 billion dollars — and think, y’know, that actually makes a lot of sense.

His proposal has plenty in common with LIV’s series: 18 events, 12 teams, a PGL Team Championship with a $20 million prize on the line. The biggest difference is in financial structure. Where LIV is owned and funded by the Saudi Public Investment Fund, the proposed PGL (and its estimated $10 billion in equity) would be a new for-profit corporation owned by the players and endorsed by the PGA Tour. Fifty percent would go to PGA Tour pros, while Korn Ferry and DP World Tour pros would split an additional 10 percent. The rest would go to commercial partners, directors, investors and the PGL’s foundation.

His argument is not made on moral grounds. Much of the scrutiny on LIV’s model has been the controversial source of its funding, but Gardiner rejects that as a point of differentiation.

“I think that this is purely economic,” he says. “Early in Covid, we were confined to home. And I had this eureka moment thinking about who should own this. It’s the players, and, ultimately, it’s the fans, too.”

Gardiner’s vision includes listing the PGL on NASDAQ, giving fans the opportunity to buy in. But in the early days he’d incentivize players to get on board by front-loading their equity payments: roughly $2 million up front for PGA Tour voting members, $300,000 for Korn Ferry Tour members. (They’d eventually divvy up $6 billion in shares over 10 years, theoretically.)

The other key difference comes from team construction. While LIV teams are thus far “captained” by one player and drafted every week, the entire enterprise remains owned by the league’s investors and thus the PIF. Under the PGL proposal, each team would become a franchise. Gardiner has been in touch with potential team owners and expects that, should the PGA Tour buy in, there would be a significant bidding war to snag one of 12 coveted slots. He says a conservative estimate would put each franchise at $500 million.

If any of the above numbers sound outlandish, that’s fine. One key phrase — should the PGA Tour buy in — is a massive question mark. But Gardiner’s vision serves as a lens through which we can see the PGA Tour’s current position.

The PGA Tour’s big problem

The first dominos fell on Thursday morning, when several PGA Tour players — Johnson and Mickelson among them — hit the first shots of their LIV careers. The Tour responded with sanctions against those players, suspending them indefinitely. It’s not clear they’ll have much effect. The Tour is essentially firing pros who have already quit. After all, the players who have left sound at peace with never again teeing it up under the FedEx Cup banner.

“Obviously at this time it’s hard to speak on what the consequences will be, but for right now, I resigned my membership from the Tour,” Dustin Johnson said matter-of-factly on Tuesday. “I’m going to play here for now, and that’s the plan.”

More players are expected to leave the PGA Tour for LIV, chasing the types of deals signed by Johnson and DeChambeau, whose negotiations came together quickly and involved nine-figure sums that the Saudis seemingly magicked out of nowhere. That sort of financing is tough to compete with. Scratch that — it’s impossible to compete with.

It’s worth focusing on that point. The Saudi-backed LIV league exists because it has the money to exist. This series has been able to overpay for a number of big-name Tour pros because they have the funds to do so without, as best we can tell, any expectation of financial return. Without that funding, none of this would happen. Even with that funding, LIV’s position was precarious as recently as February, when Mickelson’s comments sent him — and the league — into hiding. That feels like a long time ago.

So that’s the PGA Tour’s first problem: Some of its big-name players are leaving, and there’s no way to compete with the money they’re being given.

Its other problem, Gardiner argues, is a watered-down schedule that features too many events, dividing fan attention and lessening its overall product.

“The problem is that a field that has 11 of the top 50 is deemed to be ‘strong,'” he says, approximating the makeup of this week’s RBC Canadian Open. “Whereas if you follow the logic of every other major sport in the world, your strength of field would be 50 of the top 50 because that is the best product that can be produced.”

The proposed solution

“The likelihood of golf fans tuning in to watch the top 50 play 18 times is, I think, incredibly strong,” Gardiner says.

His vision would involve integrating the PGL into the current PGA Tour schedule. Some existing events would be elevated, combining their history, legacy and familiarity with a new format and an influx of cash and attention. Other events would run worldwide. A half-dozen would stay at the same course every year, while the others would rotate. Courses and countries would pay for the Tour to come through, Gardiner says, just like they pay tens of millions for Formula 1 races to come to town.

The PGL events plus the majors would make up a robust 22-event schedule; top pros could play additional events if they so chose, but fans would know which events would boast the biggest fields.

If that sounds like a massive departure from the current model, that’s the point, Gardiner says.

“I’ve been reading Twitter, which is not something I tend to like doing on a regular basis, but I find myself drawn to it because you’re also getting the comments from fans about the format and the idea,” he says. “Some people just say, ‘Oh, the team stuff sucks and it’s all a load of rubbish,’ but they are a minority. I think there are far more people who are true fans of the sport who are prepared to say, ‘Well, let’s have a look at it.’

“LIV’s next three days will accelerate that conversation. When they play in America it will be another gear shift. Is the field getting stronger, in all likelihood? Yes. And now they’ll be in the backyard of the PGA Tour.”

Change is difficult, particularly without accelerants like blank checks. Gardiner knows that well. He still can’t get a meeting with PGA Tour commissioner Jay Monahan, despite years of lobbying to do so. A Tour-commissioned evaluation of the PGL plan cast doubt on its financials. But Gardiner argues the auditors never spoke to him and didn’t have a proper understanding of its inputs.

Initially his focus was on convincing the top dogs. That has shifted; he’s talking to every Tour player he can get a hold of, now. Get enough rabble-rousers and the Tour will be obligated to more thoroughly evaluate the plan. Once that door opens, Gardiner says, he doesn’t think it can be closed.

He’s noticed a sea change in recent weeks: Agents are reaching out to him rather than the other way around.

“I’ve had numerous calls from people in the last 24, 48 hours just basically saying, ‘What are they planning? Why won’t they talk to you?’ And these are people who are meaningful individuals within the game. It gets to a point where it becomes baffling as to why they wouldn’t have that conversation,” Gardiner says.

In his mind, there are three models currently in play.

There’s the PGA Tour model, which he says “is not delivering all that golf can deliver for fans, sponsors and broadcasters.” Now that the Tour has shown its vulnerability, its future seems suddenly less certain.

“We’ve seen it’s not infallible,” Gardiner says. “The genie is out of the bottle. The change has occurred.”

Next you have the LIV model, which involves large amounts of money paid to a relatively small number of players. Those players won’t receive any ownership stake, so they’re beholden to those funding the league. But in Gardiner’s mind, LIV is “demonstrating a format that, done well, is the best we believe golf can be.”

That leaves the PGL’s proposed model, which follows a similar format but gives ownership to the players and a handful of other stakeholders.

“If you come to the conclusion that the status quo will not prevail, that change has occurred, is occurring and will continue to occur, the question then becomes who gets to own it?” Gardiner asks. “We think that should be decided by the membership. We’re not far from having the critical mass that is required for that conversation to take place. We’re not far now.”

It’s possible the PGA Tour has something up its sleeve, another card to play that would meaningfully change the narrative around its departing players. It’s possible they’re hoping to just supplement the status quo with Fall Series big-money add-ons and PIP prizes and rely on its legacy and its television product. But after years of rumors, LIV’s arrival makes it clear that the Tour’s status quo isn’t necessarily a safe place to be. Now what?

Gardiner may not be Clint Eastwood. But he’s riding into town, hoping there’s a second life for his vision after all.