Johnny Ruiz is a young touring pro from Southern California patiently playing his way through golf’s minor leagues — the Canadian tour last year and the Web.com in 2018. Anonymity is part of the deal on these circuits, with sparse galleries and minimal media coverage. But Ruiz has discovered that wherever he goes a very specific kind of fan finds him. “Last year, my caddie and I always laughed about it,” says Ruiz, “because at every single tournament someone would send me a message saying, ‘I’ve been watching your swing on Instagram for so long, can you grab me a ticket so I can see it in person?'”

Things got more intense when he qualified for the 2017 Canadian Open on the PGA Tour. His swing coach of five years flew north to caddie for Ruiz, and they were serenaded throughout the week. “On almost every hole,” he says, “people were yelling out George’s name. It was kind of crazy — he was getting more love than most of the actual players.”

The guru in question is George Gankas, who inspires in his followers a fervor reserved for religious revivals. Gankas has more than 100,000 disciples on Instagram (@georgegankasgolf), and dozens of top young players treat his riffs as holy scripture. They flock to him because his ideas are at once simple and radical, and he preaches speed above all else. No one on the PGA Tour averages as much as 125 miles per hour of clubhead speed with their driver. (Dustin Johnson clocks in at 121.) Gankas has 20 players in his stable of collegians and mini-tour warriors swinging it 130 mph or above. But his appeal transcends mere mechanics.

Gankas, 47, is the quintessence of California cool, usually teaching in flip-flops and baggy shorts. His patois is cribbed from both hip-hop and surf culture. His pupils are addressed as bro or dude, even if they’re female. They don’t have discussions about swing theory — they rap it out. Good strikes are celebrated as dope, mint or Purina. Make a particularly good swing and you might earn the ultimate honorific: That’s sick. Gankas’s unassuming vibe is reflected in his home base: Westlake Golf Course, a scruffy public track 30 miles north of Los Angeles. The hitting area is mats-only, but thanks to the countless videos Gankas has uploaded to YouTube and social-media channels, it has become some of golf’s most hallowed ground. Says Gankas, “This happens over and over: People show up here for the first time and they stop in their tracks and say, ‘Man, this is exactly how it looks on the ’Gram.’”

Gankas has built his audience and his business — he charges $350 an hour and is booked out months in advance — with a tech-savvy willingness to put his ideas on display for the world to see. But his primary product is passion. No one believes more in what they’re teaching or imparts it with more gusto. “He is a golf tragic,” says 13-time Tour winner Adam Scott. “He loves the golf swing. Although he has that California vibe and seems a little out there for the traditional golfer, he has spent 20 years just looking at and thinking about the golf swing, and he knows a hell of a lot.”

Scott, like many others, found Gankas through YouTube videos, and was so intrigued that he rang him up in February 2018 so they could work together. Scott immediately incorporated a new posture at address and a variety of other tweaks. Gankas rarely travels on Tour, so by the summer Scott had gone back to his old coach Brad Malone, but the 2013 Masters champ says Gankas “steered me in the right direction — I firmly believe that.” After a couple of years in the abyss, Scott reemerged at the 2018 PGA Championship, which he should have won but for a handful of missed short putts on the weekend. Padraig Harrington, one of golf’s most beautiful minds, continues to work with Gankas. So does Oklahoma State’s Matt Wolff, whose wonderfully quirky swing was the talk of the 2018 NCAAs even before he holed a putt to win the national championship for the Cowboys. Gankas also advises young studs Braden Thornberry of Ole Miss, the top-ranked amateur in the world; Akshay Bhatia, the top-ranked junior; and Bobby Holden, the Div. III NCAA champ. Seemingly every day another talented prospect or aimless Tour player reaches out for counsel. “It’s getting really crazy, bro,” he says.

And very soon the brand will expand even further. After a dispute with a former business partner forced him to reorganize, Gankas is about to launch a groundbreaking website for the golf space. Instead of continuing to give away his teachings for free on the Internet, he is going to a subscription-based model in which his diehards will have unlimited access to countless hours of new videos, for around $30 a month. It will be a highly customizable experience in which subscribers can search for specific drills and/or have instruction delivered for their particular swing or tendencies. Gankas is considering offering, for an additional fee, personalized video lessons, and he is training certified deputies to help keep up with what will surely be the heavy demand. With this cult hero on the cusp of mainstream stardom, some basic questions need to be answered: Who exactly is George Gankas? What does he believe in? And is he the flat-brimmed, jive-talking future of golf instruction?

* * * * *

Gankas grew up in a testosterone-fueled home in Santa Barbara, Calif. His father, Frank, was a competitive bodybuilder, and so was his stepmom, Nikki. “She was even gnarlier than he was,” Gankas says with a laugh. He gravitated toward macho sports like football and wrestling. Gankas considered golf the province of “weenies” and didn’t try it until late in his senior year of high school, after making it to the state tournament in wrestling. He was instantly hooked. His love for the game became a kind of zealotry, and within a year he was shooting around par, good enough to earn a spot on the team at Ventura Community College, which led to a partial scholarship to Cal State Northridge.

Gankas was entranced by golf’s mind-body connection, so he pursued a degree in psychology; at the same time he approached the swing as if he were a professor in a lab. Each weekend he would tape the Tour telecasts on his VCR, then watch them over and over. “I would slow down every swing and then pause it at impact, trying to guess which way the ball was going,” he says. “I was endlessly watching how the body moved, and what the club did at the bottom of the swing. But it was confusing, because every player did something different. So I had to sort out for myself what really worked.” He plunged deeper, studying the swings of golden oldies like Bobby Jones, Ben Hogan, Sam Snead and Gay Brewer, as well as the action of new-school speed icon Jamie Sadlowski. At nearby Westlake he became friendly with fellow obsessive Chris Como, who’d later earn renown as Tiger Woods’s swing coach. On Como’s advice, Gankas immersed himself in biomechanics and physiology.

Upon graduating, in 1995, Gankas made a go of it on the mini tours. To fund the dream, he caddied at swank Sherwood Country Club, one town over from Westlake Village. Gankas didn’t have much luck playing professionally, but his loops at Sherwood loved his swing tips and encouraged him to give proper lessons. And so he did, suddenly getting an array of supplicants on which to test his theories. For years Gankas bounced around driving ranges until one of his Sherwood loyalists, Janet (Mrs. Wayne) Gretzky, helped him establish a beachhead at Westlake in 2006.

The stodgy world of swing instruction would never be the same.

* * * * *

To spend a day sitting on a bench under an umbrella at the Westlake range is to stumble upon a secret society. Gankas doesn’t teach so much as preside over community gatherings, with various folks hanging out and listening in. Those who take lessons might linger for the rest of the day, intermittently hitting balls and chopping it up with the assembled audience. On this day, Gankas’s lesson sheet included Thomas Bailey, a young pro who had flown from England in part because he credits Gankas with curing his persistent back pain; Annika Pieszankgoss, a 17-year-old who, thanks to Gankas’s enthusiasm, had given up dressage to pursue a college golf scholarship; Tristan Gretzky, Wayne and Janet’s 18-year-old son, who hits it as far as his frequent playing partner, Dustin Johnson; and a freshman at exclusive Oaks Christian High School, whose bejeweled mom dropped him at the range and announced she was repairing to the bar…at 3 p.m.

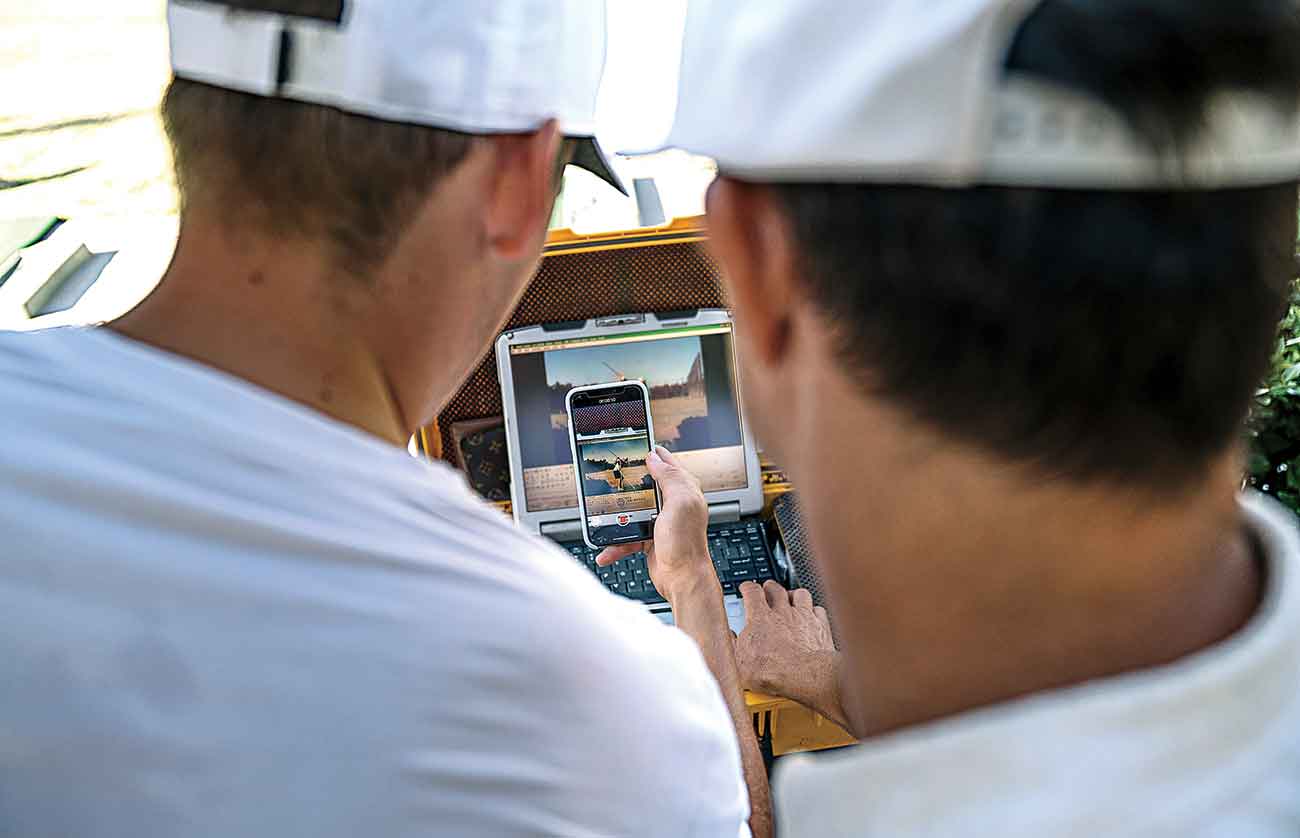

Gankas is literally a hands-on teacher, frequently moving his pupils’ limbs through different positions. Every swing is monitored by a Flightscope launch monitor and a video camera, and Gankas races between his laptop and the mat, instantly processing information and applying it. His patter never stops. He teased Gretzky by saying, “You’re not using your legs, bro. You get one lesson from Butch and all of a sudden you’ve lost 30 yards.” He followed with the ultimate enticement: “Give me a good swing and I’ll put it on the ’Gram.”

Says PGA Tour veteran Parker McLachlin, who began working with Gankas early this year, “I always wonder how he has so much energy. He is en fuego at all times. But it comes down to him being so passionate about helping people. He has so much knowledge he’s eager to share. I’ve always struggled to find a coach who understands me, because I don’t do things traditionally. I went to a lot of big-name instructors, but they seemed more interested in collecting their $1,000-an-hour fee. The first time I met with George he said, ‘Bro, I’ve followed you for years, and I’ve always wanted to give you a lesson.’ For him to be so invested is a pretty amazing feeling.”

Throughout the various lessons, Gankas’s phone never stopped bleating, and he checked every message and took every call, sometimes carrying on three conversations at once — with a student on the phone, with his pupil on the mat and with whomever was seated nearby. Wolff called to check in from his first collegiate event of the season, at Pebble Beach, where he had just opened with a 65. (He’d follow with rounds of 66-68 to win handily.) From Ireland, Harrington was sending a torrent of swing videos to be perused. Gankas’s scheduler checked in about offers for far-flung private lessons. (Clients in New York and Jackson Hole had recently dropped serious coin to fly in Gankas.) His old pal Como wanted to talk through the details of an upcoming joint appearance on Golf Channel.

Gankas worked pretty much from sunrise to sunset, his only break being lunch at a nearby deli with a half-dozen apprentices. He paid for the whole table, as he always does. On the drive home he took a call from Florida State’s Cole Anderson, who was in sixth place midway through the Junior Players but described his action as “wipey.” His shoulders were outracing his hips on the downswing. Gankas diagnosed the problem while roaring around in his Audi A7, and promised to send a video of an impact drill to cure the problem, which he did upon reaching the course.

Gankas has never met Anderson in person. Nor Thornberry. But his ability to demonstrate his own ideas on-camera has helped him connect with them and his legion of electronic constituents. Gankas takes a deep pride in still being able to play at a high level; his current index is +4. A treasured tale in his inner circle is that Sung Kang, a four-time winner in Korea, decided to go forward with a partnership after a get-to-know-you round in which he was beaten straight-up. (With a smile, Gankas offers this non-denial: “I can’t talk about that. I don’t want anyone’s feelings to get hurt.”)

Gankas is toying with the idea of trying to play some Champions tour events when he turns 50. Because he still thinks like a player, he takes a more holistic approach to counseling his charges. “George does a really good job of understanding that golf is an emotional game, a mental game, and that not everything is as black-and-white as the Trackman data,” says McLachlin. “He understands our fears, our tendencies; he understands that stuff changes from driving range to the course, that it changes from Tuesday to Thursday, and it changes again from Thursday to Sunday. When we talk about a particular shot I hit, he’ll ask, ‘What did you do on the previous hole? Where was your head? Was there tension in your arms? How were you breathing?’ Most coaches look strictly at mechanics. S—, anybody can do that.”

* * * * *

Though Gankas has a core of bedrock tenets, flexibility is the hallmark of his teaching. “Every swing is different,” he says. “Everybody is built differently. For me to try to put all people into one little box would be an ego thing. You can hold the club however you want. You can take it back however you want — down the line, laid-off, crossed-up, I’m down with all of it. The key is matching up tendencies. If you do ‘x,’ then you gotta do ‘y’ to get back to a Hall-of-Fame impact position.”

Wolff is a case in point. He was a serious jock growing up: quarterback, shortstop, shooting guard. His golf swing always had a ton of speed but very few traditional moves. “The teachers who wanted to work with me,” Wolff says, “all said the same thing: ‘I can make you a really good player.’ They all wanted to ‘fix’ me. It made me doubt my abilities. The first time I met George [at age 14], he said, ‘I love your move, don’t ever let anyone screw with it.’ He told me I could be the best player in the world. I couldn’t even really process that because my whole life I was told I had to change.”

Together they have perfected the most mind-blowing swing in big-time golf. On the way back, Wolff gets up on the toe of his left foot like a baseball slugger. At the top, the club is not parallel but waving at the sky and so far across the line that it’s pointing 45 degrees right of the target. But what follows is pure, blurry poetry. Wolff’s high-profile success has led to the misconception that Gankas is a mad-scientist cooking up crazy swings, but the opposite is true: He’s an open-minded pragmatist working with what he’s given. Arron Oberholser, the former Tour player and now Golf Channel analyst, recently visited Gankas to see what all the buzz is about. “I picked up 5 miles per hour in literally three swings,” he says. McLachlin adds, “I’ve seen him take weekend hackers and get them 10 more miles per hour in one lesson, which is crazy.”

Gankas’s belief that he can improve anyone/anywhere is at the heart of his new business model. As much as he loves holding court at Westlake, there is only so much of him to go around. “What about the kid in China or India who wants to tap into what we’re doing?” he asks. “What about the kid in North Dakota? I like helping people, and I want to reach as many as I can.”

Revolution Golf, a slick operation funded by cable behemoth Comcast by way of Golf Channel, has signed Como and a host of other big-name instructors in an attempt to take golf instruction deeper into the digital world. Gankas’s is more of a grassroots movement, and if he can capture a large audience it might ultimately lead to a revolution in which high-level golf instruction becomes more democratic.

“You definitely feel special getting to work with George, now that he’s so Instragram-famous,” says Bhatia, who has won a number of top junior events in the last year. “How cool would it be if people everywhere could benefit from his knowledge? I’ve heard George talk about how much he wants to change the game. I’d be surprised if he doesn’t.”