How this Bobby Jones descendant is using golf to help promote mental health

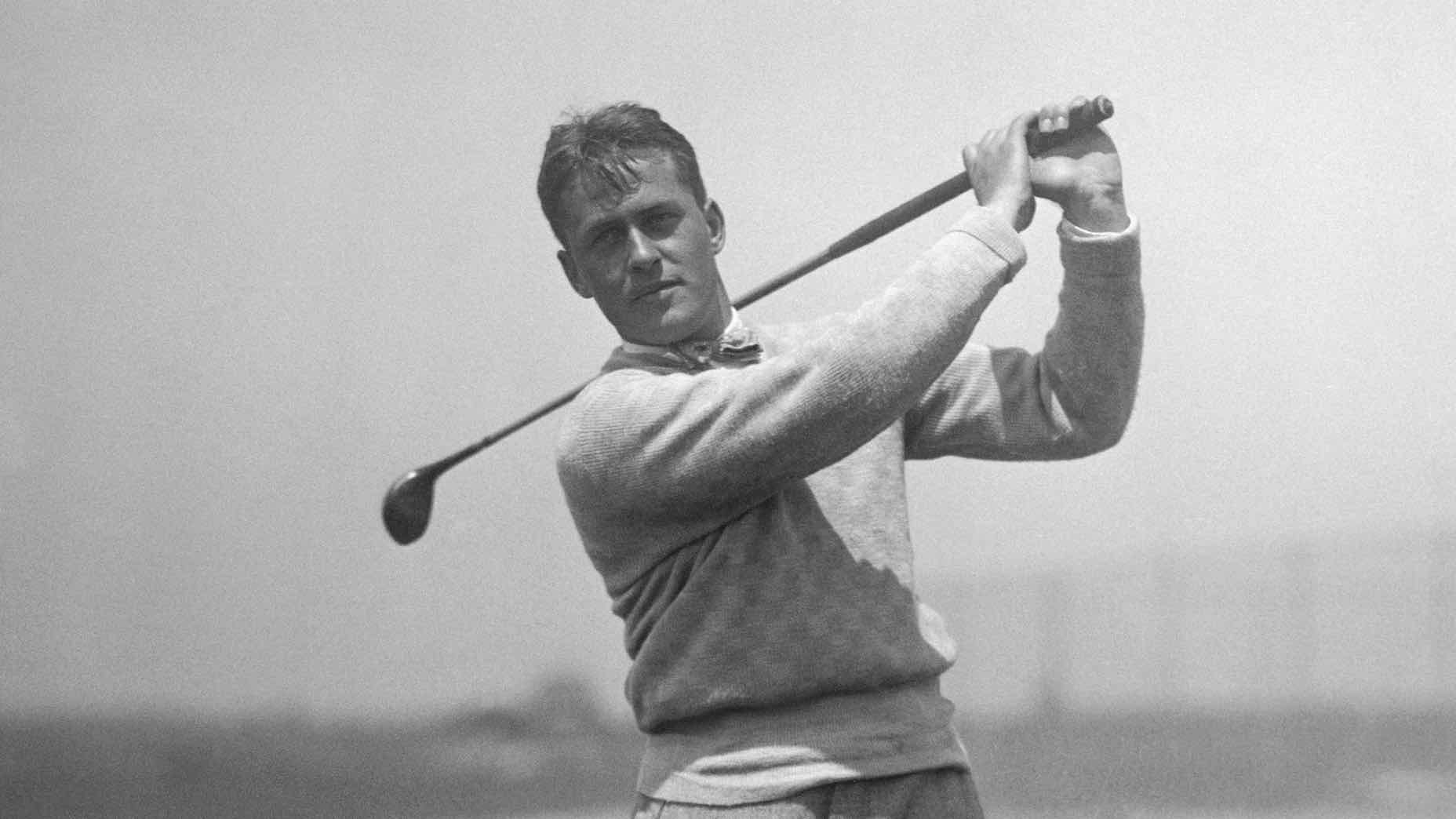

Robert Jones Black beneath a portrait of his great-grandfather, Bobby Jones.

courtesy generation next

As the most decorated amateur golfer of all time, Bobby Jones played a game with which most people are unfamiliar.

He also faced struggles with which nearly everybody can relate.

In 1930, fresh off a Grand Slam-winning season, Jones, then 28, hung up his spikes, quit competing, his body more than able but his mind no longer willing. He found tournament golf stressful. It took everything he had, creating pressures that he likened to being “in a cage.”

“There are two sides to the story of Bobby Jones,” says his great-grandson Robert Jones Black. “One was his success on the course. The other was his intellect and emotional intelligence, and the way he dealt openly with his mental health.”

Mental health. It’s a hot-button topic, far more now than it was in Jones’ day.

In golf. At work. And most places in between.

Name the source of stress. The virus. Online venom.

Almost no one is immune.

Black, who is 46 and earns his keep as a sports marketer, has founded a non-profit to help address these problems, an organization that draws on the legacy of Bobby Jones while promoting the values that he embodied.

It’s called the Generation Next Project, and its efforts are focused on a demographic that is often most afflicted by the pressures of our age but also least equipped to cope with them.

Generation Next is all about the mental health of kids.

“When you think about what kids are dealing with today with technology and social media, and then you throw the pandemic on top of it all,” Black says. “They’ve been facing isolation and uncertainties on a scale that you and I never did.”

In response, Generation Next works on multiple fronts. Through fundraising events and private donations, it provides financial support to two non-profits: the American Junior Golf Association and the Positivity Project, a social and emotional curriculum designed to encourage positive traits such as empathy, self-awareness and confidence among the pre-K-through-12-grade population. At the same time, Generation Next creates digital content to help kids and their families identify mental health problems while providing tools and resources to help address them.

Next year, Black and his colleagues plan to launch a series of golf retreats, allowing teens and their parents to escape for two-day, three-night instructional experiences hosted by a golf celebrity.

While Black is quick to concede that golf can’t be a cure-all, he’s certain it can be of great assistance.

“I’ll never be able to say to everybody that it is going to be the solution to every problem,” he says. “But the golf community is influential. And the sport itself, whether you’re talking about the values it cultivates or just the simple benefits of getting out in the fresh air, is an incredible illustration of the positive impact you can have on the social and emotional development of kids.”

Like many rays of light, Generation Next was born in darkness. In April 2020, shortly after lockdowns started, the young son of Black’s friend and business partner committed suicide. Twelve-year-old Hayden Hunstable had no history of depression or other mental health issues. But in the isolation of the pandemic, his routine disrupted, many his favorite activities canceled, he had turned increasingly to online gaming. His parents attributed his suffering to what they described as a “perfect storm.”

The tragedy, while unique, rang out as a red alert to a larger problem.

“Even before we all started to feel the full impact of the pandemic, all the experts were saying that there was going to be a tsunami of mental health issues on top of an already volatile environment for kids,” Black says. “And then the tsunami hit, and we were at ground zero.”

In the wake of Hayden’s death, his father, Brad Hunstable, founded Hayden’s Corner, an organization aimed at educating kids and parents about responsible gaming while pushing for federal legislation that would require that resilience classes be included in the core curriculum of K-12 schools nationwide.

If ever there was a time to embrace [the Jones] lineage, the time was now.

It dawned quickly on Black that he wanted to do more than mourn beside his friend.

“My family and I have always tried to be humble about our connection to this very important figure in golf,” he says. “But if ever there was a time to embrace that lineage, the time was now.”

Not only does the Jones legacy give Black leverage in the golf world, but it also provides him with inspiration. Among his other talents, the greatest amateur ever had a gift for crystallizing words into wisdom. His Bartlett’s-worthy quotes are legion. One of many posted on the Generation Next website reads: “Golf is the closest game to the game we call life. You get bad breaks from good shots; you get good breaks from bad shots — but you have to play the ball where it lies.”

Off the course, though, you’re allowed to make improvements. That’s what Black is after. Next year, Generation Next plans to ramp up its charitable efforts, backed by three major fundraisers, each tied to a big-time golf event: the Tour Championship, at East Lake, in Georgia; the Presidents Cup, at Quail Hollow, in North Carolina; and the U.S. Open at The Country Club, near Boston. A percentage of every dollar raised through those and other efforts will go toward producing additional content, which, Black says, will be distributed on digital platforms that maximize reach: a widespread message to address a widespread problem.

“In golf,” reads another Jones quote on the Generation Next website, “the most important distance is the five inches between the ears.”

That’s true in life, too.