What happens when a golf course’s most precious resource grows sparse?

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Email

The future of golf in America depends on responsible stewardship of our most important resource: water.

Jeff Mangiat

This content was first published in Golf Journal, a quarterly print publication exclusively for USGA Members. To be among the first to receive Golf Journal and to learn how you can ensure a strong future for the game, become a USGA Member today.

SUSTAINABILITY AND WATER conservation have become hot topics in recent years, and it’s easy to see why.

According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), between the years 2000 and 2020, as much as 70 percent of the United States experienced abnormally dry conditions. Coupled with a rise in the Earth’s average temperature, that has created an alarming paradox: the rate of evaporation from soil and transpiration from plants has increased, making more water available in the air for precipitation, but, in some areas, the land continues to get steadily drier. As a result, the EPA predicts that historically wet areas of the country will get wetter, with an increased flood risk, and dry areas will get drier, with an increased risk of drought.

Water is an essential element for every life-sustaining activity on the planet, from hydration to agriculture to transportation and energy production. A robust audit of water usage best practices and sustainability efforts is thus a worthy goal for every facet of our society.

So where does golf fit into the complicated water equation? It’s a topic the USGA’s Green Section has been actively researching for the last 100-plus years — an endeavor that has only ramped up in urgency over the last several decades, especially in the Southwest, where warnings about a looming water shortage have been on a noticeably steady uptick.

“If we could have a scale to measure how dire it is from 1 to 10, I think we’d be on an 11 or 12,” said Matteo Serena, Ph.D., the USGA’s senior manager of irrigation research & services.

The problem, he notes, is not necessarily the water level in reservoirs, which can vary year to year based on rainfall or the melting of snowpack. Instead, Serena’s concern is the state of aquifers, which refers to underground saturated rock or soil that stores and transmits groundwater to sources like wells and springs. Aquifers are a principal source of groundwater in the Southwest — and Serena says they are at risk.

“Aquifers are getting depleted,” he said. “And we can’t really accurately measure aquifer recharge, or how much water is left.”

Unlike reservoirs, which can empty and refill, aquifers act like sponges rather than buckets. Squeeze a sponge, and it becomes depleted. When aquifers become depleted, they are rendered essentially unusable, because to refill them would take potentially thousands of years. And while reservoirs in states like California have been replenished by record rainfall in recent years, Serena said the pressure is still on.

“This is just temporary,” he said. “Historically speaking, we’re not in a much better situation than we were a few years ago.”

If we could have a scale to measure how dire it is from 1 to 10, I think we’d be on an 11 or 12.” Matteo Serena, Ph.D., USGA senior manager of irrigation research & services

For government agencies and authorities looking to set limits on water usage, golf courses make easy targets with their broad swaths of shining green grass. Cole Thompson, Ph.D., the USGA’s director of Green Section research, is keen to reshape the narrative that courses are water-wasting villains.

“Golf courses are very, very visible, so it’s easy to assume that they’re ubiquitous,” Thompson said. “While there are nearly 16,000 golf facilities in the U.S., they take up less than 1 percent of the arable land in the United States. We’re not going to solve the water crisis in the Southwestern United States by getting rid of golf courses. They are a very small land use category that delivers a lot in terms of life enrichment and economic value.”

Such perspective is important, Thompson said, because courses have so much more to offer than pure recreation.

“Even in a desert, a golf course can be a good use of resources because you’re going to get various benefits, including plant and animal habitat from the use of those resources, and other benefits like sequestering carbon dioxide,” he said. “All the plants on golf courses contribute to drawdown [storage of atmospheric carbon dioxide in plants and soil], mitigate urban heat islands by transpiring water, and provide habitat continuity in an otherwise rapidly developing world.”

Extensive research supports courses’ many contributions to improving and enriching their communities, for all the reasons Thompson stated above. Courses contribute to urban cooling, provide havens and habitats for wildlife with turfgrass and other vegetation that helps purify the air, and can even decrease stormwater runoff, not only helping to reduce the risk of flooding but also filtering and improving the quality of water that passes through the course.

Still, if current climate trends continue, courses could face an existential threat. Rising water costs and limited or restricted water usage could make operating a golf course unsustainable. It’s in everyone’s best interest to identify solutions that reconcile the appropriate maintenance of playing surfaces with the public perception of golf as a waste of precious resources. The fact is that courses in some areas of the country will need to adapt or face their potential demise. Fortunately, there are still plenty of reasons to be optimistic about golf’s future.

While sustainability conversations may seem to some to be a relatively recent phenomenon, pushed to the forefront of public consciousness by a spate of extreme weather, water usage and course-maintenance best practices are topics the USGA has prioritized since the Green Section’s founding in 1920. The goals of that era — improving golf course playing conditions and sustainability through research, education, course consulting, technology and championship agronomy — remain the same. USGA-led initiatives such as developing drought-tolerant grasses, decreasing irrigated acreage and leveraging sensor technology, are estimated to save U.S. courses more than $1.9 billion annually.

What does the game’s future look like in a potentially water-restricted world? Two Southwestern courses offer valuable case studies that shine a spotlight on the benefits of utilizing USGA-supported technology and innovations.

Mirabel Golf Club is a stunning Tom Fazio design set in the desert foothills of North Scottsdale, Ariz. The private club, opened in 2001, has a long-held reputation for immaculate conditions. Jeff Goren, the superintendent since course construction began in 2000, says that while Arizona has long been at the forefront of sustainability efforts, there has been pressure to improve even more in the last few years. Goren and his team have risen to the challenge, implementing several strategies that have made a significant difference in Mirabel’s water usage.

“We want firm surfaces, we want playability. That’s always been a desire,” Goren said. “We’re being pushed to the limits. To accomplish more reduction, we’re relying on more technology, moisture sensors and a more technical understanding of our moisture levels — what’s acceptable and tolerable.”

According to Goren, approximately 70 percent of Mirabel’s annual water usage occurs during Arizona’s hot summer months, roughly May through September. It’s a time during which Goren believes he can see the greatest amount of savings by experimenting with deficit irrigation, a strategy that involves replacing less water through irrigation than plants are likely to consume, to achieve desired growth, quality and playability. Goren is also actively testing plots of drought-resistant grasses on the practice area, with hopes of installing the best-performing breed on one of Mirabel’s holes by next summer. He also has a longstanding commitment to limiting the course’s overseeding practices.

“We made the decision years ago to not overseed our rough,” Goren said. “We do overseed the rough around the green complexes, but not the areas around the fairways. It’s a great visual, a classic Southwest desert look, and there’s water efficiencies there as well.”

Other strategies that have paid dividends for Goren are utilizing effluent water (recycled wastewater) for irrigation and topdressing the fairways with sand, a strategy he implemented in 2005.

“Native soil conditions are not ideal,” Goren said. “There’s a high clay content; infiltration rates were very poor. Combine that with effluent water being high in salts that increase the soil’s hold on water, and that resulted in water which was not available to the plant.”

By topdressing consistently over the years, Goren and his team have been able to build an improved foundation for optimal absorption.

“I call it a matrix,” Goren said, “a matrix of sand and organic matter that has built up over the years, and it provides a great growing medium. The improved soil creates healthier turf, deeper roots, more plant-available water, and we don’t have to irrigate as much. Capillary action of water has improved, there’s more air exchange, a better root structure – just a better environment for turf.”

Mirabel’s membership has also taken a proactive approach to sustainability, creating a water management task force that meets quarterly to discuss progress and potential future issues. For Goren, there is comfort in being prepared.

“We realize it’s not one thing that’s going to save 5, 10 or 20 percent of our water,” he said. “It’s going to be a multitude of things where I think you’re going to be able to make the difference.”

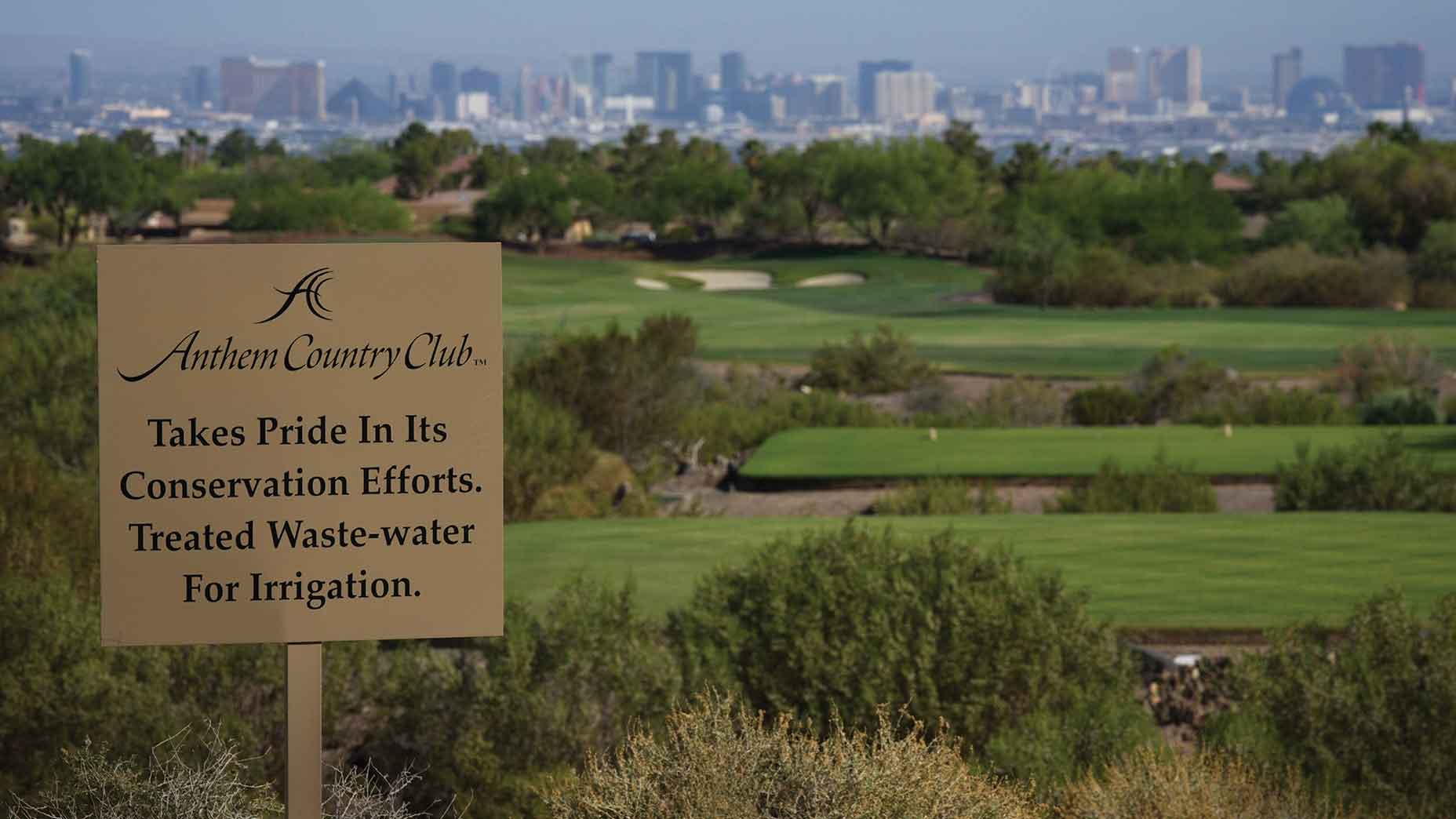

Three hundred miles northwest of Mirabel, Anthem Country Club in Henderson, Nev., has been preparing to comply with a newly introduced water-reduction mandate from the Southern Nevada Water Authority.

“It was scary when we heard it,” said Anthem director of agronomy James Symons, who was tasked with reducing Anthem’s water usage by 25 percent or be subject to costly fines.

Fortunately, Symons and his team had previously identified some important potential infrastructure improvements that could help the cause. Anthem, which opened in 1999, was in desperate need of a new irrigation system.

“Especially in the desert where you water virtually every single night, it seems there’s no supplemental rainfall to really give your pumps a break,” Symons said. “So everything just fails.”

The course’s irrigation system was completely redone in 2020, and new lining was also installed to stop leaks in the course’s irrigation lake. The next step was new greens, and when the news of the reduction mandate came through, Symons saw an opportunity.

“We were already lined up to do our green renovation in 2022,” Symons said. “I took it to my GM, Shelley Caiazzo, and eventually in an emergency presentation to our board, saying, Hey, there’s no way we’re becoming compliant with our current grass types, which are predominantly perennial ryegrass. I basically pitched to her that because we’re fortunate to be closing to do our greens renovation, we should take this opportunity to convert our fairways to bermudagrass.”

Symons got the needed sign-off and sourced Bandera bermuda sod — a drought-tolerant hybrid grass favored for its rapid establishment and fast recovery — for the course’s 35 acres of fairways, and 49 acres in total (including the practice facility and select areas of rough). In addition to replacing the grass, Symons and his team were actively engaged in a turf-removal project, converting more than 15 acres of out-of-play areas into desertscape or landscaping.

The results were almost immediate. Last year, Anthem was in full compliance with the reduction mandate ahead of schedule and is on track to meet the club’s goal this year as well.

Thanks to Symons’ efforts, last year Anthem received the City of Henderson’s inaugural Water Conservation Award, which celebrated the club’s endeavors to save more than 59 million gallons of water. Member reaction has been very positive.

“They realize it’s bigger than all of us,” Symons said of the course changes. “The playability has been fantastic. The roughs are great. There’s increased roll in the winter because the grass isn’t growing, and then in the summers it just looks beautiful. And at the end of the day, the course is going to be viable in the future.”

Regardless of what climate change has in store in terms of weather patterns, the USGA is committed to helping courses prepare. One such initiative, dubbed “15-30-45,” was introduced last year: a 15-year, $30 million commitment to help courses find solutions to reduce their water usage by as much as 45 percent. There is no mandate here; the USGA is simply trying to foster awareness on helpful topics like irrigation optimization, water sourcing and storage.

“We know the technologies already exist to make that happen,” said Matt Pringle, Ph.D., the managing director of the USGA Green Section. “And we at the USGA can invest in helping golf courses have the tools they need to make that happen.”

In addition to publishing recommendations and research for courses to utilize, the USGA understands that for courses to adopt a new practice, there needs to be confidence that the changes will benefit the course in both the short and long term. That’s why, in addition to supplying the information, the USGA is also partnering with select courses around the country to use them as test cases to demonstrate to other facilities where and when the water conservation potential of a strategy outweighs the investment and disruption required for implementation.

The USGA is a longtime supporter of research and development of drought-tolerant grasses, which use up to 20 percent less water than other varieties. But it’s one thing to read about the success of a given strategy, and another to see it in action. So, when a real-world example like Anthem Golf Club’s installation of Bandera bermudagrass validates a predicted outcome, it’s undeniably compelling for other facilities. According to the USGA, courses can expect to see a return on such investments in five to 10 years.

“We want to show what it would take to implement these strategies, because there’s a spectrum of cost and implementation challenges,” Thompson said. “What we want to show people is, if you want to save water, for whatever reason, we think you can. And based on what your motivations are and how much money you have to invest and what your goals are, let us show you what we think are your best options.”

Whenever changes are made to a course, a primary concern tends to be the course’s playability. With less water applied, will playing conditions become inferior? U.S. Open anchor site Pinehurst No. 2 recently hosted the world’s best golfers for the fourth time and provided yet another example of the success of sustainability practices.

“At Pinehurst No. 2, they dramatically reduced the number of acres of maintained turf, down to 56 acres,” Pringle said. “The overall course footprint is probably 200 to 300 acres. So, we’re talking about a quarter or less of the overall footprint being maintained turf. And the fact that we’re conducting Opens at No. 2, plus it’s a very high-end golf resort, tells me that you can play the game at all skill levels on 50 acres of turf.”

According to the Golf Course Superintendents Association of America’s most recent environmental profile, the median golf course maintains around 90 acres of turf.

What we want to show people is, if you want to save water, for whatever reason, we think you can. Cole Thompson, Ph.D., USGA director of Green Section research

“There’s an opportunity for turf reduction, even in areas of the country where they’ve been very proactive and ahead of the curve on water conservation,” Pringle said.

Courses can start on a sustainability and water-saving journey by asking a few simple questions: how much turf is being irrigated, and is that turf optimized to match a course’s environment? From there, the next step is deciding when and how that turf will be irrigated.

“These are things that you’ve got to have goals and resources to pull off,” Thompson said. “But they represent the big levers you can pull to really change the amount of water you use.”

Courses that want to dive deeper into conservation efforts can also investigate technological innovations like the moisture sensors utilized at Mirabel, and strategic irrigation systems that minimize water waste by delivering water to the roots instead of on the surface, where wind and evaporation can affect absorption. Also, the importance of basic maintenance practices cannot be overstated, per Thompson.

“We’ve got to make sure that the irrigation system is in good shape, that it’s not leaking, that it’s applying water where we want and at the rate that we want,” Thompson said. “That includes a lot of laborious but important maintenance in terms of making sure that the sprinkler heads are operating and functioning properly, that they’re level and the nozzles aren’t worn and you’re getting the precipitation rate you expect from them.”

Another resource currently in the works from the USGA Green Section is a Water Conservation Playbook. The playbook outlines conservation strategies that have proven efficacy from years of research, developed by university, industry and USGA experts, which are now being demonstrated by superintendents, architects and researchers to vet their real-world potential. A superintendent-facing version of the playbook will be published by the end of the year.

“The playbook is something we intend to share freely and broadly with the golf industry, both in this country and around the world,” Pringle said. “Most courses can’t pursue environmental stewardship as simply a feel-good project. It must make good business sense, and we’re always there with them on that. At the end of the day, anything we talk about has to be viable for them as a business. But that doesn’t mean that doing right as a business can’t also be doing right by the environment.”

Since its founding in 1894, the USGA’s mission has been to take a long view of the game. New initiatives are not based on immediate gains in the next quarter or fiscal year, but rather the next decade and generation. For the past 100 years, the USGA’s Green Section has endeavored to meet golf’s environmental challenges head-on. Thanks to its continuing efforts to advance the science of turfgrass management and conservation, there is reason for optimism. With mindful stewardship, the game we all love will not only endure, it will be positioned to thrive for the next 100 years, too.

Latest In News

Golf.com Editor

As a four-year member of Columbia’s inaugural class of female varsity golfers, Jessica can out-birdie everyone on the masthead. She can out-hustle them in the office, too, where she’s primarily responsible for producing both print and online features, and overseeing major special projects, such as GOLF’s inaugural Style Issue, which debuted in February 2018. Her original interview series, “A Round With,” debuted in November of 2015, and appeared in both in the magazine and in video form on GOLF.com.