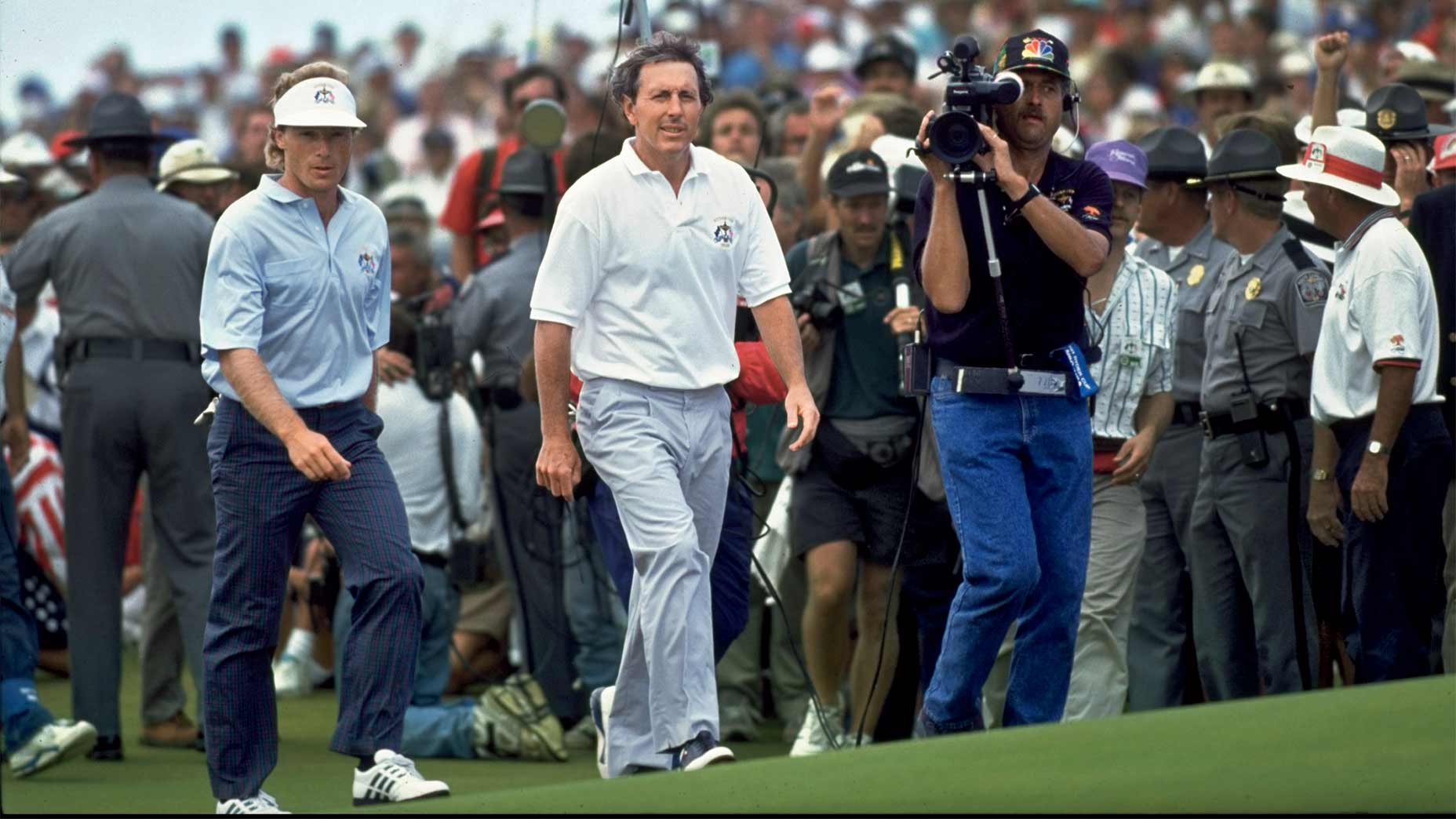

Thirty years ago this fall, I was standing by the 18th tee at the Ocean Course at Kiawah, soaking up the tensest atmosphere I’d ever felt in golf. It was the final match of the final day of the 1991 Ryder Cup, a taut, antagonistic competition that had lived up to its billing as The War by the Shore. Thinking back on it today, I can almost feel the air of excitement and unease. Everybody was on edge — the fans, the players, all of us on the NBC broadcast team. And no wonder. Everything was on the line.

Battling a brutally demanding course in blow-your-hat-off ocean-side conditions, Hale Irwin, for Team U.S.A., and Bernhard Langer, for the Europeans, had fought their way to all-square on the last. The U.S. held a one-point lead. This hole would decide the Cup.

Langer, with the honor, waggled his persimmon wood and found the fairway, which was framed by dunes. Next up, Irwin. The wind was whipping off the left, not ideal for Hale, whose go-to trajectory was a fade. The raucous crowd fell silent. Irwin swung. “That’s way left!” I said on-air, bad news beaming to American fans at home.

Or was it? In the chaos that ensued, with spectators swarming, it took me several minutes to march through the masses. My inclination was to head for the dunes — that’s the line Irwin’s drive appeared to be on. I figured I’d help look for the ball, a common practice for on-course reporters. Turned out I didn’t need to. As I pushed forward and the sea of humanity ahead of me parted, I could see it: Hale’s ball had somehow ended up not in the dunes, but in the fairway — a critical twist in a match to win it all.

How did the ball get there? All these years later, that question remains the greatest mystery of my broadcast career. It’s not as if I haven’t tried to find the answer. I’ve been getting ready to host an NBC/Golf Channel special, The Road to the Ryder Cup, which will air in advance of the 2021 Ryder Cup. As part of my preparation, I’ve scrutinized the footage. I’ve spoken to participants and first-hand witnesses, including a former PGA of America official who says that Irwin’s off-line drive struck her in the back. But I’ve yet to come across a satisfying explanation for what, exactly, transpired to allow that tee shot to settle in the fairway. Maybe the uncertainty is only fitting, given all the madness that went down that week.

At this point, enough has been written about the ’91 Ryder Cup to etch the stories into sporting lore: the fiery buildup to the competition, the bad blood between the teams, heating up as play progressed and boiling over into accusations of gamesmanship, even insinuations of cheating. Most agree that this was the Ryder Cup that changed it all, solidifying the event as the fiercest rivalry in golf.

It was a watershed in other ways as well. The first Ryder Cup on American soil broadcast on live network TV, it was also the first I’d ever covered. On Friday morning, before the opening shots of the opening matches, I already had an inkling of what I was in for. The mood was more than electric. The crowds were large and loud, the players and their captains all gathered by the first tee, a number of them pacing with spring-coiled anticipation. That was just the start.

By the time Sunday morning rolled around, more than one American player had gotten into it with Seve Ballesteros over coughing, change-jangling and other alleged shenanigans. Ballesteros, for his part, had described the American team as “11 nice guys … and Paul Azinger.”

Things had gotten real, to put it mildly. You didn’t have to be Nostradamus to foresee the matches going down to the wire. With that in mind, I picked up Irwin and Langer late in their front nine. Two things became clear: This match would decide the Cup, and par would be a good score on any hole coming in. On the par-5 16th, both made wizardly up-and-downs for par, leaving Irwin 1 up as they moved to the par-3 17th. Always fearsome, that hole was playing especially tough that day, long and into a strong wind quartering from the left. Langer, with a long iron, tugged his tee shot, but the ball hit a spectator (we could see that in the replay) and wound up in a hollow just left of the green. Irwin, playing a fairway wood, also started his tee shot left, trying to bring it back with his patented fade. That’s how I called it on the air, anyway. The TV cameras told a different story. Seconds later, they showed a ball landing on the right side of the green, coming to a stop some 15 feet behind the pin. Roars erupted.

“What a golf shot!” Johnny Miller said from the tower, as we cut to commercial. Except that it wasn’t. When we returned from break, our cameras picked up Irwin playing his second from the left side of the green, close to where Langer’s shot landed. The ball on the green wasn’t Irwin’s. Some joker in the crowd had tossed it there, but we never mentioned it on TV. I can only imagine how confusing that must have been for viewers at home.

Believe me, they weren’t alone. The scene on the course was bedlam, the crowds so thick and noisy and poorly controlled that it was hard to move around or hear my colleagues through my earpiece. Exciting? Sure. But unsettling too.

Meanwhile, on 17, Langer made par to Irwin’s bogey to square the match. A wild turn of events, with an even wilder one to come.

As Irwin recalls it, he didn’t think his tee shot on 18 was badly off-line. He says he figured it was destined for the light rough. He might be right. But that’s not what I said about it on the NBC broadcast. On the BBC, Peter Alliss’ call as Irwin struck the ball underscored the uncertainty. “I fancy a 4 could win this,” he said. “[But] oh, not now, if that’s gone where I think it’s gone.”

Remember: This was 30 years ago. We didn’t have Top Tracer. TV cameras were nowhere near as sophisticated as they are today. But here’s what I see when I watch the replay today: Footage shows the ball dive-bombing deep into the gallery and vanishing. It doesn’t carom out. At least not right away. There’s rustling in the crowd, and more rustling, moving closer to the fairway, as if the ball is still in motion on the ground. Whether the ball is moving on its own or being kicked along is impossible to say. Once again, we cut to commercial, and when we return there’s Irwin in the fairway, preparing for his second shot.

“If it wasn’t for the gallery, it probably would have rolled into the dunes, isn’t that correct?” Miller asked me on-air.

“I think so, Johnny,” I said. “I never saw it come out. And all of a sudden when we got out here, it was in pretty good shape.” And that was it. End of discussion.

In the aftermath of the event, the press didn’t say much about it either. At least not that I noticed. Only years later did I come across a quote from Langer, expressing puzzlement over Irwin’s drive, which he described as snap-hooked “40 yards left of where his ball ended up.” As this article goes live, I’ve not had a chance to speak with Bernhard directly about this. But close friends of his have said that Langer has always had a hard time wrapping his head around what happened.

Yet another perspective comes from Kathy Jorden, who was then a young official with the PGA of America. Jorden told me that as she recalled it, she was standing to the left of the 18th fairway with her boss, just inside the ropes. They were making their way toward the green to prepare for the trophy presentation.

Hearing a cry of “Fore,” Jorden says that she turned and ducked. An instant later, Irwin’s drive smacked her in the small of the back. She says that she had a welt to prove it. What she can’t confirm is what happened next. She never saw the ball bounce in the fairway. But here’s the thing: Watching the footage today, there is no definitive rope line holding back the crowd. It’s likely Jorden was surrounded by a mass of people. I say this not to impugn anyone. I just believe it speaks to the chaos of the moment and the way memory can blur over time.

Still others on hand that day give different accounts. Asked recently about Irwin’s drive, Bernard Gallacher, the European captain in 1991, said that in the immediate aftermath of the competition, he and his players felt that Hale must have gotten “a fortunate bounce off a spectator.” But, he added, “I was told a few days later by a European supporter that he witnessed Hale’s ball being thrown back into play. I considered it water under the bridge.”

The rest is history as well. Irwin went on to make bogey on 18, and when Langer missed a six-footer for par, their match was halved, giving the U.S. the half-point it needed to win the Cup. Would a different outcome of Irwin’s drive led to a different result in the team competition? We’ll never know, just as we’ll never know what happened to Irwin’s tee shot. I’m convinced of that. But I’m also sure we’ll never see an incident quite like it again — not with the TV coverage we have today (to say nothing of fans filming with their phones).

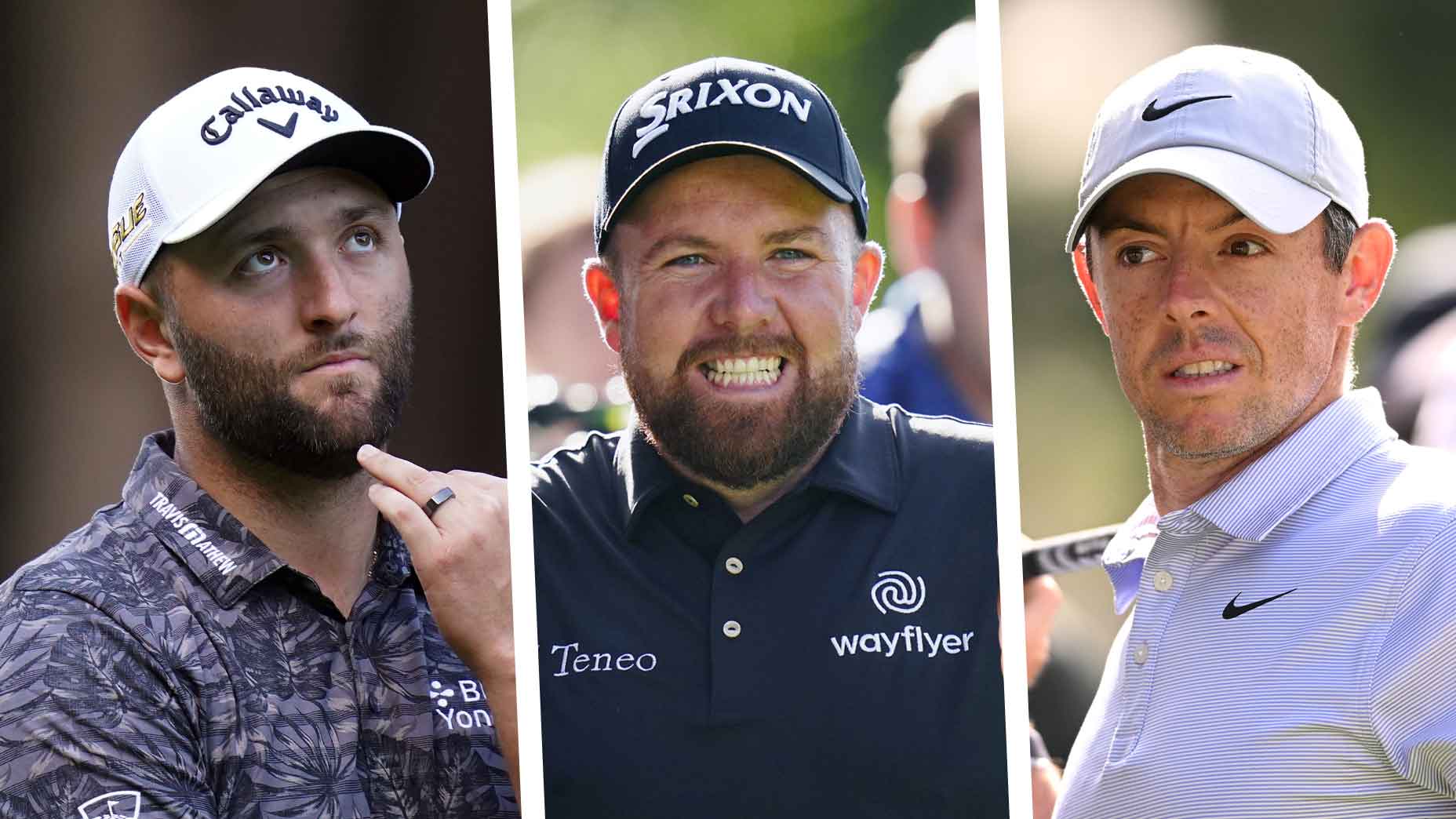

That’s partly due to the mayhem at Kiawah. It helped transform the Ryder Cup into the most closely scrutinized event in golf — and the most compelling. Now comes Whistling Straits. If it’s even half as riveting as ’91, hold onto your seats.

Additional reporting for this story by Josh Sens.