Before J.J. Spaun’s 64-footer? Mini tours, money games and a coach’s belief

Before J.J. Spaun’s 64-footer? Mini tours, money games and a coach’s belief

Did this Texas pro really make 51 holes-in-one? We put his astounding claim to the test

One recent evening at a sleepy business complex in a suburb north of Houston, a retired golf pro with a large personality and a limp shuffled with a cane into a brightly lit office, sat down and submitted to a lie detector test.

It had been six years since Mancil Davis was physically able to play the game he loves, and even longer since he’d been cross-examined on his claim to fame.

But at 66, with a genial demeanor and a deep voice laced with a West Texas twang, he still answers to the moniker he earned in his prime.

For decades, he’s been known as the King of Aces, a nickname stemming from his astounding exploits: He has made 51 holes-in-one, which is widely accepted as an unrivaled mark for a professional golfer.

Fifty-one.

Let that sink in.

RELATED: Listen to our podcast about the King of Aces by clicking the banner below:

For the average weekend golfer, the odds of making a hole-in-one are roughly 1 in 12,500. Crunch the numbers — 12,500 x 12,500 x 12,500 and so on — and the odds of making multiple aces soar into the stratosphere. That’s true for everyone, even for a serious stick like Davis, who played a lot of golf and played it well.

Though there’s no way to nail down the precise probability of what he pulled off — you’d have to know exactly how many regulation tries he had in his lifetime — the likelihood is 1 in many, many, billions, somewhere in the neighborhood of winning the Powerball every few years.

Hole-in-one accounts, of course, are often eyebrow-raisers. No one believes the most outlandish of them: that Kim Jong Il, North Korea’s late Dear Leader, once made five in a single round. But even factual reports can have the whiff of fiction. The longest ace ever registered on a par-4 — 447 yards! — took place on a course called — ahem — Miracle Hill.

The vagaries of record-keeping help explain why the Guinness Book of World Records is cautious when it comes to touting aces. The organization limits its recognition of most hole-in-one records to professional events (Hal Sutton and Robert Allenby are tied on the PGA Tour, with 10), the ones that are easiest to verify.

Attesting to the rest is often he-said, she-said. An amateur named Norman Manley, for instance, is said to have notched 59 aces. But whatever witnesses he had are largely scattered to the wind, and Manley himself, who would be in his late-90s today, has proven difficult to locate. (GOLF.com’s attempts to reach him were unsuccessful.)

Mancil Davis is different. He’s the leader in the clubhouse among golf professionals, and he’s still around to detail his feats.

He made his first hole-in-one in 1966 and his last in 2007.

It’s unlikely, though, that he’ll make another.

His balance is too poor now for him to swing a club, the result of a mishap in 2014 that was every bit as fluky as the time he hooked a long-iron off a tree into the cup, or that other ace he clanked off a sprinkler head.

Some holes-in-one are like that. They strain credulity.

Davis has faced doubters.

But he’s never minded.

When GOLF.com requested that he take a polygraph, he was happy to comply.

“Doesn’t bother me a bit,” he says. “I know that it’s all true because I was there.”

*****

“Do people refer to you as Mancil?”

A curveball to start the interrogation, standard polygraph procedure to set a baseline for truth and deception.

Davis hesitates.

Truth is, his parents named him Ronald Mancil Davis. But Mancil was how everybody knew him when he was growing up in Odessa, Texas, a polite-talking, yes-sir, no-ma’am country kid with a quick smile and a silken swing. Odessa in those days was a dusty oil-boom town, a place of tumbleweeds and open spaces and fortunes made in black gold overnight.

Mancil would hit pay dirt of a different kind.

Introduced to golf when he was six by his Buick dealer father, he was shooting in the 70s by middle school, a top player on the west Texas junior circuit. He first ace came in the heat of competition, on the 165-yard, par-3 3rd hole at a local track called Golden Acres Country Club.

Tight draw with a 3-iron. Hop. Skip. Jar!

There were high-fives and huzzahs, but since he wasn’t buying drinks, that was about it for the celebrations.

“It was fun,” Davis says. “But really, my main thought was, ‘Cool, I get to hit first on the next tee.’”

He got to do that often. Soon, the aces began to come in bunches. Three in a week. Five in a month. Eight in a year-long span that ended in mid-1967.

It was a staggering run. But Davis, being a kid, soaked it up with youthful matter-of-factness.

“To me, it just meant that I was making a good score,” Davis says. “Which meant I had a better chance of winning a little silver trophy to put on my shelf.”

Adults noticed, though. At Odessa Country Club, where Davis’s family belonged, their reactions to him ranged from sweet to cynical.

“It was either, ‘Hey, there Ace, you headed out to get another?’ Davis says. “Or, ‘Hey, there, kid, I heard about your aces,’ and then under their breath, ‘Yeah, sure. right.’”

Either way, it was a story. The local paper caught wind, and the resulting article got picked up by the wires and dispatched around the world. Fifteen minutes of primetime limelight followed. CBS summoned young Mancil to New York to appear as a contestant on “I’ve Got a Secret,” a popular weeknight game show hosted by Steve Allen.

A black-and-white clip, alive and well on YouTube, shows a 12-year-old boy, with a drawl as thick as crude oil, fielding questions from a panel of celebrity guests.

“Is it something sporting?”

“Yes, sir?”

“It has nothing to do with cattle?”

“No ma’am.”

“Do you move from one place to another as you do it.”

“Yes ma’am.”

No one can guess what his secret is.

*****

Back in Odessa, time breezed by and the tally mounted. More holes-in-one in high school, and then again in college, where Davis played golf on a scholarship at LSU. At that level of the game, he was good, not great, “the eighth man,” Davis says, “on a team of five.” But the golf gods mete out favors in mysterious ways. By his 20th birthday, Davis had shot his age in aces, the only golfer ever known to have one for every candle on his cake.

“It probably sounds strange,” he says. “But it got to the point where I was expecting to make one almost anytime I played.”

In every instance, eyewitnesses could vouch. One was Terry Alsup, also from Odessa, who watched Davis make two: the first when Alsup was a high school senior and Davis was 11, the second nearly 15 years later, when they worked at the same course as assistant club pros. As Alsup, now 73, recalls, both shots benefited from friendly bounces, one off a tarp, the other a skidder with a fairway wood that shook the stick and dropped.

After the latter, Alsup asked Davis to come with him to Vegas, because “man, you must have a gold brick up your ass.”

Davis waved him off.

“Doesn’t work like that,” he said. “When I play craps, all I roll are 1’s.”

What Davis dreamed of playing was the PGA Tour, which he did, for an eye-blink, in the 1970s, Monday qualifying into three events. For a year, he scratched it out on the Canadian Tour, barely breaking even. He had grit and gumption. But grinding couldn’t make up for the gaps in his game, the biggest being his failure to find many fairways. An emblematic moment came during the Monday qualifier for the 1978 Bryon Nelson Classic, when Davis hooked a tee ball out-of-bounds and off the course, across two lanes of an adjacent freeway. He missed qualifying by a single shot.

“That was always my problem,” Davis says. “I hit my irons like Doug Sanders, and my driver like Colonel Sanders.”

Sanders — Doug, not Colonel — was Davis’s first boss in the club business, at Woodlands Inn and Country Club, outside Houston, where the flamboyant former Tour star was director of golf. Davis came aboard as an assistant an pro. Though he still fantasized about a life on Tour, this was a life within his reach, and a nice life at that. It allowed for lots of golf while thrusting Davis into Sanders’ magnetic orbit.

ADVERTISEMENT

Davis met golf legends — Trevino, Weiskopf, Nicklaus, Palmer — and befriended luminaries such as Willie Nelson and Evel Knievel. Both became golf buddies, thought they cut contrasting figures on the course. Where Nelson played shirtless, in friendly games, with a cloud of marijuana smoke wafting in his wake, Knievel was a hustler, drawn to high stakes matches against guys with names like Little Dog, Slim and Red. When they played at the Woodlands, Knievel and his cohort brought their own bagmen. Not caddies. Actual bagmen, hauling suitcases filled with cash so that wagers could be settled after every hole.

In the many rounds he played with both the singer and the stuntman, Davis recognized that they had one trait in common.

“I never saw either of them make an ace,” he says.

Davis himself continued making plenty, including one during a playing lesson on the 3rd hole at the Woodlands. Let the record show that the 3rd is a par-4, and that Davis, in his lifetime, has 10 double-eagles, another category in which he tops the field.

*****

How?

How did he do it?

Not everyone believed that Davis actually did.

Writing in the early ‘80s in the Dallas Morning News, the future ESPN talking head Skip Bayless summed up the skepticism with a question.

“It seems fair to ask: Is the King of Aces dealing with a full deck?”

Davis was unruffled by the disbelief.

“My feeling always was, ‘Hey, at least they’re talking about me,’” he says.

Plus, he had an answer.

His secret, he liked to say, was that he aimed at the hole. In that way, he was unlike Ben Hogan, who recorded just four aces in the course of his career, a figure Hogan explained in classic Hogan fashion: He rarely deemed it sensible to fire straight at the flag.

There was something else to Davis, though. Something in his psyche.

“Jack Nicklaus used to say, ‘Go to the movies in your mind,’” Davis says. “Well, when you put me on a tee box of a par-3 with an iron in my hand, it was like I was watching things in IMAX, giant screen. I could see it all in living color.”

But seeing isn’t doing, and if he’d had a clue for how to pass along his gifts, he might have made a killing teaching the mental game.

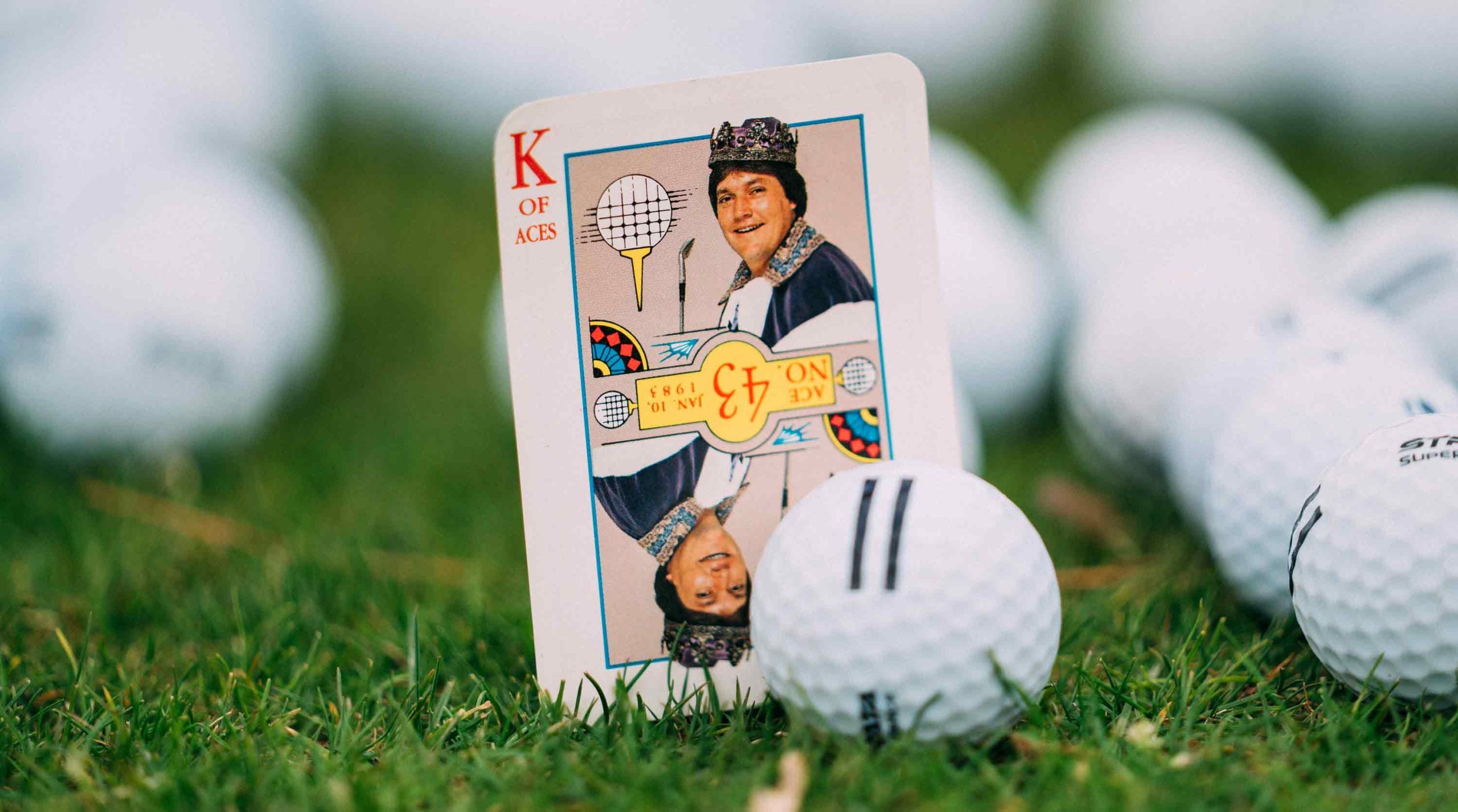

Where he wound up making some dough was as the King of Aces, a character dreamed up for him by John Everhart, a Dallas insurance salesman with a creative streak. In 1981, when the two men first crossed paths, Everhart was exploring a niche sector that would soon become an industry staple: He sold hole-in-one-insurance, coverage for prize giveaways at golf events. At the time, this was a novelty. The only other player in the space was Lloyd’s of London, but its policies were scarce and steeply priced. Everhart was smart enough to see he had a wedge: He could undersell Lloyd’s policies and still make a profit.

The sweet spot, he discovered, was the overlapping interests of auto dealerships and tournament organizers: By rolling out a Cadillac alongside a par-3, you could advertise the car while generating buzz for the event.

A good business, no doubt, and Everhart wanted a face to help promote it, someone with golf street-cred. He reached out to Art Wall, the former Masters champ and then record-holder for holes-in-one by a pro, with 41. But Wall was too expensive, a non-starter.

A few weeks passed. Everhart was on the verge of giving up his search when he stumbled across an article in the Dallas Morning News.

“It seemed like almost a miracle,” Everhart, now 83, recalls. “Turned out there was a club pro who had just scored a hole-in-one, his 33rd.”

Everhart contacted Davis, and they sealed a deal.

In exchange for a percentage of each policy sold, Davis would adopt an alter-ego, the King of Aces, a roving PR man and entertainer, a fixture at trade shows and corporate outings. One of his roles was to stand at a par-3 at charity events, smacking shots with each group that passed through. If Davis made an ace, it would count toward the group’s score, but not toward Davis’s career hole-in-one tally unless he jarred a shot on his first swing of the day.

That happened twice. In both cases, Davis waited for the last groups to go by then finished out the round to make his ace official.

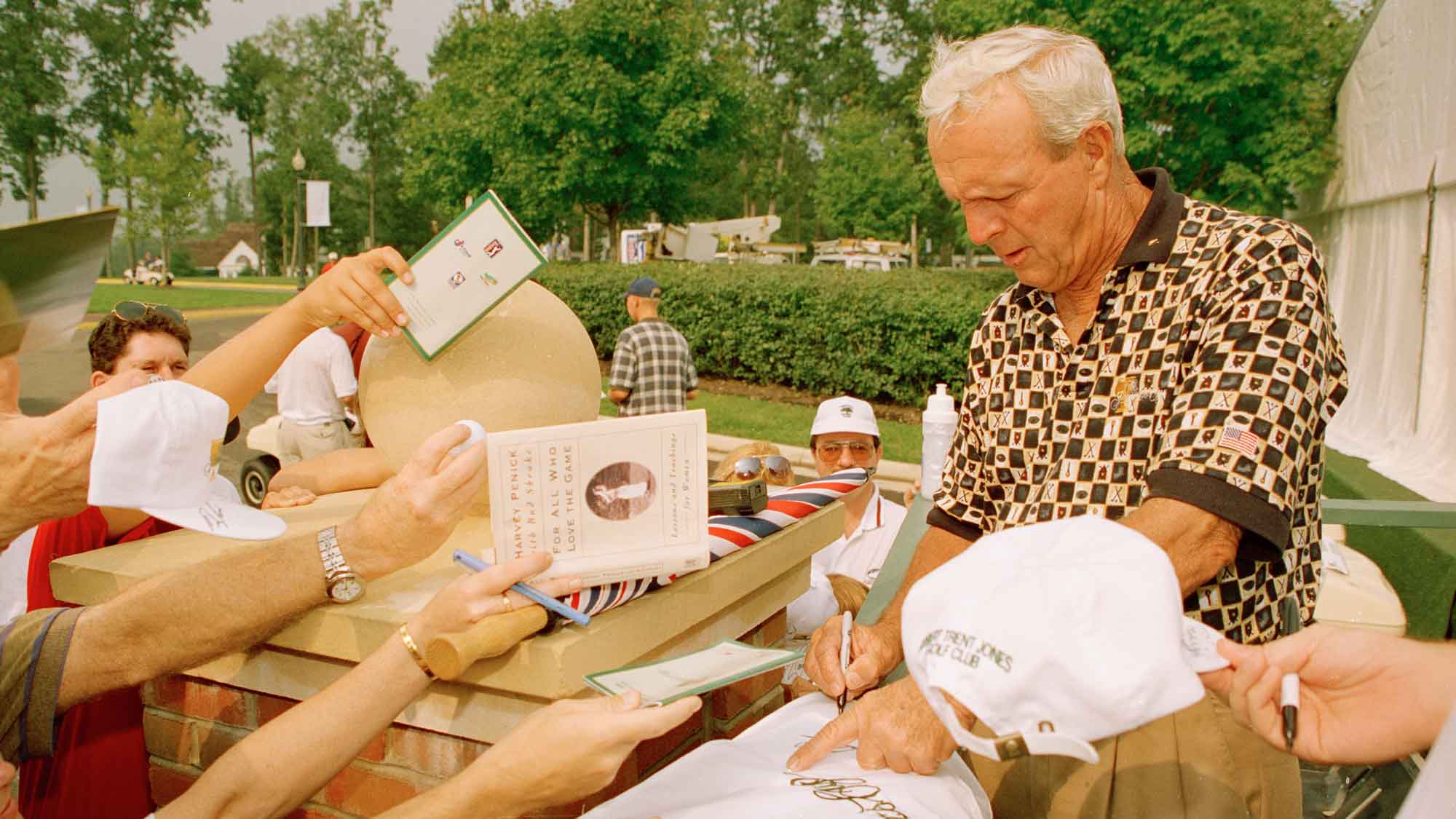

There were downsides to the gig, Davis says, like the regal costume he was sometimes asked to wear, a getup he found goofy, with a purple robe and crown. But mostly he enjoyed it.

“It basically involved playing golf, partying and talking to people,” he says. “And it turned out I was pretty good at all three.

In 1986, Davis and Everhart parted ways after a contract disagreement. But their union had been fruitful. It helped birth an industry, and supplied Davis with grist for the storytelling mill.

*****

“In your whole life have you ever made even one mistake?”

Another question for the polygraph, and it’s loaded.

First of all, who hasn’t?

The problem for most people would be picking out just one.

The slip up that sticks with Davis came in 2014. The USGA Junior Amateur Championship was on its way to Carlton Woods, just north of Houston, where Davis, following stints at courses from coast to coast, was working as an assistant pro. One morning, in the throes of tournament setup, he showed up early to help out. In the pre-dawn dimness, he saw a woman struggling with some cargo.

“I’m from West Texas,” he says. “I was raised that when you see someone who needs assistance, you don’t just stand there.”

Rushing to lend a hand, Davis mis-stepped off a loading dock, a four-foot drop. His right foot landed at an awkward angle. He knew that it was bad, just not how bad. Due to medical delays and bureaucratic snags in his workman’s compensation, it took several weeks to find out that he’d ruptured his Achilles tendon. To repair it properly, re-attachment surgery should have happened sooner than it did.

“The irony is that if I’d slipped and fallen at a McDonald’s, I’d be a millionaire by now,” Davis says. “But no such luck.”

Not long after, a blood clot formed around his injury. It migrated up his body and caused a stroke. Though the stroke left his speech and sense of humor intact, it destroyed his balance and diminished his eyesight. Even if he could still hit a golf ball, he wouldn’t be able to track its flight.

Stripped of his capacity to play the game, Davis battled depression, but he says gotten past that. He has plenty to live for, happily married with three grown daughters and wellspring of memories to drawn on. Time has brought perspective. Good breaks, bad breaks. Everybody gets them.

“Fact is, most of the bounces in life have gone my way,” he says.

Still, there’s a lot he misses. The smell of grass on a fresh mown course. The glint of morning sunlight on a dewy fairway. The sense of possibility in every round that’s no less real for being so distant.

“It’s something every golfer can relate to,” Davis says. “Maybe they can’t think of winning the U.S. Open or the Masters or the LPGA. But they know there’s that one perfect autumn day when the wind is just right and the light is shining just so and they catch that 5-iron square and they’ve just hit a shot that Tiger Woods couldn’t do any better.”

*****

“Are you telling the truth when you say you have made 51 official holes-in-one in your golf career?”

Final question. The one that really matters.

Partly because of his age, and partly his condition, Davis has occasional memory glitches, though mostly they are things like, Where’d I leave my keys?

But get him going on his aces, and his recollections roll, uninterrupted. That first streak in Odessa, way back when. The clusters that came in high school in college. The bushels bagged at various courses — in Dallas, Tahoe, St. Simons Island — where he worked the pro shop and played routinely after-hours. Some stand out more than others. A 2-iron on vacation in Acapulco. A 6-iron, at the Woodlands, when he said aloud, mid-waggle, “I’m going to knock this in,” then did.

After all these years, he’s hard-pressed to name them all in order. But does he really have to?

Are you telling the truth when you say you have made 51 official holes-in-one in your golf career?

The question lingers.

A sensor has been clipped to his index finger. A blood pressure gauge is wrapped around his arm. His biorhythms run through the wires to a computer, squiggles register on the screen. The polygraph administrator squints and reads them. Leaning back, she pauses.

“It looks to me,” she says, “like you totally aced this one.”

The machine believes Davis. Is it such a leap for us to believe him, too?

ADVERTISEMENT