It’s only fitting, at a tournament co-founded by Bobby Jones, that amateurs are always part of the subplot. But their narratives vary from year to year. This week, as the world’s best make their way once more down Magnolia Lane, we’re revisiting the unlikely story of a Masters amateur from decades ago. The article below, first published in the January 2004 issue of GOLF Magazine, traces the up-from-nothing rise — and tragic fall — of Jeff Thomas, a tough but troubled amateur from New Jersey who took his homemade swing to Augusta National in 1994, leaving a mark both on the course and off it. For unlimited access to the full GOLF Magazine digital archive, join InsideGOLF today; you’ll enjoy $140 of value for only $39.99/year.

***

In the suffocating heat of a Florida summer, in the bleak motel room where they would find his body, he stood hitting iron shots. The balls caromed off his tattered couch. They crashed against the wall, leaving shallow craters in the plaster, like pitch marks in a firm green. His back ached. His hands quaked from the alcohol. But the shots he struck with a 3-iron were clean, crisp whistles off the mangy carpet — the kind of shots that on the course still drew whispers of what might have been.

No one heard the pounding, or at least no one complained. At the Heritage Inn in Hobe Sound, guests have problems of their own. Motel assistant manager Mehroon Esmail hadn’t noticed the dents her tenant was making in room 234. But she had seen the photos he kept, photos of him posing with Tiger Woods at the U.S. Amateur, striding the fairways of Augusta National with Arnold Palmer.

He’d shown her the snapshots as he stood in his doorway in a rumpled T-shirt on the day he asked if the motel had any work for him. “I said, ‘But if you are so good at golf, you must be very rich,’” Esmail says. “He just smiled.”

Later, when his doorway was crisscrossed with yellow police tape, the photos lay in his room amid a scattering of golf balls. At age 44, he’d been scratching out a living as a caddie at McArthur Golf Club, a lavish private retreat where members sometimes dropped in via helicopter.

Around McArthur the caddie was known by name and reputation: Jeff Thomas, the record-setting New Jersey amateur who’d sparkled for a decade, then flickered out of view. But few McArthur golfers knew of the reckless choices that had led him from the top of the amateur ranks to the caddie shack.

And no one could know that the man who’d once slept in the Crow’s Nest at Augusta would spend his last nights in a washed-out Florida motel. “People hear how he died and where he died, and they think, ‘Oh, he was just another bum,’ ” says Paul Piccolo, one of Thomas’s friends. “Jeff Thomas was a lot of things, but he wasn’t just another bum.”

Sports give rise to two compelling but competing archetypes: the triumphant underdog and the star who loses everything. Jeff Thomas was both.

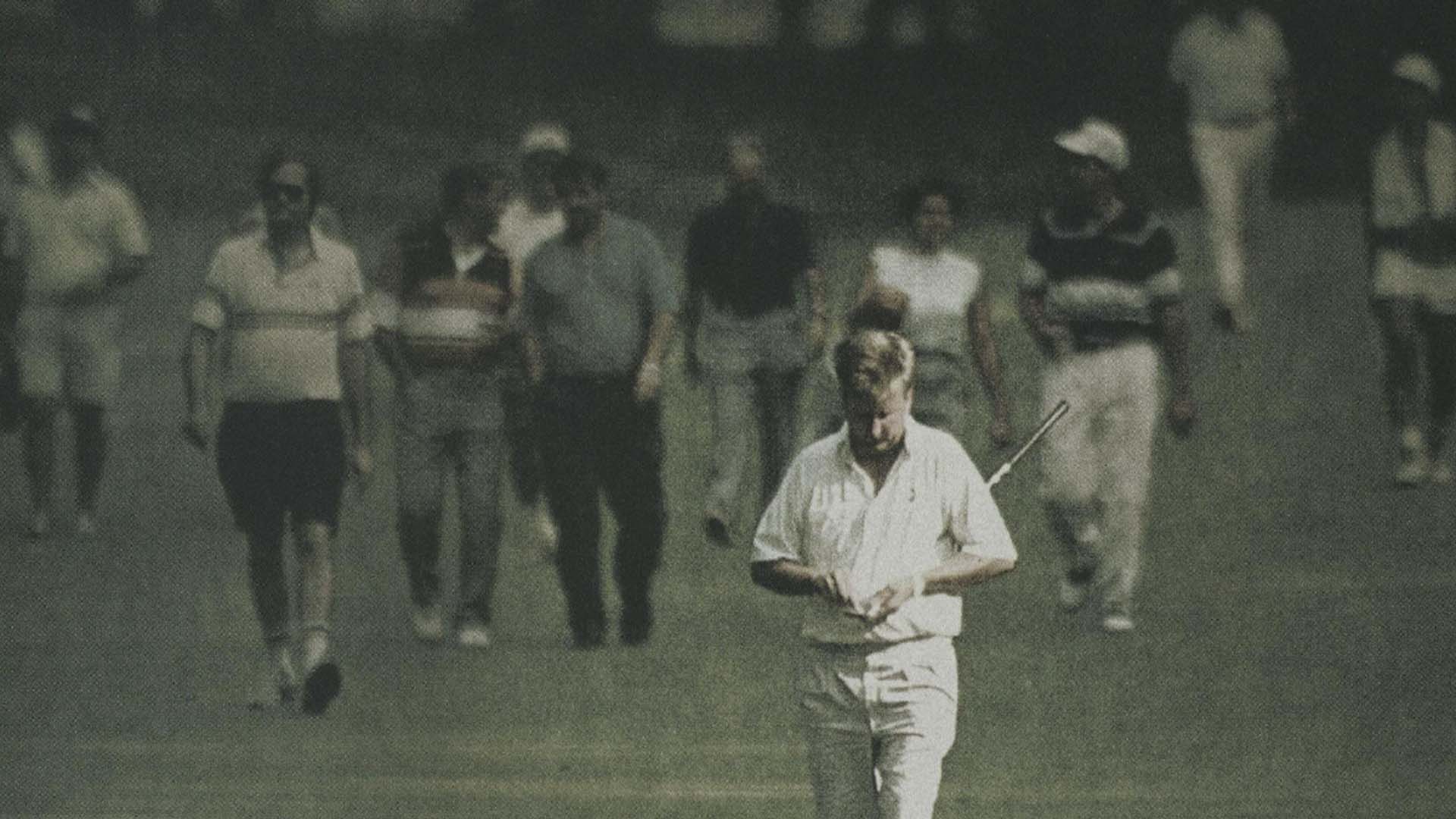

In South Plainfield, N.J., where he grew up, he emerged as an unlikely star, a blue-collar kid with a homemade swing who came to dominate a blue-blood sport.

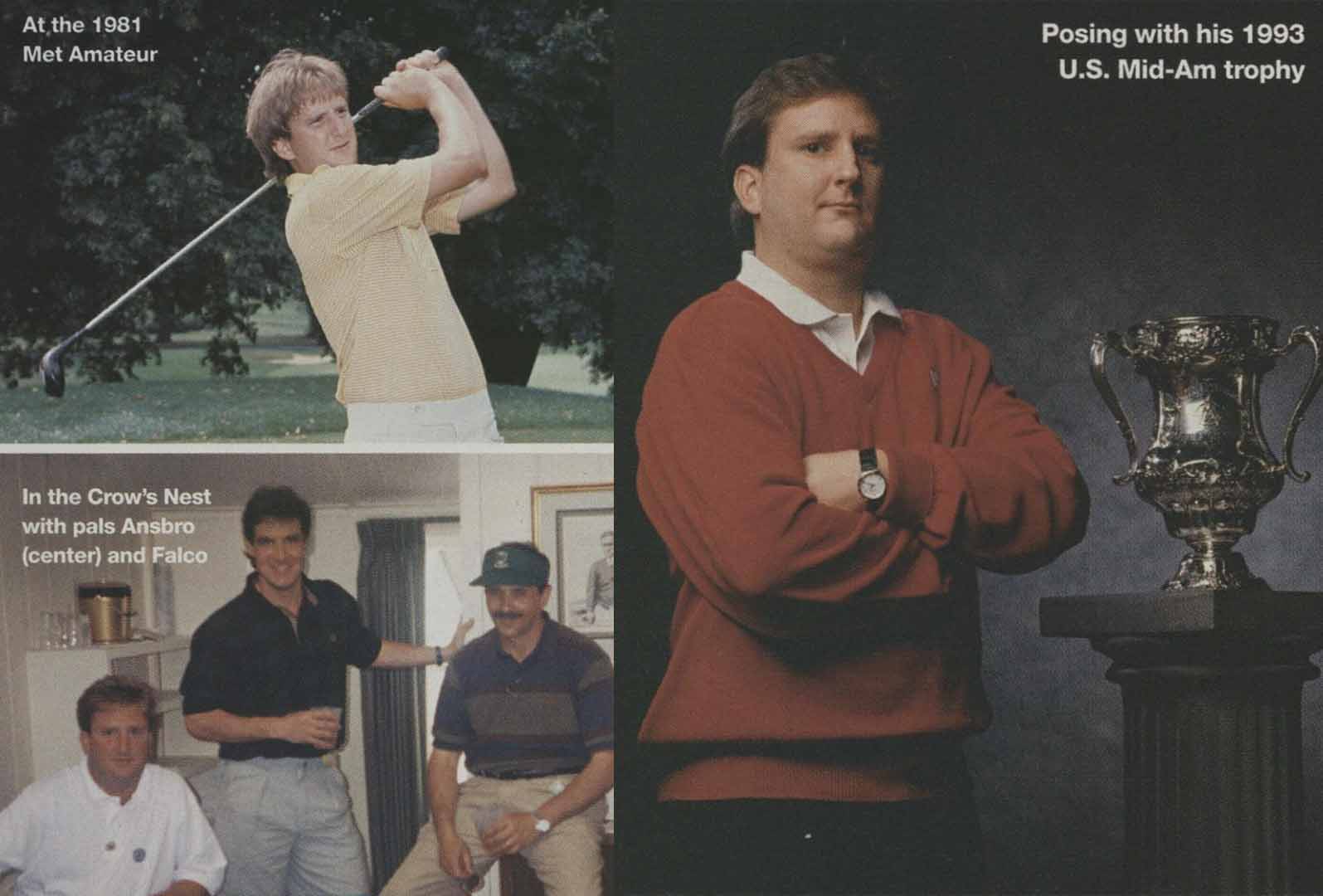

Between 1981 and 1996, Thomas won dozens of amateur titles. He ran up a record unmatched in New Jersey history and was widely considered the finest golfer the Garden State ever produced. He won the 1993 U.S. Mid-Amateur and the 1996 Sunnehanna Amateur. He won the New Jersey State Amateur more times — eight — than anyone else, once by a record 11 strokes.

But Thomas’s talent was matched by his knack for self-destruction. He didn’t just win; he won injured and he won hung over. He would stumble into tournaments minutes before his tee time, without a practice swing, fresh from an all-night bar binge. “A golfing savant” one friend called him, and what else would you call a man who played with such stunning precision when his life was spinning out of control?

“Jeff had demons, but golf was an environment where he could thrive,” says Tom Ansbro, a friend and former college teammate. “Once he stepped off the course, that’s when things would spiral down.”

Thomas picked up the game from his father, Charlie, a former high-school golfer who became a chemical engineer. Charlie built smelting furnaces for a mining company. He also taught his three sons to swing a club, but only lanky Jeff, the middle kid, had his dad’s deft hands and competitive drive. “I wasn’t a bad player, but there was no point trying to keep up with Jeff,” says older brother Alan, now a chemist in Arizona. “He would just laugh and blow me away.”

Thomas practiced every day until dusk at Plainfield West, a nine-holer that kept its greens Shinnecock-slick. In time, he honed a short game that made other players shake their heads in wonder, his touch and imagination more than compensating for an unorthodox swing. “He took it inside, he was handsy and he sort of trapped the ball,” says Ron Vannelli, who played against Thomas on the New Jersey amateur circuit. “The only thing right about his game was his score.”

By age 16, Thomas had won the junior and men’s club championships at Plainfield West. In those days he wore his dirty-blond hair down to his shoulders and played gloveless. He cut the figure of a rebel and lived up to the image. After winning a tournament in Massachusetts, Thomas was awarded gift certificates for lessons with famed instructor Bob Toski. He handed them back. “My father already taught me how to play,” he said.

Thomas wasn’t just bitten by the golf bug, he was gobbled up by it. He liked to recite whole paragraphs from the rule book. He memorized trivia and subjected playing partners to pop quizzes. “Quick,” he’d say in his nasal voice. “Who was the last amateur to win the U.S. Open and by how many strokes?”

After high school, while his brothers pursued college and careers, Thomas stayed home and became a full-time golf bum. He worked odd jobs, but never stuck with one that kept him from a tee time. He’d play with anyone, anywhere. His New Jersey ball-buster’s sense of humor translated well into on-course banter.

“Why don’t you try slowing down your backswing,” he’d tell a fellow golfer, “like so we can see it.” He did Bogart impressions. He reeled off lines from Caddyshack.

People liked playing golf with Jeff Thomas. They knew he had a bright future. Businessmen backed him in high-stakes matches; country-clubbers used him as a ringer in their Sunday-morning skins games.

“Jeff was hyperactive when he was young and golf allowed him to concentrate, so in that sense it was therapeutic,” says brother Alan. “But it became an obsession. He was addicted to the competition, always looking to bet you in a game.”

Thomas’s long days on the course were followed by long nights in bars, where he didn’t carry himself as well. Fueled by alcohol, his playful chatter turned belligerent and drew him into brawls. Gregarious and gracious when he wasn’t drinking, Thomas turned dark with a few beers in him. At the 1994 MGA/MetLife Public Links at Spook Rock Golf Course in New York, he shot a final nine 41 to lose the tournament by a stroke, then brooded in the clubhouse bar while the winner gave his acceptance speech.

“You didn’t win it!” Thomas blurted in the hushed barroom. “I f—ing gave it to you.”

“It was no secret that he had a problem, but Jeff kept people at arm’s length,” says Lee Richardson, who played alongside Thomas as an amateur. “When I suggested he get into a 12-step program, he said, ‘Sounds great. Why don’t we go out for a few drinks and you can tell me all about it.’ ”

Golf opened doors for Thomas, but he had a habit of slamming them shut. In 1979, two years out of high school and still unknown outside his home state, he was recruited by the golf coach at Ramapo College, where he made good on his reputation as a player and a renegade. He scuffled with teammates. He brought two kinds of bags to tournaments: one for his clubs, the other for marijuana.

One morning before a match, he told teammate Tom Ansbro that he’d “been to Boca” — his term for vomiting the morning after a late-night binge. (Thomas had briefly attended the College of Boca Raton in Florida.) “He was so hung over he was puking bile,” Ansbro says. “Then he goes out and shoots 68.”

Thomas earned All-American honors four times and led Ramapo to a Division III national title. But his off-course habits finally became too much. He was kicked off the team and dropped out of school.

Still, he succeeded on the course. Thomas won his first New Jersey State Amateur in 1981 and repeated the feat seven times in the next 13 years. He had a flair for the dramatic and the bizarre. At the 1990 state amateur at Hominy Hill Golf Course in Colts Neck, he closed birdie-birdie-birdie to take the title by a stroke. He won an early-round match at a Metropolitan Golf Association event after showing up and asking his opponent if he could borrow a pair of pants — hustling from another tournament to this one, Thomas had neglected to do a load of wash.

But if his preparation was sometimes lacking, his passion was not: At the annual Hochster Memorial one year, Thomas peeled the shoes from his badly blistered feet and limped through the final nine in his socks. Some of his exploits took on the whiff of urban legend. In 1996, after finishing second in his quest for a ninth state amateur, he sat in the clubhouse, downing Budweisers one after another. “It’s late and Jeff starts talking about playing in the Sunnehanna,” says Vannelli, referring to a prestigious Pennsylvania tournament whose champions include Ben Crenshaw, Billy Andrade and Scott Verplank. “I say, “When’s that?’ And he says, “tomorrow.’ So I laugh and go home. The next day, I find out that Jeff stayed up all night partying, then drove across the state to make his morning tee time.”

Thomas didn’t just play in the Sunnehanna. He won it in the finals over Steve Scott, who later that year would finish runner-up in the US. Amateur to Tiger Woods.

Clubhouse pals and playing partners urged him to turn pro. “I’d say, ‘Jeff, this amateur stuff is great, but you need a plan, ” says his old friend Joseph Falco Jr. “ ‘It’s time to start earning money — time to move to a bigger pond.’ ” But Thomas felt comfortable where he was. When a local businessman offered him $10,000 to make a run at the Tour, Thomas declined. He told a girlfriend that he idolized the old-time amateurs. “He’d take me to Golf House” — the USGA museum in Far Hills, N.J. — “and we’d look at all the old photos,” says Carolyn Vadala, who was engaged to Thomas when the two were in their early 20s. “He talked about how Bobby Jones had kept it pure and how he wanted to do the same.”

But his moony talk masked self-doubt. Once, in the Plainfield West clubhouse, head pro Eddie Famula asked Thomas why he wasn’t competing against the players on TV. “Are you kidding?” Thomas said. “I’m not as good as those guys.”

As the years passed, his romantic image of the amateur golfer bore less and less resemblance to his reality. He lived in South Plainfield with his mother (his father died of liver cancer in 1985), in a house so cluttered with golf trophies that he used one as a water dish for his dog. When he wasn’t on the course, he rented old movies and went clamming on the Jersey Shore with friends. He drifted out of touch with his brothers as his relationship with his mother, Joan, grew tighter.

“Jeff and her in that house alone, they kept each other together,” Alan Thomas says. “She was his secretary, his bank, his maid. Jeff needed her and she needed him.”

Thomas was never short of playing partners but often short of cash. He bought knickknacks at garage sales and tried to sell them at a profit. He landed work as a limousine driver and a water-softener salesman but lost those jobs in dustups with his bosses. His background, his rebellious streak and his empty wallet made him an anomaly in big-time amateur golf, a tony world where stockbrokers, insurance salesmen and the idle rich play.

Thomas competed in 10 U.S. Amateurs and five U.S. Amateur Public Links Championships. At the 1990 U.S. Amateur at Cherry Hills Country Club in Colorado, he played a second-round match against Phil Mickelson that became famous for an incident on the first hole: Mickelson conceded Thomas a 25-foot par putt before draining his own four-footer for birdie to win the hole. Mickelson went on to win the match 6 and 5.

What stuck with Thomas that day wasn’t Mickelson’s ballsiness, but his dedication. “You wouldn’t believe it,” he told Falco. “These guys are out there working on their games eight and nine hours a day!”

Later that year, Thomas was arrested at his home following a seven-month investigation by South Plainfield police, who seized 44 pounds of marijuana, drug paraphernalia and a revolver that had been stolen in a burglary. He reportedly pleaded guilty to some charges, was fined $1,860 and was given five years’ probation.

If Thomas’s game had a flaw, it was short putting. He suffered from the yips, a condition booze may have worsened. But a switch to a long putter in the early 1990s helped, and his play soared. The pinnacle came when Thomas won the 1993 U.S. Mid-Amateur, earning him an invitation to the Masters.

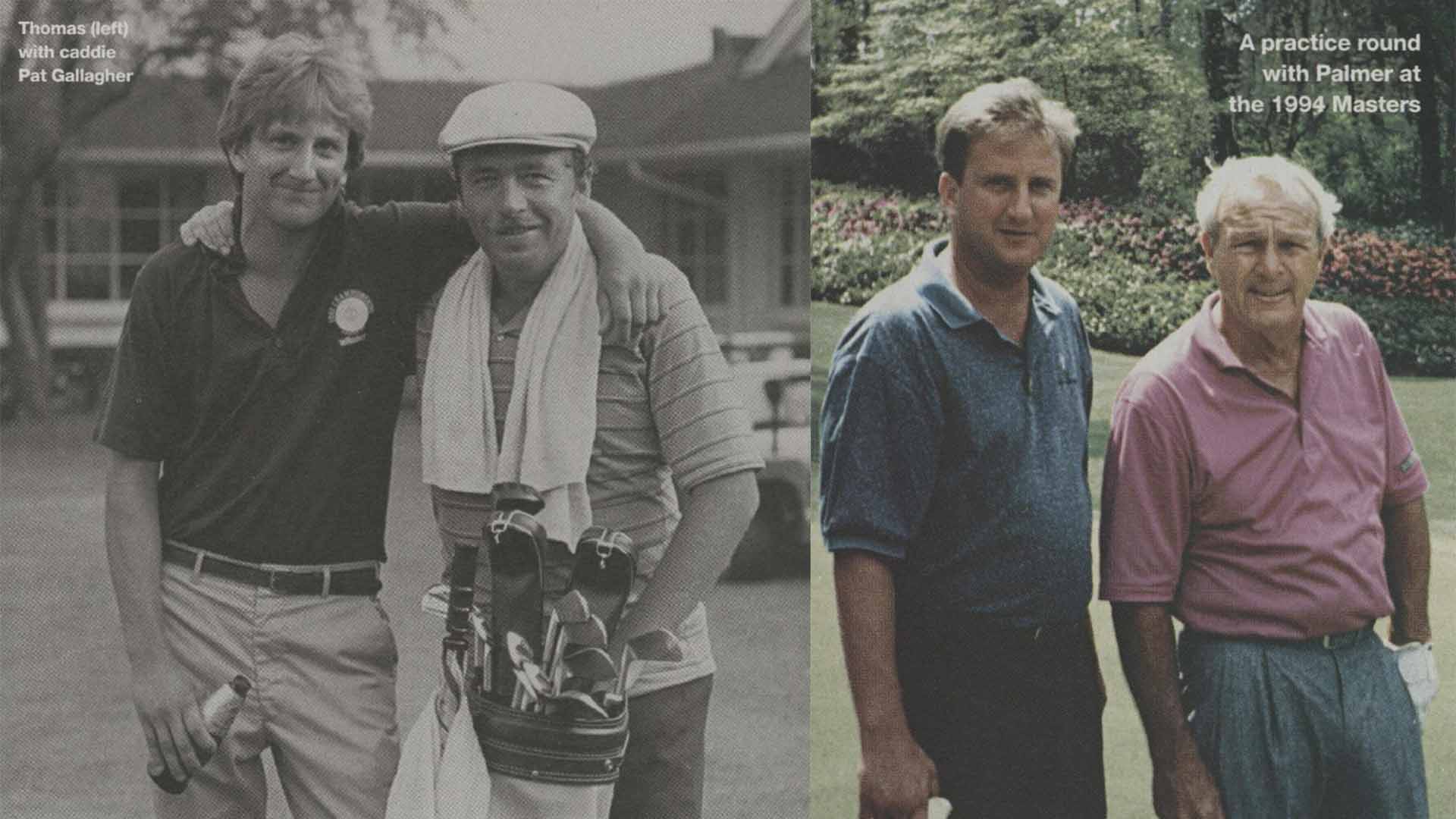

His 1994 appearance at Augusta was vintage Thomas, on and off the course. Before the tournament, in the bars of South Plainfield, he tried to auction off the right to be his caddie. When he got no bids, his high-school friend David Hodge nabbed the job by offering to pay Thomas’s airfare to Georgia and back. “For me, it was the dream of a lifetime,” Hodge says. “At the same time, I knew Jeff. I knew I was in for an eventful time.” Thomas treated his dream trip with a mix of respect and irreverence. During a practice round with Arnold Palmer, he stared in awestruck admiration at the King’s every shot. Before Wednesday’s par-3 tournament, Thomas was so nervous that he slipped off to the bathroom and missed his starting time.

Fortunately for him, his playing partners Craig Stadler and Jerry Pate waited while the next threesome played through. Thomas told friends that Augusta was the summit of his golf career. But it wasn’t all a bed of azaleas. On the practice tee one morning, he quarreled with a tournament official over a golf bag he’d gotten from an equipment maker. The official said amateurs weren’t allowed to brandish corporate logos. Thomas told him off before grudgingly switching to a plain bag. In Thursday’s opening round, Thomas shot a nervous 78 but got up and down from everywhere, including a par from behind the green on the sloping par-3 4th that Hodge describes as “completely absurd.” Even more absurd was what had transpired two nights earlier: Thomas met a woman at a post-round party and brought her back to the Crow’s Nest, a no-no in the clubhouse rooms where Masters amateurs stay. Whatever happened that evening ended with the woman storming out. A security guard phoned Thomas, who growled, “She’s your problem now.”

Rumors said he was booted from the Crow’s Nest and banned from future Masters; Augusta officials deny both. What’s certain is that he missed the cut with another 78 on Friday, a score that might have been lower if not for a slip-up between the 12th and 13th holes. After putting out on the famous par-3 12th, Thomas cut through the woods to the 13th tee, where he placed his putter on a bench. Caddie Hodge, who had been busy raking a bunker, didn’t notice the missing club until Thomas knocked a 2-iron onto the 13th green, leaving a 40-foot eagle putt.

“We’re walking to the green and Jeff says, “Where’s the putter?’” Hodge recalls. “At that point, the group behind us had teed off and we couldn’t get the club back without a penalty for slow play.” A frustrated Thomas four-putted for bogey with his 2-iron. He was still fuming on the next hole when a marshal returned his putter. “Jeff was pissed, I was upset, and we didn’t talk much the rest of the round,” Hodge says.

If Thomas had regrets about the Masters, they weren’t apparent at a post-tournament party his mother threw him. Around the barbecue grill in South Plainfield, beer in hand, he regaled guests with Augusta stories. Hanging in the backyard was a plastic tarp, the same makeshift backstop that Thomas had beaten countless golf balls into as a kid — a precursor to the pockmarked motel wall in Florida.

Even as his game was peaking, his life grew more strained. Alcohol and Thomas had never mixed well and now they mixed too often. He took a bartending job but was fired after a fight. When he was sober, friends saw the sweetness in him — here was a guy you could count on for a ride or for help with a home improvement project. But there was also a deep melancholy.

Sliding onto a barstool at the Polish National Home, a South Plainfield bar, Thomas would call out to anyone near the jukebox, “Put on something sad for me.” In 1996, Joan Thomas died, and the loss seemed to unhinge Jeff. His former fiancee, Vadala, attended the funeral and saw a kind but shattered soul.

“He was mourning, but he put his arm around me and said, ‘Carolyn, of all my girlfriends, she always liked you best,” Vadala says. “Jeff always wanted to make people feel good. He wanted to do the right thing, even if he didn’t manage to.”

After his mother’s death, Thomas began taking the antidepressant Trazodone. At a bar one night, he drank himself unconscious and had to be taken to a hospital to be revived. He won the 1996 Ike Championship, one of the MGA’s most prestigious titles, and just missed his second USGA title, losing in the final of the U.S. Amateur Public Links in Hawaii in a match tinged with controversy.

Trailing by four on the 15th hole of the 36-hole match, he asked his opponent, Tim Hogarth, to move his ballmark out of Thomas’s line. Thomas missed his par putt and Hogarth made his to go 5 up — except that he’d forgotten to return his mark to its original place. Thomas called him on the penalty and a flustered Hogarth lost the hole, and the next. Thomas wound up losing the match 8 and 7, but he was widely accused of gamesmanship, which friends say wasn’t his style.

“Jeff was a stickler for the rules,” Ansbro says. “His father had told him something that Jeff never forgot: ‘If you cheat in golf, you’re only cheating yourself.’”

Friends hoped golf would save him, but the game proved a false sanctuary. The course was a retreat from the chaos of his life, an orderly escape with rigid rules. But it wasn’t a place where he faced down his demons. It was a place where no one asked him to grow up.

A hundred times he seemed to hit bottom. But golf was always there, the siren song of his nonconformist lifestyle, holding out the promise of something more. Why be a bartender or a construction worker when he was always this close to being a champion? Why settle for a mere job—the choice most men must make when they grow up — when there was always the chance he might get himself together and be a star?

“In a sense, golf was his biggest addiction,” says Falco. “Jeff didn’t care about money. He was an unconventional guy, and he structured his life around the game. His dream was to be this gypsy vagabond golfer.”

In 1997, Thomas moved to a house in Jensen Beach, Fla., that had been passed down to his mother from his grandfather. His brothers, Alan and Chris, gave him the property outright the following year, hoping he would use it as a base for a run at the PGA Tour. Instead Jeff began playing less. He sprouted a potbelly. His lower back ached, and pain pills became another addiction he couldn’t break.

His conscience also likely troubled him. Unbeknownst to most of his friends, Thomas had a son with a New Jersey girlfriend. He and the boy’s mother were together on-and-off when Thomas lived up north, but she soon learned that on-and-off was all it could ever be.

“Most people live their lives planning the future, but Jeff wasn’t like that,” says the boy’s mother, who asks not to be identified. “Jeff lived day to day. To me that was troubling, but he would just smile and say, ‘Everything’s going to be fine. I’m going to turn pro.’”

From his new Florida home, Thomas made halting attempts to forge a bond with his young son, who is now 7 years old. Thomas called. He sent letters. He invited mother and son to visit, and on one trip Thomas taught his son to play golf. The boy is a lefty, but Jeff made him swing right-handed — the better to draw power from a straight left arm.

“He was very patient with him, showing him the right grip and the right technique,” says the boy’s mother. “Jeff would be so proud — [my son] can now hit it more than 100 yards.”

Thomas kept a photo of his son in his wallet, but mother and child remained in New Jersey, and the longer Thomas stayed in Florida, the further his old ties weakened. His brother Alan sent holiday cards that went unanswered.

In 2001, Thomas sold the house in Jensen Beach for $48,000, well below its market value. After that, his brothers lost track of him. On the golf course one day, he told Paul Piccolo he was on his way to Reno, Nevada. “He had the money from his house in cash — half of it in his pocket, the other half in his golf bag,” Piccolo says. “I said, ‘Open an account, put some away for a rainy day.’ He said, ‘No, I’m going to Reno.’” Thomas went on a six-week gambling binge, hopping from one casino to another. After two weeks, he would tell Piccolo later, he’d tripled his money.

“T said, “Why didn’t you come home with it?’ ” Piccolo says. “But it was right after September 11 and he was worried about getting through airport security with all that cash. I said, ‘So why not buy a car and drive home?’ But Jeff was going to do what he was going to do.” ;

What he had done was return to the roulette and blackjack tables, where he went bust. Piccolo got a letter from Thomas. “He started off talking about this nice vacation he had,” Piccolo says. “Then at the end it said, ‘Please come visit me. I’m at the county jail.’”

Thomas was back in Florida, doing a three-month stint for a DUI. After his release, he settled in Hobe Sound, a city of extremes carved from the Florida wetlands, where tree shrouded private clubs abut trailer parks and last-chance motels. He took a room at the Heritage Inn, a motel along U.S. Route 1 with a swimming pool overgrown with weeds and a sign offering haven for $39 a day. He took a job as a caddie at McArthur, a new club whose founders included PGA Tour star Nick Price, business leader Wayne Huizenga and Miami Dolphins immortal Dan Marino.

“He called pretty frequently before we opened and mentioned how he’d played at Augusta and met Nick Price and all that,” says former McArthur caddie master Lenny Cooke, who hired Thomas. “A lot of guys will tell you stories. But Jeff turned out to be the real deal.” McArthur head pro Andrew Shuck knew the New Jersey star from his own amateur playing days, so he wasn’t surprised when Thomas shot par to win the caddie tournament. What surprised Shuck was that Thomas was willing to hump bags for other players when it should have been the other way around. “He never complained about work and was always professional,” Shuck says. “He was never resentful that things hadn’t turned out the way he’d hoped.”

Says fellow caddie Bobby Miller, “Jeff would talk a lot about his accomplishments — not bragging, just proud. One time this lady from New Jersey shows up, and when she finds out who he is she’s so excited.

He was carrying her bag, but she treated him like he was a celebrity.” Thomas no longer competed in top amateur tournaments. After failing to survive stroke-play qualifying in the 2000 Mid-Amateur he skipped the next two Mid-Ams despite his 10-year exemption. But his competitive fire wasn’t completely extinguished. One morning, Piccolo persuaded Thomas to join him in a skins game.

A Thomas birdie won the pair $350 and afterward, over a tall glass of straight vodka in the clubhouse, he said, “Me and you, Paulie, we’ll come back to take these guys again!” They never did. By spring 2003 Thomas’s swing was the same old inside-out sweep, but his hands shook so much he had trouble chipping. He was short on cash — instead of buying new shoes to match the other caddies, he colored his old ones black with a magic marker — but never asked for handouts. No one at McArthur sensed the depth of his spiral. His old friends hadn’t heard from Thomas in years. “The last time I saw him, it was as if his soul had been abducted by aliens,” says his former fiancee, Vadala. “When he told me he wasn’t playing much golf, I knew something inside him had died.”

The summer of 2003 came to Hobe Sound, sweltering as always. On a good day in peak season, a McArthur caddie could make $300. Now Jeff showed up every morning at the caddie shack, looking for loops that weren’t there. Few members visited McArthur; most of the caddies headed north in search of steady work.

But Thomas and Bobby Miller stayed. To fill the idle hours, Miller would drop by Thomas’s place to watch SportsCenter or shoot the breeze over beer. There, in the living room, Thomas would put on impromptu clinics, flushing 3-irons off the carpet into the back of his couch.

“Some of his shots would miss and hit the walls, but most went right where he was aiming,” Miller says. “The guy was so good he could have swung inside a phone booth. He never let on that he was in trouble. I wish I had known. Maybe he just felt he no longer had the right to ask for help.”

Late July. Thomas hadn’t shown up at McArthur for days. The club staff called the Heritage Inn and reached assistant manager Esmail. When she opened the door to room 234, she found golf balls strewn around the floor. A case of beer sat in the fridge. Near the kitchen doorway were two barstools, and a drawer and overturned coffee table formed a funnel for practice putting. On a table sat a dog-eared copy of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, plus a stack of music tapes and a wallet with an expired handicap card from the New Jersey State Golf Association, with hardly a score over 68. And in the bedroom, splayed naked on his back across the bed, lay Jeff Thomas, his body badly decomposed. Police found empty prescription bottles in his bathroom — painkillers, sleep aids, antidepressants — but an autopsy showed no signs of overdose. The coroner said he had died of a seizure or heart attack. The official cause of death: alcoholism.

It took almost four w eeks to track down his bro thers. Alan held a small service for Jeff in New Jersey, in the same cemetery where their parents are buried, behind the 7th hole of Plainfield West. Some of Thomas’s ashes were scattered there; the rest were sprinkled on the course’s practice green.

In the caddie shack at McArthur Golf Club, Bobby Miller hung Thomas’s sweat-stained caddie hat on the wall in tribute to his friend. Miller had known Thomas for only a short time, as a fellow looper and a drinking buddy, but long enough to get a glimpse of his fatal flaw: Sad, gifted Jeff Thomas was too damn good at golf. Not a talent like the greats — Tiger or Mickelson — but a talent on the next level down, where you’re too good to give up but not quite good or driven or disciplined enough to reconcile what you want to be with what you are. And so you’re not quite Mickelson and your e not quite a nobody. You’re just a sad, broke, medicated middle-aged man hitting iron shots at the walls of a tumbledown motel.

In the end, his talent may have been his downfall. If he hadn’t been so good at golf, he might have been forced to find a real job — a real life — when he still had the chance. “After he died, I went to the bar where Jeff and I used to hang out,” Miller says. “And I said to the bartender, ‘Saddest thing is, Jeff should have gone on to other things. When you think about it, we should never even have known the guy.’”