2024 Wyndham Championship: How to watch, TV coverage, streaming info, tee times

2024 Wyndham Championship: How to watch, TV coverage, streaming info, tee times

A master plan: Exclusive look inside the days that led to Tiger Woods’ 2019 Masters victory

This is an excerpt adapted from GOLF senior writer Michael Bamberger’s new book, The Second Life of Tiger Woods. To learn more about Bamberger’s book, click here, and to buy it, click here.

Tiger Woods started talking about the importance of taking “baby steps” even before he won his first Masters, in 1997 by 12 shots when he was 21. He was lifting from the Earl Woods playbook. Improvement is incremental. It requires time and effort. You gotta walk before you can run.

In 2017, Tiger’s back was so bad that not only did he sit out the Masters for the second consecutive year, he told Gary Player at the Champions Dinner that his days as a competitive golfer were likely over. But one year and one spinal-fusion surgery later, he played his 21st Masters.

At that 2018 Masters, parts of his game were good and parts were works in progress. He had moved beyond baby steps, but he was riding a bike with training wheels. He finished in a tie for 32nd.

The good news for Tiger, by the end of that week, was that he knew what he had to do. He wasn’t happy with his driving game. He wasn’t happy with some of his equipment specs. He wasn’t happy with his strength and stamina. Tiger Woods with a list of things he’s unhappy about is a happy man. He lives for what it takes.

By April 2019, he liked the 14 clubs in his bag, right down to their shafts. (Critical.) He liked his driving game. He was stronger and fitter. A window was open. He could see that. When you’re 21, you think that window will stay open forever. When you’re 43, you know better.

SUNDAY, APRIL 7, 2019, MID-AFTERNOON

Tiger arrived for the 2019 Masters on the Sunday before Masters Sunday. It had been at least a decade since he’d arrived that early. On that occasion, a reporter asked Woods why he came when he did and Woods said, “So I don’t get bothered by people like you.” Tiger in his prime could do cold like nobody’s business.

He arrived early, and he arrived without an instructor. No instructor alongside him, and none would be coming. No Butch Harmon, no Hank Haney, no Sean Foley. It would have been unimaginable for Hogan or Palmer or Nicklaus to show up at Augusta with an instructor. But from the Greg Norman-Nick Faldo era and on, bringing your teacher had become common practice for elite players, Tiger among them. Tiger was going old-school.

Tiger was the clear captain of a golf team that had two other members, Joe LaCava, his caddie, and Rob McNamara, his on-the-payroll wingman. It was that threesome that decided to arrive on the Sunday before Masters Sunday. That might not sound like a big deal, finding one extra day. For Tiger, it is. He leads a crowded life.

He has two kids in middle school, who shuttle between his house and their mother’s. He has a restaurant and a course-design business. He has a yacht, an estate, a plane (the rich man’s big three) and a small battalion of employees to keep it all going. Woods is the CEO of a for-profit company and a nonprofit charitable foundation. Each requires meetings, phone calls, on-site visits. He’s the host of a PGA Tour event and an off-season event. He owes days to the companies that sponsor him. He was the captain of the U.S. Presidents Cup team. He’s busy.

But Tiger arrived at Augusta on the Sunday before knowing he could get himself in a golf cocoon. What a relief for him. For the week, Tiger had only three obligations. His annual Tuesday-afternoon press conference. The annual Tuesday-night Champions Dinner. And the Golf Writers Association dinner on Wednesday night, where he would receive the Ben Hogan Award for continuing “to be active in golf despite a physical handicap or serious illness.” He was doing that, all right.

He had a clear calendar and a warm weather forecast, the former good for his mind, the latter good for his back. He had four days to get himself ready for four days that could change the narrative of his life.

He arrived at the club on this Sunday afternoon with a plan to walk the front nine, using only a putter and a couple of wedges. Joe carried the full bag, and Tiger and Rob, a good player himself, talked about all manner of shots, long and short and in between. But this wasn’t a practice round. Tiger wasn’t practicing. He was communing. It was leisurely.

In time, they arrived at the par-3 6th. They looked at the green from the tee and then Tiger walked to the back right of the green, where the hole is typically located on Masters Sunday. They walked past Terry Holt, a slender Englishman and Bernhard Langer’s caddie, who just then was rolling balls on the green’s front left.

Terry figured Tiger and Joe and Rob would do their thing, get ahead of him and then he’d continue his own course walk behind them. Tiger did some putting and some chipping, as Terry expected. What Tiger did next he never could have unexpected.

Tiger walked down the green’s slope toward the veteran caddie, extended his hand and said, “Hi, Terry. How’s it going?”

Terry had had no interaction with Tiger since the second round of the 2001 Buick Classic in Westchester, N.Y. Terry was caddying for Paul Azinger, who had played with Tiger in the first two rounds. Terry had talked to Tiger about Tiger’s fishing trips with Mark O’Meara, some down-the-fairway small talk started by Terry. Now Tiger was initiating a conversation and calling Terry by name.

They shook hands and Tiger said, “I heard that this is it, that Bernie’s playing in his last Masters this year.”

Bernie. Terry was amused. Tiger loves to add a vowel to a given name whenever he can. (But he calls Rickie Fowler Rick.) But Terry was surprised, too.

“Really,” he said. “I haven’t heard that.”

Langer, who was 61, is the poster child for the golfing benefits, and the general benefits, of diet and exercise. Except for the lines on his face, Langer seemed to have barely aged since his second Masters win, in 1993. He continued to be one of the best players on the Champions Tour.

Tiger didn’t seem to be in a rush to go anywhere, and that made an impression on Terry. Over the years, Tiger has often looked like a man afraid to stop, worried that a crowd would form around him if he did, holding him prisoner while asking questions about his favorite courses in Arizona and forcing him to smile for phone snaps.

“Bernhard retiring, that would surprise me,” Terry said.

He could see that Tiger was listening, so he went on. In 2016, he noted, Langer had been two shots out of the lead through 54 holes.

Tiger surely knew, even though he wasn’t playing that year. If golf is on TV, he watches, typically with the volume off.

“Then last year we made the cut,” Terry said. In 2018 Bernhard finished only two shots behind Tiger, despite spotting Tiger 18 years.

Terry and Tiger talked about the Masters tradition by which former winners could continue to play in the tournament until the player decided he could no longer play to his standards, to use a Hogan phrase. (Hogan once said, “I am the sole judge of my own standards.”) In 1967, at 54, Hogan finished in a tie for 10th and never played in the tournament again. Other former champions have played into their 70s, shooting scores far higher than their age. It’s a sensitive subject at the tournament, for the club chairman and for the former winners who are in their 60s and 70s.

For Terry, 60 himself then, it was interesting to realize how attuned Tiger, at 43, was to the issue. But in the year Tiger won his first Masters, Arnold shot 89-87 to miss the cut by 27 shots.

They agreed that the course, now more than ever, had a way of telling a player when it was time to call it a day. When Tiger first started playing in the Masters, the course was much shorter and wider.

“But there are certain years when veteran players can still contend on this course, because they know how to play it,” Terry said.

“I would agree with that,” Tiger said.

A firm, fast course is more playable for more players. But 2019 would not be such a year, they both knew, as the course was playing long and slow after a soaking winter and spring in Augusta. Even with all the underground apparatus — there’s a SubAir system to drain the course — it would play soft. Suddenly, they were two golf nerds comparing notes.

“I think some of these players retire too early,” Terry said. “Look at what your friend Mark O’Meara did just last month.”

After missing the cut at the 2018 Masters, O’Meara had decided to call it a day. No more Masters. But then he started playing better, and in March 2019, at age 62, he won on the Champions tour. That win made him the fourth-oldest winner ever on that tour.

“I saw that,” Woods said. He knew about O’Meara’s win in the three-round Cologuard Classic, held in Tucson, and about the eight consecutive birdies O’Meara had made. Tiger will meet the age requirement for the 2026 Cologuard Classic, if the event still exists.

Terry was wearing the heavy white overalls that the club requires caddies to wear. Tiger had his putter in hand. Joe and Rob were at the back of the green. Before long, Tiger went back to work, and Terry did, too.

The whole conversation might have been three minutes. But it was memorable for Terry. He had never seen Tiger so personable, so relaxed, so warm. Tiger continued to seven, and Terry followed him. Tiger and Joe and Rob walked eight, they walked nine. They took their time on the 9th green. It was 6:40 but there was still light in the sky. They called it a day.

MONDAY, APRIL 8, 2019, 8 A.M.

On Monday morning, Tiger picked up where he left off, but now he was ready to play, to use all of his clubs. At eight o’clock, Tiger stood on Augusta’s 10th tee beside two of his favorite people in golf: Justin Thomas, who was 25, and Fred Couples, who was 59. Two months earlier, Tiger had named Fred an assistant captain for his Presidents Cup team, which would play in Australia at the end of the year.

ADVERTISEMENT

For pure natural talent, Fred, along with John Daly, is probably as gifted as anyone who has ever played, yet he won only one major title in his career — the 1992 Masters, with Joe LaCava caddying for him. And he might not have won that one had it not been for the improbable way his ball stayed on the sloping bank that separates the 12th green from Rae’s Creek. He made par there, pitching it stone dead from the bank with exquisite nonchalance and bare, tanned hands.

His next move is part of the legend of Fred: He fished out a drowned ball from the creek in one easy gesture. Even though he was playing in the last group on Sunday at the Masters, he was at heart a public-course golfer, and he couldn’t just walk away from a free ball staring him in the face. It’s almost impossible to imagine Tiger doing anything like that. Lost in the telling are the five practice swings Fred made, four of them carefully made outside the yellow hazard line. Fred only made it look easy in the end. It wasn’t.

Tiger had won way more often than Fred, and often by ridiculous margins, but somehow Tiger’s wins, and his life, never looked easy. For Fred, it was the opposite. Nonchalance was his art form. They’re an odd couple, Fred and Tiger.

“I’m not trying to be mean, but Tiger isn’t as helpful as Freddie,” Justin Thomas said after those nine holes on Monday. He wasn’t being mean; he was being truthful. Whatever Justin got from Fred, he’ll likely remember it forever. Tiger was once Justin, a sponge, soaking up whatever he could from Greg Norman and Nick Price, from Seve Ballesteros and José María Olazábal, from Arnold and Jack. But pay it forward is not really his thing, not when the chips are down and the wheel is spinning. Tiger Woods didn’t come to Augusta to help Justin Thomas play Augusta National better. To Tiger, Justin was one more guy he had to beat. Why would he possibly want to help him?

TUESDAY NIGHT, APRIL 9, 2019, SEVENISH

Tiger parked his tournament Mercedes courtesy car (he’s not a valet guy) and entered the clubhouse for the Champions Dinner. He was right on time, as per usual. His gait was slightly pigeon-toed, different than it was when he was a kid starting out, before his surgery count started mounting. He had on pressed pants and a pressed shirt, a knotted tie, no coat. His club blazer was sitting in his locker, which he shares with Jackie Burke. Tiger likes to travel light.

Everybody eats at one long rectangular table. There’s no assigned seating, not even for the winner, but guys tend to sit in the same spot each year, with allowances for new arrivals and RIP departures. After Arnold died, Tom Watson moved beside Nicklaus. Tiger sits to Jack’s left. Mark O’Meara sits next to Tiger.

Down the table from Woods and O’Meara is the praise-the-Lord, pass-the-biscuits section, where Bernhard Langer, Larry Mize and Zach Johnson sit together. Olazábal sits near some of the other European players. Woods is across the table from him on a diagonal.

Tiger is a fast, head-down eater, and he’s never been one to linger at these dinners, even in the best of times. At the 2017 dinner, he was so uncomfortable that he could barely sit, and he was out the door early. He had a plane waiting for him, not that anybody knew. But at the 2019 dinner, hosted by Patrick Reed, Tiger didn’t seem to be in any rush at all. The main course was bone-in cowboy rib eye. Good choice, Pat. Tiger served cheeseburgers one year, steak fajitas another, porterhouse steaks twice. He was enjoying himself. What a difference two years can make. He was old at 41 and reborn at 43.

When Jack was 40, he won the U.S. Open and the PGA Championship. At 41 and 42, he played in all eight majors and had five top-10 finishes. He was going strong. Tiger’s body in 2017, at 41, was crying uncle. He was in pain when he told Gary Player he was done. When Player told Nicklaus what Tiger had said, sorrow washed over Big Jack. Nicklaus wanted to keep his records, of course: the only player with six green coats, the only player with 18 majors. But he also wanted Tiger to have the chance to go down swinging.

Tiger flew off for a medical consultation that night. Nobody could have possibly predicted what would happen in the next 12 months, and then in the 12 months that followed that year. But as Jack Nicklaus has said more than once, “Nothing Tiger does surprises me.”

In late April 2017, two weeks after that dismal Champions Dinner, Woods had spinal-fusion surgery with a specialist, Richard Guyer, at the Texas Back Institute. It’s the kind of procedure after which some patients get some relief, so Guyer wasn’t promising, and Woods wasn’t expecting, a miracle. He was looking to play backyard soccer with his kids again. If it all went well, maybe he could at least be a recreational golfer again.

Things got much worse before they got better. One month after the surgery, on Memorial Day, in the middle of the night, police in Jupiter, Fla., found Tiger on the side of the road, sleeping in his $200,000 Mercedes. He was practically in a comatose state, and he was lucky nobody died that night. Woods was arrested on a DUI charge, and a blood test revealed five different drugs in his system. He went to a rehab facility, pleaded guilty to a lesser charge and made a public vow to improve his health in every way. For the rest of 2017, his public outings were few. But all the while, he was making incremental improvements in his life. At the end of 2017, he turned 42.

In 2018, he played a true full schedule for the first time since 2013. In 2018, he played tournament golf without a swing coach for the first time in his life. There was an excitement from him and about him that was unprecedented. Woods contended at the Valspar tournament in Tampa in March. The next month, at the 2018 Masters, he was almost ebullient—he was playing tournament golf again. In July he contended in the British Open, and played the fourth round with the eventual winner, Francesco Molinari. In August, Woods placed second at the PGA Championship, in sauna-like conditions at Bellerive, and hung around to congratulate the winner, Brooks Koepka. (That was different!) Then came the Tour Championship at East Lake in Atlanta. Tiger won for the first time since 2013. The level of hysteria brought to mind another Tiger win in Georgia—his 1997 Masters win.

At the end of 2018 he, of course, had another birthday. He turned 43 and seemed far younger than he did at 41. In 2019, he picked up where he left off. A full schedule in January, February and March. He improved his putting, his driving, his strength, his stamina. Anyone could see that he had a level of openness and comfort with reporters, fans, tournament officials and other players that he had never shown before.

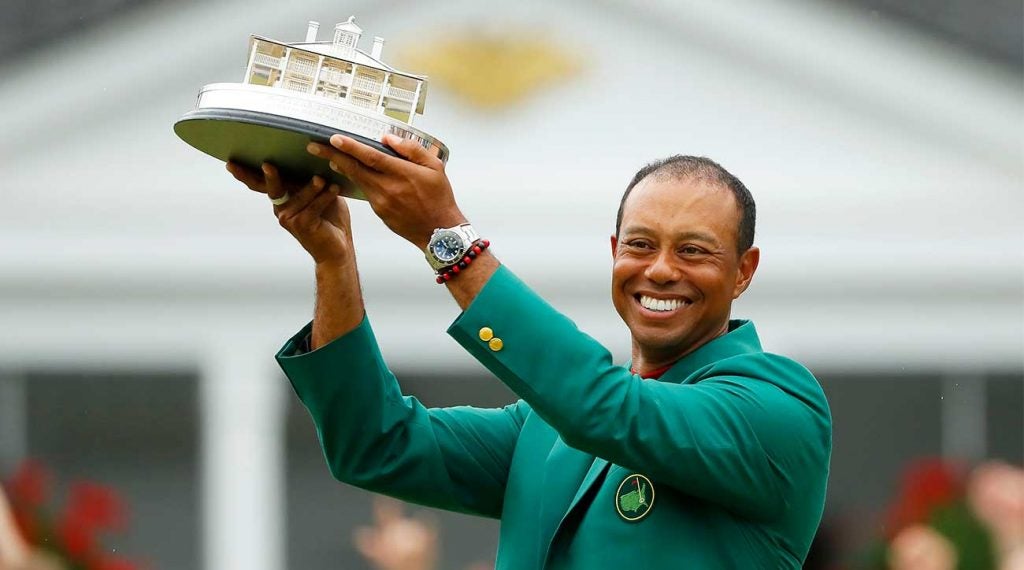

Then came the Masters. The 2019 Masters. The Sunday arrival. The nine holes with Justin Thomas and Fred Couples on Monday morning. And now he was back at the Tuesday-night Champions Dinner, seated beside Jack, right on schedule, in their customary seats. Jack was struck by how positive Tiger was, how confident. “Almost, almost cocky,” Jack said later. “And I have never seen him cocky.”

“You’re swinging so well,” Gary Player said on that Tuesday night. He’s prone to hyperbole, but Tiger knew those words were true.

“I’m not finished yet,” he said.

WEDNESDAY, APRIL 10, 2019, LATE MORNING

Tiger saw Olazábal again late Wednesday morning, when each gave the other an impromptu master class on how to pitch a golf ball. Not just how to pitch a golf ball but how to do so at Augusta National, which is slightly different than pitching a golf ball anywhere else, because the Augusta turf in mid-April is tight and grainy, and the Augusta fairways, and especially the greens, have so much slope and movement in them. Also, those pitch shots sometimes have to carry wide, deep bunkers with raised lips.

As an amateur on the cusp of prodom, Tiger was greedy. He wanted John Daly’s length and Fred Funk’s accuracy. He wanted Davis Love’s long-iron game and Jeff Sluman’s bunker game. And he wanted Olazábal’s pitching, chipping and putting game, which he ranked ahead of even Phil Mickelson’s. Once, while waiting on a tee at Torrey Pines, Tiger said, “Phil can do more spectacular stuff, but day in and day out, he can’t hold a candle to Ollie.”

On Wednesday morning, Tiger was watching Olazábal, older by a decade, play pitch shots in the short-game area on the clubhouse side of the tournament range. It consists of several greens and bunkers surrounded by a half-acre of perfect turf. The conditions mimic exactly what the players find on the course.

Olazábal pitched one exquisitely. Tiger watched and said, “I don’t think I have that shot, Ollie.”

“Don’t try to bulls— me, Tiger — I know who you are. You’ve got every kind of shot.”

Tiger responded by dropping a ball from the spot where Olazábal had just played and practically holing the shot. Olazábal’s nod said it all. Of course.

They then spent 20 minutes talking shop. They talked about how pitch shots and chip shots at Augusta are different than they are anywhere else in the world. They discussed how sticky and grainy and tight the fairway turf is at Augusta. How you seldom get a level lie. How the grain is typically against the player. How the margin for error is zero. They talked about ball position, about the steepness of the downswing, about holding off the follow-through. They talked about how you have to read the grain twice at Augusta when playing a pitch shot — once at address, a second time where the ball will make landfall. They talked about wedges: their leading edge, their bounce, their scoring lines. There on the range were two of the best wedge players ever. Two magicians, each performing for the other, unaware that they were drawing a crowd.

THURSDAY, APRIL 11, 2019, 11:04 A.M.

In the first round, Tiger stood on the first tee with Jon Rahm of Spain and Haotong Li of China. The day was unusually warm. Tiger played first, an honor given to each Masters champion in each threesome on Thursday. Tiger stood on that tee with a driver. The perimeter of the tee box was thick with humanity. There have been many first tee shots over the years that were a disaster for Tiger. Not this one. He ripped one right down the middle. He couldn’t know what the next 75 hours would bring. What Tiger knew was that he had done the work, and that he was ready for whatever came his way.

This piece was adapted from The Second Life of Tiger Woods, by Michael Bamberger. Published by arrangement with Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster. Copyright 2020. Available March 31 wherever books are sold.

To receive GOLF’s all-new newsletters, subscribe for free here.

ADVERTISEMENT