The only Masters story Jim Nantz won’t tell

The only Masters story Jim Nantz won’t tell

Here’s what it’s like to play golf with USGA chief Mike Davis (hint: yes, he’s a rules stickler, but only sort of)

PEBBLE BEACH, Calif. — Philosophical question: If the head of the United States Golf Association knocks his ball into a hazard and no one finds it, does he cut himself some slack and take a free drop?

Not if he’s Mike Davis. Not even when he’s playing a hit-and-giggle round.

It’s a blustery afternoon at Pebble Beach Golf Links, whitecaps foaming on Monterey Bay, and Davis’s approach on the par-4 10th hole has vanished into fescue on a red-stake-bordered bluff along the right side of the fairway.

Under recently revised Rule 18.2, Davis has three minutes to conduct a search, but this is ankle-sprain terrain and a hopeless, grassy tangle, so he calls off the hunt, finds his point of relief and drops a ball from knee-height, abiding by another newly revamped rule that is not so tough to follow, no matter what some Twitter-ranting Tour pros claim.

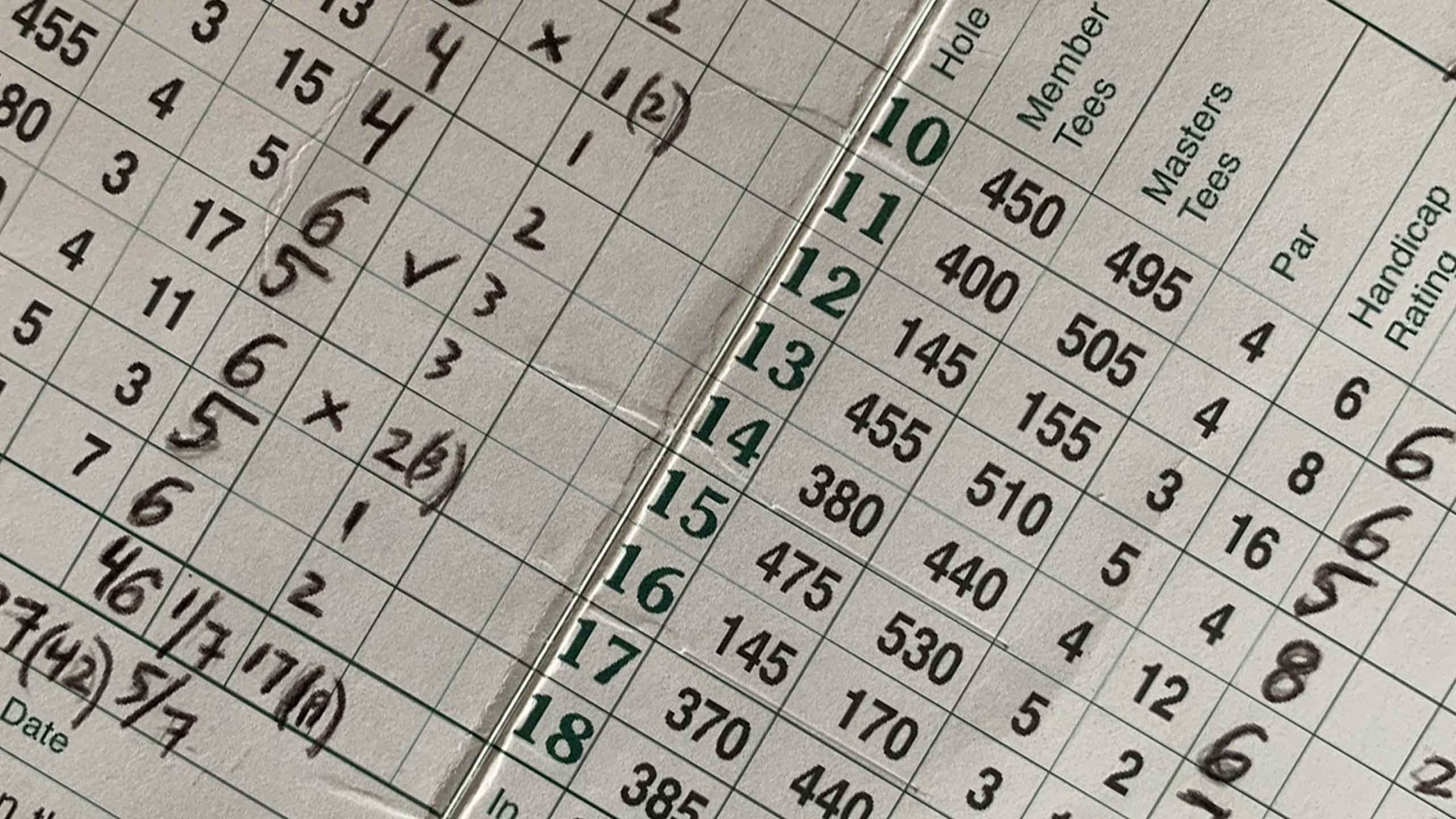

Playing his fourth, Davis stuffs a wedge for a good look at bogey. No one else is keeping individual scores in this shotgun outing, but it’s in his DNA to keep a mental tally.

“On a day like this, if other people want to bend the rules a bit, I’ve got no problem with it,” Davis says. “This is just the way I play.”

At 55, dressed in a palette of restrained blues and grays (what, you were expecting Loudmouth pants?), Davis looks relaxed and happy, and why not? This round is a bonus, a break from the grind: a casual affair tacked to the end of a scouting mission in preparation for the 119th U.S. Open, which kicks off June 13 at Pebble Beach.

It’s the sixth time the course will host the event, and the first time since 2005 that Davis won’t be in charge of the U.S. Open setup. He remains involved, however, in what he insists is a team effort.

“It’s never been about one person,” he says. “Even if it’s often been perceived that way.”

As with any U.S. Open, there are endless course-related details to attend to. This year, though, as the championship returns to a tried-and-trusted venue, following a string of controversy-soured installments, there’s an added weight of import, a growing sense of portent. And extra pressure to get it right.

A guy might as well try to have some fun.

“I was going to fly home last night,” says Davis, who lives in New Jersey, near USGA headquarters. “But then I thought, ‘That’s crazy. Who would pass on a round at Pebble Beach?”

Like many before him, Davis has learned, after 30 years at the USGA, that the best way to develop a rusty golf swing is to land a job in golf administration. He plays about 15 times a year. Still, a rusty swing for Davis is a tidy swing for most. Raised in Pennsylvania, he won the junior state championship in 1982, etching his name on the trophy alongside Arnold Palmer’s, and lettered in golf at Georgia Southern University, on a team with future Tour winners Gene Sauers and Jodie Mudd. Last he checked, his index was 4.1. At that number, you wouldn’t want to play him in a money match.

On this day, in deference to his partners, Davis is pegging it from the white tees, a challenge he guesstimates to be some 20 shots easier than the U.S. Open setup. Starting in the shotgun on the 2nd hole, Davis blocks his opening drive but declines a mulligan, a habit he ascribes to a conversation with his cross-Atlantic counterpart, Peter Dawson, the former head of the R&A.

“Peter once asked me, ‘What is it with you Americans and your mulligans?’” Davis says. “His argument was that it’s very often the hardest shot of the day and you’re giving yourself a free second go at it? That got me thinking.”

In a casual round, he says, he’d never chide a partner for a breakfast ball. But it’s not the kind of a leeway he allows himself.

Come the U.S. Open, Pebble’s 2nd will play as a par-4. Today, though, it’s a par-5. Davis escapes without dropping a shot and quickly settles into an enviable groove. Pars on Nos. 3 and 4. Birdie on 5. Par on 6. Birdie on 7. A striped long iron down the center of the 8th, an arresting par-4 with an Evel Knievel second shot across a gorge.

“Good thing you laid that back a little,” his caddie says. “They’ve got the rough shaved down at the end of the fairway so everything just runs out over the cliff.”

“Wonder who did that?” Davis deadpans.

ADVERTISEMENT

Along the edge of the fairways, it’s another story: the rough is up. Not quite wedge-out-sideways high but about half as long as it will be a few weeks from now. The greens will also be firmer and faster, though the setup team will have to keep close watch.

“These greens are so small,” Davis says. “You don’t want them so firm that players can’t hold them.”

You also have to guard against outlier conditions, as in the final round in ’92, when Tom Kite won at Pebble in a near-tempest. The average score that day was 77.3.

As he makes the turn, Davis is one-over. But not for long. A shot just past his target on the slick 11th green leads to a three-putt.

“I know better than to leave that putt above the pin there,” Davis says, sounding not mad, just matter-of-fact.

Having played some 75 rounds at Pebble, Davis knows the other greens intimately, too. As he goes about his day, he points out changes to them that hold implications for the world’s best players, including renovations to the 9th, 13th and 14th greens that have broadened the options for pin positions. A newly freed up patch on the back-right of 13 should prove to be particularly demanding fun.

Davis notes other features, like long native grasses rimming many bunkers, flattering eyelashes that will need to be trimmed for the championship so balls don’t go missing in them.

Prepare all you want, someone is always going to find a problem, all the more so in an era when some golfers have adopted USGA-bashing as a second sport. Complaints in 2017 that Erin Hills was too player-friendly gave way to grousing the next year that certain holes at Shinnecock Hills were flat-out unfair.

Davis owns the errors he believes were made (the Saturday pin position on the 15th at Shinnecock that caused so much hair-pulling resulted from a “misapplication” of water; the controversial DJ penalty the year before at Oakmont was a “complicated ruling” further muddied by the spread of inaccurate information). But he’s also not inclined toward monkish self-flagellation. Nor does he get his back up, or engage in testy back-and-forth. He says he’d rather take the high road, so he mostly holds his tongue. He understands that catching flack comes with the gig.

“Think about Washington,” he says. “No matter the political persuasion, when was the last time you heard anyone say anything good about Washington? Even so, I think people understand that we need governance ― that without governance, you get chaos.”

His overriding hope is that this year’s setup does not become the story, that the U.S. Open spotlights the game’s best players, set against the grandeur of Pebble Beach. That’s not how it works at the AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am, when the course shares the stage with all sorts of stars.

Davis competed in the pro-am this past year, when soggy conditions allowed for the field to play lift-clean-and-place. Everybody did, except Davis.

“Everyone was playing within the rules that week,” Davis says. “It’s just that I like to play it as it lies.”

You can’t help wonder if he feels he has to do it: How would it look if the grand pooh-bah of the governing body was seen playing golf any other way?

Then again, rules-abiding doesn’t seem a burden to him. And, to his credit, he’s not a fuddy-duddy or a finger-wagger. You want to wipe away a putt or employ a foot-wedge? He won’t reprimand you if there’s nothing at stake. It’s not as if he has to protect the field.

Rather than tut-tut, he prefers to look for teachable moments.

“If I’m playing with someone who’s just learning and they’re in the bunker, I might take that opportunity to say, ‘You know, in that case, you’re really not supposed to ground your club,’” he says. “Or, ‘On the green, you’re really supposed to place your mark behind the ball, not in front of it.’”

He has no particular pet peeves, and finds it bemusing how certain things get under certain people’s skin. Americans, he notes, take special umbrage at non-conforming equipment, which is no more irksome to him than an improper drop.

“In the end,” he says, “a breach is a breach is a breach.”

The round winds down. Another stretch of pars, blemished only by a hooded iron on 16 that winds up in a hazard. Provisional. Bunker. Sand blast. One-putt. Double-bogey, carded in adherence to the letter of the law.

On the 1st hole, his last hole, Davis tugs his tee shot, yielding a nasty lie, wide left of the fairway. A few weed-whackers later, and he’s on the green, facing a five-footer that will net him double bogey and a six-over round of 77.

The wind is high. The sun is low.

“This is for the U.S. Open,” Davis says.

He jams it in the heart.

ADVERTISEMENT